Wasted

We may buy that clamshell of beautiful, ripe strawberries with the best of intentions – pancakes! cobbler! fruit salad! – but when the end of the week comes and they’re getting soft and fuzzy in the back of the produce drawer, we’re likely to throw them in the trash. Multiply that process by several thousand households, and you’ll get a mountain of moldy berries.

How big is that mountain? That’s the question UH economists Matthew Loke and PingSun Leung set out to answer, with a study aimed at quantifying Hawaii’s food waste. Their findings, published in 2015 in the journal Waste Management & Research, estimate that, even as Hawaii residents pay some of the highest food prices in the country, we still throw out around 237,000 tons of food per year, or more than 26 percent of the available food supply.

How big is that mountain? That’s the question UH economists Matthew Loke and PingSun Leung set out to answer, with a study aimed at quantifying Hawaii’s food waste. Their findings, published in 2015 in the journal Waste Management & Research, estimate that, even as Hawaii residents pay some of the highest food prices in the country, we still throw out around 237,000 tons of food per year, or more than 26 percent of the available food supply.

For an island state with limited landfill space, that’s a lot of wilted spinach and spoiled chicken to toss. Maybe more concerning, it’s a missed opportunity for a state that imports around 88 percent of its food and in which nearly 1 in 5 residents relies on a food bank for assistance, says Loke, a food and agricultural economist at the UH Manoa’s College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, and lead author on the study. “If we reduce our food waste, then, naturally, food security should increase,” he says.

Loke became interested in the issue after listening to a report about food waste on National Public Radio. He wondered how Hawaii stacked up. First, Hawaii’s food economy is unlike that of the Mainland. Most of our food is imported, which means most waste starts at the harbor, not at the farm. The visitor industry brings in millions of tourists, who tend to splurge on food and waste a lot. And we have a large military population that has special access to cheap food at commissaries. How do those factors affect the way we eat – and waste, he wondered.

“From the demand side, and the supply side,” Loke says, “Hawaii is kind of unique.”

The Price of Waste

Overall, the Aloha State is less wasteful than the rest of the country, discarding around 356 pounds of food per person,

per year, versus 429 pounds per capita on the mainland.

That makes sense to Loke. “If you look at the dollar value of the waste, it’s one-third more expensive compared to the U.S. mainland,” he says. “As the price of food is more expensive, you tend to be more conservative and

waste less.”

Still, Hawaii’s waste doesn’t come cheap. Loke’s study estimates the total value of the state’s food waste in a single year is more than $1 billion – about 1.5 percent of Hawaii’s total GDP. That comes to almost $700 in wasted food per person, per year.

It’s a lot more than people waste in other parts of the world, especially developing countries. People in sub-Saharan Africa and south and southeast Asia throw out less than 24 pounds of food per person each year, according to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization. “High-income countries tend to waste more, and low-income countries tend to waste a lot less,” Loke notes.

In Hawaii, he found that most food waste occurred at the consumer level, followed by the distribution and retail stages. The least waste occurred at the post-harvest and packing stages, suggesting that efforts to reduce waste would be most effective if they target consumers, he says.

Researchers compiled data from the USDA, Hawaii Department of Health solid waste reports, surveys and other sources to come up with estimates for how much food is wasted in Hawaii.

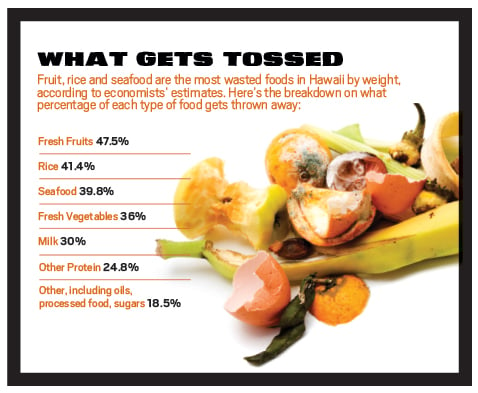

Fresh fruits were the most wasted commodity by weight, with almost half of all fruit, 47.5 percent, being discarded before it reaches our stomachs. A lot of rice and seafood is also thrown away, with 41.4 percent and 39.8 percent being wasted, respectively.

The problem with throwing away food goes beyond wasting money and clogging landfills, notes Amanda Hong, food recovery specialist for the Environmental Protection Agency’s Pacific-Southwest region. The EPA estimates that, nationwide, food comprises around 20 percent of the waste stream, she notes. For landfills, it’s not just an issue of using space. Buried food rots under anaerobic conditions, producing methane, a greenhouse gas that’s at least 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Food waste also wastes other resources. The Natural Resources Defense Council has found that 25 percent of the water used in the U.S. goes to produce food that eventually gets thrown away, Hong says. That’s a heavy toll for food producers like California, which is suffering under a long drought. “Food, especially, is incredibly energy-resource intensive,” Hong says. “It takes a lot of resources to transport, package and store food, and to throw it away is really wasteful.”

Rescued Food

Saving food from the garbage is something Daniel Delbrel thinks about every day. To the culinary director for the Sheraton Waikiki, food wasted is money lost – not just because it was bought and never eaten, but also because the hotel must pay to have it hauled away. From investing in blast chillers to quickly bring hot food down to a safe temperature for storage, to buying a filtration system for the hotel’s six deep fryers to cut the amount of cooking oil they use in half, Delbrel is always looking for ways to waste less food.

For most plated dishes, he says, very little is thrown away. But buffets are a different story. “If nobody was eating buffet, it would be a simpler world,” Delbrel says.

Wholesalers such as Armstrong Produce use refrigerated trucks and warehouses to maintain a tight “cold chain” that keeps produce fresh for longer. But if bad weather or pests damage a crop

in the field, and it arrives in less than perfect condition, consumers may refuse to buy it, which increases the chances that it will get thrown out. Photo: David Croxford

Once food has been put out on the buffet line, health regulations forbid the hotel from serving it again. Customer choice plays a big role in what gets wasted. For each buffet, the hotel must offer an assortment of options, never knowing what customers will prefer. “Today it’s going to be the beef, tomorrow it’s going to be the chicken, or seafood, or so forth,” Delbrel says. With a big buffet, “If you feed 1,000 people, you could literally feed another 100 people with what’s left.”

He does what he can to minimize waste. “Let’s say we have a cold buffet, and we were expecting to do 500 people and only 300 show up,” he says. “The food that was prepped in the kitchen but not served, that food is not wasted.” These leftovers will usually find their way to the employee cafeteria, which serves 700 to 800 hotel workers a day. “If we know we have a buffet, we actually cut down on the quantities we order for the cafeteria,” Delbrel says.

Loke says his research revealed the visitor industry is a double-edged sword on food waste. On one hand, tourists in the mood to splurge tend to order – and waste – more food than residents. At the same time, visitor demand for fresh and high-quality products increases the frequency of food shipments to Hawaii.

“This higher quality and higher frequency is actually a good thing, because that can lower the cost of food,” he says. “More frequent shipments helps to lower inventories, and lower inventories lead to cost savings as well as less food waste.”

Delbrel acknowledges his hotel will never eliminate waste completely. “The more we waste, the more it costs us, so we like to keep it as close as possible,” he says. “But not to the point where we have the customer complaining. We don’t want the customer to say at the end of a function, ‘You ran out of food. How come?’ ”

The Sheraton donates food that can’t be served again but is still edible to organizations like Aloha Harvest. The Honolulu nonprofit “rescues” unused food from restaurants, caterers, wholesalers and retailers, then distributes it to around 180 social service agencies that feed the hungry and homeless.

“We never know what we’re going to get,” says Kuulei Williams, executive director of Aloha Harvest. “It could be chicken, it could be pastries, bread. It could be a caterer who did an event and has excess food. It could be a grocery store that has deli products.”

Donating excess food to the hungry is one step recommended by the EPA to reduce waste, Hong notes. Food that’s not fit for human consumption should first be used for animal feed, then for energy generation, then compost. “Only if we can’t do any of the above should we be landfilling or incinerating food waste,” Hong says.

Even though it may result in fewer leftovers for her organization, Williams says, seeing restaurants improve their efficiency and reduce their waste is encouraging. After the economic downturn in 2008, she noticed more restaurants moving to cook-to-order menus, which resulted in less unused food than prepared dishes like soup

and lasagna. Many restaurants have stuck with the new ordering system, she notes.

“They would call and say, ‘I’m sorry, we don’t have as much to donate because we’ve gone to this type of menu’ – which, of course, is fine with us,” she says. “It forced a lot of the restaurants to really evaluate how they’re ordering their food.”

The Fish-Head Factor

There are a host of reasons to feel bad about throwing food away, but do we really want to join the clean-plate club? Loke is not a hardliner. Bread crumbs and meat trimmings are just some of the items we’d probably rather not have to choke down. “In certain ethnic groups, fish heads are prized,” he says. “In others, they aren’t eaten at all. So there’s a preference issue when it comes to food.”

Aloha Harvest is a nonprofit that “rescues” unused food from restaurants, caterers, wholesalers and retailers, then distributes it to around 180 social service agencies that feed the hungry and homeless. Photo: David Croxford

At the retail level, shopping preferences come into play. “If you want to reduce waste in a retail store, then you put out fewer products. You only put out a few products and when it’s all sold out you put out a new batch. But if you do that, it’s inconvenient to the customer, and they might not come back. So a lot of retail stores tend to overstock to keep customers happy,” Loke says.

It’s also important to look at the opportunity cost of saving food, Loke says. Buying our ingredients fresh every day and cooking from scratch would waste less food, but would also add hours of additional labor. “We have to spend more time and more resources in order to reduce food waste, and oftentimes it’s just not worth it,” he says.

Tish Uehara, director of marketing for Armstrong Produce, suspects that most waste occurs with consumers or retailers, since wholesalers like her company use refrigerated trucks and warehouses to maintain a tight “cold chain” when bringing produce to market, to ensure food stays at a safe temperature.

While most food is imported to the Islands, problems on the farms can lead to waste down the line, she notes. If bad weather or pests affect a crop in California, it may arrive in poorer quality than usual.

That’s where consumer preferences can again drive food to be dumped,

she notes.

“People, no matter what, they expect perfection,” Uehara says. “Oftentimes, they have no real concept about what it takes to produce those items, what it takes to maintain that cold chain, what it takes to get those products to our location in the middle of the ocean.”

Plus, fresh fruits and vegetables are among the first to spoil. “If you really want to reduce food waste, we could be consuming a lot of processed and canned foods,” Loke says, “but that’s not as healthy as fresh.”

That’s an issue he sees playing out in his own family’s kitchen. What gets wasted the most?

“I guess it would be the salad greens,” he says. “We’re so busy and we forget to eat it, and all of a sudden you look at it and it doesn’t look so good anymore.”

Photo: Thinkstock

Success Story: Pearl City High

Composting uneaten food started as a job-training program for Pearl City High School special education students, but the program was such a success, it won the school a national award from the Environmental Protection Agency.

“They achieved a 97.5 percent food waste diversion rate overall, which is very, very impressive,” says Amanda Hong, food recovery specialist for the EPA’s Pacific-Southwest Region. “They let very little food waste go to the landfill.”

Pearl City won the EPA’s 2015 Food Recovery Challenge award for K-12 schools. The school partnered with Waikiki Worm Co., a vermiculture, or worm-composting business.

Special education teacher Joanne Kimura says students set up collection tables near cafeteria garbage cans at lunch, separating items. Meats were fed to black soldier flies, which a researcher was studying as a potential chicken feed. Other items were used for vermiculture or hot composting, producing worm casings

and mulch, which were sold to gardeners

on weekends.

“The kids waste a lot of food,” Kimura says. “We did reduce a significant amount, and all of (the diverted waste) was actually producing things that people wanted.”

One student went on to get a job in vermiculture. The program was scaled back this year because of time constraints. Kimura notes the project was labor intensive. “Collecting means the kids have to give up their lunch, and it pretty much takes the whole period after lunch to do everything,” she says.

While some students embraced the project, others were more reluctant.

“It’s not for everybody,” Kimura says. “Some people won’t even touch the worms. I don’t know why – they don’t bite or anything.”