Yes, We Can Solve Hawaii’s Housing Crisis

To solve homelessness, we need to build lots more affordable housing, but Hawaii has failed to do that for decades. Three men with very different visions are trying to fix that.

It’s an improbable place to build affordable housing: 14 acres of undeveloped waterfront, sandwiched between the grim industrial districts of Mapunapuna and Sand Island.

This small, unnamed peninsula forms a kind of delta where Maunalua and Kalihi streams empty into Keehi Lagoon. Tall, silky grasses grow over much of the interior. Mangroves line the shore. The sun glints on the slack waters of the lagoon where schools of young mullet flash back and forth in the shallows. If you squint, it’s almost beautiful.

There is already a homeless community occupying this state land along Keehi Lagoon. Many of the residents live in floating shacks or primitive homesteads in the brush. Photo: Aaron Yoshino.

But it’s also a wasteland. There’s no infrastructure: no power, no water, no sewer. Like most of the surrounding area, this tract is composed of reclaimed land – construction waste and dredging spoils from the lagoon. It’s best known for a pair of paintball courses that have been bulldozed into the scrub. A crude, gravel parking lot fronts Nimitz Highway, partly hidden from passing motorists by a massive row of trash from the homeless camp under the viaduct. Two pairs of concrete footbridges once linked the lonely peninsula with neighboring districts. On one side, the bridges are now gated and locked; on the other side, they dead-end into a chain-link fence behind a Sand Island construction yard. All of this makes development here a complicated process.

An Inspiration

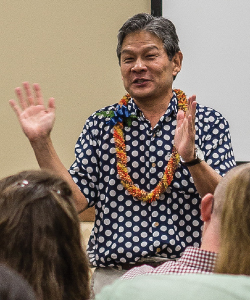

But, if local businessman Duane Kurisu has his way, this desolate tract of state-owned land will soon be the setting for Kahauiki, a new community offering mid- or long-term accommodation for dozens, maybe hundreds, of homeless families. There will be vegetable gardens and fruit trees, public restrooms and showers, and a plethora of social services.

In the business community, Kurisu is best known as a commercial real estate investor and part-owner of the San Francisco Giants baseball team. Through his holding company, aio, he also owns a variety of food, technology and media businesses, including Hawaii Business. He found the Keehi location when one of those companies, the local ESPN radio station, had to move its antenna to make room for rail, settling on a site near the paintball courts. Around the same time, Kurisu was considering how to help alleviate Hawaii’s homeless crisis. Naturally, he thought about the vacant land along Keehi Lagoon.

In the business community, Kurisu is best known as a commercial real estate investor and part-owner of the San Francisco Giants baseball team. Through his holding company, aio, he also owns a variety of food, technology and media businesses, including Hawaii Business. He found the Keehi location when one of those companies, the local ESPN radio station, had to move its antenna to make room for rail, settling on a site near the paintball courts. Around the same time, Kurisu was considering how to help alleviate Hawaii’s homeless crisis. Naturally, he thought about the vacant land along Keehi Lagoon.

The homeless population already knows about the property. A few dozen, mostly working poor, already live there, on little makeshift homesteads cleared from the brush, or on ingenious floating shacks moored to the mangroves along the shore. But Kurisu has something more ambitious in mind. Under the auspices of the aio Foundation, his nonprofit arm, he plans to build a plantation-style village here, with room for as many as 800 people.

Kurisu attributes his inspiration for Kahauiki to his plantation childhood on Hawaii Island.

“We lived in homes that were built by the plantation. It was a little bit like a homeless camp. The houses weren’t great and they were a little broken down. But, if it wasn’t for the plantation, we might have been in the same boat. In Hilo, I could hear people making fun of our family. Within our town, though, there was dignity. We shared things with each other. If you went fishing and caught three fish, you gave two away to your neighbors.”

That sense of community, of sharing and dignity, is what Kurisu wants to bring to Kahauiki.

“I think that, if this project doesn’t work, it will be because of government risk. If we cannot compress the time it takes to build the project, I don’t think it’s going to make it.”

—Duane Kurisu

His other inspiration for this project, he says, was a photo essay about homelessness in Honolulu magazine, a sister publication of Hawaii Business. “When I looked at that article, and thought about growing up in a plantation town, and I thought about all the hardships of the homeless, I thought that we, as aio, should step forward and take the initiative to build something where people could live with dignity.”

Never one to seek the spotlight, Kurisu spreads the credit for Kahauiki. First, he says, the aio Foundation isn’t just him; it’s all the people who work at aio companies. Maybe more to the point, the project has garnered support from others in the community. Nonprofits are sharing their advice and, if it is built, will deliver services to the homeless in the village. Local unions have offered to help with construction. Engineers and architects have volunteered their time and expertise. Other nonprofits are pledging financial support. There’s even the prospect of employment for some residents of the village. According to Kurisu, Vicky Cayetano, whose United Laundry facility on Sand Island is just across one of those footbridges from the property, has said she’ll give a job to anyone from the village who wants to work.

Karma may also play a role in building Kahauiki. The aio Foundation was one of the first local organizations to send support to Japan after the devastating 2011 tsunami. Now, that support may come full circle, Kurisu says.

“Komatsu, the big Japanese manufacturer, had built 5,000 of these modular homes for the victims of the tsunami. When they were no longer necessary, Komatsu was just going to toss them away. Instead, in February or March, we’re going to bring in some of these modular homes as a demonstration project.”

The advantage is that modular homes go up a lot faster than standard construction, and they’re more secure and comfortable than other temporary structures, like the containers used as homeless shelters elsewhere on Sand Island. Each of the Komatsu models, Kurisu says, includes two housing units, and they can be put up in about three days. More important, they’re cheap.

“It’s like 10 percent of what it would cost to build something,” he says.

All of this will help keep development costs low, which is critical for affordable-housing development, especially when you plan to keep rents below $500 a month, like those planned for Kahauiki. But these are mostly tactical issues. The trick to solving Hawaii’s affordable-housing crisis is to find strategies that will speed up development. That’s what makes Kahauiki so exciting, Kurisu says. It takes advantage of a wrinkle in state law to put the project on the fast track. But to fully appreciate this strategy, you first need to grasp just how complicated it normally is to build affordable housing.

The Standard Approach

Not surprisingly, the main impediment to building more affordable rental housing is money. This is especially true in Hawaii, where land costs so much. In fact, most affordable housing experts say such development is impossible unless the land is free. One solution is to use the zoning and entitlement process to require that developers dedicate a percentage of their market-priced projects to affordable housing. These “inclusionary rules” increase the stock of workforce housing. In booming Kakaako, for example, inclusionary rules have helped create a mixed-income community rather than just a wealthy enclave.

Stanford Carr, one of the pre-eminent affordable housing developers in the state, says inclusionary rules are pretty much the norm across the country. “If you didn’t have them, what would be the incentive for the government to grant rezoning requests?”

But, he notes, sometimes the rules can become too onerous.

“Back in the late 1980s, there was a time when they imposed a 60 percent inclusionary requirement. That was overreaching and eventually shut the door on affordable-housing development. The state realized that and changed the law to 30 percent.”

Developer Stanford Carr stands in front of Halekauwila Place, a 204-unit affordable rental project that he finished in Kakaako in 2014. Rents and other income were far too little to cover the cost of construction, so Carr made up the difference with federal and state tax credits and a loan from the Hawaii Community Development Agency. Photo: Aaron Yoshino

But inclusionary rules, even thoughtful ones, aren’t a cure-all. For example, in most instances, they simply shift development costs from the affordable units to the market-rate units. Bit by bit, they exacerbate the high cost of housing for the rest of us. Moreover, most developers build for-sale units rather than rentals. And, while we need more affordable for-sale units, they aren’t effective housing solutions for low-income people, who have no down payment and don’t make enough to cover mortgage payments. Most affordable-housing advocates say these people need rentals. But putting together the financing to build low-income rentals is a complicated game of three-card monty.

The vast majority of low-income rentals built in America are funded largely through a federal program called the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, or LIHTC (pronounced Lie Tech). Basically, the federal government issues tax credits to an affordable-housing developer, who sells them at a discount to companies that need a tax break. For most affordable developments, the proceeds from this sale make up the largest part of the equity in a project.

The residents of affordable housing “are county and state employees, small-business owners, visitor-industry employees, teachers and young professionals just getting started in their careers.”

—Stanford Carr

An example is Stanford Carr’s Halekauwila Place, a 204-unit affordable rental project in Kakaako that was completed in 2014. Carr walks us through the numbers:

“Halekauwila Place cost a total of $71 million to build. And that’s with zero land cost. This is the total development cost, including direct construction costs, architectural costs, engineering costs, entitlement costs, financing costs, bond costs, permits, sewer fees, water fees, parking structure, landscaping – the whole ball of wax. So, we were issued federal tax credits with a face value of $25 million, which we sold to a Mainland company for $23.5 million.”

In addition, he says, the state has a piggyback tax-credit program that matches the federal tax credits at 50 cents on the dollar. That added up to another $12.5 million in tax credits, which Carr sold to a local bank for about $5 million.

“So, the sale of the tax credits generated $28 million in equity,” he says. “But that wasn’t enough. It only represents 40 percent of the total development costs of the project.”

The next stage in the financing of an affordable rental development comes from a traditional mortgage. But there are complications.

“If you use the federal tax credit,” Carr says, “you’re limited to renting the units to households earning 60 percent of the area median income (AMI). For example, that’s a single guy who makes $41,000 a year. And the federal rules say he’s allowed to pay no more than 30 percent of his adjusted gross income toward his housing needs. That includes all his utilities. That’s the metric. So, if the guy is making $41,000 a year, he basically pays rent of $1,000 a month.”

In other words, an affordable rental property that qualifies for LIHTC has a legally limited income. The implications of this rule affect what kinds of projects can be financed.

“It backs into the mortgage you can support,” Carr says. “For Halekauwila Place, I could only borrow $25.8 million of long-term debt based on my cash flow. I have to rent the building out. I have to assume a 95 percent occupancy. I’ve got to put money away for replacement reserves, operating expenses, electricity, maintenance, management people, etc.”

If you’ve been following the math, you’ve noticed Carr is still about $17 million short of the $71 million he needed to finance Halekauwila Place. Carr calls the money required to cover this shortfall “gap funding.” Typically, Hawaii developers tap the state’s Rental Housing Revolving Fund (formerly the Rental Housing Trust Fund) for this gap funding, but the financing of Halekauwila Place followed the Great Recession, when these funds weren’t available. Instead, Carr says, “HCDA mirrored the Rental Housing Trust Fund and loaned me the $17 million. So, that all added up to the $71 million.”

It gets even more complicated. The gap funding needed to build affordable rentals varies with prevailing interest rates. When developers have to pay a higher mortgage rate, they need more gap funding. Carr is pushing the state Legislature to change one of the trust fund’s rules now so more affordable housing can be developed later.

The current rule caps the state’s Rental Housing Revolving Fund at $38 million. These funds are generated by the real estate conveyance tax, which is imposed whenever property is sold. Carr wants to eliminate the cap so the state can sock away money now, while the real estate market is hot. That way, when interest rates go up and the housing market cools, more gap funding will be available when needed.

“When times are good, we should bank the money,” Carr says. “Why are you capping it at $38 million a year? Let’s create the fund now. Today, it’s smart to leverage long-term debt while we’re in a low-interest environment.”

He also wants the state to alter its piggyback tax credit. Investors that buy the credits now have to spread them over 10 years; Carr wants to shorten that to five years. “If they pass this law, House Bill 2303, instead of selling the state tax credit for $5 million, as I did with Halekauwila, buyers might have been willing to pay me $10 million.” This extra $5 million would mean $5 million less in gap funding would have been needed to build the 204 low-income rental units at Halekauwila Place.

A Different Take

We talk about the state having an affordable-housing problem. But what if we have the formulation backward? What if we really have a wealth problem? That’s what developer Peter Savio thinks. He believes the focus on affordable rentals only makes the problem worse.

Before you discount his views, note that Savio is one of the largest affordable-housing developers in the state.

“I’ve done about 9,000 or 10,000 units of affordable housing in Hawaii,” he says. “Back in the 1980s and 1990s, I was also Hawaii’s biggest lease-to-fee converter, where I converted properties from leasehold to fee simple. I started as an affordable-condominium converter in the 1980s. That’s my real love: to get local people into housing.”

Savio has always taken a unique approach to affordable housing. “Basically,” he says, “I don’t sell at retail value; I sell at my cost plus a small profit. So, I could be selling someone a house at 50 percent of its appraised value. A house that’s worth $250,000, I might be selling at $120,000. Sometimes, it’s only 20 percent or 30 percent under market, but, whatever it is, it’s less than market value. Over the years, I’ve probably given away somewhere in the neighborhood of $300 million in potential profit. That’s just on that one activity. On other things I’ve done, I’ve probably given away another $500 million or $600 million in value.”

Savio is a disciple of the idea that home ownership creates wealth – especially for low-income people. He believes rent is a fool’s errand.

“Everyone in Hawaii is creating wealth,” he says. “You create wealth by paying your mortgage, and you create wealth by paying your rent. But the person who pays rent creates wealth for a landlord. The person who pays rent is giving away his family’s wealth to his landlord.”

The problem, Savio says, is that if you rent, you won’t be able to afford to live in Hawaii when you retire. That’s because, even if your income increases, so does your rent, so you can never save enough. You’ll never be able to afford the cost of living here when you’re no longer working and getting pay raises.

Peter Savio stands at Honolulu’s Pagoda Hotel; in the background is Rycroft Terrace, once part of the hotel, which Savio turned into 162 affordable housing units. The conversion helped fulfill Kamehameha Schools’ affordable housing requirements for its Kakaako development. Rycroft condos sold in 2014 for as low as $123,480 for a studio and as high as $274,990 for a two-bedroom apartment. Savio favors affordable-housing sales, not rentals. Photo: Aaron Yoshino

“But if you buy a property,” he says, “you lock in your monthly payment for 30 years. Your cost of housing doesn’t increase. Your wages do. Imagine what wages did over the last 30 years: They went from $400 a month to probably $4,000 a month. If you had bought a house in Hawaii Kai in the 1960s, your cost of housing would have stayed the same $250 a month even though rents went up to more like $2,000. So, the person who bought that house created a lot of wealth. If he saved that money, as he got pay raises, he probably bought a second, third or fourth property. Today, he’s a multimillionaire.”

Renting, Savio says, should only be a first step toward ownership. “You rent while you save money for your down payment, or get stability in your job, or whatever, so you can buy real estate.”

Rather than build more of the affordable rentals that traditional developers build, Savio advocates what he calls “equity-build” rentals. The idea is straightforward, if a little revolutionary. It would apply to any developer that uses government money to build affordable rentals. Basically, as tenants pay their rent and the owner pays the mortgage, any equity generated through the amortization of the loan goes to the tenants, not the owner. That equity is held in escrow for the tenants until they have enough money for a down payment on their own home. Then, they move out of the rental and the process begins for another tenant. In effect, the builder still owns the building, but his mortgage never goes away.

Savio believes that accumulating equity this way is the only way low-income people will ever become wealthy enough to buy a home. In addition to the equity, Savio says, he’d pass along any other government largess to the tenants. “If the government waives the sales tax, I’ll give that to them. If the government waives the property taxes, I’ll give that to them, too. The idea being: they rent, but they build equity. Then, in 10 years, they move out; they buy a property.”

But what’s in it for the developer?

“People say, ‘We’re going to build a whole bunch of rental units and fix the problem.’ Well, we’ve tried that. We tried it in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. When are we going to realize it doesn’t work?”

—Peter Savio

“He’s still making money,” Savio says, “just not as much.” For example, rents should be high enough to cover the owner’s expenses, plus a modest profit. The owner would also get all the appreciation and depreciation on the property. And, at the end of the affordability requirement – Savio says that should be 40 or 50 years – the owner can sell the property and get his money back.

This isn’t just an abstraction for Savio. He says he’s already trying to do it on a small scale with a 10-unit property. But he wants to scale up. In fact, when the City and County of Honolulu considered selling its affordable-housing properties a couple of years ago, Savio wanted to convert all of them to the equity-build program. He’s still interested in acquiring a large public housing project, like Kukui Gardens, to use as a pilot.

In addition to giving tenants their equity, Savio wants to prepare them for property ownership.

“If these people go through my program, it will be like an incubator, where I treat them like an owner. In effect, they’ll have a renters’ condominium. They’ll elect a board of directors. They’ll prepare the budgets. They’ll do the house rules violations. They’ll learn to be owners. Every month, they’ll get a statement that says, ‘You paid your rent, so you picked up $150 of equity.’ And every month, they’ll see their equity growing. We’ll even give them classes in real estate. After, say, 10 years, these people will think like owners. For the first time in their lives, they’ll have a substantial account.”

The Rebuttal

Savio knows most developers are skeptical about his plan. Even he acknowledges it’s a long-term solution to our affordable-housing crisis, not a short-term one. Even if it was wildly successful, it might take a generation before it impacted the chronic shortage of affordable housing; it doesn’t address the current shortage. According to the state’s most recent housing survey, Hawaii needs 26,000 more affordable rental units. Current programs only produce a few hundred a year.

The immediate need for rentals is a point that affordable housing advocates emphasize. Stanford Carr uses the example of renters at Halekauwila Place.

“These people are county and state employees, small-business owners, visitor-industry employees, teachers and young professionals just getting started in their careers. As they get promoted and their earning power gets stronger, those low rents will enable them to save money for a down payment and eventually buy a home. That’s why it’s important to build rentals, unlike what Savio says. Because we all start as renters. You’ve got to build your credit. You’ve got to build your FICO score. You’ve got to save money for the down payment.”

Savio’s answer is, “OK, start building these units right now, but do it with equity sharing. People say, ‘We’re going to build a whole bunch of rental units and fix the problem.’ Well, we’ve tried that. We tried it in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. When are we going to realize it doesn’t work?”

Another criticism of Savio’s plan is that it reduces the already slim incentives to build affordable housing. This is true for any proposal that tinkers with the back end of the deal for developers. For example, the City and County of Honolulu wants to extend the affordable requirement for a new development from the federally mandated 40 years to 60 years. Carr explains how this change muddles the calculation for a developer.

“My fee for doing the $71 million Halekauwila deal was about $4 million. But it’s back ended. The bulk of that fee, $3.6 million of that $4 million, wasn’t paid until probably close to a year after I completed the project – after it’s all leased up, with stabilized occupancy, and it’s gone through a full audit. Meanwhile, I’ve got payroll every two weeks. Also, until a project is 50 percent completed, if there are any busts in the budgets, I’ve got to write the check to cover them. I can’t use any contingency funds. I can only use those contingency funds once I achieve 50 percent completion, because they want to make sure there’s enough money to finish the project. So, I’ve got to personally guarantee the budget line items. It’s a lot of risk.

“Yeah, I get a fee at the back end, but, if I make a mistake, it could easily go the other way and wipe my fee out. Yes, in 40 years, the building is paid off. So, in 40 years, my kids and my future grandkids will realize the value and benefit of this asset I leave behind. But look how many decades out that is. If you make it 60 years, why the hell would I want to do this? I would lose another whole generation. You’ve taken away all the incentives.”

A Better Foundation?

Duane Kurisu’s strategy to build affordable housing is basically a public/private partnership on steroids. He wants to take advantage of a little-known law that says, during a state of emergency, government agencies can exempt themselves from permitting and entitlement requirements. Last October, when Gov. David Ige issued an emergency proclamation that released additional monies to serve the homeless, he also set the stage for this sort of process.

Here’s how it would work for Kahauiki: The aio Foundation would be the developer of the project, but technically, the lessee of the property would be a government agency, yet to be determined. “The reason a government agency needs to be the owner,” Kurisu says, “is they don’t have to jump through as many hoops. They can do what they want. They don’t have to do the environmental assessment, or get an SMA approval, or get building permits. These things normally all pile up over time, but they can say, ‘You can skip this.’ ”

The idea is to speed up the process. Time, after all, is money.

That doesn’t mean building Kahauiki will be easy or cheap. It may need expensive infrastructure, like water or sewers. Also, as the developer, aio Foundation may not want to bypass some entitlement or permitting requirements. When you’re building a homeless village, it may be fine to forego installing curbs or fulfilling parking requirements, but you probably want to follow the fire and health codes. Even so, absent the usual entitlement, permitting and procurement protocols, Kurisu thinks the first stage of Kahauiki could be built by the end of 2016.

But the project is still far from certain. This is a new process and nearly every step so far has been met with a curious mix of enthusiasm and caution by public officials. Governor Ige, for example, lauds Kurisu for his willingness to not only use his own funds, but to get other members of the private sector to invest in fixing the state’s affordable housing crisis. But the governor is more circumspect about using the emergency proclamation to help.

“We’ve been very careful when we look at the emergency proclamation,” he says. “We had a lot of meetings with a lot of people, and there was a lot of concern about bypassing laws or regulations. Scott Morishige (the governor’s homeless coordinator) met with Duane Kurisu to try to understand what he does need, and what specific approvals and permits he would need help with to speed up the process.”

But the governor seems chary about making exemptions for a single person or a single project. “We need to make government work,” he says. “If there’s a bottleneck in the process, we need to fix it for everyone.”

Still, the governor didn’t specifically rule out Kurisu’s project. Perhaps a more critical snag arose when Kurisu was unable to find a state agency willing to the lessee for Kahauiki. One suggestion was to choose a different location, but that would have made the development time years rather than months. Kurisu feared that the longer it takes, the less likely it would ever be built.

Then, help came from an unexpected corner. When Kurisu sat down with Mayor Kirk Caldwell and people from the various departments at the City and County of Honolulu, he found an enthusiastic supporter.

“As each of his people came up with problems,” Kurisu says, “the mayor had answers for all of them.”

The mayor’s most important answer was straightforward: The city would be the government agency that would serve as lessee. And just like that, Kahauiki was back on track. Of course, the situation remains fluid. Until construction actually begins, the largest homeless project in the state could still founder. But Kurisu is hopeful.

And, if it’s built, Kahauiki could make a real dent in Hawaii’s homeless population – especially among families. “There are 14 acres on this property,” Kurisu says. “The architect thinks we can get 20 units on each acre. If you say there are three people to a house, that’s 840 people in total.”

Perhaps most important, Kurisu believes this approach is replicable by other developers. “The common theme that we’re hearing from state leaders is that what we’re doing is pioneering. We’re fact-finding for the business community and the public to figure out how to tackle this whole affordable housing issue.”

The Prognosis

Stanford Carr thinks the Kakauiki strategy is viable. “It should work under the emergency proclamation,” he says. “We did the same thing, about eight or nine years ago, when we did a transition out in Maili.” He notes, though, at the time, a newspaper story implied he got a sweetheart deal because he received a no-bid contract, even though no other developer was willing to do the affordable-housing project. “No good deed goes unpunished,” he says.

Carr is less sure that permitting and entitlement delays are the main obstacle to affordable housing. “Most of the work is in the studies that need to be commissioned in order to complete an application,” he says. “You have to do an environmental assessment, community outreach, traffic-impact-analysis reports, archaeological inventory surveys, Phase 1 environmental and noise studies. In certain areas, you may have to do flora and fauna surveys. You’ve got to do your due diligence to make sure there’s sufficient infrastructure to serve your project, that there is sewer capacity, water, power, drainage.”

Even so, for an experienced developer like Carr, that whole process can go relatively fast.

“From the time we started, commissioned all our studies and got Council approval by way of a resolution, it was a year.”

That’s not as fast as in Mainland cities like Houston, that have few zoning rules, but it’s not an outrageous time lag, given the environmental and zoning concerns in Hawaii. Even so, Carr thinks Kurisu’s plan is a good one, though perhaps not easy to reproduce.

“It’s a great project,” he says. “It’s benevolent of him. But not everybody has as much money as him.”

Kurisu is under no illusions about the challenges facing Kahauiki.

“In development projects,” he says, “there are usually three kinds of risk: finance risk, construction risk and market risk. But, in this case, there’s a fourth kind of risk: government risk. I think that, if this project doesn’t work, it will be because of government risk. If we cannot compress the time it takes to build the project, I don’t think it’s going to make it. That’s why we’re pressing the government so hard. If this project takes three years to get started, I think we’re going to lose the public will along the way.”