Waikiki Construction Refreshes Hotels

In some ways, construction and Waikiki go hand-in-hand. After all, the pleasure palaces along the beach have provided many of the largest recent private construction projects in the state. By some counts, more than $2 billion has been spent over the last 10 years renovating and redeveloping Waikiki’s crown jewels. And that’s not counting the myriad smaller projects. But the question that both hotel owners and construction companies are asking is: What will get built or renovated in the next few years and in Waikiki’s long-term future?

In some ways, construction and Waikiki go hand-in-hand. After all, the pleasure palaces along the beach have provided many of the largest recent private construction projects in the state. By some counts, more than $2 billion has been spent over the last 10 years renovating and redeveloping Waikiki’s crown jewels. And that’s not counting the myriad smaller projects. But the question that both hotel owners and construction companies are asking is: What will get built or renovated in the next few years and in Waikiki’s long-term future?

Snapshot in time

There are currently more than 500 active building permits in Waikiki. The vast majority are manini – minor electrical and plumbing upgrades, new grease traps, window relocations and flooring jobs – but there are also several big projects:

• For months, road crews and construction gangs have been resurfacing Waikiki’s streets and sidewalks, spending millions of dollars in anticipation of APEC.

• On Olohana Street, Wyndham is finishing up the redevelopment of the Royal Gardens, its new timeshare property.

• The Mau family is nearly done with the extension of the Waikiki Shopping Plaza on Kalakaua, already snagging major tenants like Victoria’s Secret and A/X.

• Almost unnoticed, a Mainland developer called the Chartres Group is completely renovating the old Ocean Resort Hotel. They hope to have one tower done in time for APEC, then gut the other tower and convert it all to a Hyatt Place.

That’s today. But to truly understand construction in Waikiki, it helps to have more perspective. You have to look into the recent past to get a sense of the scale of the projects that can be done and gaze a little into the future to see the opportunities – and obstacles – ahead. You also have to poke around in global credit markets to understand why anyone would invest in Waikiki construction.

Perhaps the best example of investment is Kyo-ya’s ongoing renovation and redevelopment of its beachfront and Kalakaua-facing hotels. According to executive VP Greg Dickhens, Kyo-ya’s plan has two phases. Phase I involved not only renovations, but a diversification of the company’s assets outside the Sheraton nameplate. “We started with the Moana Surfrider back in 2007,” Dickhens says. “We spent about $40 million renovating the historic building, converting that from a Sheraton to a Westin. We put in a new restaurant, (called) The Beachhouse, and a 16,000-square-foot spa, really upgrading the product.”

At almost the same time, the company began a major renovation of the Sheraton Waikiki, its largest hotel and biggest moneymaker. According to Dickhens, “That was about a 5-year renovation project that included all the hotel guest rooms, all the corridors and brand new pools. We renovated the meeting space, redid the lobby and replaced every elevator in the building. That was about a $150 million renovation that we completed in 2010.”

At almost the same time, the company began a major renovation of the Sheraton Waikiki, its largest hotel and biggest moneymaker. According to Dickhens, “That was about a 5-year renovation project that included all the hotel guest rooms, all the corridors and brand new pools. We renovated the meeting space, redid the lobby and replaced every elevator in the building. That was about a $150 million renovation that we completed in 2010.”

Although its largest hotel remained in the Sheraton fold, Kyo-ya decided to go more up-market with the classic Royal Hawaiian: “We closed that property for about seven months in 2008,” Dickhens says, “and spent about $70 million renovating that hotel and upgrading it to our Luxury Collection level. Then, we actually just went back and renovated the Tower Building this year. We spent another $10 million on just the tower, so that was a significant refresh. In fact, we spent about $60,000 a room. We ripped out all the bathrooms and put in all new furniture, so it was a complete gut of the guest rooms. In total, the repositioning was about an $80 million renovation. Between the three properties – the Sheraton Waikiki, the Moana Surfrider and the Royal Hawaiian – it’s about $270 million to $280 million.”

One view of the future

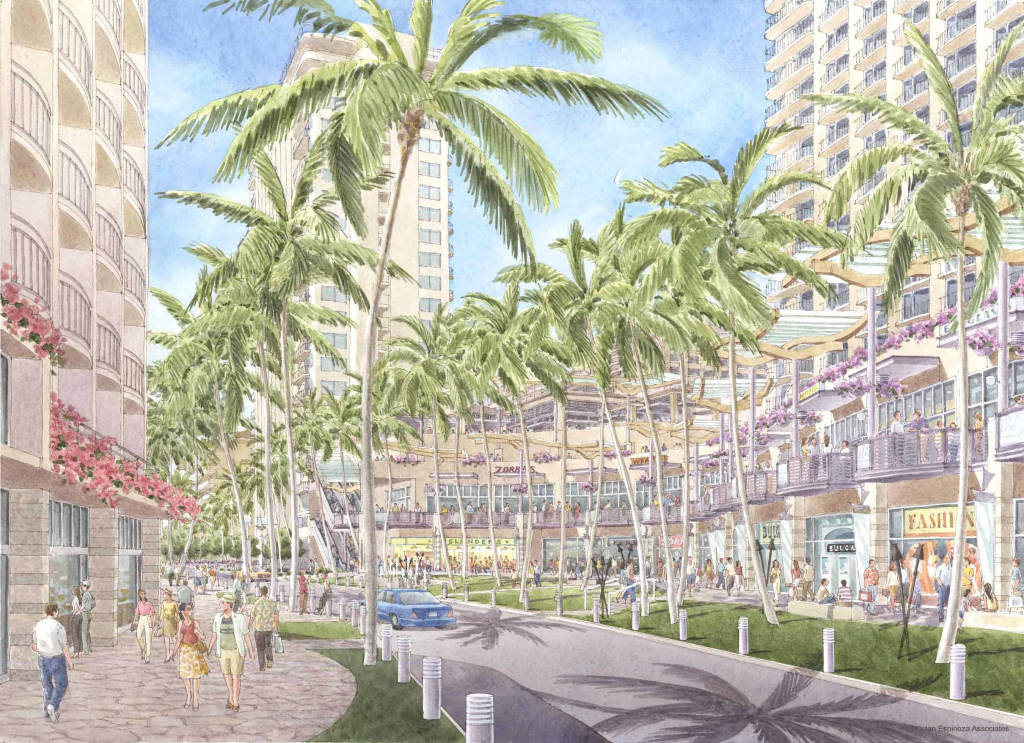

These numbers are enormous for private sector construction in Hawaii, but they may be dwarfed by Phase II of Kyo-ya’s ambitious strategy. This phase calls for a $550 million redevelopment of the 1,035-room Princess Kaiulani Hotel and a controversial plan to raze the old Diamond Head Tower of the Moana Surfrider and replace it with a new, 26-story, $140 million tower. The result wouldn’t simply be a matter of construction; it would reflect a major change in the company’s business model. The redevelopment of the Princess Kaiulani, for example, will underscore the visitor industry’s evolution from pure hotel operations to mixed-use. “Over the past three years,” Dickhens says, “we’ve been going through the entitlement process to redevelop that asset to include a mix of hotel, residential, timeshare and retail components. As approved, the hotel will include 650 rooms, 150 two-bedroom timeshare units, and 120 whole-ownership residential units. In addition, there will be 82,000 square feet of retail.” The project involves a massive renovation of Ainahau Tower, while tearing down the rest of the property to build a new 34-story tower, a parking structure, and new retail and meeting facilities. In other words, it’s going to be a construction bonanza.

These numbers are enormous for private sector construction in Hawaii, but they may be dwarfed by Phase II of Kyo-ya’s ambitious strategy. This phase calls for a $550 million redevelopment of the 1,035-room Princess Kaiulani Hotel and a controversial plan to raze the old Diamond Head Tower of the Moana Surfrider and replace it with a new, 26-story, $140 million tower. The result wouldn’t simply be a matter of construction; it would reflect a major change in the company’s business model. The redevelopment of the Princess Kaiulani, for example, will underscore the visitor industry’s evolution from pure hotel operations to mixed-use. “Over the past three years,” Dickhens says, “we’ve been going through the entitlement process to redevelop that asset to include a mix of hotel, residential, timeshare and retail components. As approved, the hotel will include 650 rooms, 150 two-bedroom timeshare units, and 120 whole-ownership residential units. In addition, there will be 82,000 square feet of retail.” The project involves a massive renovation of Ainahau Tower, while tearing down the rest of the property to build a new 34-story tower, a parking structure, and new retail and meeting facilities. In other words, it’s going to be a construction bonanza.

Although there doesn’t seem to be much resistance to the Princess Kaiulani project, Kyo-ya’s plans for the Diamond Head Tower across Kalakaua are more contentious. That’s because the deal requires a variance from setback laws and height restrictions for new construction on the beach. That’s drawn protests from environmentalists and others who say the new tower would loom over the beach, block views and change the character of the neighborhood. That would violate the spirit of the Waikiki Special District Guidelines, which were intended, in part, to prevent Waikiki Beach from being walled off from the rest of Waikiki by a row of towers. But for Kyo-ya, the logic of the new tower is inexorable: the old Diamond Head Tower, which was built in the 1950s, is simply uneconomical. It can’t generate enough revenue to justify a major renovation. And to make a new property pay, it not only has to exceed the setback requirements, it has to embrace the modern paradigm of mixed use. That means part of the tower has to be timeshare or condominium.

Kyo-ya had planned to begin construction on its new Diamond Head Tower this year, but for now the project is lost in the appeals process. Even though the company already got unanimous approval of its setback variance from the zoning board, there’s no guarantee the project won’t be held up indefinitely by the usual entitlement slow dance. As David Carey III, CEO of Outrigger Enterprises, points out, permitting and entitlement snafus are just the beginning of the challenges to construction in Waikiki. The real problem, he says, is paying for it. “Everybody thinks about the approval part, but part of the process of construction and developing is you have to have the source of funds in order to proceed with the project.” Carey offers the Beach Walk project as an illustration.

Hidden costs

In many ways, Outrigger’s nearly $1 billion Waikiki Beach Walk project is the paragon of development. It’s been both a commercial and aesthetic success, converting a shabby neighborhood into vibrant and profitable mixed-use. But Carey notes that a lot of that success was lucky timing. “The good thing for us, when we were doing the Waikiki Beach Walk, is that the sun was out in the capital markets and it was shining on us. We were easily able to raise both equity capital and debt capital and get the project done. If we had started the project last year, though, we might not have been able to raise the capital at an affordable level that would enable the project to go through.”

Carey says development in Waikiki is run through with these kinds of contingencies. “There are several things that feed into the construction of new projects,” he says. “First, you have to have demand in the marketplace that says there’s a need for the product. Then, the cost of the project has to be at a place where you believe you can sell it at that demand level. Finally, you have to have a cost of capital that enables you to build it at a price to serve the demand level. That’s a lot of things to line up at once.”

“The challenge in Hawaii,” he says, “and in Waikiki in particular, is that the entitlement process is very long; so, when you start, the demand may be there for the project that you conceived of, but by the time you finish the entitlement process, it may no longer be there. Or, it may be there, but the cost of capital may be too high to meet your pro forma. That’s what makes Hawaii really tough. It’s a good news/bad news kind of thing. The good news is if you get all those things done, it’s enormously successful. But the risk factors are very high.”

Carey also notes that development in Waikiki – particularly away from the beach – is hampered by cost constraints. “If you want to build a high-rise hotel,” he says, “the rule of thumb is you need to get a dollar of average-daily-rate for every $1,000 of construction costs. In Waikiki, it probably cost, at a minimum, $350,000 to $500,000 a key to build a high-rise hotel, which, using traditional underwriting, suggests you need $350 to $500 a night in average rate to make a pure hotel. There are very few locations that enable that kind of underwriting.” It’s this calculation, he says, that explains the paucity of new hotel projects.

If not hotels, what construction opportunities are left in Waikiki? There’s retail, of course. Successes like Beach Walk and the Royal Hawaiian Center have undoubtedly inspired projects from the Waikiki Shopping Plaza expansion to the proposed redevelopment of the International Marketplace. In fact, retail is an inevitable part of the trend toward mixed use, but, as Carey points out, the realities of financing make timeshare and whole ownership condominiums especially attractive.

“This is my own opinion,” Carey says. “Investors in timeshare and whole ownership condominiums do not have the same investment return criteria that a professional equity fund would have. So, the Blackstones of the world that bought Hilton, Cerberus that has Kyo-ya, Whitehouse Goldman that has pieces of hotels down the street, Deutsche Bank, etc., they all have fairly stringent return criteria. They talk of an unleveraged return in the teens and a leveraged return of as much as the twenties. That’s a pretty high bar.

“In contrast,” Carey says, “the average condominium owner doesn’t walk into their condominium purchase and say, ‘I need an internal rate of return of 25 percent.’ He thinks, ‘Hey, if I can cover my cash flow and real estate taxes and have a nice vacation home, wouldn’t that be great!’ If you calculate the equity return on that, it’s 1 percent, maybe 2 percent. And the timeshare purchaser doesn’t even think about return; they think about prepaying for their vacation. So, the cost of capital is lower for the developer of those kinds of projects. Trump Tower, for example, was a whole ownership condominium purchase. If the construction cost was $400 to $500 per square foot, it was sold at an average price of $1,600 per square foot. You can do the math.”

In fact, Outrigger took advantage of some of Trump’s windfall. “We actually owned that site,” Carey says. “We were originally planning that to be a high-rise hotel, so we went through exactly this same conversation.” Ultimately, Outrigger decided the numbers didn’t work for a hotel and sold the site as part of the Beach Walk project. In effect, they used the Trump project to help subsidize the rest of their mixed-use project, a strategy that takes a lot of risk out of development.

“That’s why Kyo-ya is so excited about a beachfront deal,” Carey says. “Their plan, I think, is to sell a bunch of the rooms in condominiums to create the equity capital that will allow them to cover the risk factor, then they can borrow the money to build the hotel part. But that only works on the beach, where you can get a high-ticket price. I don’t believe, in today’s world, you could get any of that kind of work done on Kuhio Avenue. I don’t think you could underwrite it – to use an industry word – to get financing for a high-rise hotel on Kuhio Avenue, because the average rate potential isn’t high enough to cover the cost of construction. Of course, that doesn’t mean you couldn’t underwrite the renovation of an existing hotel – we’ve made our career out of that.”

Carey points out another change that has affected the viability of development in Waikiki: the rising cost of leasehold land. He notes that leases are usually based on the price of the land. “And because of the acceleration in the price of land, lease costs have escalated dramatically,” he says. “That’s become a much, much, much bigger portion of the cost of running and operating or developing a hotel. Historically, the notion was, it was just like a loan. The landowner was getting 4, 5, 6 percent return, basically like a loan on a land purchase. But now the rate of return is closer to 6, 7, 8 percent, and the land price has skyrocketed.” Add that to the cost of capital and the unpredictability of the market and the prospects for new construction start to look pretty grim in Waikiki.

Rationale for more construction

It’s not like there aren’t any economic incentives to redevelop Waikiki. In fact, most observers in the travel industry say the changing demographics and expectations of today’s travelers mean that Waikiki infrastructure – in spite of all the recent renovations – is becoming obsolete. “If you look at the overall visitor product in Waikiki,” says Kyo-ya COO Ernie Nishizaki, “it’s predominately built in the 1960s and 1970s. The exceptions on either extreme are the Moana and the Royal Hawaiian, which were build in 1901 and 1927, and the Hyatt, the Halekulani and the Prince, which were built in the early 1980s. But really, we haven’t seen any new hotel product in 20 or 30 years.”

According to Nishizaki, the age of the hotel product has far-reaching implications on the marketability of Waikiki. “What you see in a typical hotel built in the 1970s is a 280-to-300-square-foot guest room, very small bathrooms, and limited amenities. But today’s visitor wants a guest room that’s 360 to 480 square feet, a larger guest room living area, as well as a much larger bathroom. That’s something that’s not provided today in Waikiki, with the exception of the Halekulani, so there’s a significant need to upgrade what we offer. If you want to attract that high-paying visitor from Japan, China, Korea and some of the emerging markets, you have to be able to compete with places like Bali and Cancun that have properties built in the last five years.” That’s one of the advantages of timeshare, Nishizaki says. Timeshare offers the kind of larger units with more amenities that today’s traveler demands.

Of course, you still need somewhere to put your development. And even as Kyo-ya explores the regulatory challenges of a teardown, others in the visitor industry seem to have more modest expectations for future construction in Waikiki. Some, like Rick Egged of the Waikiki Improvement Association, see pockets of opportunity for retail development scattered around Waikiki in places like the mauka end of Lewers and the vacant lot behind St. Anthony’s. Others are more cautious.

“Today,” says Outrigger’s David Carey, “my crystal ball says the most likely projects are going to be room renovations for hotels that have good enough bones that they can rationalize an upgrade.” He pauses a moment before adding, “And residential conversions of hotel properties; I actually think that’s going to happen.”

Hilton Hawaiian Village: Two Decades of Construction

2001

Kalia Tower construction

$95 million

Lagoon Tower renovation and conversion to timeshare

$36 million

2006

Construction of Ocean Crystal Chapel

$6 million

2007

Duke Kahanamoku Lagoon restoration

$15 million

2008

Ala Moana Boulevard road improvements

$9 million

Grand Waikikian construction

$350 million

2009

Paradise Pool construction (above)

$7 million

Tropics Bar and Grill construction

$11 million

2011

Rainbow Tower renovation

$45 million

2012

Alii Tower renovation

2013

Diamondhead Tower renovation

2014

Kalia Tower renovation

2015

Tapa Tower renovation

Hilton Master Plan

Two timeshare towers, retail and pool

Estimated cost: $760 million

Note: Timeline subject to change. Budget for most future projects not disclosed.