What’s Next for OHA

The organization serves thousands of Native Hawaiians each year, but its scandals, infighting and negative image often overshadow its good work. Here’s a look inside OHA and how its problems are being addressed.

For 16 years the staff of nonprofit Awaiaulu has been working to identify, translate, transcribe and digitize Hawaiian language media. To expand its projects, Awaiaulu received a two-year, $353,600 grant in fiscal year 2018 from the Office of Hawaiian Affairs.

Awaiaulu’s executive director, Puakea Nogelmeier, says OHA’s funding to revitalize olelo Hawaii in all mediums “has made it possible to provide access to our work and historical materials that would otherwise not have been accessible to Hawaiians and the general public.”

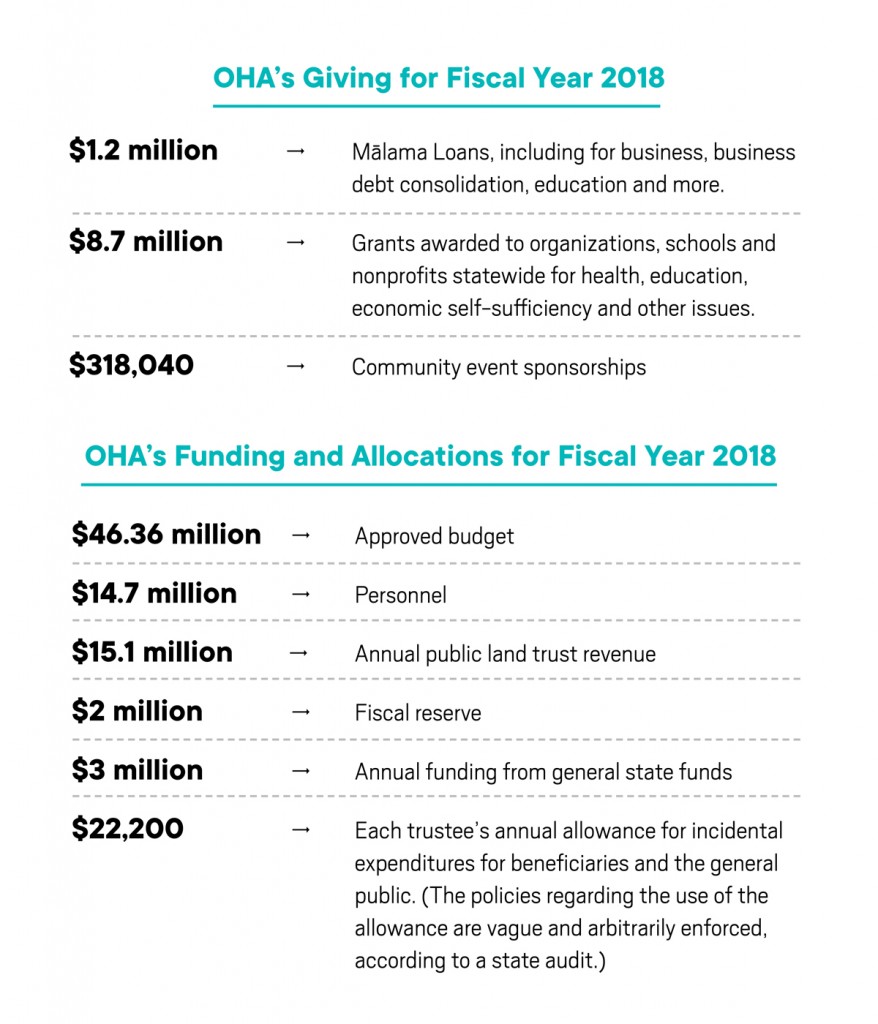

OHA funded $8.75 million in competitive grants in fiscal year 2018 to dozens of organizations across the Islands, but those checks rarely made news. Like most public agencies, OHA – a semiautonomous government agency – usually only makes the news when something bad happens. And it has been in the news a lot during the past two years: infighting, lawsuits, critical state audits and an investigation by the state Department of the Attorney General and the FBI.

The Office of Hawaiian Affairs was created in 1978 at the state constitutional convention. This was during the height of the Hawaiian Renaissance, the movement that revived Hawaiian cultural practices, art and language and was a political response to local and national events like the Navy’s bombing of Kahoolawe and the Vietnam War.

Its semiautonomous foundation has always been complex. OHA is independent from the governor’s office and other state departments. But the state controls much of the organization’s finances via annual general funding and revenue from the state’s public land trust. (See sidebar on page 63.) Its broad mission to better the conditions of Native Hawaiians covers everything from establishing self-governance to helping improve education, health and economic self-sufficiency and protecting the land.

This year, its 41st, OHA is organizing its strategic plan for the next 10 to 12 years around those goals. OHA’s major achievements over the years include providing $21.6 million in funding to Hawaiian-focused public charter schools since 2005, the 30-acre conveyance from the state to OHA of Kakaako Makai in 2012 and becoming one of four co-trustees of Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument in 2017.

OHA has ardent supporters but its future planning and past good works tend to be overshadowed by controversy. Those who work there are aware of its reputation, and many acknowledge that perception is reality inside OHA. Here’s an in-depth look at the organization, what’s troubling it and how these problems are being addressed.

Internal Relationships Affect the Outside Community

If OHA were an ahupuaa, its CEO and board of trustees comprise the land and the sea – essential elements to the traditional land division. As with any organization, a cohesive union between the top executive and the board is crucial to the success of OHA, its operations and the morale of its roughly 170 employees. This relationship is also a bellwether to many

in the community of how OHA is doing as

an organization.

“Until (we) can do the fundamentals, clean up and get the momentum to build, it’ll be very hard to change anybody’s perspective of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs,” says Colette Machado, chair of the board of trustees. Six framed certificates hang in her office, representing one for each of her four-year terms as trustee since 1996. Representing Molokai and Lāna‘i, Machado has served with three different CEOs and numerous board iterations.

OHA is governed by a board of nine trustees who are elected in a statewide, public campaign open to all candidates and all voters, not just Hawaiians, and hold four-year terms. Their general duties include overseeing OHA’s trust, valued at $600 million, and approving its budget. Perhaps their most high-profile job is hiring the organization’s CEO. Throughout OHA’s 41-year history, the relationship between the board and the CEO has ebbed and flowed, depending on who is in office and their respective agendas.

Beginning in 2016, the board’s affairs were particularly dramatic. At least four lawsuits involving trustees were filed, including trustees suing each other. At least two serious attempts to oust Kamanaopono Crabbe as CEO were made but the efforts failed to get the required votes of six trustees. Longtime trustee Rowena Akana was forced out as chair by her colleagues after only about two months. Two critical audits were released in February 2018. And two state Ethics Commission complaints charged former trustees Peter Apo and Akana with ethics violations and imposed fines of $25,000 and $23,000, respectively.

There have also been times of harmony. Local newspapers had generally positive coverage of Randall Ogata, who served as CEO from 1997 to 2001, and his working relationship with former board chair Clayton Hee. Clyde Namuo, who was CEO from 2001 to 2011, says he also worked well with former board chair Haunani Apoliona. “The chair and I had a very good relationship; I would always let her know what was going on,” says Namuo, who currently works at the Polynesian Voyaging Society. “We would try to accommodate as much of what the trustees needed, especially if I felt that what they were asking for was reasonable.”

There have also been times of harmony. Local newspapers had generally positive coverage of Randall Ogata, who served as CEO from 1997 to 2001, and his working relationship with former board chair Clayton Hee. Clyde Namuo, who was CEO from 2001 to 2011, says he also worked well with former board chair Haunani Apoliona. “The chair and I had a very good relationship; I would always let her know what was going on,” says Namuo, who currently works at the Polynesian Voyaging Society. “We would try to accommodate as much of what the trustees needed, especially if I felt that what they were asking for was reasonable.”

Crabbe says any discord between the board and the executive team, particularly the CEO, distracts OHA staff and can spill out into the community. He describes his tenure since 2012 with the board as seasonal. “It depends on the leadership. It depends on a real understanding of clarity of the roles and responsibilities of board trustees … and what’s in the best interest of the organization and understanding what truly is our fiduciary duties to the organization, to our community, to the broader public,” he says.

Trying to Make Fixes

Right now, the outlook is bright: Both Crabbe and Machado say they have an amicable working relationship. “I think it’s much improved from the past two years. It’s more positive and hopeful,” Crabbe says, adding that he and Machado meet in person about every week.

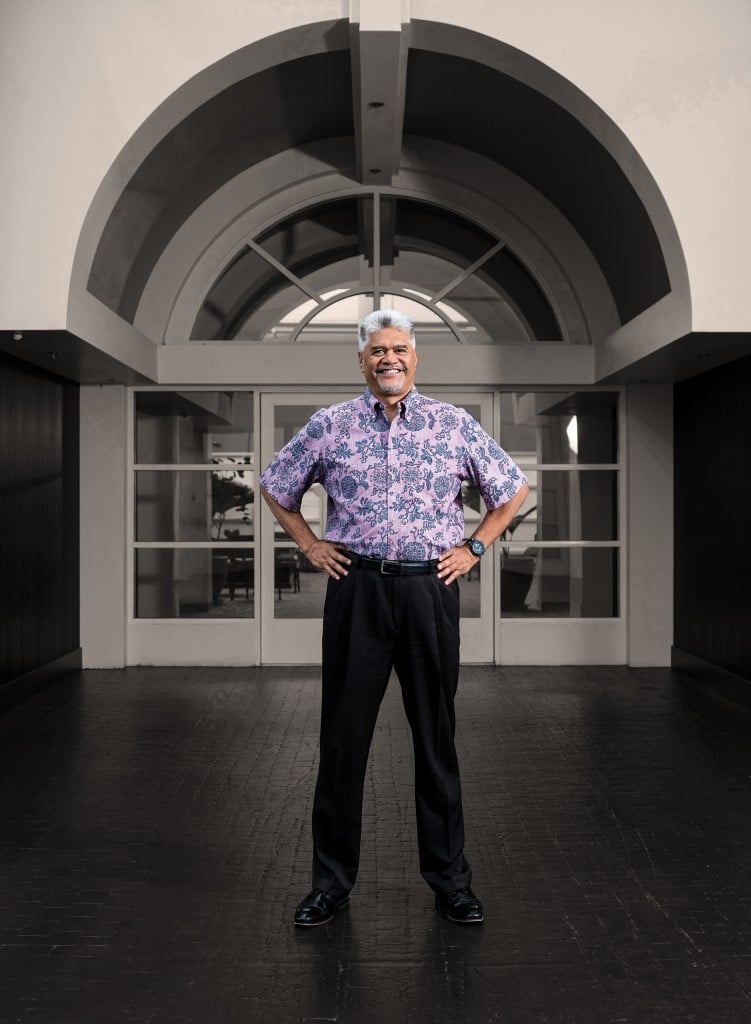

Crabbe was appointed by the board as CEO in 2012, after first joining OHA in 2009 as its research director. Affectionately known as KP by his staff, Crabbe came to the organization from the Waianae Coast Comprehensive Health Center, where he was the director of psychology training. He first butted heads with the board in 2014, when he requested then-U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry’s opinion on whether the Hawaiian Kingdom exists as an independent sovereign state.

Trustee-at-large Kelii Akina says, “I have critical concerns about the effectiveness of (OHA’s) administration.” | Photo: Aaron Yoshino

In 2016, longtime former trustee Akana became chair. She pushed to remove Crabbe as CEO, including filing a lawsuit against fellow trustees challenging the legitimacy of his contract. The move created a fissure between those who supported Crabbe and those who didn’t. “It dragged out and dragged out,” says Machado, who was a Crabbe supporter.

Akana is no longer on the OHA board, but at least one trustee remains dissatisfied with Crabbe’s job performance as CEO and the organization’s fiduciary management. “I have critical concerns about the effectiveness of the administration,” says trustee-at-large Kelii Akina. “In fact, when I became a trustee in 2016, I articulated those concerns and they remain. I ran for OHA on the platform of being a watchdog.”

Akina, who is also the president and CEO of the nonprofit conservative advocacy group, Grassroot Institute of Hawaii, says one of his main priorities is scrutinizing OHA’s fiscal practices. His first goal was to have OHA and its LLCs independently audited. “The greatest problem facing the Office of Hawaiian Affairs today is its reputation,” he says. “The improvement of reputation ultimately depends on regaining credibility. To regain credibility, we have to take a hard look at our financial condition.” For the past two years, as trustee, Akina has been advocating for OHA to reduce discretionary spending and institute a budget and finance committee for the board of trustees.

This year may be Crabbe’s last year as CEO; his contract expires this summer. Machado says the board is working with a firm to jump-start the application process for the next CEO. Crabbe says he’s discussing his options with his attorney as to whether he will apply again. “It will also depend on how much the current board leadership addresses inherent governance matters and provides concrete action steps to address them,” he says.

While Crabbe’s future at OHA remains uncertain, the board is embracing a more united front as it evaluates the CEO position and examines the organization’s upcoming strategic plan. In December, the trustees voted unanimously to elect Machado as chair. The November 2018 election also marked the first time in four years that two new trustees were elected to OHA: Kalei Akaka and Brendon Lee. The board has restructured its committees on resource management and on beneficiary advocacy and empowerment.

Machado says it feels like the board is turning a corner. “We’ve actually overcome some of the biggest, more embarrassing moments,” she says. “So that’s important for people to see that we’re doing the best we can and that it’s getting cleaned up in a manner that’s transparent.”

Fiscal Responsibilities

Last February, the state auditor’s office released two critical audits of the organization, stating, “OHA has spent with little restraint.” The reports made local and even national news.

Soon after, OHA published op-eds in the Honolulu Star-Advertiser and in OHA’s monthly newspaper, Ka Wai Ola, written by Machado to share the organization’s side. “OHA’s funding absolutely goes toward bettering the lives of Native Hawaiians,” she wrote.

The problem facing OHA and its fiscal reputation is usually not who the organization spends its funds on, but rather how. The main state audit found:

- In fiscal years 2015 and 2016, OHA spent nearly twice as much – $14 million total – in discretionary disbursements than it spent in funding through competitive grants, which was $7.7 million total. This discretionary funding is approved by both the board and the executive team.

- The fiscal reserve, which according to 2003 guidelines was designed to provide emergency funding, plunged from $23 million in 2006 to $2 million in 2016 as the board withdrew the maximum $3 million allowed each year.

- The trustee’s annual allowance of $22,200 each was used by some trustees for “many instances of questionable spending,” including $1,500 in attorney’s fees, a $3,000 donation to the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., and $209 for installation of a home security system. (The audit didn’t name the trustees with these examples of questionable spending and OHA would not disclose that information.)

- Crabbe ignored “do not fund” recommendations for the CEO sponsorship grant program. He also had the authority to move funds without board approval, even when program funds were exhausted. In fiscal year 2016, the CEO sponsorship budget was $100,000, but $210,700 in grants were awarded.

Machado doesn’t dispute that OHA needs to tighten some of its policies and procedures in light of the state audits, both to help improve the organization’s overall financial health and to restore the community’s faith that OHA is meeting its fiduciary duties. “We’ve been working behind the scenes very hard to complete those kinds of tasks that were directed to us,” she says, taking a black day planner from her desk. Inside, she has Tuesday, May 7, highlighted. It marks the 90th day since she was re-elected as chair. It’s also the deadline she set for herself to correct issues raised in the two state audits.

The board already placed a moratorium on the use of the fiscal reserve and the distribution of the annual $22,200 allowance to trustees. (The release of the critical audit was sandwiched between the high-profile investigations of Apo and Akana, the two former trustees found guilty of abusing OHA’s resources.) The board limited Crabbe’s authority to make operating budget expenditure adjustments without the board’s approval to amounts of $100,000 or less. The board also approved new guidelines for discretionary spending.

Crabbe says the state audit’s findings weren’t unexpected. In 2016, the board approved a fiscal sustainability plan, an initiative he spearheaded to increase the value of OHA’s assets, such as Kakaako Makai, which it acquired in 2012. (The land remains undeveloped.) In preparation, the organization hired the accounting and financial analysis firm, Spire Hawaii.

“(The audit) wasn’t surprising because a lot of the work that was built up by Spire was hopefully to put these things in place to demonstrate we knew about some of our spending patterns,” he says. “Mostly it was by the board and that we were going to take corrective action. Spire came to the table a number of times in 2017 to forewarn trustees and administration.”

The auditor’s office had criticized OHA before the two 2018 reports. Namuo began at OHA not long after the organization had received fault-finding audits, including criticism of the use of discretionary funds and trustee allowances. “It was always a little bit of push and pull with the trustees because there were times where we would say, well, you know, that’s just not appropriate,” he says. “The general guideline I think people thought was appropriate was that as long as it satisfied the mission of OHA, which was to work for the betterment of Native Hawaiians, it was OK.”

In December, the OHA trustees voted unanimously to elect Colette Machado as the chair of the board of trustees. “(It’s) important for people to see that we’re doing the best we can and that it’s getting cleaned up in a manner that’s transparent,” she says. | Photo: Courtesy of Office of Hawaiian Affairs

OHA’s finances are also being investigated by the state attorney general and the FBI. “We’ve been a cooperating partner,” says Machado of the investigation. Krishna Jayaram, special assistant to the state attorney general, declined to comment on the scope or status of its investigation. The FBI also has not discussed its investigation publicly.

“There’s substantial information they wanted that we submitted to the AG’s office,” says Machado. She says the organization sent the office a “tremendous” number of documents, including check ledgers and information on grants and solicitation of vendors. Machado says to her knowledge, no one from the organization has been subpoenaed.

“I have not been personally involved nor presently impacted by the investigation,” Crabbe says.

For the first time, OHA is also conducting an independent audit of itself. OHA is paying audit firm CliftonLarsonAllen $500,000 to audit the organization and its LLCs to identify potential areas of fiscal waste, fraud and abuse. The audit’s main proponent is trustee Kelii Akina. But he says he’s not sure if the audit firm has even received the documentation it needs to complete the audit and believes it’s due to stalling within OHA. He declined to say who, though, or why. “The length of time that it’s taken is simply not appropriate to the urgency of the audit,” he says. Machado and Crabbe both say the organization is cooperating, but neither predicted when the audit will be completed.

Reversing the Negative Reputation

The infighting, audits, investigations and ethics violations have tarnished OHA’s reputation. “It’s been a dark cloud over the organization,” says Crabbe of the turmoil.

But he and Machado say OHA is still fulfilling its mission to better the lives of Native Hawaiians. Last year, nearly 100 organizations across the Islands, from hula halau and a canoe racing association to charter schools, health care clinics and housing programs received competitive OHA grant funding that supported thousands of women, men and children.

Kamanaopono Crabbe, shown at OHA’s headquarters on Nimitz Highway, has been OHA’s CEO since 2012 but it is not clear if his contract will be renewed this summer. it is not clear if he will stay on. | Photo: David Croxford

“Many good things have come out of or through OHA,” says Awaiaulu’s Nogelmeier. The UH professor emeritus of Hawaiian language says OHA’s Papakilo database of 58,600 digitized Hawaiian language newspapers, letters, genealogy indexes, archeological reports and more has been particularly impactful.

Jon Osorio, dean of UH’s Hawaiinuiakea School of Hawaiian Knowledge, says OHA has also been a good advocate in protecting – or fighting to protect – cultural spaces and artifacts, such as Mauna Kea and Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument. “It’s something that I think if there were no Office of Hawaiian Affairs, we would have almost no ally in these cultural protection fights,” he says. “Frankly OHA is it.”

Legislators have consulted with the organization. “We turn to OHA when issues relating to Hawaiians come up,” says state Sen. Maile Shimabukuro. She says those include cultural practices, incorporating Hawaiian language, education and the environment. Shimabukuro serves as chair of the Senate’s Hawaiian Affairs Committee and her district covering Nanakuli, Maili, Waianae, Makaha and Makua has Oahu’s largest population of Native Hawaiians.

Legislators have consulted with the organization. “We turn to OHA when issues relating to Hawaiians come up,” says state Sen. Maile Shimabukuro. She says those include cultural practices, incorporating Hawaiian language, education and the environment. Shimabukuro serves as chair of the Senate’s Hawaiian Affairs Committee and her district covering Nanakuli, Maili, Waianae, Makaha and Makua has Oahu’s largest population of Native Hawaiians.

Grant-making and advocacy are the heart of the Office of Hawaiian of Affairs and why it was established 41 years ago. As OHA finalizes its strategic plan for the next 10 to 12 years and tries to rectify its discrepancies, OHA leaders will look to these examples of goodwill.

“I think people expect and demand better of us,” says Crabbe. “And they should, among Hawaiians ourselves, and I think even non-Hawaiians.”

The Fight for Public Land Trust Revenues

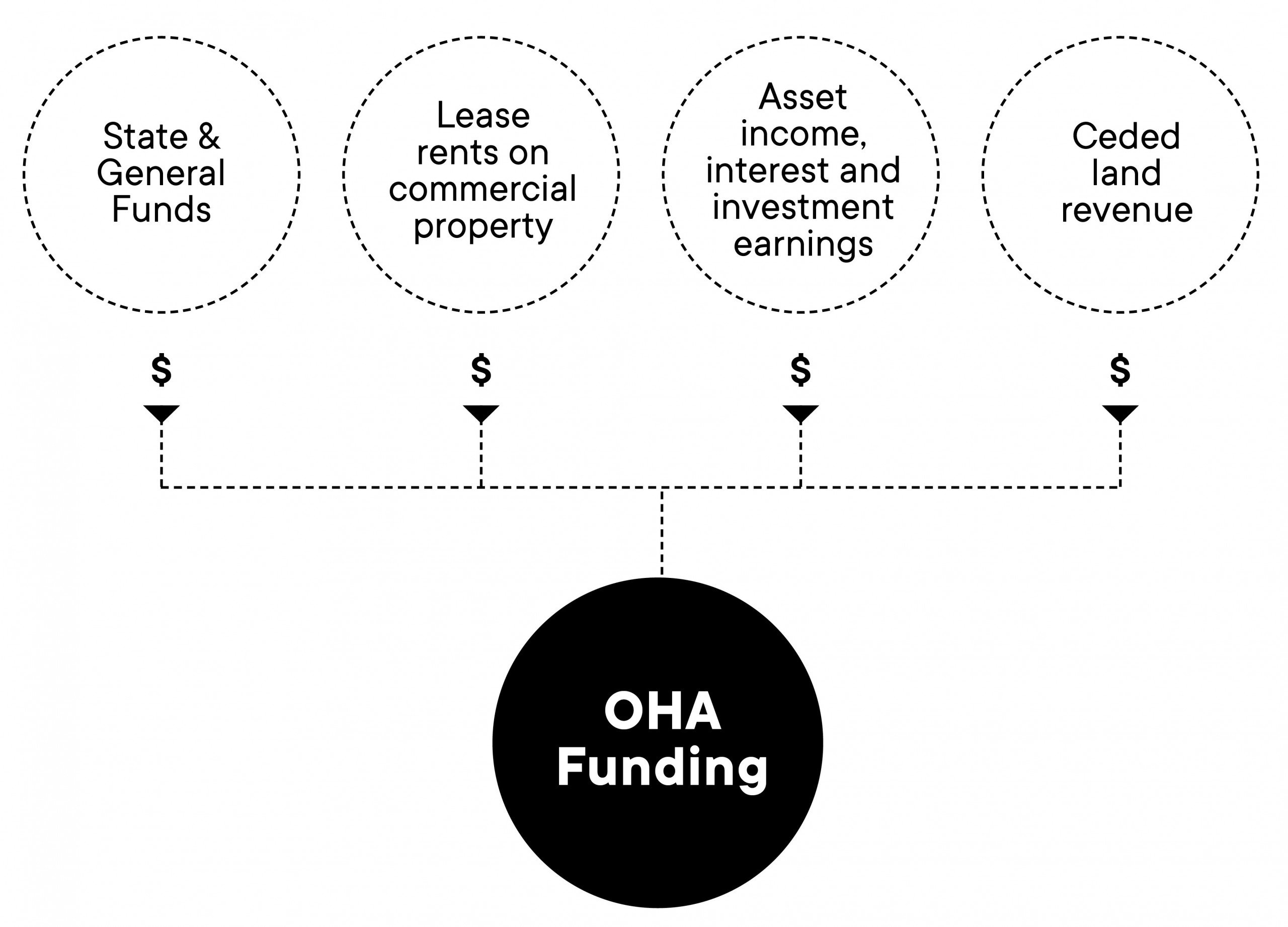

OHA gets its funding from several sources, including state general funds, lease rents on commercial property it owns, asset income and interest and investment earnings, and ceded land revenue.

A big chunk comes from this last category. As mandated in the Hawaii Admission Act, the federal law that turned Hawaii from a U.S. territory to a state, the income from approximately 1.8 million acres of ceded lands must be used for five purposes, one of which is bettering the conditions of Native Hawaiians.

In 1980, the state Legislature determined that 20 percent of ceded land revenues would go to OHA to fulfill its mission of bettering the conditions of Native Hawaiians. But in the nearly four decades since, the state and OHA have disagreed about which ceded lands OHA should receive revenues from.

OHA sued in federal court in 1985. In 1993, the state paid $136.5 million in back revenues.

In 2006, the Legislature agreed to pay OHA $15.1 million annually in public trust revenues. For the past several legislative sessions, OHA has introduced bills to adjust the 20 percent pro rata share of public trust revenues to $35 million annually.

“It’s overdue to re-examine it,” says state Sen. Maile Shimabukuro. “The big concern is whether or not the money is there. … A lot depends on the (state’s) financial outlook.”

As of press time, a House bill to increase OHA’s pro rata share to $35 million annually of the public land trust and give the organization $139 million in back pay was still alive.