Water Warning

Most people are smart enough to stay out of the ocean when signs warn about bacteria in the water. The problem is we don’t always get that warning, or get it quickly enough, because Hawaii has 303 miles of recreational shoreline and only six state inspectors testing for bacteria.

The good news is that volunteers on Kauai and Oahu are also testing the water, and a program proposed for testing in Hilo Bay could give people immediate warnings of polluted water. Best of all, Hawaii’s location in the middle of the Pacific helps keep our nearshore water clean.

Bacteria in the ocean can make people with no open wounds sick in many ways: skin, eye, ear and staph infections, as well as gastrointestinal illnesses that lead to nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and fever.

Wastewater that reaches beach waters is the biggest concern, says Watson Okubo, monitoring and analysis section supervisor for the state Department of Health’s Clean Water Branch. That’s what the branch’s six inspectors constantly test for: indicators of human fecal contamination, such as bacterial indicators, nutrients and geochemical parameters such as pH, temperature and turbidity (the cloudiness of the water).

When nearshore waters have elevated levels of bacteria, the branch investigates the cause, which is not always immediately clear. Okubo cites Kahana Bay.

Wataru Kumagai takes water

samples at Magic Island, in Ala Moana Beach Park. The beach park is probably the busiest in Hawaii, so its water gets tested at least once a week by the Hawaii Department of Health’s Clean Water Branch. Photo by Logan Mock-Bunting

“You would think that the high counts at the bay would be at the boat ramp and the restroom because of the cesspool, but, actually, the water’s coming out of Kahana Stream from higher elevations. And it was feeding the whole bay. So it’s very challenging to understand bacteria in recreational waters because it’s not very simple,” he says. “And that’s why you really need to understand the venue, the location, the contributing factors, and other testing that was done later on in Kahana, which showed the high bacteria counts were not from humans.”

MONITORING THE WATER

The Clean Water Branch uses two indicator bacteria to determine if a beach is contaminated with fecal matter: enterococci and clostridium perfringens. The two are found together, though a high level of one and a low level of the other doesn’t indicate human fecal contamination, Okubo says. It’s when both counts are high that a beach may be contaminated, and that’s when the branch would do an initial survey and resample the next day. The inspectors and Okubo often have to make a judgment call while awaiting test results: Put up warning signs immediately or wait for the lab results. Because the branch receives funding from the EPA’s Beach Act grant, it has to notify the public when recreational waters are not meeting or are not expected to meet applicable quality standards.

Sample sites that exceed water-quality standards half or more of the time could get permanent warning signs. At press time, Okubo said new caution signs created by the Clean Water Branch and Surfrider Foundation’s Oahu chapter were being reviewed by stakeholders.

The two kinds of bacteria aren’t foolproof clues of human waste. They can both be found in animals, and enterococci, the Environmental Protection Agency-approved indicator, can be found in soils, sediment and decaying matter. Ironically, bacteria from human waste is the most dangerous to humans.

Hawaii has 303 miles of recreational shoreline, according to the 2014 state Water Quality Monitoring and Assessment Report, and the Clean Water Branch focuses on monitoring the nearshore waters: between the shore and 300 meters out. The mouths of streams are also monitored.

Samples are collected in knee-deep water, with 500 milliliter containers submerged about elbow depth. Measurements for the physical characteristics of the water, such as temperature, salinity, pH and turbidity, are also taken.

Okubo says the major costs of sampling water are equipment and manpower. Testing for enterococci can be done with a kit; however, it’s much more complicated for clostridium. The water sample has to be filtered, placed in a petri dish with a gel that helps to isolate and identify clostridium in the water sample, and put in an anaerobic incubator, which will require a full lab to count the colonies of bacteria.

The state water-quality standards and adopted EPA standards say enterococci counts cannot exceed a geometric mean of 35 colony-forming units per 100 milliliters over any 30-day period, or a beach action value of 130 colony-forming units per 100 milliliters. For clostridium perfringens, the alert level is 50 colony-forming units per 100 milliliters.

The Clean Water Branch has 446 identified sites to test around the state, but has only six people to do the job. With no labs on Lanai and Molokai to immediately test samples, that leaves one person to test 104 sites on Hawaii Island, one to test 81 sites on Maui and one to test 73 sites on Kauai. The remaining three people test 145 sites on Oahu. EPA funding – $300,000 to $330,000 a year – can’t cover all six positions, Okubo says, so most are funded by the state.

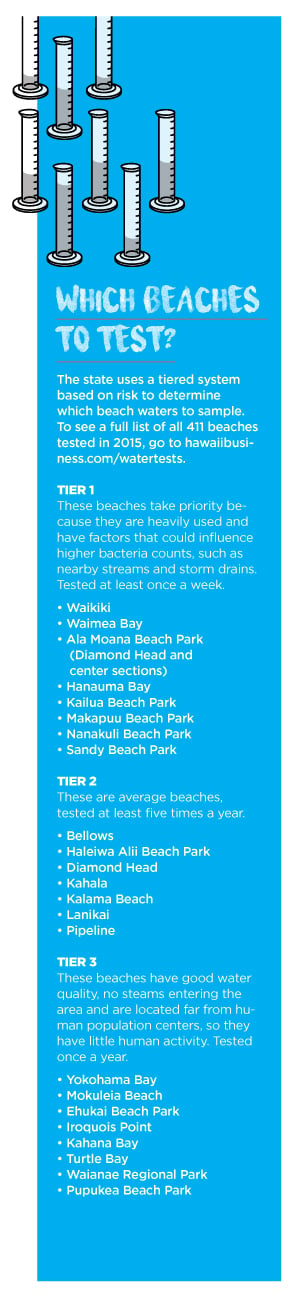

With so many sites to test, the Clean Water Branch categorizes beaches based on how likely they are to be contaminated by human fecal matter. Some beaches are tested once a week; others once a year.

High human use, a breakwater, a nearby stream and a nearby storm drain make for a tier-one, high-risk beach. “The more humans go, the higher the bacteria’s going to be in the water,” Okubo says. “There may be unknown sewage spills and the monitoring will pick that up.”

Picture Ala Moana Beach Park during a three-day weekend. Thousands of people will be there, making for an adverse situation, Okubo says. “I know a lot of people don’t look at it that way, but, from the health perspective, the more people recreating in one location, the health risk goes up because we’re looking at human fecal contamination. … If you don’t want to be at risk, then you go someplace not too many people go.”

In addition, degree of dilution plays a role. Generally speaking, if there’s no water movement and a lot of people are in the water, there’s a bigger risk of exposure to sewage from bathers, especially if there are no bathrooms nearby, according to a 1999 World Health Organization report on health-based monitoring of recreational waters.

A JUMP IN BACTERIA LEVELS

In 2014, the state found high bacteria levels in Kahaluu Lagoon and the channel leading into Kaneohe Bay. There are an estimated 600 cesspools in the area, so leakage and runoff were suspected as the causes. The state is partnering with UH scientists to study the interaction between the groundwater and surface water to help identify where the contamination is coming from and where it’s going.

An earlier study looked at the connection between cesspools and nearshore pollution. Working with the Coral Reef Alliance, UH Hilo marine science researchers Tracy Wiegner and Steven Colbert studied Puako on Hawaii Island, a community of about 160 homes that heavily relies on cesspools and septic tanks to dispose of sewage. Dye tracer studies found that sewage from cesspools could reach the seeps along the coast in as little as nine hours, or up to three or four days, meaning there’s little time for any pathogens to be lost or nutrients to be removed from the wastewater.

“The shorter the travel time, the more similar it is to swimming in raw sewage,” Colbert says. The travel time depends on how far the cesspool is from the shore and how big the cracks in the rocks are that allow water to flow, he adds. The cesspools in Puako were about 100 feet from the shore.

Wiegner says sewage in Puako ocean waters seem to be concentrated within 100 to 200 feet of the shore; however, there also seems to be evidence that wastewater will also discharge through seeps on the seafloor – which is where the team will now be concentrating further efforts to figure out how much sewage is coming up.

Currently, the Coral Reef Alliance and the Puako Community Association are looking at getting a private onsite treatment plant built, the best option according to a feasibility study.

The problem with cesspools is they do not treat wastewater; they’re unlined holding areas underground that allow untreated wastewater to percolate into the surrounding soil. Until March, Hawaii was the only state that still allowed new construction of small cesspools, meaning cesspools that serve less than 20 people. New small cesspools are now banned. Large-capacity cesspools were banned in 2000 (existing ones had to be upgraded or closed by April 2005). However, there are still 88,000 cesspools in the state, with almost half located on Hawaii Island. Of those, 6,900 are within 750 feet of a shoreline and have a greater potential to introduce harmful pollutants to the ocean than those farther inland, according to Hawaii’s Nonpoint Source Management Plan for 2015-2020.

“Our populations are growing, so stopping that input of raw sewage to our shorelines is a very important step, but there’s more that can be done,” Colbert says.

While connecting residences using cesspools and other on-site disposal systems to wastewater treatment systems seems like a simple solution, Okubo says, there’s not enough room to put a sewer line in every community. Sina Pruder, chief of the state’s Wastewater Branch, says cost is also a challenge. It would take millions of dollars to install sewer infrastructures in the state’s many rural areas, and sewer fees collected in these areas would not be enough to pay for construction and maintenance.

At the beginning of 2016, the Wastewater Branch started its tax-credit program for replacing cesspools located within 200 feet of a shoreline, perennial stream or wetland, or when the sewage takes less than two years to reach a public source of drinking water. However, Pruder says few people have used the credit of up to $10,000 for each qualified cesspool. This money covers a portion of the cost to upgrade to a septic tank or aerobic treatment unit. Pruder says the price will vary based on site conditions, but she estimates a septic tank would cost $8,000 to $20,000 and an aerobic treatment unit $20,000 to $30,000.

When upgrading to a new wastewater disposal system, a home’s location is a factor in determining which system to pick. Those near the shore or a stream usually have high groundwater, Pruder says, so, if a homeowner were to put in a leach or drainage field, the Department of Health requires there be three feet separating the bottom of the field and the groundwater. The soil usually provides a natural treatment for the wastewater, so, if homeowners don’t have that separation, they have to install an aerobic treatment unit that disinfects the wastewater, she says.

LEAKS AND SPILLS

Bacteria can also get into nearshore waters through leaks and spills from the sewer system. In 2015, the Clean Water Branch reported 19 sewage spills around the state, with 11 affecting coastal waters, but the spills didn’t always reach the nearby beaches. Okubo says this is because spills dilute before reaching beaches.

Marvin Heskett, water-quality expert with Surfrider Foundation’s Oahu chapter and senior chemist at Element Environmental LLC, says nonpoint source pollution is a big concern. Nonpoint source means the pollution originates from more than one location. During a storm, rainwater picks up pollutants as it makes its way down to the ocean.

He cites the area around Waikiki’s Kapahulu groin as an example: “That’s usually especially bad after long dry periods, and then you get your first initial storm and it’s kind of flushing streets and neighborhoods clean, and all that material comes rushing down out of storm-drain pipes.”

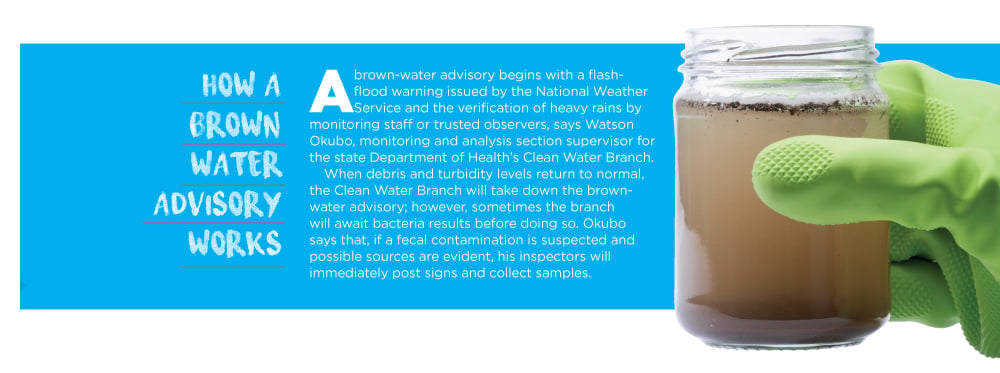

The Clean Water Branch also watches streams; however, no matter which stream is tested, enterococci counts are going to be high, Okubo says, because of sediment and soil. In addition, counts jump each time it rains, so Okubo began issuing brown-water advisories after he became supervisor of the branch’s monitoring section in December 2003.

“I developed the brown-water advisory because of overflowing cesspools, unknown chemicals, pesticides, herbicides, dead animals being washed into the ocean,” he says. “So, if the water’s brown, stay out. Because you get all these leptospirosis issues coming up. People think, ‘Oh, if you’re in the salt water you don’t have to worry about the leptospirosis.’ It’s not true, because it survives long enough in the coastal water where all the salinity is depressed.”

In the 24 hours it takes to get bacteria test results back, beaches may or may not have warning signs based on the judgment of Okubo and his team. That’s why Wiegner and Colbert are seeking funding for a pilot project that could inform people whether the beach water is safe in real time. Their model would be based on salinity and turbidity, which appear to be related to bacterial counts, and would be recorded by a buoy in Hilo Bay.

“If we have that established relationship between those two parameters, we could make calls for bacteria counts, at least predicted bacteria counts based on turbidity and salinity being measured in the water, based on the buoy,” Wiegner says.

ALOHA FOR OUR WATER

Although there may be reports of high bacteria and brown water every once in a while, the quality of Hawaii’s beach water is clean enough that the Surfrider Foundation’s Heskett will go in as much as possible. In fact, Surfrider’s Oahu and Kauai chapters are testing their islands’ waters, focusing on areas that they feel don’t get enough attention.

On Kauai, that means surf sites and streams. That’s because Kauai has more waterfalls and rainfall than other islands, meaning bacteria, such as those from cesspools and animal waste, will travel down the streams and into the ocean, Surfrider Kauai chairman Carl Berg says. His chapter has been monitoring water quality for 10 years and has found that some streams are chronically polluted, such as Waiopili Stream and Nawiliwili Stream, which constantly have enterococci counts exceeding state standards.

1) UH Hilo summer interns and graduate students collect water quality and algae samples at Puako for a project documenting nearshore sewage pollution. The students are Devon Aguiar, Jazmine Panelo, Leilani Abaya, Bryan Tonga, and Belytza Velez-Gamez.

2) Leilani Abaya, a master’s student at UH Hilo’s graduate program in Tropical Conservation Biology and Environmental Science, filters water samples from Puako to determine concentrations of fecal indicator bacteria. These bacteria are used to assess whether the water is polluted with sewage.

3) Evelyn Braun, a UH Hilo summer intern with the Pacific Internship Programs for Exploring Science, measures water turbidity (cloudiness) at Waialea Beach, one of the stations for the Puako sewage project. Photos by Tracy Wiegner

Both the Kauai and Oahu chapters of the Surfrider Foundation only test for enterococci. According to Heskett, the secondary tracer, clostridium perfringens, is not tested because it requires an anaerobic chamber, which is outside the scope of Surfrider’s equipment and volunteer effort.

However, the main takeaway is that, because the island is in the middle of the Pacific, Kauai’s surf sites are generally clean. Berg says, “But, when you start getting water coming off the land, that’s when it brings with it all sorts of garbage and bacteria and viruses that can make people sick, and that’s why, at the bottom of our list in red, we have places like Hanamaulu Stream, Nawiliwili Stream, Waiopili Stream.”

In addition to testing for enterococci, the Oahu Surfrider chapter is also concerned with other pollutants. It has a separate water quality monitoring program that will track four sites around the island for enterococci and clostridium and over 100 pollutants, says Matt Moore, chapter treasurer and water-quality specialist.

The program is funded by a $300,000 grant. The money arises out of a settlement after millions of gallons of storm water leaked from the Waimanalo Gulch Sanitary Landfill into nearshore waters in 2011, Moore says. The program started over the summer and is expected to last two to three years. The test sites will include Nanakuli, Fort DeRussy, Sunset Beach and Castles in Kailua, and the frequency of testing will be based on brown-water events: the group wants to know the levels before, during and after storms.

“We’re just trying to inform the public of what’s in the water and bring to light some of the issues that have been around for a while without a lot of people knowing,” Moore says.

Nevertheless, Hawaii’s water quality is a lot better than places on the mainland, Okubo says, citing our location in the middle of the ocean, where currents and winds eventually clear everything away. But, we have to keep addressing the issues that arise.

“I was born in Hawaii, the water was good to me and my family,” he says. “My grandfather was a fisherman, my father was a diver fisherman, I supplemented my income by fishing in my younger days, made good money. And so I have an aloha for the ocean. I don’t want to screw it up. I want to do as much as I can. All these big issues that are coming up, hopefully I can put down the template for how we are going to do it, do the framework, so I can retire.”

LEARN THREE THINGS YOU CAN DO TO HELP PROTECT HAWAII’S WATER, AS TOLD BY AUSTIN KINO