Which NextEra Will Hawaii Get?

Soon after NextEra Energy stirred up debate in the local energy community by announcing plans for a $4.3 billion takeover of Hawaiian Electric Industries, Ted Peck called us to put in his two bits.

Like other media outlets in town, Hawaii Business scrambled to put the proposed merger into perspective. We sat down with executives from the two companies to hear why they thought the deal was in the best interest of ratepayers and shareholders. We spoke with a half-dozen utility experts about the business model of the new company and whether the deal would pay off. We listened to renewable energy advocates worry about the merger’s impact on the local solar industry and about Hawaiian Electric’s big move from oil to liquid natural gas (LNG). And we spoke with almost everyone about what to expect from the Public Utility Commission, which will have the last word on this merger, and, lately, has been uncharacteristically critical of the utility.

In other words, we wanted to figure out what this mammoth new utility would look like.

Peck’s Quarter

Ted Peck has always had an idiosyncratic view of Hawaii’s energy future. He was the state energy administrator during the Lingle adminstration and the president of Kuokoa, a company that once tried to buy HEI. Yet, this time, Peck’s perspective is the most straightforward we’ve heard.

“The NextEra deal is really an ancillary question,” he said. “What I would do is run a story with a picture of a quarter on the cover of the magazine. Because, that’s the real question: Can the utility get the price of electricity down to 25 cents per kilowatt-hour? If it can’t, then the merger doesn’t matter; distributed generation of all sorts – whether it’s solar or combined cycle generators or whatever – is going to take over. People are going to fire the utility if it’s more than 25 cents. Because they can.”

That seems like an excellent place to start thinking about what this deal means to Hawaii, because it’s a reminder that the proposed NextEra/HEI merger is happening during a period of great uncertainty for the state’s energy ecosystem. A reminder that, as we design an energy system for the future, the deal has to work now, too.

So, for Peck, the quarter is a sign the system is working. He says it’s not an abstraction; it’s pretty much what large customers can expect to pay in the near future if they go off the grid.

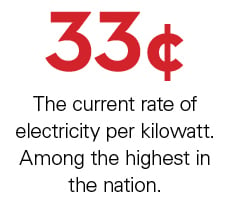

“If large energy takers want electric power at 25 cents a kilowatt, they can do it. Even with the cost of storage included, solar is already at or below grid-parity.” Remember, Hawaii pays some of the highest electric rates in the country – 33 cents a kilowatt on Oahu and more on the neighbor islands. The only reason more large customers haven’t already gone off the grid, Peck says, is because they’re not yet willing to shoulder the risk of running their own utility. But that time is coming. Hawaii Gas, which is in a race with HEI to bring LNG to the state in bulk, says it’s already pitching the idea of natural-gas generators to some of HECO’s largest customers. This is the context in which the merger plays out.

So the question is whether NextEra can speed up the process of “getting to a quarter,” as Peck puts it. And can it do that while still meeting the ambitious renewable-energy goals of the Hawaii Clean Energy Initiative? It’s hard to tell just by looking at NextEra’s record on the mainland.

Who is NextEra?

When it comes to renewable energy, NextEra is a schizophrenic company. On the one hand, its NextEra Energy Resources subsidiary (NEER) is the nation’s largest developer of renewable energy. With facilities in 27 states (plus Canada and Spain), it produces about 17 percent of the country’s wind power and 14 percent of its utility-scale solar power. Most of this comes from wind and solar farms designed and built by NEER. This is a company that clearly has the expertise and resources to speed up Hawaii’s move to clean, renewable energy. In fact, on Hawaii Island, Parker Ranch recently announced plans that allow NEER to develop its wind resources.

On the other hand, Florida Power & Light (FPL), NextEra’s other major subsidiary, is a much more traditional, vertically integrated electric utility. Its portfolio of natural gas, nuclear and coal-fired power plants produce over 24,000 megawatts of electricity for 4.7 million customers. It owns thousands of miles of power-transmission and distribution lines. It’s one of the nation’s largest consumers of natural gas and is in the middle of a $1.8 billion pipeline project. But it’s not exactly a renewable energy powerhouse (unless you count its four nuclear plants). According to Florida energy insiders, FPL successfully lobbied against the creation of renewable energy portfolio standards for the state, which would have codified the inclusion of more renewable energy onto the grid. The company also has a reputation for being antagonistic to customer-owned rooftop solar. Much of this criticism is hearsay, but the fact is less than 1 percent of FPL’s power comes from wind or solar. That’s in stark contrast with sister company NEER.

On the other hand, Florida Power & Light (FPL), NextEra’s other major subsidiary, is a much more traditional, vertically integrated electric utility. Its portfolio of natural gas, nuclear and coal-fired power plants produce over 24,000 megawatts of electricity for 4.7 million customers. It owns thousands of miles of power-transmission and distribution lines. It’s one of the nation’s largest consumers of natural gas and is in the middle of a $1.8 billion pipeline project. But it’s not exactly a renewable energy powerhouse (unless you count its four nuclear plants). According to Florida energy insiders, FPL successfully lobbied against the creation of renewable energy portfolio standards for the state, which would have codified the inclusion of more renewable energy onto the grid. The company also has a reputation for being antagonistic to customer-owned rooftop solar. Much of this criticism is hearsay, but the fact is less than 1 percent of FPL’s power comes from wind or solar. That’s in stark contrast with sister company NEER.

So, the question of whether the merger will help Hawaii extricate itself from its dependence on imported oil will largely depend on which NextEra Hawaii gets.

Capital

Whichever NextEra we get, one big upside to having a utility that’s a Fortune 200 company is its ability to secure and deploy capital. That’s key, because the utility industry is one of the most capital-intensive sectors of the economy. Part of that is simply because it’s expensive to build and operate the enormous infrastructure of a major utility. HEI, for example, is facing major investments in things such as grid modernization and the conversion of old oil-burning power plants to more efficient LNG plants.

But the business model of a traditional utility also contributes to the industry’s capital-intensive nature. As a regulated industry, utilities have historically operated on a “cost-plus” basis. In other words, regulators typically allow them to earn a certain profit – up to 10 percent, in the case of HEI – over and above their approved expenses. Capital costs are a big part of those expenses, so the larger a utility’s capital investment – the more generation plants, transmission lines, etc. – the more money it can earn. Naturally, this incentive is offset by the cost of capital. So, the more cheaply you can borrow, the more you can invest, the more profits you can earn. Rates are also based, in part, on the cost of capital, so a utility’s size is important for customers as well as shareholders.

But the business model of a traditional utility also contributes to the industry’s capital-intensive nature. As a regulated industry, utilities have historically operated on a “cost-plus” basis. In other words, regulators typically allow them to earn a certain profit – up to 10 percent, in the case of HEI – over and above their approved expenses. Capital costs are a big part of those expenses, so the larger a utility’s capital investment – the more generation plants, transmission lines, etc. – the more money it can earn. Naturally, this incentive is offset by the cost of capital. So, the more cheaply you can borrow, the more you can invest, the more profits you can earn. Rates are also based, in part, on the cost of capital, so a utility’s size is important for customers as well as shareholders.

HEI president and CEO Connie Lau points out what that means for this merger.

“Because NextEra is about 10 times our size, it has a much better credit rating, so things like the cost of debt are a lot less expensive. And, because rates are based on costs, a lower financing cost really goes directly to the customers’ benefit.”

Eric Gleason, president of NextEra Energy Hawaii, elaborates. “All the ratings agencies have opined on this transaction. Standard & Poor’s, in particular, has said that, if the merger were to close tomorrow, Hawaiian Electric would be upgraded from BBB- to A-. That’s a three-notch upgrade from today, which is just one notch above non-investment grade – or junk – to a very strong investment-grade credit rating. That’s pretty strong evidence that the company will be on a much sounder financial footing, with low-cost access to debt. … I don’t want to oversell that. It wouldn’t happen Day One. For the debt you’ve already issued, you’ve still got to pay your interest. But, over time, as you raise new debt, in all market environments, there’s going to be a cost advantage for being an A- issuer versus being a BBB- issuer.”

Experience

The merger with NextEra doesn’t just represent better access to capital. There’s also the matter of experience. Most analysts describe NextEra as a well-run, enterprising company that, in many ways, is at the forefront of the utility industry. FPL, its Florida utility, for example, has spent billions of dollars upgrading and reinventing its infrastructure. Over the past decade, it has replaced most of its old coal- and oil-burning generation plants with state-of-the-art natural gas equipment. In the process, it has steadily driven down rates for its customers, while simultaneously slashing the company’s carbon footprint. These are skills that will be critical as Hawaii shifts from oil to LNG and, eventually, to renewables.

Similarly, Lau points to FPL’s experience with the so-called smart grid. Almost all utility experts describe the smart grid as essential to the future integration of large amounts of distributed generation, like customer-owned solar PV. But HEI’s companies have been a curiously slow at implementing this technology. There have been modest pilot programs on both Maui and Oahu, with HECO just finishing up the installation of smart meters on 5,200 homes. But Lau believes the merger could radically accelerate the growth of Hawaii’s smart grid.

Similarly, Lau points to FPL’s experience with the so-called smart grid. Almost all utility experts describe the smart grid as essential to the future integration of large amounts of distributed generation, like customer-owned solar PV. But HEI’s companies have been a curiously slow at implementing this technology. There have been modest pilot programs on both Maui and Oahu, with HECO just finishing up the installation of smart meters on 5,200 homes. But Lau believes the merger could radically accelerate the growth of Hawaii’s smart grid.

“NextEra, using the same software vendor we use, has almost all its Florida customers – 4.7 million of them – already on a smart grid. So, it now has some specific data and experience operating a smart grid and has been able to demonstrate some specific cost savings that will really help us as we go to our PUC to get approval to move beyond the pilot stage and move the smart grid out to all the islands.”

These are relatively simple examples of the kinds of resources NextEra would bring to Hawaii. Interestingly, there’s at least one area where NextEra can learn from HEI. Although it’s something of a sport in Hawaii’s energy circles to bash HEI for being slow and recalcitrant in allowing more distributed generation – mostly PV solar – onto the grid, the truth is that Hawaii’s 10 percent distributed generation level is far and away the highest in the country. The national average is less than 0.2 percent, which is more or less what NextEra’s FPL subsidiary gets from wind or solar. Similarly, although NEER is the largest producer of renewable energy in the country, it’s a wholesaler, not a utility. This means NextEra has very little experience with integrating distributed generation into the grid. In this sense, Hawaii is the industry leader, and may serve as a testbed for NextEra’s mainland operations.

Rooftop vs. Utility Scale Solar

The merger announcement has also provoked controversy, particularly within Hawaii’s solar-energy community, which already feels threatened by HEI policies regarding PV installations. The problem for NextEra is its reputation for preferring utility-scale solar over rooftop solar.

Gleason suggests the company is in basic agreement with the renewable goals embedded in the power supply improvement plans HEI filed with the PUC in August (a controversy we’ll come back to). He also takes exception to the criticism of NextEra’s own record on renewables, even in Florida.

“First of all,” he says, “we recognize that PV, rooftop or otherwise, is important in Hawaii. Hawaiian Electric has filed plans with the PUC that state its goal to triple PV solar through 2030. We said we support those goals. We think it’s the right direction for Hawaii. The reason you see less solar penetration in Florida – in particular, rooftop solar – is simply because it’s not as attractive to customers. We have net-energy metering in Florida, at full retail rates, just like you do in Hawaii. The difference is that our retail rates aren’t 30-something cents a kilowatt-hour. They’re about 10 cents a kilowatt-hour. So, as a customer – and I’m a customer and a homeowner – it’s just not very appealing to actually put solar panels on your roof.”

“First of all,” he says, “we recognize that PV, rooftop or otherwise, is important in Hawaii. Hawaiian Electric has filed plans with the PUC that state its goal to triple PV solar through 2030. We said we support those goals. We think it’s the right direction for Hawaii. The reason you see less solar penetration in Florida – in particular, rooftop solar – is simply because it’s not as attractive to customers. We have net-energy metering in Florida, at full retail rates, just like you do in Hawaii. The difference is that our retail rates aren’t 30-something cents a kilowatt-hour. They’re about 10 cents a kilowatt-hour. So, as a customer – and I’m a customer and a homeowner – it’s just not very appealing to actually put solar panels on your roof.”

He says the story is much the same for utility-scale projects, which are, after all, the bread and butter of NextEra outside of the Sunshine State.

“Florida Power & Light has invested in 110 megawatts of utility-scale solar projects that are up and running today. That’s actually more than any other utility in the state, and we would love to do more. But the rule in Florida, by statute, is that the utility, with only limited exceptions – including those 110 megawatts – has to procure the most cost-effective energy generation for customers. And, up until now, solar has not been able to meet that test. We love solar. We’ve made the case to do more solar. As soon as there was a legislative carve-out that allowed us to do 110 megawatts, we jumped on it. Given how the cost of installing solar has declined in recent years, we’re just now in a situation where we believe there’s an opportunity to install new utility-scale solar in Florida and meet that cost-effective standard. For those who would suggest we’re not huge advocates of solar, in Florida or elsewhere, that’s just not the case.”

This raises two points. First, FPL generates over 24,000 megawatts a year for its customers, 90 percent of it coming from either natural gas plants or nuclear reactors. That means 110 megawatts of solar is chump-change in a state the size of Florida. But it’s NextEra’s emphasis on utility-scale production that has alarmed some people in Hawaii’s energy community. Hawaii, after all, leads the nation in distributed generation, with almost 10 percent of its power coming from rooftop solar. This isn’t an accident. It’s the rational response to the highest electric rates in the country and public policies, such as net energy metering and large tax credits, which reward customers for producing their own electricity.

This is another area where NextEra claims it’s in basic agreement with what HEI is already doing.

“Technology is changing in the industry,” Gleason says. “It’s making distributed-energy resources accessible – not just rooftop solar, but demand response, storage, customer choice, options that would have been pie in the sky or fantasy 20 years ago, or even 10 years ago. Hawaiian Electric is embracing that. They’re looking at how they can improve the value proposition and choice for their customers. We support their plans to do that. I wouldn’t view this as any change in direction from the transformation that (HECO) is talking about.”

HECO president Alan Oshima agrees. “From our perspective, one of the great things about our partnership and our discussions to date is that we’re really very aligned about the direction Hawaii needs to move. They’ve looked at our plans, both in distributed generation and our power-supply-improvement plans, and they like what they see.”

Of course, HEI has also shown some preference for utility-scale projects. (“All utilities do,” says Peck.) In fact, a NextEra proposal to build a 15-megawatt solar farm in Waianae is currently under review at the PUC. The truth is that utility-scale projects are easier for the utility. Because they’re connected on the distribution side of the grid, they don’t present the integration problems that rooftop solar does. That probably makes them more cost effective as well. Cynics, of course, point out that utility-scale projects – particularly if they’re owned by the utility – are also more profitable. More subtly, as distributed generation penetration grows, it impinges on the utility’s business model. In a report prepared last year for the U.S. Department of Energy, researchers at the Berkeley National Laboratory found that increasing the number of PV customers to the 10-percent level we have here in Hawaii could cut a utility’s return on equity by as much as 18 percent, while also increasing the average customer’s rates by as much as 2.8 percent.

But local experts, like former PUC commissioner John Cole, say the cost factor may not apply as well in Hawaii as it does on the mainland. “I think it’s true,” he says, “that they lobby hard for central over distributed generation in Florida, probably using the cost-savings angle. But I think Hawaii has been traveling in another direction for quite a while, with a competitive-bidding requirement for utility projects and the success of distributed photovoltaic here. I think most people, from the legislators, to the regulators, to the utilities themselves – even though they may be of a mind to slow PV down a little bit – have the mindset to enable more distributed generation on the system. Whereas it seems like NextEra would prefer the other way: go utility scale, using LNG to keep prices down.”

But local experts, like former PUC commissioner John Cole, say the cost factor may not apply as well in Hawaii as it does on the mainland. “I think it’s true,” he says, “that they lobby hard for central over distributed generation in Florida, probably using the cost-savings angle. But I think Hawaii has been traveling in another direction for quite a while, with a competitive-bidding requirement for utility projects and the success of distributed photovoltaic here. I think most people, from the legislators, to the regulators, to the utilities themselves – even though they may be of a mind to slow PV down a little bit – have the mindset to enable more distributed generation on the system. Whereas it seems like NextEra would prefer the other way: go utility scale, using LNG to keep prices down.”

A related issue is the question of who should own these utility-scale projects. Hawaii law requires HEI to get competitive bids for them. As a result, much of HECO’s renewable power comes through power-purchase agreements with IPPs – independent power producers. For a well-capitalized company like NextEra, though, it would probably be more profitable to build its own facilities, which likely would also lower rates for customers. But, for a regulated utility, the risk associated with that kind of development would be borne by those same ratepayers. (This would also be true for big-ticket items such as an LNG regasification plant or an undersea cable, both of which would probably be attractive projects for the utility to undertake if the merger goes through.)

Gleason acknowledges the concern, but he thinks critics are comparing apples and oranges.

“Let me start by saying we want to do the right thing for customers. Those may not be the same things in Florida and Hawaii. I’ve just given you one example where the economics are different in Florida than in Hawaii, and the priorities are different. We can talk about why things are done the way they’re done in Florida. But, speaking to Hawaii, we’ve said we’re agnostic and open-minded and interested in stakeholder input as to whether we should be developing generation projects within the utility, or apart from the utility, like an IPP. We can do it either way. We’re big utility developers in Florida, and we’re big IPP developers in the rest of North America, so we’re open-minded about it. Whatever’s best for the customers.”

LNG

Maybe the area in which the goals of HEI and NextEra are most closely aligned is the plan to move from oil to liquid natural gas. That’s because, from a utility’s point of view, LNG makes perfect sense. For renewable advocates, though, the picture is more ambiguous.

Sebastian “Bash” Nola, an energy consultant for the renewable advocacy group Blue Planet Foundation, sketches out the quandary.“Right now, LNG is cheaper than other imported fossil fuels. Also, LNG prices, I believe, are dropping along with the price of oil, and oil is currently below $50 a barrel. But, you’ve got to be careful. A few weeks ago, oil was $70 a barrel. Overnight, it could change back to $100 a barrel. So, if you want to get lulled into the idea that oil is always going to be $50 a barrel, or will go back to $30 or $20 a barrel, like back in the early 1980s, you’re dreaming. It’s not a realistic assumption you’d want to base your planning on.”

But Nola acknowledges that LNG addresses a number of problems for Hawaii. For example, it avoids the risk of buying expensive foreign oil, one of the primary goals of the Hawaii Clean Energy Initiative. Having a reliable supply of LNG with long-term contracts will also help stabilize rates for customers. Just as important, the utility will also save a lot of money on required infrastructure upgrades.

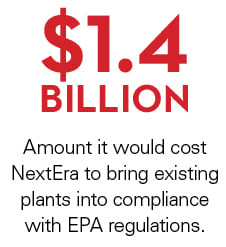

“By going to LNG,” Nola says, “they basically avoid a $1.4 billion expenditure to bring their existing plants into compliance with EPA regulations. They’re still going to have to make some investments to modify the existing oil-burning plants so they can burn LNG. So, there’s still some capital investment, but it’s not $1.4 billion.”

Despite the obvious benefits from moving to LNG, Nola worries that NextEra (and HEI) view it as a long-term solution. “I’m a renewable proponent,” he says. “For LNG, I would say it makes sense if, in fact, it’s just a transition fuel to get us to a renewable energy foundation.”

It will be hard, though, for a company like NextEra to walk away from an LNG infrastructure once it’s built. That’s probably why it makes renewable energy advocates nervous: it institutionalizes low-cost fossil fuel.

Today, there are two players moving to create Hawaii’s LNG infrastructure: NextEra/HEI and Hawaii Gas, itself owned by a mainland corporation, Macquarie Infrastructure Co. Ted Peck puts it bluntly: “In my view, whoever is the first to build a gasification plant will be the winner for the next half century in providing fossil fuels to Hawaii. We’re not going to have two gasification plants, like we’ve had two refineries.”

Known Unknowns

Maybe the most intriguing thing about the NextEra/HEI merger is its timing. Blue Planet executive director Jeff Mikulina points out that NextEra has crafted this deal without some basic information. For example, HEI’s business model – how it gets compensated for services – is in flux. Until 2013, it operated like a traditional utility, generating power and selling it to customers. The more electricity those customers used, the more money HEI made. This created perverse incentives for a company that was supposed to be promoting efficiency and the adoption of renewable energy. So, the PUC approved a new compensation model that decoupled the company’s earnings from how much energy it sold, basing them, instead, on a percentage of the company’s costs. This decoupling was an improvement, but advocates like Mikulina think it’s still too favorable for the utility.

“This is the most powerful knob we have as far as controlling the utility – how we reward it. And I don’t think anyone agrees, except for some shareholders, that the current model works very well: You spend a billion dollars and we’ll give you 10 percent on top of that, and it’s up to the PUC to determine whether that’s a reasonable investment.”

Now, Mikulina says, the PUC is considering alternatives to this decoupling plan.

“What Blue Planet is currently advocating – and we think the commission is sympathetic – is an entirely different model. One that gets away from this cost-plus approach and, instead, rewards the utility based on performance incentives – on the things that we want to see: everything from customer satisfaction, to interconnecting renewables, to being more efficient in how it operates the grid. This is called Incentive Based Regulation, or IBR.”

If the PUC approves such a radical change in rate structure, the utility that NextEra ends up with might be very different from the one it bought.

That’s not all. Last May, HEI submitted its long-awaited Integrated Resources Plan to the PUC for review. The IRP was essentially intended to be the utility’s roadmap to the future. In it, HEI laid out its plans for how it will meet its commitments under the Clean Energy Initiative. In a scathing report (for a regulatory agency, anyway), the PUC turned down the IRP and said HEI had to come back in three months with a new plan. This new document, the Power Supply Improvement Plan, which HEI submitted in August, is now under review by the PUC. But, until this or some other plan is approved, it’s unclear what the future of the utility will look like.

“I think,” Mikulina says, “the question to ask is: What’s the motivation for NextEra to buy the company today, without knowing how the decoupling docket is going to evolve, and how the utility’s Power Supply Improvement Plan is going to be resolved? Maybe they think, looking at the long view, there’s a capital market, and the utility’s going to do OK regardless of the outcome. But I guess we see things differently. We see this decoupling docket as a critical policy decision for the state.”

All of this puts the PUC in the driver’s seat, says Ted Peck.

“On most other issues, the PUC is just in a reactionary mode,” he says. “The utility says, ‘Here’s my rate case,’ and the PUC has to react to it. It’s a home game for the utility. The utility has the initiative and can define what’s going to happen. In this case, though, the statutory requirement for the PUC is very limited. It has a wide degree of latitude – basically, it just needs to be in the interests of the ratepayers. So the PUC can really dictate terms.

“If I were a commissioner, I would say, ‘What’s your business plan?’ So, this is a unique view behind the curtain for the commission. If NextEra wants the deal to be approved, it’s going to have to explain the financials and how it’s going to make money. And if the business plan it puts forward is not in line with the policy of the state, I think it’s incumbent on the commission to say, ‘No.’ ”