Which Employee Is Most Likely to Steal From You?

Experts say there are things to watch for and ways to prevent theft in the first place

If employees are going to steal from their company, there’s one clear signal, says Hawaii forensic accountant Felice Valmas, whose profession focuses on ferreting out fraud in the business world.

They will complain about low pay.

“The common thread among employees who steal is the belief they’re not being paid enough,” says Valmas, who has had a long career unearthing bad apples at companies in Hawaii and on the Mainland.

“The person complaining most frequently about being underpaid is likely the thief. They also must have access to assets and have a financial need. While a lot of people have financial need, they really also have to believe they’re underpaid.”

Valmas has seen a broad spectrum of fraud and abuse by employees. An especially egregious example occurred during her years on the East Coast. It involved a woman responsible for paying mortgage and utility bills for the company where she worked.

“There were about 50 utility payments to various addresses,” said Valmas. While most of the payments the employee was making were legitimate, some were going to the woman’s own rentals – a practice that wasn’t discovered until a forensic accountant investigated.

Abuse often involves businesses that take in a lot of cash, says Valmas. One case involved a country club that received cash daily that “was not being deposited for increasingly long lengths of time.” When Valmas did an audit, she discovered an employee was pocketing some cash, then using receipts from the following day to cover it up. The employee always expected to pay it back, said Valmas, but as weeks went by, she had taken more and more cash and couldn’t make it up with the next day’s receipts.

One way to prevent the theft of cash is to stop accepting cash, says Ben Osbrach, a partner with the nationwide company, Skoda Minotti, which has about 20 clients in Hawaii.

He points to the airline industry, where customers must pay with a credit card. “The airlines took all the cash handling out of the hands of airline personnel. There are a number of industries going that way, where they don’t want people to actually touch the cash,” says Osbrach, who specializes in IT risk and cybersecurity.

Valmas offers this simple way to help prevent theft: “My No. 1 recommendation is that employers pay employees fairly. And if you have employees with unrealistic salary expectations, you should talk to them or find them another job. You don’t want people there eight hours a day who don’t think they’re paid fairly. They will take home tools or embezzle or not act in the employer’s best interest.”

Valmas offers this simple way to help prevent theft: “My No. 1 recommendation is that employers pay employees fairly. And if you have employees with unrealistic salary expectations, you should talk to them or find them another job. You don’t want people there eight hours a day who don’t think they’re paid fairly. They will take home tools or embezzle or not act in the employer’s best interest.”

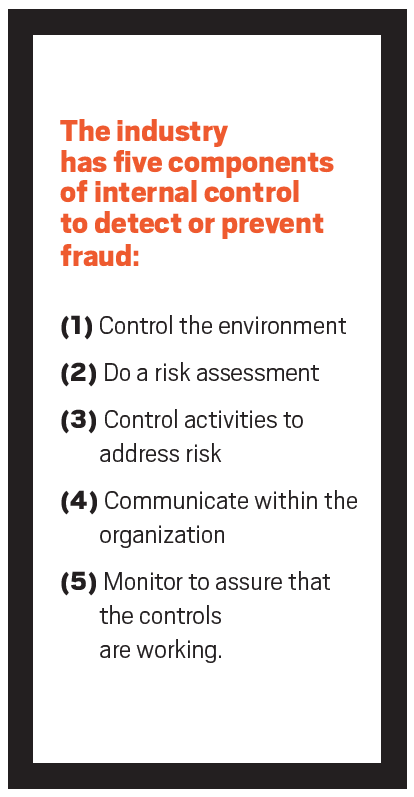

There are other safeguards employers can install. “The industry has five components of internal control to detect or prevent fraud,” says Valmas. These are: control the environment; do a risk assessment; control activities to address risk; communicate within the organization; and monitor to assure that the controls are working. They may sound simple, but they can be difficult to implement.

“Management has to be committed to maintain these controls and not bypass them,” Valmas says. “For instance, you need computer passwords, locked storage areas and manager approvals and paper documentation.”

“Have a limitation on who has the authority to approve payments,” says Valmas. “If there’s cash, you need to address the cash issues. You’ll need locked cash registers. If there are a lot of different vendors, in theory someone could have a friend (in the company) who pushes through their invoices although a service wasn’t provided. So look at what assets and transactions are most vulnerable.”

Valmas suggests owners of small companies always look at the general ledger and make sure they’re aware of what payments are being made. “They should look at bank statements and make sure deposits of cash are being made every day.”

Forensic accountants can help them develop procedures that limit the opportunity for fraud “by having appropriate segregation of duties, and having multiple people reviewing operations.”

“You want the owner and manager to be reviewing the financial information,” Valmas says. “You want someone doing the bank reconciliation who is not the person performing the transactions. Segregation of duties is a critical thing. It’s important to have limitations on the authority to authorize transactions and to have independent checks.”

Osbrach says companies must establish checks and balances within the financial operation. “If you give someone too much control, without oversight, there are opportunities for theft,” he said. “Hire qualified candidates, with background checks, to make sure you’re not hiring someone with a previous record.

“If you have an accountant who has complete control of your books, and there isn’t someone reconciling the accounts, people can do all sorts of things. So the big thing is make sure you don’t have one person with all the responsibility. Someone who is writing the checks should not be the same person reconciling what’s in the bank account.”

Osbrach’s company helps clients in many ways, from designing systems and helping to implement controls, to unraveling fraud after the fact, including pursuing legal sanctions.

“If you’re designing a system around workflow, especially financial transactions, we can come in and help define the workflow of your system,” he says. “We have a forensics department, which will come in after the fact and do the investigation. We suggest anything from IT controls to business process improvement to best practices.”