What’s Your View of Uber, Airbnb & Other Parts of Hawaii’s “Sharing Economy”?

I’m running late.

My meeting has gone over time by 45 minutes, and suddenly the cushion I allowed for catching the bus out of downtown Honolulu to pick my daughter up from preschool in Moiliili has evaporated. It’s time for me to enter the sharing economy.

I pull out my phone and, instead of calling a cab, I start the Lyft app that’s languished unused for a month. Within 30 seconds, I’m told that Dan (not his real name) is six minutes away and headed my way. Before I see him in person, my phone tells me he looks like a nice young man, his car seems neat and new and other riders have rated him, on average, five stars. Sounds promising.

On Lyft’s app, I watch a GPS icon of Dan’s car approach Bishop Street, make a wrong turn, and circle back in real time. When he arrives, I spot Lyft’s distinctive hot-pink moustache behind Dan’s windshield, and slide into the seat beside someone I’ve never met. Dan is, indeed, a nice young man, who is not employed by Lyft but uses its peer-to-peer ridesharing platform to provide occasional after-work rides as an independent contractor. Soon, we’re talking composting and comparing jobs and, by drop-off, I have not only made it to the school on time, Dan and I have both created some social capital, another benefit of the sharing economy.

The so-called sharing economy came out of nowhere a couple of years ago and suddenly seems to be everywhere, from the peer-to-peer vacation-rental platform Airbnb, which rents thousands of rooms across Hawaii, to UberX and Lyft, competing ridesharing platforms that have taxi companies and regulators scrambling locally and globally. And it’s not only about cars and houses: The things you can share through your smartphone and computer now include clothes (ThredUP), meals (Cookening), power tools (SnapGoods), surfboards (Spinlister) and pets (BorrowMyDoggy).

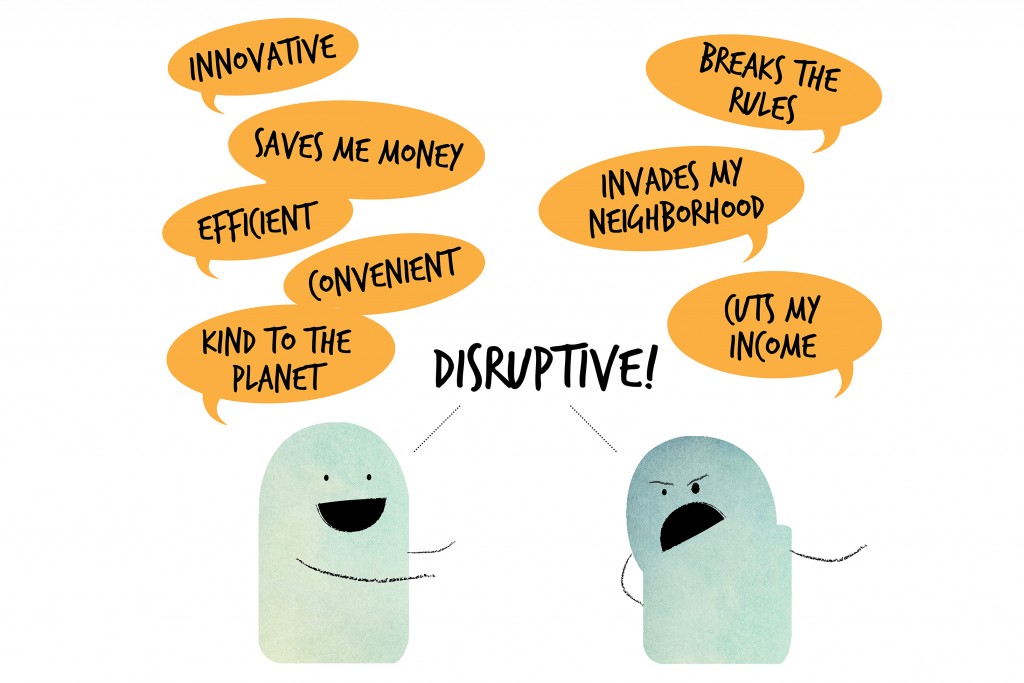

It seems like every day a new sector joins the sharing economy, adding convenience and choices for some people, while disrupting the lives and livelihoods of others. What do these diverse enterprises have in common, and is your industry about to be upended? Here’s a guide to the ever-evolving sharing economy, Hawaii style.

Resource Efficiency

In a nutshell, an enterprise is part of the sharing economy if it tries to distribute existing time or resources more efficiently than traditional economic models (and thereby enhances one or more bottom lines, from financial profit to sustainability to social capital). The sharing economy includes for-profits, nonprofits and ordinary people. For example, when four Hawaii families share the cost and use of one boat for weekend fishing trips and fun outings, it not only reduces the number of boats that need to be produced and purchased, it reduces the storage space needed, and can foster trust and camaraderie among neighbors.

This multiple-user model has been around a long time, but neighborhood ties weakened over recent decades while to-do lists got longer, so the one-owner, one-user model felt like less fuss and less risk.

But a lot has changed lately. The environmental movement emphasizes our planet’s finite resources. The recession of 2008-9 rudely interrupted the borrow-and-spend bubble. And the ubiquity and faster speed of information technology has made sharing easier.

Ryan Ozawa, the Mililani-based co-host of Hawaii Public Radio’s “Bytemarks Café,” explains his personal journey toward shared ownership: “I used to think I wanted to own every piece of music that I listen to.” Then, after LPs gave way to cassettes gave way to CDs gave way to MP3s, he “stopped copying, over time, and started to just use Spotify and other streaming services. Then I realized, I haven’t downloaded a song in ages, because, if I want to hear something, I can hear it. I don’t care where it is. I don’t care who I’m paying or where it comes from. I don’t care that I don’t own it.”

Ryan Ozawa, the Mililani-based co-host of Hawaii Public Radio’s “Bytemarks Café,” explains his personal journey toward shared ownership: “I used to think I wanted to own every piece of music that I listen to.” Then, after LPs gave way to cassettes gave way to CDs gave way to MP3s, he “stopped copying, over time, and started to just use Spotify and other streaming services. Then I realized, I haven’t downloaded a song in ages, because, if I want to hear something, I can hear it. I don’t care where it is. I don’t care who I’m paying or where it comes from. I don’t care that I don’t own it.”

Enabled by Technology

“The Internet changed everything,” says Kailua resident Vern Hinsvark, who has seen the character of his town transformed, first by vacation rental websites such as VRBO.com and now by Airbnb. Between then and now, came social networking, which revamped the concept of an individual’s community and created platforms for online reputations that are instantly accessible by almost anyone. Smartphones equipped users with 24/7 connectivity and an individual GPS. Then the economy crashed, which played its own role in catalyzing the sharing revolution.

Susan Shaheen, co-director of the University of California at Berkeley’s Transportation Sustainability Research Center, pinpoints the year the sharing economy shifted into high gear. “I’ve been very busy since 2010,” she says. “A lot of things have happened in a very short time.”

The user and provider ratings used by apps and other platforms reduced the risk of interacting with strangers and incentivized people to be likeable. Lyft riders are encouraged to sit in the front and treat the driver more as a buddy than a taxi operator. A seamless, automatic payment process enhances the impression that you’re just hanging out together. Even the riders get publicly rated, so there are incentives for everyone to act nicely.

The new ridesharing platforms succeed by giving consumers a more pleasant experience than hailing a traditional cab, says Ozawa. “From the consumer side, getting a car to pick you up now is not calling Frank DeLima and talking to someone who may or may not speak perfect English, and trying to get them to come. You press a button, and the phone does everything, from saying who you are, [proving to the driver] that you’re an eligible customer, and puts a dot where you’re standing, so you don’t have to go, ‘Hi, I’m on Nimitz Highway, but I’m on the Ewa side.’ ”

That instant connection, combined with new mechanisms for creating trust, accountability and interaction between strangers, has led to projects such as TimeBank, a nonprofit platform that lets participants sign up in their local communities to donate and receive labor for all manner of tasks and skill-sharing. Another is the Lending Club, a national peer-to-peer platform that has collectively issued more than $5 billion in loans and has plans for an IPO, with Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs leading the stock sale.

Disruption Affects Us Differently

Another thing modern sharing-economy models have in common is their Silicon Valley-style commitment to disruptive innovation. In the for-profit world, the goal is usually to create a user experience that’s better, quicker, easier and cheaper and, in the nonprofit world, the goal is to increase community and enhance sustainability.

Who doesn’t look forward to that? The disrupted, of course – a category that potentially includes all of us. In certain U.S. cities, taxis have been permitted for decades by a medallion – a piece of regulatory metal whose worth could top $1 million in cities like New York. Though the value of medallions has traditionally outperformed the stock market, their value has fallen in cities where Uber and Lyft are strong. The value of a New York medallion plunged 17 percent from October 2013 to October 2014.

Hawaii doesn’t operate on a medallion system. The state Department of Customer Service says a taxi operator’s license costs just $25 for two years, and an additional business license costs $50 for one year. But the disruption of Uber and Lyft has arrived here, and EcoCab Hawaii owner David Jung is feeling it.

EcoCab’s fleet is driven by employees rather than independent contractors, they emphasize customer service and the cars are hybrids –just the kind of company that sustainability-minded people would normally call. But, says Jung, “Uber and Lyft are so new and so sexy and so well-funded that everyone’s kind of mesmerized by them. It’s human nature, right? When we fall in love with something, we can’t see the warts. They’re right there, but you can’t see them. It’s not until time passes and all the warts start showing.”

It’s not just the riding public that’s in love with Uber and Lyft, Jung adds. He describes conversations he’s had with local policy-makers. “They’ll say, ‘Oh yes, [regulating Uber and Lyft] is something that we need to think about. But I love Uber! I use it all the time!’ ”

“I think the sharing economy is a wonderful thing. I’m all for efficiency, helping the environment, having fewer cars on the road. What upsets me is when the apps use those things as an excuse to bypass regulation that there’s a reason for,” says Jung, citing city regulations that require a physical test for all transportation providers. What of Uber’s claims that it polices the quality of its drivers? “God, I wish people did self-regulate,” says a resigned Jung. “You can’t fight a tidal wave. The tidal wave is coming. You have to wait until it comes, and then recedes back into the ocean.”

It’s not only taxi drivers who are affected by the disruption. Large swathes of the traditional economy are feeling the heat, including lawyers, traditional lenders and even educators, who are competing with MOOCs, “massive open online course” systems such as Coursera, where anyone with online access can take free courses from some of the world’s most prominent universities.

All business sectors are potentially vulnerable to disruption, but Rachel Bosman, a cultural commentator often credited with first identifying the sharing economy in a 2010 TEDx talk, thinks that some are more susceptible than others. In a September 2014 article in the Harvard Business Review, Botsman described five types of vulnerability that make a traditional business open to disruption: “redundancy, broken trust, limited access, waste and complexity.” Botsman writes that existing companies need to “identify where they are most likely to be disrupted” and to “disrupt themselves” if they are to stay competitive.

She identifies banking as particularly vulnerable, writing that the industry is “rife with middlemen and has too many retail branches, both examples of redundancy. Trust in the system is low. Many people have limited access to bank accounts, venture funding and loans. Customers often have untapped value in assets with near-zero interest rates – a form of waste. And complex fees and processes are common.”

P2P or B2C?

The new sharing economy is synonymous with peer-to-peer (p2p) companies like Airbnb, Uber and Lyft. They speak a novel, edgy language of continual iteration, individual empowerment and peer-to-peer community building that can leave older, asset-centralized business-to-consumer (b2c) models looking outdated, slow and un-community-minded.

But what happens when a baby business model grows up? “There are certain periods in time where things start out,” says Shaheen, of UC Berkeley, “and there’s a lot of experimentation. And then it moves into a phase where it’s a lot more about commercialization.”

When you want to access the mainstream, you have to go where the people are, says Joy Waters, a cheerleader for an ideals-based sharing economy and the organizer of ShareFest Honolulu. She says her brother, a businessman, has a very different view of the peer-to-peer side of the sharing economy: “For him, developing all those relationships is like, ‘Oh, my god, kill me now.’ He just wants to pay someone, and not have it be all involved. It’s simpler. And I get that.”

Marry that mainstream desire for frictionless transaction with an existing business-to-consumer company that is also looking for ways to evolve, and you might get something like Enterprise CarShare.

A few minutes’ walk from my desk on Bishop Street, there’s a streetside nook of Mark’s Garage with a sleek silver Nissan Versa tucked into it. A card waved over a sensor attached to the windshield changes the light from red to green and I’m in. I retrieve the keys stashed in the glove compartment and pull into traffic on Nuuanu Avenue. It’s so seamless and interaction-free that it feels a little like theft. It’s actually a business-to-consumer sharing-economy model at work.

But how can for-profit, b2c models be part of the sharing economy if the peer-to-peer interaction is missing? Shaheen emphasizes that what’s being shared is “access to goods and services.” She acknowledges there is a “line in the sand” between p2p and b2c asset-sharing systems, but says both play a part in the sharing economy: “I don’t distinguish between those two models. I’m studying the phenomenon of shared access to mobility and, if it’s a b2c model, to me that’s sharing just as much as a person putting their own private vehicle into sharing.”

Enterprise CarShare spokes-woman Laura Bryant agrees. She says Enterprise came up with the idea of a community-based car-sharing model decades ago. Enterprise CarShare, which launched recently in downtown Honolulu, checks all the boxes of a sharing economy business, says Bryant. “Let’s say you’re a person who has a small car, but you need a bigger vehicle on the weekends because you’re taking your kids to ball games, you’re making trips to Home Depot. You don’t have to have both of those cars parked in your garage. You can rent one.”

Many b2c asset-sharing models actually predate the p2p superstars of today – like Hawaiian Rent-All, with its decades-old theater marquee sign at Beretania and McCully. And traditional b2c retailer Patagonia has sharing-economy concepts built into its marketing DNA, with a highly effective “Don’t buy this jacket” campaign that encourages users to buy secondhand, emphasizing the quality and longevity of its products in the process.

As existing companies disrupt themselves, increasing access and shedding complexity and waste to stay current, the b2c model is also one of the most interesting to watch. Shaheen says it’s playing out across the transport sector of the sharing economy, where b2c has become a major player.

Nonprofits: The Utopian Version

As the for-profit side of the sharing economy matures into multi-billion-dollar valuations and infiltrates existing b2c models, the nonprofit side of the sharing economy is also gaining traction. It’s out in full force at Honolulu’s first ShareFest, a daylong celebration of what the online resource hub Shareable calls the “sharing revolution.” Shareable’s philanthropic mission is to make sure that the nonfinancial benefits of the sharing economy – resource sustainability, individual empowerment, the building of interpersonal community and trust – don’t get thrown under the bus as aspects of the sharing economy go mainstream and big money.

At Honolulu’s version of ShareFest, Shareable’s global city-by-city event, it’s clear that the sharing economy has created some interesting bedfellows. Live Hindu music from a circle of singers fills the air. Under the shade of a monkeypod tree, people have left potluck offerings for anyone who’s hungry. There are free massages, a book-swap table and a sewing collective devoted to helping you transform old clothes into new wearables. BoxJelly, the Honolulu co-working space, is also there, teaching passersby how to code. The City and County’s Neighborhood Commission Office has a table, where Noelle Besa Wright warmly greets Ben Trevino, who’s about to become BikeShare Hawaii’s president and COO.

Lindsea Wilbur, a research affiliate with the Palo Alto-based think tank Institute for the Future, is here, too. “The cool thing about the sharing economy,” she tells me, “is the social and cultural capital that comes along with it.” It’s a message she thinks Hawaii is primed to hear because it’s an island-based culture already keenly aware of finite resources and used to considering multiple bottom lines. “The typical model is, you buy it, you use it, you throw it away. We have these resources here (in Hawaii). What are the ways we can conserve them?”

Tom Llewellyn, the network coordinator for Shareable’s international Sharing Cities Network, stresses that interpersonal bonds are a form of currency that “money can’t buy,” adding that the “sharing economy is about shifting values, to take care of the resources, financial, social or environmental, that we’ve got.”

Ryan Ozawa agrees that nonprofits might help perpetuate the sharing economy’s nonfinancial benefits. “Everybody can see the utopian ideal. The sharing economy might be the way forward for humankind, but it might or might not be monetizable” in the long run, says Ozawa. “What I want to see is nonprofits becoming the stewards of the sharing economy. Like the Nature Conservancy – for them, making money isn’t their prime motivator. They’re interested in sustainability; their objective is helping people, reducing waste. Why can’t Hawaii nonprofits become the champions of the sharing economy?”

Says Waters, “There’s that quote, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.’ And the truth is both are true right now, and we have a choice in which part we play.”

Airbnb: Disruption Comes to Your Neighborhood

It’s received wisdom that the sharing economy is great for the new players and for consumers, but not for established businesses operating under older models. And that can make all the talk about the importance of upholding existing regulations sound uptight and uncool. But what about when the sharing economy begins to affect bystanders? What happens, for instance, when it changes the neighborhood where you live?

Ten years ago, Kailua felt like a well-kept secret, a friendly, sleepy bedroom community right next to some of Oahu’s best beaches. Then three factors helped the world discover Kailua: Tourists now want to “live like a local,” the Internet globally broadcasts the word about “secret” destinations like Kailua and a U.S. president takes his Christmas vacations there. Within the last decade, Kailua has become a place of tour buses, Segway tours, kayak rentals, tourist boutiques, traffic jams – and unpermitted short-term vacation rentals. The online vacation-rental platform Airbnb lists at least 259 rentals just in the Kailua area, from a $65-a-night bedroom with a covered lanai and private bathroom to an immaculately decorated four-bedroom home near the beach, with a lava-rock fireplace and a pool, for $1,275 a night. VRBO, Airbnb’s web-based predecessor, shows even more listings for Kailua: 329.

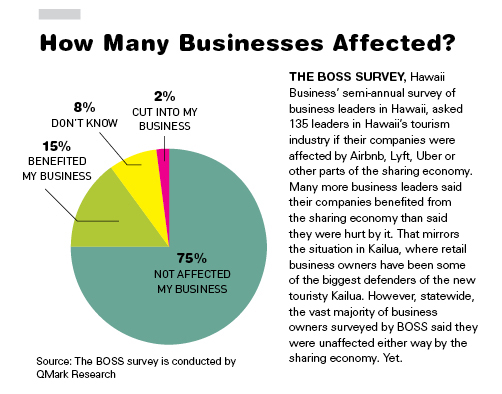

Visitors are everywhere, not just at the beach, but at grocery stores and coffee shops. They throng the boutiques and restaurants that have sprung up or expanded to meet burgeoning visitor demand. It’s great for businesses, many of which now depend on tourist dollars. But there’s no denying that Kailua has changed.

Vern Hinsvark remembers a quieter Kailua. In 1989, he and his wife moved into the house she grew up in, on a little lane of 11 houses that ends at the beach. There’s always sand on the road.

On Hinsvark’s street, he says, five of the 11 houses contain one or more vacation rental units; only one has a permit. No new permits for short-term vacation rentals in Kailua have been issued since 1990. Hinsvark is a member of the Kailua Neighborhood Board, which has been very vocal about the need to enforce existing regulations. Those rules require that unpermitted vacation rentals be long term, i.e. 30 days or more.

Annette lives less than a quarter-mile from Hinsvark, as the crow flies. The 62-year-old grew up in Kailua and she, too, lives steps from the beach, a location highly valued by visitors and residents alike.

Annette (not her real name) figures that 60 percent of the houses on her street contain vacation rentals. Her property has two, both unpermitted, both advertised on Airbnb. In one sense, Annette exemplifies the ideals of the sharing economy. Her Airbnb reviews enthuse that she is “the perfect host” and gush that booking with her was “the best decision of our Hawaii trip.” Annette enthusiastically helps guests make reservations and arrangements, offers books and advice, and recommends places she loves.

If you’re her guest and she likes you, she’ll invite you in for a glass of wine, or even dinner: “If I have it and I’ve got it going on, I’ll share whatever I have,” she says, describing how she offered recent non-English-speaking guests bowls of her homemade Portuguese bean soup to help them feel at home in Hawaii. “How neat it is to eat food from the people of the country that you’re visiting! I love that. That’s what makes it personal.”

You won’t get that in a hotel, and that’s often the feeling visitors really want – true hospitality, exchange of money or not. “I’ve got to say, the best thing about this is that you meet people and they’re so happy to be here. Every day, they’re just thrilled,” Annette says. She clearly has been a good ambassador for our state, which translates into great visitor impressions, lots of cross-cultural social capital created and many visitor dollars spent.

The catch? Sometimes, the creation of cross-cultural social capital comes at the expense of local community capital. Sometimes that capital is literal: Annette says she pays the 9.25 percent Hawaii Transient Accommodations Tax, but not everyone does. Airbnb does not require those tax payments in Hawaii, though it does collect taxes in some other places.

Both Hinsvark and Annette agree that the pace of change in Kailua has increased exponentially in the last few years, and both name Airbnb as a significant catalyst – not for the change itself, which has many causes, but for the pace of change.

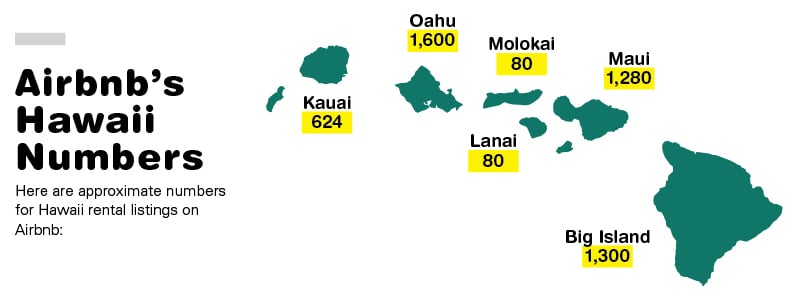

Airbnb has become a big player in Hawaii’s tourism industry, but it’s difficult to determine how big. The Hawaii Tourism Authority counted 65,296 hotel rooms, condo hotels, and timeshares throughout the state in 2013. HTA also observed that the number of IVUs (individual visitor units) it was able to count rose more than 500 percent from 2004 to 2011. HTA counted 6,943 IVUs in 2013 – equal to 10 percent of Hawaii’s traditional visitor accommodations – but HTA admits that is “likely a significant under-estimate.”

A non-conservative estimate puts that percentage closer to 50 percent. George Szigeti, president and CEO of the Hawaii Lodging and Tourism Association, says good sources suggest there may be as many as 25,000 to 30,000 IVUs throughout the state.

Since many IVUs do not collect or pay the hotel room tax, that adds up to a lot of lost tax revenue – money that partly goes back into funding the infrastructure and marketing campaigns that attract visitors to Hawaii in the first place, Szigeti says. “We really believe that if (IVUs) are what visitors want, then that’s fine. All we ask is a level playing field. Just pay your fair share,” he says.

Annette has been doing vacation rentals since 2002 and has been advertising on Airbnb since 2012. “I would say in the last four years, it’s really exploded,” she says. She adds that the density of Airbnb rentals has increased to the point where “I go on there, and I see more and more people are (joining) it. Sometimes I’ll even recognize them – Oh, I know that person!” She shows me the Airbnb entry of a friend she’s inspired to convert and advertise a studio, and describes guests of hers who have become Airbnb hosts themselves. She views the near future from a provider’s perspective: “I think the competition is going to be a lot stiffer. That’s why I really need to be on my toes.”

On Hinsvark’s street, not only are half of the houses sometimes or always operating as short-term rentals, but another is currently being converted. Annette provides off-street parking for all her guests, but not all vacation rentals do, and even she has had her share of drunken antics and marijuana buys. (She says she told one group it “wasn’t cool,” and they apologized.)

Both Hinsvark and Annette say that visitors usually mean well, but they’re often in party mode. Whatever mode they’re in, says Hinsvark, they are often not in sync with residents. “People come in and they’re from Germany, so they’re 12 hours off and they’re making noise in the middle of the night,” he says. Sometimes the garbage truck can’t get down his street for all the parked cars.

“The only way Kailua got to be where it is, is because of these illegal vacation rentals,” he says. “If you go back five or six years, and you look at the people that live in Kailua, there were just not very many people here. It was a bedroom community.” Now, seven days a week, it’s clear Kailua has become a teeming tourist town.

Last year, the Kailua Neighborhood Board asked the Hawaii Tourism Authority to stop promoting short-term rentals in Kailua as a “peaceful alternative to lively Waikiki” on their website. HTA declined to do so, but released a statement that said it did not support illegal rentals. The Associated Press gave the disagreement national coverage, with the headline, “Hawaii Residents Don’t Want the Sharing Economy in Their Town.”

Hinsvark understands the attraction for visitors. “If I go on a trip,” he says, “I would probably use Airbnb, too. It’s not Airbnb’s problem. It’s the community’s problem. … I think it’s up to the cities to license and control.”

Ryan Ozawa says the problem is that regulation and enforcement move at a human speed and with due process, while online platforms move at the speed of data and disruption – and Airbnb’s instant-access, seamless 24-hour platform is “like a tidal wave to deal with, as far as regulation is concerned.” Szigeti agrees. Speaking about the staggering valuations of many new sharing economy platforms like Uber, which was recently valued at $40 billion, he says: “If you’re worth $40 billion, you have some muscle behind you to protect your (business) model. They’re not going to be just run over because of the Legislature.”

Every U.S. city with lots of tourists faces the question of whether to go with the tidal wave and legalize short-term vacation rentals. When Portland’s city council voted unanimously to allow short-term rentals in June 2014, news outlets covered it with a telling shorthand: “Portland legalizes Airbnb.” That legalization came with regulations: residents needed to pass a minimal safety inspection and obtain a $180 permit. Residency in the unit for at least nine months of the year was also required, and Airbnb has stepped in to collect lodging tax and pass it on to Portland.

San Francisco followed suit in October 2014, with its Board of Supervisors voting 7-4 to legalize short-term rentals with a few restrictions, and Airbnb is collecting the taxes. Airbnb representative Marie Aberger stopped short of saying the company would do the same for Honolulu if short-term rentals were legalized here, saying only that they would “take the lessons we learn (in Portland and San Francisco) and move forward.”

Meanwhile, in New York City, Attorney General Eric Schneiderman is engaged in what is often described as a “war” with Airbnb. In October, his office released a report that Slate.com financial blogger Alison Griswold described as showing Airbnb rentals, almost three quarters of which are illegal, “gobbling up” lower Manhattan.

Hinsvark knows you can’t put the genie back in the bottle. He knows that many of Kailua’s businesses now depend on, and advocate strongly for, a 24-hour tourist presence, which creates huge incentives for potential Airbnb hosts. “There’s no one enforcing the rules,” he says, offering up Haleiwa, another town that has transformed in the last decade, as a cautionary tale. “I don’t want to go to the North Shore now (because of the traffic). … Kailua’s getting the same way, and it just calls up the question: ‘How many people can we handle?’”

Sharing-Economy Terms You Should Know

The sharing economy seems to be the catch-all term for a wide range of models, says Susan Shaheen. But, terms are splintering off, each emphasizing a different facet of the sharing economy.

Collaborative consumption highlights “access over ownership” models where many people share single objects or data files. For video, that includes Netflix and Hulu; for music, think Spotify and Pandora; for cars, it includes Enterprise CarShare. Hawaiian Rent-All and your local library also qualify.

The terms peer economy or peer-to-peer economy conjure visions of economic and community relationships among individual equals. This term includes all p2p platforms, from CouchSurfing (like Airbnb, but free) to Lending Club. What’s not included in the peer economy: b2c models, even those that practice collaborative consumption.

When the gig economy or the 1099 economy (referring to the IRS’s tax form for independent contractors) is mentioned in conjunction with the sharing economy, it’s a way to highlight that much of the sharing economy’s for-profit sector consists of p2p platforms that function as middlemen between users and independent contractors, who own the assets and assume all the risk. The gig economy, though, is bigger than the sharing economy, referring to a national shift toward contract and part-time work in sectors that range from university teaching to photography to manufacturing. It’s up to you whether you see this development as empowering to the thousands of “microentrepreneurs” or an alarming trend that often drives real incomes below minimum wage and removes the stability of a steady paycheck and benefits.

The collaborative economy is a version of the “sharing economy” that Rachel Botsman, one of the sharing economy’s most prominent proponents, uses to leave behind the hippie connotations associated with the word “sharing.” The collaborative economy encompasses the sharing economy’s for-profit sector and you may see this term grow in popularity as for-profit p2p models grow in size, b2c models evolve and people shy away from the cuddly word “sharing” because it seems less and less appropriate.

Virtue is big business these days, giving rise to the accusation of sharewashing. As the sharing economy matures, the number of businesses hoping to take shelter under the sharing umbrella without necessarily subscribing to its community-building or resource-sharing goals has increased. The term sharewashing was inspired by greenwashing, the accusation that a business seems more environmentally sustainable than it actually is, which, in turn, came from whitewashing.

Ways to Join the Sharing Economy

There are lots of sharing-economy ideas that haven’t made it to Hawaii, like Parking Panda, the Airbnb of parking spaces, and TaskRabbit, one of many online p2p platforms for services. But there are still plenty to choose from.

For budding capitalists: Lending Club. You can lend money for a larger return than you get from a bank – which is still a lower rate for borrowers than most credit card companies and banks charge. The p2p financial platform Lending Club exploits that gap and puts individual lenders in touch with individual borrowers. Lender beware: With higher potential returns comes heightened risk.

For freelancers and independent contractors: BoxJelly. Share your space and, in the process, your mind. Relationships are formed at BoxJelly, a co-working space where you can reserve your own desk on a monthly basis, hold meetings and events, or drop in when you need a desk (or a couch) and a friendly face.

For fashionistas: Rent the Runway. Everybody who buys anything online in Hawaii knows that shipping can be a problem. Unlike other collaborative clothing consumption companies, Rent the Runway does ship to Honolulu, and it offers an array of designer dresses and accessories for a fraction of the price of ownership. You order it, the company sends it to you clean, and you send it back after wearing it. If you’re the type who likes to stay on the cutting edge of wearables, this one’s for you.

For community-builders: Oahu Timebank. The .org in its URL gives it away: Timebanks USA, which has chapters across the nation, trades in time, not money. Operating under the assumption that “we each have something to offer,” Oahu Timebank asks its users to post a list of skills and areas in which they’re willing to help, and another list of areas in which they could use a hand. The idea, on a local scale, is to join “untapped capacity to unmet needs” in an era when you might not know your neighbor, creating a platform where every member has declared he or she is willing to help. Trade car washing for pet sitting, or get a lesson in making awesome cocktails in exchange for help assembling furniture.

For travelers: Airbnb. We’re not advocating illegal vacation rentals, but Airbnb and its Web-based ancestor, VRBO (vrbo.com), often offer less expensive (if less guaranteed) accommodations than hotels. As always, travel at your own risk. Variation for those who want to find a well-rated dogsitter while traveling: DogVacay. There’s also Cookening, which hooks up travelers with home-cooked meals and company around the world, for a fee.

For riders: Lyft and Uber. These “ride-sharing” services are often mentioned in the same breath, but they operate on different business models. Lyft (the one with the pink moustache on every car) is standing by its “your friend with a car” motto, asking riders to sit in the front seat and treat drivers more as friends. Uber, meanwhile, seems set on world domination, as reflected in its Nietzschean name and its current valuation: $40 billion vs. Lyft’s $700 million.

UberX, the p2p ride-sharing service, is just one aspect of a company that has piloted several other services and is very public about its desire to eventually replace its drivers with self-driving cars. For both services, which landed in Honolulu this summer, you download the company’s app, choose an available driver based on reviews and location, provide your credit card number, and then rate your driver after the fact, while your drivers rate you, too. No cash is exchanged; it’s all done through an app on your smartphone.