Yes, Locally Owned Has a Future

It feels like offshore-owned companies are taking over Hawaii, but the reality is their number peaked in 2007. Meanwhile, the number of locally owned companies has grown seven times faster since 1995. The same forces that ate so many local companies – globalization and technology – may now make them more viable. We profile four of these game-changing companies.

As an economist, Paul Brewbaker can explain how and why Hawaii’s economy has changed from the 30,000-foot level using statistics and charts, but this anecdote from his childhood is more powerful.

As a boy, he frequented Mrs. Tashiro’s crack seed and candy counter at Blackie Tashiro’s service station in Kaneohe. By the 1980s, the station had been replaced by a strip mall anchored by a 7-Eleven, says Brewbaker. “If there’s an IT system in which every item has a barcode, and one scan updates the entire supply chain from Iwilei all the way back to Chongqing, well, I’m pretty sure the 7-Eleven supply-chain management was more efficient because of that technology than Mrs. Tashiro (individually) buying coconut balls and lemon peel and li hing mui.”

That global buying power and efficiency translates into lower prices for customers, who vote with their feet. Plus, the global company has the capital to outbid smaller competitors when an existing local business goes up for sale or a lease renews. The bottom line is that control and profit on crack seed sales stopped flowing to the local Tashiro family and instead flow to 7-Eleven’s Dallas-area headquarters and its global shareholders.

“When you have a company that’s headquartered in Hawaii, you’re likely to have people from higher levels who are from Hawaii; they carry that Hawaii perspective.”

— Ann Botticelli, Senior VP, Hawaiian Airlines

Tim Dick tells a newer story with a similar ending. The managing director at Startup Capital Ventures, which has offices in Honolulu and Menlo Park, recalls the firm’s first round of Hawaii funding, almost a decade ago. Of the four startups in that first round, says Dick, “They all moved to the mainland because they ran out of a combination of talent or market.” One was Switchfly, a Moiliili-born company that specializes in travel loyalty program platforms. Dick says they’re now headquartered in San Francisco, with $45 million in annual revenue.

It’s no secret there has been a gigantic huli in Hawaii’s business landscape over the past two generations. Some of that shift came from local circumstances, like the decline of agriculture and the corresponding decline in power of the “Big Five” locally owned companies that dominated Hawaii’s 20th-century economy. Today, only one of the five, Alexander & Baldwin, is still in existence, with the other four sold to or merged with offshore entities and gradually broken up.

Other changes have come from the two greatest transformative forces in the business world today: globalization and technology. When Hawaii Business senior writer Beverly Creamer wrote about this topic in our August 2014 issue, another major trend she identified was that “mainland- and foreign-owned companies (now) play a much bigger role in Hawaii’s economy” than they once did – particularly in tourism, where long-term family and hospitality ownership has transitioned to a more complex scene, dominated by large, offshore private equity firms.

Now, with the prospect of Hawaiian Electric Industries, Hawaii’s largest company, becoming a subsidiary of the national energy firm NextEra, it seems a good time to ask: How important is local ownership of businesses to Hawaii – and what might the future look like for “locally owned”?

Global Happens

Globalization isn’t new, but dramatic advances in transportation, communication and technology have accelerated its pace and made it exponentially more complex – and more attractive. The gravitational pull is always to get bigger to better make use of economies of scale, says Juanita Liu, a former dean of UH’s School of Travel Industry Management: “The larger you are, the greater your potential for saving money and making money. There’s always this tendency toward larger and larger scale.”

Offshore branches move in, local companies fold or are acquired. “This is a reality in our society,” says Liu. “We are not a socialistic economy that restricts foreign ownership, as in China, or has limits to foreign ownership as they do in some Pacific Islands.”

Offshore branches move in, local companies fold or are acquired. “This is a reality in our society,” says Liu. “We are not a socialistic economy that restricts foreign ownership, as in China, or has limits to foreign ownership as they do in some Pacific Islands.”

But why should we care where local businesses are based, here or elsewhere?

“In short, high-paying jobs,” says Dick. “If you’re just a branch office, the best you have is a store manager. And then all of the other people, the executives, all the decision makers, are someplace else.” Dick describes former Island department store chain Liberty House’s transition to becoming part of Macy’s national chain in 2001: “All those people, the high-paying, really skilled jobs-the executive management, the financial management, the really good buyers, the accounting, financial services, IT – that’s all gone. Who knows where that is now. It’s probably hundreds of people, right? And the hundreds who are the most highly compensated and highly skilled.”

Creighton Arita, CEO of ike (formerly DataHouse Holdings), talks about the ripple effect that local ownership can have. “There’s a huge greater-good impact (to local business ownership) in multiple dimensions,” he says. “Studies have shown that the economic impact is much greater by a local company versus one owned by an (offshore) entity.”

Arita describes a conversation he had with a local bank executive, who said, “If mainland companies continue to branch into Hawaii and we become more of a branch economy, there’s a multiplier effect that is lost. You have one layer of sale, and then all the money is exported.”

Local Advantage

Ann Botticelli, a senior VP who oversees corporate giving at Honolulu-headquartered Hawaiian Airlines, adds that locally based decision makers often come from, and remain engaged in, the local community. “When you have a company that’s headquartered in Hawaii, you’re likely to have people from higher levels who are from Hawaii; they carry that Hawaii perspective. And they are involved in the community. They’re on (nonprofit) boards,” she says.

Kelvin Taketa, president and CEO of Hawaii Community Foundation, the state’s largest foundation, sees that involvement from the other side of the table. And although he stresses that there are examples of offshore-owned companies that have been “extremely generous,” he agrees that local owners have a great incentive to be engaged in giving and the community. “The business owners in Hawaii tend to be very close to the ground,” he says. “They know their customers very well. And they are of, and in, the community.”

There is a correlation between corporate offices in Honolulu and community generosity. First Hawaiian Bank, which had already merged with San Francisco-based Bank of the West when it was acquired by Paris-headquartered BNP Paribas in 2001, remains a very independently run foreign-owned bank – which is likely why its corporate giving program made it the top for-profit company on Hawaii Business’ Most Charitable Companies list last year, with $3,802,166 worth of cash and in-kind donations during 2013. Of the top 10 institutions on that list, all of them have corporate offices, and decision makers, in Hawaii.

A keen sense of shared destiny helps, too. Botticelli describes the state’s cultural, environmental and educational health as the health of Hawaiian Airlines. “We have a stake in making sure those areas are supported. Education, that’s our future workforce. We have a stake in making sure our students are as well-educated as they can be, from mechanics to flight attendants to our next CEO.” That’s why Hawaiian Airlines supports those areas with its donations and investments.

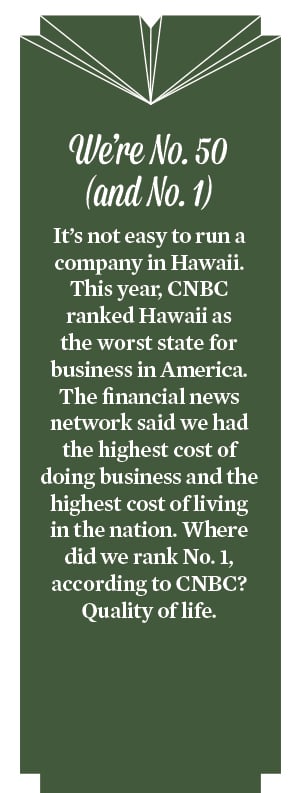

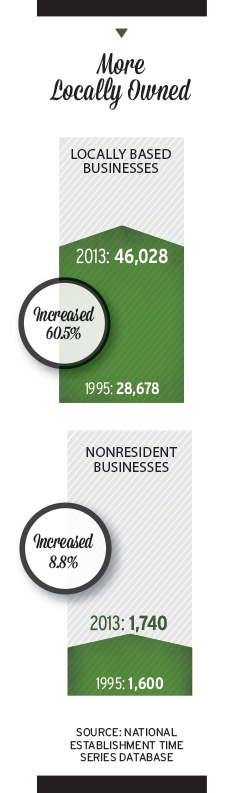

Those types of long-term investments in a community only make sense if you intend to be in it for the long haul. And just as empires retract from their distant outposts when they need to regroup, offshore companies left the state at a significant clip during and after the recession, according to the National Establishment Time Series Database, which reported 2,172 nonresident businesses in Honolulu county before the recession, in 2007, and 1,740 in 2013 – a decline of 20 percent. In the same period, the number of locally owned establishments actually rose, from 44,996 to 46,028, an increase of 2.3 percent.

Those types of long-term investments in a community only make sense if you intend to be in it for the long haul. And just as empires retract from their distant outposts when they need to regroup, offshore companies left the state at a significant clip during and after the recession, according to the National Establishment Time Series Database, which reported 2,172 nonresident businesses in Honolulu county before the recession, in 2007, and 1,740 in 2013 – a decline of 20 percent. In the same period, the number of locally owned establishments actually rose, from 44,996 to 46,028, an increase of 2.3 percent.

When a decision maker lives in and loves Hawaii, it’s easier for that person to think about bottom lines that are long range and not purely financial. Beth Whitehead, chief administrative officer of locally owned American Savings Bank (which plans to spin off from HEI after the NextEra takeover and become a publicly owned company), puts it this way: “We are an Island community, and we all have the obligation to give back to the community and help it be sustainable – and to help grow the talent and keep our kids here.”

New Local Companies

Some of the void left by the demise of the Big Five and other companies has been occupied by offshore-owned businesses. But the rest has been filled with what Taketa of the Hawaii Community Foundation calls “a corresponding, and pretty significant, growth of small- and medium-size business.”

The numbers bear this out. Carl Bonham, executive director of UHERO, UH’s economic research organization, points to another comparison from the National Establishment Time Series database, which tracks establishments over time: in 1995, the earliest available numbers, there were 28,678 local business establishments in Honolulu. In 2013, there were 46,028, an increase of 60 percent. During that same period, the number of nonresident businesses peaked in 2007, just before the recession, but overall has increased by just 140, from 1,600 to 1,740.

That Hawaii is flush with younger businesses is good news. Summarizing a white paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research, Laurent Belsie of the same institution wrote that, regardless of size, on average, “The younger companies are, the more jobs they create.”

In addition, some small businesses get much bigger – and Dick, of Startup Capital Ventures, is optimistic the latest generation of tech startups might not have to leave Hawaii to become global presences. In the almost-decade since Switchfly was founded, “technology has moved on,” says Dick, and social media, smartphones and cloud-based computing have transformed the way we live and do business. Many of these developments support smaller, agile actors, mitigating concerns about Hawaii’s workforce limitations and reducing the costs of geographic isolation.

“The whole mission behind starting DataHouse was to be able to retain the best and the brightest – to create high-value opportunities in the community.”

— Creighton Arita, CEO, ‘IKE

(formerly DataHouse Holdings)

Stay Local, Act Global

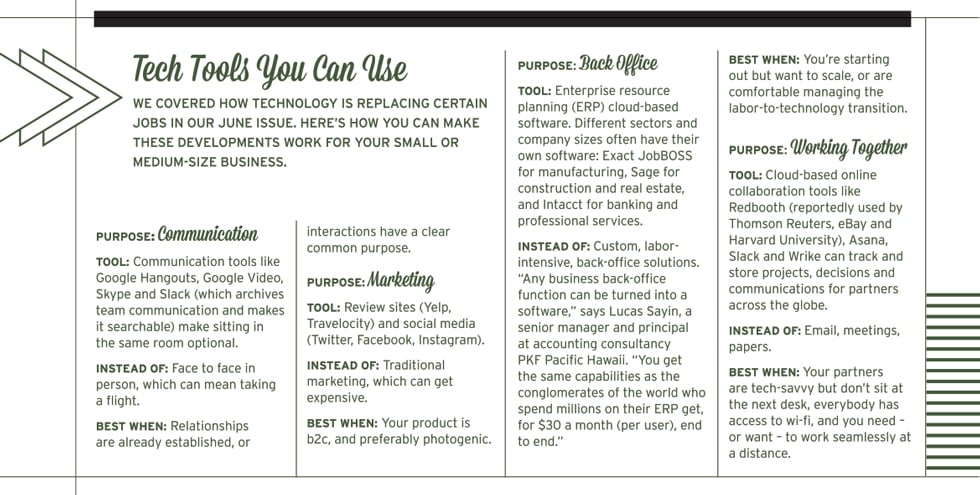

How do you thrive, as a business, in an island state in the middle of a globalizing economy, when technology is eating traditional jobs like popcorn? You widen your perspective, take stock of your (and Hawaii’s) special assets on a global scale, and then make globalization and technology work for you, says Dick: “What are the natural resources of the place, the people, the culture, and how do you build on those natural strengths?”

Dick adds that technology isn’t just a job-killer; for those willing to use its tools, tech can also be a job-creator. In the pre-jet age, Hawaii-based companies sold goods and services to Hawaii’s people, he says. Then after the jets and other modernizations, “all these giant big-box industries came in and messed everything up. But I think there are technologies and other circumstances today that can actually bring back advantage to small-scale businesses, so they can afford to stay local, but act global.”

Here are four locally owned companies, large, medium and small, young and mature, that have managed to do just that. They are all, in their different ways, attaining a global reach.

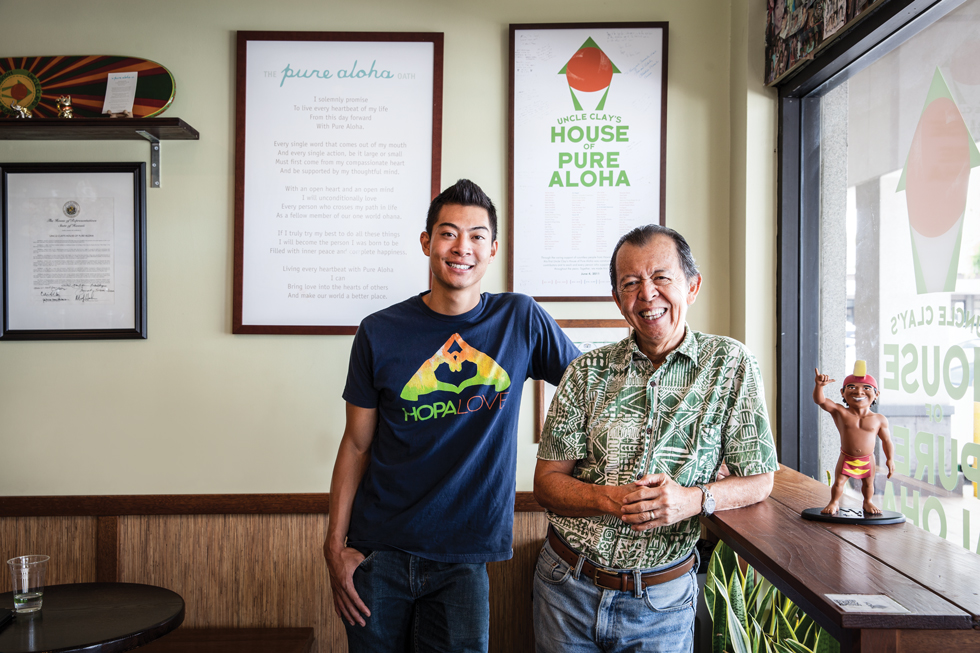

Uncle Clay’s House of Pure Aloha: The Crack Seed Store Evolves

Clayton Chang knows the pain of the crack-seed store owner: He is one. In 2010, the famously kind proprietor of Doe Fang, an Aina Haina crack-seed and Icee institution, saw the writing on the wall. “It got really rough,” says Chang. In the effort to keep Doe Fang going, Chang lost his house. But his nephew, Bronson Chang, enrolled in an entrepreneurial program at the University of Southern California, stepped into the fray. Together they came up with Uncle Clay’s House of Pure Aloha, an “evolved crack-seed store” the elder Chang says “preserves what we grew up loving,” a place for local treats that’s overflowing with aloha spirit.

Uncle Clay’s House of Pure Aloha kept its “local snack with pure aloha” mission, but pivoted its offering to focus on a treat that visitors would seek out, too. It serves shave ice made with homemade, all-fruit syrups with no artificial ingredients: mango, lilikoi, guava, strawberry, coconut and kale. The syrups are made with local-grown ingredients whenever possible.

Clayton Chang

teamed with his nephew,

Bronson Chang, to reinvent his store as Uncle Clay’s House of Pure Aloha – “an evolved crack-seed store.” Photo: Olivier Koning

In doing so, Uncle Clay’s, located two doors from where Doe Fang used to be, surfed a multitude of trends, including an increased demand for natural, local and health-conscious products and what Liu, of UH’s Travel Industry Management School, describes as a “shifting demand” in the visitor industry away from standardized experiences and toward “more custom, or more authentic, or unique experiences” that they are willing to hunt down outside of tourist centers.

But how, without a marketing budget, would visitors find them in Aina Haina Shopping Center? The Changs turned to technology with a global, 24/7 reach, building an informative, accessible website, and platforms on social media where they could engage. “Social media was a game changer,” Bronson Chang says. “We didn’t really have money for marketing, and these platforms are free. It’s what we needed.” Uncle Clay’s aloha-filled customer experience paired well with review sites like Yelp and TripAdvisor, where the people factor often means the difference between a rave and a “meh.”

As of this writing, Uncle Clay’s House of Pure Aloha is No. 1 on TripAdvisor for “Places to Eat in Honolulu.” Of its 582 reviews on Yelp, 511 are five stars. Reviewers compare Uncle Clay to a Hawaiian Mr. Rogers or Willy Wonka.

How’s business? Their success can be seen in a line that often runs out the door, an equal balance of visitors and locals – many of whom, on the day I visit, have also found the House of Pure Aloha through Yelp or TripAdvisor. You can still find prune and mango mui, but it’s next to the Uncle Clay’s merchandise and the taro chips. “I have to pinch myself every morning,” says Chang. “We’re this little mom and pop that has fought the fight. We want to be around for a long time to come.”

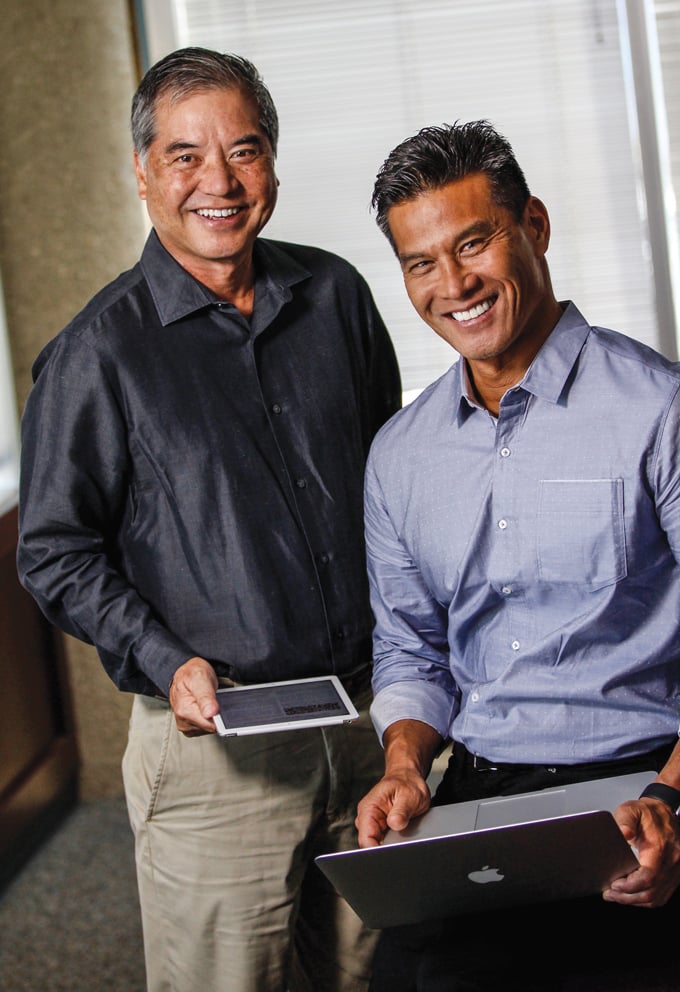

IKE: Local Headquarters, National Partners

Being in Hawaii is built into local tech and health holding company ike’s DNA (the name is the Hawaiian word for “insight” or “knowledge”). Ike started more than a generation ago as IT solutions company DataHouse, says CEO Creighton Arita, whose father, Dan, founded the company. “My dad had a vision of wanting to stop the big brain drain,” says Creighton Arita, describing his father’s work as head of IT at UH and then in state government: “The state would often bring in mainland consultants, who would learn and gain expertise, and then leave at the end of the engagement. My dad saw a lot of opportunity that could stay here in Hawaii. The whole mission behind starting DataHouse was to be able to retain the best and the brightest – to create high-value opportunities in the community.”

Dean Hirata, left, the president of ike, and Creighton Arita, the CEO of ike, which is the parent company of DataHouse, TeamPraxis and Sagely. They have created companies that deliver services nationally and globally by leveraging Hawaii’s unique attributes. Photo: Olivier Koning

So, with headquarters in Hawaii as a given, how do ‘ike’s companies (which include DataHouse, TeamPraxis and Sagely) thrive? They turn Hawaii’s self-containment into a virtue, and then find partners that can benefit from it. “Our model is built on creating (national) partnerships that will continue to allow us the ability to scale,” says Dean Hirata, ike’s president.

Take TeamPraxis, a national health information technology provider founded in 1992 by Creighton Arita. In the tradition of tech entrepreneurs, Arita looked for a “vertical” – access to an industry with a deep, preferably world-class wellspring of knowledge and practice –and found health care. “Heath care was a great vertical,” says Arita, and Hawaii was also “a great demonstration site, because of the Prepaid Health Care Act,” the state’s 1974 first-in-the-nation law that required companies to offer health insurance to all employees working 20 hours a week or more. Arita says Hawaii also had a good demographic spread, another asset for a demonstration site: “Most of the population was on Oahu, but we still had a rural component.” TeamPraxis partnered with multibillion-dollar company Allscripts in 2005, and today serves about 15,000 health care providers across the United States.

Advances in communications technology play their part in the company’s growth. “Our ability to collaborate (digitally) has really shrunk time and space barriers,” says Arita. TeamPraxis offers national round-the-clock service by “leveraging time zone differences” and offshoring the “graveyard shift” to India, says Arita, who adds that “it would be literally impossible to hire the same quality and amount of labor in Hawaii” for a night shift.

Another ike company, Ekahi Health System, is a healthcare delivery organization that coordinates care among small, independent providers. Ekahi partners with HMSA and national well-being and healthcare company Healthways. A third ike company, Sagely, offers a mobile, cloud-based app that serves the growing number of caregivers with a loved ones in a senior living community, allowing them to see what the senior’s day was like. “The social aspect is a real indicator of a resident’s health,” says Hirata. Sagely, too, is creating partnerships beyond Hawaii.

Today, ike’s health and tech companies employ around 300 people locally, and they are growing. Arita says that in the last six months they have made “several” acquisitions.

“It is a challenge (to do business in Hawaii),” says Arita, “but our success is grounded in the ways Hawaii is unique. With technology, it’s possible for us to leverage the unique attributes Hawaii has to offer, and to be able to create scaleable IP (intellectual property) that can compete nationally and globally.”

Hawaiian Airlines: The Superconnector

It used to be a business cliche to imagine Hawaii as a “global crossroads of the Pacific” – and sometimes it has been hard to see how it would ever come to pass. But Hawaiian Airlines just might do it.

This year, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University’s and Wichita State University’s Airline Quality Rating Report rated Hawaiian Airlines second among all U.S.-based domestic carriers on a number of criteria, including customer experience. Hawaiian’s hope, says senior VP Ann Botticelli, is that its Hawaii in-bound fliers will be able to turn what is often an ordeal into two extra days of destination: “When you step on that plane, you feel like your vacation already started.”

Mark Dunkerley has led Hawaiian Airlines on an Asia-Pacific expansion that uses Hawaii as a superconnector hub – making good on the longtime idea that the Islands are the Crossroads of the Pacific. Photo: Olivier Koning

While other domestic carriers have removed free meals, Hawaiian has put celebrity chefs into the mix, and revamps its in-flight meal menu every six months. That kind of service reminds us more of elite international airlines like Singapore, Emirates and Cathay Pacific, all known for their pleasant, culturally branded in-flight experience.

Is it part of a plan to grow into a global powerhouse? “What we’ve been doing since 2010 is a very purposeful expansion into the Asia Pacific region,” confirms Botticelli. “I think that’s how we grow and remain headquartered in Hawaii – we grow outside Hawaii, to places like Beijing. We think there’s an (untapped) market of people who are very interested in a Hawaiian vacation.”

Dick, of Startup Capital Ventures, is intrigued by what he calls CEO Mark Dunkerley’s “emerging vision of Hawaiian Airlines as a superconnector of the Pacific.” Dick says that Hawaiian Airlines resembles Emirates in more than service: Emirates uses Dubai as a hub between huge population centers. “Dubai is basically midway between the 350 million people who live in Europe and the couple of billion people who live in Asia. And Honolulu occupies a similar position in the Pacific: Couple of billion people in Asia, and (then) all of the Americas. If you look at (Hawaiian Airlines’) fleet plans, you can see how he’s putting it together, step by step.” Dick adds that a stopover in Hawaii, like Dubai, is in essence an added bonus: “In Dubai, they have a two- or three-day shopping experience. Well, who wouldn’t want to stop by Honolulu for a couple of days? (Hawaiian Airlines has) an opportunity to do something very interesting here.”

Contix: A Tropical Bluebird

On April 28, 2015, Twitter’s stock price plunged 18 percent in the last hour of Wall Street trade, when a financial intelligence platform accidentally released Twitter’s earnings almost an hour early, on social media. The plunge caused a national flap among financial types, but among the few not taken by surprise – and able to act quickly on the information – were clients of Contix, a company that sifts the 500 million daily messages released on social media for actionable information and sends alerts to

its users.

Contix is headquartered in Honolulu. Its founders were not born or raised in Hawaii, and its fintech (financial technology) product is clearly global in nature. Dick describes the company as a “bluebird,” a wholly unexpected success. “There’s no (financial) trading industry in Hawaii, but you had a few guys that developed the knowledge, and they’ve now built a world-class platform they’re selling to clients in New York. London’s probably next,” he says. “I’m guessing this business could be very sizeable in terms of revenue with less than a hundred people.”

What will keep Contix from being forced to move to the Bay Area to scale up? In the last few years, says CEO Ryan Bailey, a lot has changed. For one thing, “videoconferencing technology has gotten so much better and so much cheaper,” and finding and retaining employees is no longer the intractable problem it was even five years ago.

Bailey has worked hard to find a locally based core team. When one of them moved back to India, Contix kept working with him. Another Honolulu-based Contix employee moved to Hawaii Island and has also remained with Contix. “Every day,” says Bailey, “we just get connected and we all talk about what we worked on yesterday and will be working on today via Google Video. It’s high-quality.”

Contix CEO Ryan Bailey is building a company with a global reach that uses videoconferencing and other technology so it can remain based in Hawaii. For instance, his core team is based in Honolulu, but has important employees based in India and Hawaii Island. Photo: Olivier Koning

Geographically dispersed teams are now becoming more and more common, says Dick: “It’s now much easier, and in some cases the norm, to have your technology development organization spread pretty far around the world.” Dick also cites collaborative software-building platforms like GitHub and other development tools that make long-distance collaboration more seamless.

Bailey talks of satellite offices in New York and London, but Contix has no plans to move its headquarters. “I’ve just sort of fallen in love with Hawaii,” says Bailey, “and my (business) partner feels the same way. We really like the culture, the people, the physical beauty. People have a more balanced life.”

Right now, Contix has a core team of 13 (10 based in Honolulu), but they think that when the time comes to scale up, Hawaii’s No. 1 spot in national quality-of-life surveys will be a selling point for potential recruits.

“I do think there’s a growing awareness among knowledge workers that there are other ways of living life besides the Silicon Valley ethos of all work and no play, and I think Hawaii offers that,” says Bailey. “We work very hard, and we’re very motivated. We’re just as competitive as the mainland-based firms, but, at the same time, there’s more to it. You can’t live a deferred life. You can live a balanced, fulfilling life, and yet at the same time work on really interesting, deep technical problems. That’s what we’re doing here, and that’s the attraction.”

Viil Lid is the co-founder and CTO of Honolulu-based tech startup MeetingSift, another company whose product has no overt Hawaii connections, but whose founders like Hawaii’s quality of life. “I think this is part of a general trend that has been building up over the past decade in the technology industry,” says Liid. “With cloud computing and the Internet as a product-delivery channel, you can serve global customers from any location, no matter where your company is located geographically. So, if you can run your company from anywhere, why not Hawaii?”

The Future

Groups as diverse as UH and the Hawaii Business Roundtable have identified innovation as the most promising potential “third sector” of Hawaii’s tourism- and military-heavy economy. One big drawback of business in Hawaii is the expense and time-cost of shipping – but that’s negated when your product is intellectual property, which can be sent and received instantly, and has an essentially infinite value-to-weight ratio.

But technological innovation has a symbiotic relationship with traditional sectors, relying on existing wells of industry knowledge that it can turn to for ideas and use as a testing ground. Verticals feed the innovation economy and, in Hawaii, the innovation economy can make it more viable for traditional businesses to remain headquartered here.

Dick hopes that, at some point, one or more tech companies in Hawaii will reach a tipping point, where they cease to be startups and become established parts of the landscape. At that point, says Dick, the state will start attracting back the significant portion of its tech community that is skilled but “risk-averse. The ones that are smart technically but don’t want to live the startup life cycle.”

“I think there’s a lot of opportunity in these spaces,” says ike’s Arita. “It’s really a different world, now. We believe people can live in Hawaii and not sacrifice their personal growth and opportunities. It’s not there yet; we feel like we’re helping pioneer this. But we believe people can have their cake and eat it, too.”