Wahine Getting It Done

Hands-on parenthood is a more than full-time job. So are most leadership positions. Combining the two, especially for women, is often seen as what The New York Times recently called a “head-on collision between motherhood and work.” But what if you want to be both a leader and a parent – and not a wreck?

We asked eight successful Hawaii leaders who are also mothers how they’re doing it (or, if their children are grown, how they did it). Nobody has it all figured out. But they all seem to be enjoying the ride.

Christine Camp’s Village: In front are Christine’s mother, Judy Camp, and son, Ethan; from left, her older sisters are Elizabeth Yamaguchi, June Freundschuh and Frances Muneno; at right is boyfriend Alan Schlissel.

Christine Camp was a business leader long before she became a mother. The real-estate company she founded, Avalon Group, is 17 years old, and now owns or manages a $300 million portfolio of properties. Her son, Ethan, is 8. Before she had Ethan, says Camp, “No one in their wildest imagination thought I would want to be a mom; I chose to be a mom. And I chose to have my son on my own.”

For her, the challenge of single parenthood from the get-go was also an opportunity to plan with the same deliberation she uses to lay out a project. “By the time I had my child,” says Camp, “Hillary (Clinton) had already defined what a parent should be looking for, and it was a village of support. She said it takes a village to raise your child, and when you become a parent, boy, is that true.”

Camp talked to her three older sisters, whose children are grown, and they agreed to help form the core of caring adults for Ethan. They take the afterschool shift, doing the driving to lessons and practice for Ethan’s six sports. And Camp and her son get many of their dinners from aunties or grandma.

Non-negotiable: Sports games. Camp’s son plays six sports. “I can’t take him to every practice, but I go to every game,” says Camp, “except for the ones on Friday nights, when I have events.”

Tradeoff: Housework. “I knew that I would have dishes sitting in the dishwasher for a week. I knew that I would have laundry piled up for over a month. I knew that housework would be secondary to quality of life activities, and that would be OK.”

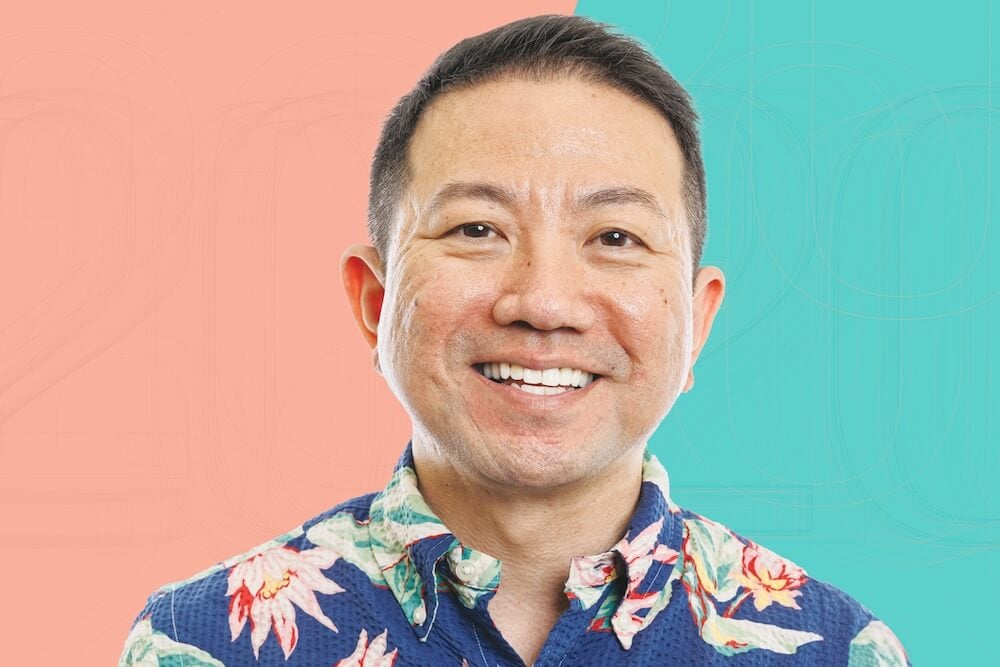

Alicia Moy, President & CEO of Hawaii Gas

Often, the higher the corporate leadership position, the more all-consuming it is. Neither Moy nor her husband, Jake Houseman, have family in the Islands, so Moy says Jake decided to scale back: “He had a successful career as an investment banker in New York, but he made the choice to set it aside so that I could take on this role.”They now hire some help during the week so Jake can help startup companies find their feet. “There are many conversations about how we raise our family, given my work schedule, but every decision boils down to one question: What’s in the best interest of our family right now?” says Moy. That answer will change as their family grows; right now their boys, Kai and Kade, are 3 and 11 months.

Non-negotiable: Seeing her children almost every day. It’s not easy. “When our two boys were very young, we could adjust their schedules to fit mine. I used to leave the office well after dark, and the boys would stay up late so I could spend time with them. Now that my oldest son, Kai, just started preschool, I have had to adjust my schedule to fit his.” For Moy, it means going home for dinner and bedtime when she can, and then hopping online well into the night to make sure deadlines are met.

Tradeoff: “Like most parents, I’ve learned to operate on much less sleep.”

Heidi Kim, VP at Healthways Inc.

Kim is in charge of the Hawaii region of Healthways’ Blue Zones project, which aims to increase life expectancy across the nation through healthy living. In 2014, she was also named national Young Mother of the Year by American Mothers Inc. But even a nationally recognized mom needs a village for her three sons, ages 10, 10 and 14.

“You know what? It’s grandparents,” says Kim. “My parents are an amazing support system.” Kim’s husband, Ed Sniffen, is both a hands-on dad and the Hawaii Department of Transportation’s deputy highways director. Sometimes they divide and conquer: Ed takes Sam to school in the morning, and Heidi takes the twins. Her mother picks them up after school, says Kim, “at the end of the day, when everything tends to bunch up.” At the national Mother of the Year awards, says Kim, “They told me, ‘Hawaii does families right.’ It wasn’t with regard to me, specifically, but the culture does. And I believe it.”

Non-negotiable: Dinnertime and bedtime. “Big things (like events and games) are important,” says Kim, “but also being there consistently, every day, so they know there’s going to be the time that you are there – physically and mentally.”

Tradeoff: Kim laughs and says that on many days, “We eat at eight!”

Heidi Kim’s Village: Grandfather Randy Kim and, from left, sons Eli, Simon (both 10) and Sam (14), and husband, Edwin Sniffen. Not pictured is grandmother Beverly Kim.

Barbra Pleadwell, Partner, Hastings & Pleadwell

Relying on extended family wasn’t an option for communications firm partner Pleadwell and her husband, Jayson Harper, whose families live thousands of miles away. Over the years, she and Harper have crafted a family out of friends, particularly from a baby hui she joined after her daughter Bella Grace was born. “We will pick up each others’ kids, do a sleepover when we need it … my kids are 12, and that mommy network is still working for all of us, big time. They are the rock. They are my ‘grandma and grandpa.’ ”

Pleadwell also says she married the right guy. “He’s my partner,” she says simply.

Non-negotiable: Being available through the teen years, for which Pleadwell says her two daughters need her more than ever. “They’re going through stuff. You get to the high school years, and your kids are going to ditch you pretty soon. So when they’re ready to talk, you’ve got to be right there. ‘Oh, you want to talk? OK!’ It’s been a revelation to me.”

Tradeoff: “After Bella Grace’s friend joined our family more than four years ago, I stopped cooking. I used to cook every night, gourmet stuff. And I just was like, ‘Done with that. I run a business.’ I’ll still cook; just not every night,” says Pleadwell.

Barbra Pleadwell’s Village: Husband Jayson Harper, daughters Amelia (left) and Bella Grace, both 12. Villagers not pictured include many from a baby hui formed when Bella Grace was little.

Amanda Corby Noguchi, CEO of Under My Umbrella and co-founder of Pili Group

Amanda Corby Noguchi is so often seen with her two young daughters (Elee, 2, and Frankee, 1) when she’s out and about that it’s easy to forget that her girls have one of the most extensive villages around. “When people ask me, ‘How do you do it all? How are you a mother who spends so much time with your kids, and a business owner, and active in your community?’ my answer is, ‘I don’t. We do,’” says Noguchi.

By “we,” she means her husband, Mark, co-founder of Pili Group; both their parents; her friend Mariah Gergen (whom Noguchi calls her “corporate wife”); and a host of staffers she considers family.

Noguchi says she and Mark didn’t plan how they were going to combine the all-consuming nature of their work with having kids ahead of time: ‘We pretty much just said, ‘We’re going to keep doing our lives, and they’re just going to be enriched by having our children.’ Is it hard sometimes? Yes. Most definitely, it’s hard. But it’s worth it.”

Non-negotiable: Sharing what she does with her kids. When Elee goes to an event setup, she works right alongside everyone else, says Noguchi: “There’s always something for her to do, whether it’s counting zip ties that are going to be used to hang the banner, or helping move things from one side of the room to the other. Even if they’re made-up jobs, she feels like she’s doing work. She’s part of it. And she likes working.”

Tradeoff: Limiting growth, for now. Even though a full-service restaurant would be considered a next logical step, Pili Group intentionally limits its operations to cafes that are open during the day, and to catering, where they can choose which events they do. And they don’t do Sundays, says Noguchi. “We’ve been asked to do some really cool events on Sunday, and we said, no, we’re going to stick to it. Because if we start to give in once, it’s really hard.”

Amanda Corby Noguchi’s Village:From left: Nitasha Stiritz, event manager of Under My Umbrella; daughter Frankee (1); husband, Mark Noguchi; daughter Elee (2) with Amanda; Mark’s mother, Eleanor Noguchi; Jasmine Gamboa, who started as a babysitter for the girls and is now a part-time employee of Under My Umbrella; and Mariah Gergen, who Amanda describes as “corporate wife, event director and office administrator” for Pili Group and Under My Umbrella. Not pictured are Hideo Noguchi and Keiko Gerstle.

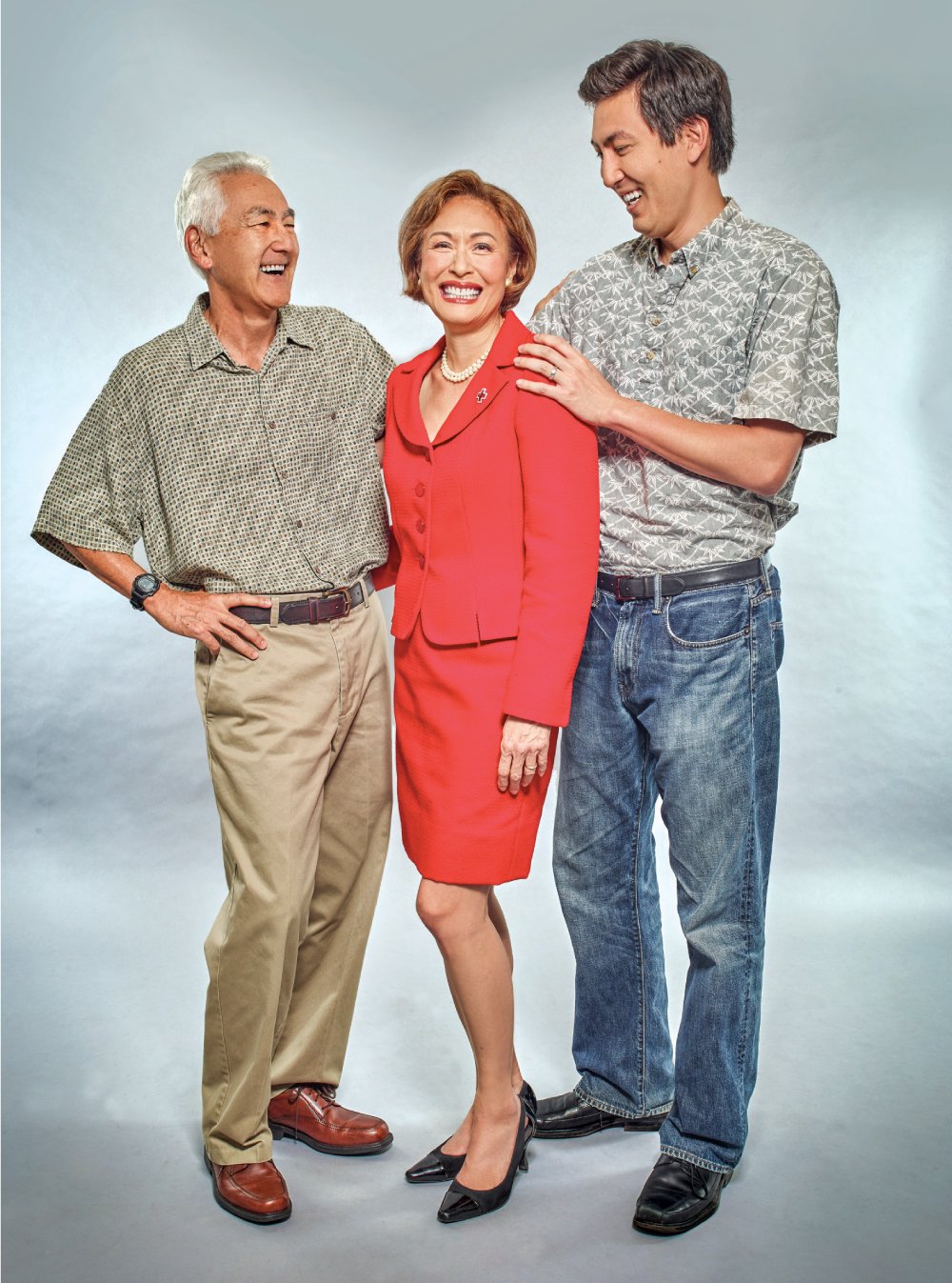

Coralie Chun Matayoshi, CEO, American Red Cross Hawaii State Chapter

At 32, 30 and 27, Matayoshi’s three children are grown, but when they were born, she says, “I was the only woman in the law firm. There were no maternity leave policies. I went down to four days out of five, which meant you work five days a week, but you can leave at 5. Other guys were going to eat dinner and coming back to work.”

Three decades ago, with no road map to follow, Matayoshi handled it whirlwind style: “I sewed all their Halloween costumes, I baked their birthday cakes,” she says. It helped that she loved the domestic side of things. “I used to take my vacation time from the law firm to cook and clean,” she says. “I just blasted classical music. But it’s because I enjoyed it. I wouldn’t say everybody should do that.”

Even then, Matayoshi’s family became “totally a team.” Her husband, Ron, who was working at UH, was the daytime guy: “Ron had a more flexible schedule, so he went to the PTO meetings. He did the coaching.” Matayoshi took the night shift, often cooking, baking or sewing until midnight. And she taught her children early to do their part. “We made it work,” she says. “If you have a team, everybody’s kind of pacing themselves. If you’re doing it by yourself, you’re going to burn out. But if you have a relay team, you can go farther together.”

Non-negotiable: Home-cooked meals. Matayoshi, who loves cooking, cooked on nights and weekends and froze for use during the week. (For other practical tips for parents from Matayoshi, visit this story online at hawaiibusiness.com.)

Tradeoff: When she started having children, says Matayoshi, “I was a litigator. But I started to pull away from litigation, because it’s the most demanding (type of law work). You work on the court’s calendar; it doesn’t matter if your baby has a birthday or whatever, you’ve got to be there. I moved toward more document-based, real estate work.”

Coralie Chun Matayoshi’s Village: Her husband, Ron, and son, Scot. Missing from photo are daughters Kelly and Alana.

Sunshine Topping, VP, Human Resources at Hawaiian Telcom

Sunshine Topping has done it both ways – she opted out of the full-time workforce when she had her first child, and spent seven years consulting part-time. When she went back to work full time, she says, “The conscious decision I made was that when I’m at work, I’m going to do the very best job I can. When I’m at home, I’m going to do the very best job I can, and enjoy it the most that I can.”

The village for Topping’s three children, Kaehu, 13, Hokulani, 11, and Paoa, 6, includes Topping and her husband, Miles, who works at UH as a director of energy management and has “been a 50-50 dad pretty much the whole time.” With parents who have two demanding jobs, it can be a challenge when a child is sick, says Topping: “We’ve done this thing where we’ve handed them back and forth two or three times in a day. It’s an amazing tightrope we walk sometimes.” Both grandmothers pitch in where they can, particularly after school and during school vacations.

Topping, like many working parents, struggles with balance, but says, “I know they say you can’t have your cake and eat it, too, and I suppose that’s true, but I just refuse to give. On either side.”

Non-negotiable: Weekends. “We do everything together on the weekends,” says Topping. “We go to the beach together, we go to (sports) games together.” On Saturdays, they also clean the house together: “My husband keeps trying to market it as a bonding activity, but generally there’s just a lot of yelling and screaming that happens during that time – but that’s kind of what we do. All together. And then we head out to the beach, or whatever thing we have.”

Tradeoff: “I don’t do a lot of going out with my friends,” says Topping with a laugh. “People ask me for happy hour, and I’m like, ‘Oh, my gosh, that would take me two weeks to coordinate.’”

Sunshine Topping’s Village: Daughters Hokulani, 11, left, and Kaehu, 13, and son, Paoa, 6; and husband, Miles. Missing from the photo are grandparents Annie and Richard Byrd, Sunshine’s mother, Carol Helekunihi, and countless friends, aunties and uncles.

Not Just a Women’s Issue

More than one leader-mom we spoke to for this piece raised an eyebrow when they learned it was going into our Wahine issue. “I think my husband has as many good things to say about being a dad as I have to say about communication,” Barbra Pleadwell observes. Coralie Matayoshi says that “as long as men and women are unequal at home, they will not be equal in the workplace.”

In other words, the fact that work-family balance for business leaders is largely considered a women’s issue, is itself a problem. Sunshine Topping was even more frank. “When I was working for the governor, people would ask my husband, ‘Wow, Miles, it’s amazing Sunshine does that, how does she do it?’ And he was like, ‘Well, how do I do it? No one asks me how I do it. I have three kids and work full time, too.’ And I told him, ‘You know, the insult of that question is actually to me, because it implies that it’s completely my responsibility. And it’s not. It’s ours.’ Until that question gets asked equally of us, we have a long way to go.”

The traditional assumption that a male business leader will be married to a stay-at-home spouse is also still alive and well in many sectors of Hawaii’s business community. Several of our leader-mom interviewees couldn’t think of any high-ranking male executives who hadn’t solved the work-family balance equation in the old-fashioned way. And, as Matayoshi said, “It’s easy when you’re at the top and your wife is at home with the kids. It’s solved.”

There was also the feeling of a catch-22: that even if women were expected to be the hands-on parent, they were also more penalized at work for being one. Matayoshi recalled finding a study “that people perceive a man taking off work early or in the middle of the day to watch his daughter at a ballet recital as so endearing – but when women skip lunch and leave early to pick up the kid from preschool before they get fined, that’s (seen as) not having commitment” to the job. But there can also be a career cost to men who request family leave.

And Topping, who is in charge of Hawaiian Telcom’s human resources, felt that change was in the air: “Both (parents) work, and yet still love their children, and want a lot for their children, and want to be there. Creating an environment where that’s not anomalous, where the person who has that doesn’t feel weird, is really important.”

So we asked Topping’s question – How do you do it all? – of dads who try to share the labor of raising a family equally and who are also business or community leaders, including the new executive director of the Hawaii State Ethics commission, Dan Gluck. And then we asked how, if at all, the work-life needle might be moving for people of both genders.

For their answers, and more on how the employment equation is changing for Hawaii leaders who want to be parents, visit hawaiibusiness.com/parents.

“Both (parents) work, and yet still love their children, and want a lot for their children, and want to be there. Creating an environment where that’s not anomalous, where the person who has that doesn’t feel weird, is really important.”

—Sunshine Topping

8 Lessons Learned from Motherhood and Leadership

1. You can’t do it all yourself. But it can all get done.

“You have to remember that you can’t do everything,” says Christine Camp. “Ask for help. You’re going to need to build your village, your support base, and make sure they understand they are going to do this with you. Your husband or wife first, then your parents, and everyone around you. And don’t be ashamed to hire help, to have support.”

2. Accept that there will be compromises.

Alicia Moy says one of her greatest parenting challenges “is missing out on some of those ‘first’ moments. I was running a major event last week, which happened to fall on the same day as my son’s first day of preschool. I had planned to take him on his first day, but I just couldn’t make it work.”

Meredith Ching, senior VP of government and community relations at Alexander and Baldwin, whose daughter, Katherine, is now 19, remembers the feeling well: “I told myself from the beginning: ‘I may not be the one to see her walk for the first time.’ But when I saw her walk for the first time, that was just as good.”

3. Make some sacred spaces, too.

These will be different for everyone, according to your profession, your children’s stages in life and you. Christine Camp has two work schedules: summer and school year.

During the school year, Camp is usually at her desk by 7:30. But when her son Ethan has no school, she tries to start work later, at 9:00 or 9:30, to fit in a morning hangout with him.

Sunshine Topping structures her work life so she’s there for dinner, making sure not to schedule recurring meetings outside of regular work hours: “Of course there are going to be times when I have to work till 10 at night, or a week in a row of really late nights, and that’s OK: as long as I know there’s an end, and I’m not saying, ‘Yes, I’m going to alter my family life, indefinitely, for a job.’ ”

Choosing when and how to respond to communications is another opportunity to draw boundaries that work for both your job and your family. Jayson Harper, husband of Barbra Pleadwell and a VP at American Savings Bank, doesn’t check his email until his work day starts, saying it was a “wake-up call” when his female boss told him, “‘Listen, I’m not going to respond to your emails if you send them on the weekend or some other crazy time.’ ”

4. Show you are committed to getting it done.

“There’s no substitute for hard work,” says Coralie Chun Matayoshi. “You have to show you can be trusted to get the job done, so when you leave at 4 or 4:30 to pick up the kids, maybe you’ll be back on the computer after dinner. It can’t be just, ‘Oh, you’re a mother, you need to take care of the kids.’ That doesn’t really work in business. You have to show you can do the job with flexible hours.”

“Every company has its bottom 20 percent and its top 20 percent,” agrees Camp. “You want to be in the top 20 percent.”

5. Because wthen they know you will deliver, you can ask for flex.

Topping recalls advice she got from her sister, an executive at Bacardi Ltd., who had seen a consultant speak on combining motherhood and leadership: “This woman (consultant) kept saying, ‘You have to be good enough to force your life on people. You have to do good enough work that the concessions you need are not a problem.’ ”

6. Turn your job into a classroom.

“As much as possible, we like to involve the kids so they can see who we are when we’re not at home,” says Heidi Kim. When her husband, Ed, appears on the morning news for his job with the state Department of Transportation, says Kim, “The boys will want to go with him if they can.” And they accompany him to neighborhood board meetings, too, which “spur a lot of conversation: ‘How is it that we contribute to our community?’ ‘How is it that we handle difficult conversations and conflict and discussion?’ ”

7. Blend family and community leadership.

In Hawaii, contributing time and energy to causes you care about is considered an important part of business and personal success, and often your kids can be part of that. “It’s not uncommon for us to bond as a family, going to a community-service project, or going to a board meeting as a family,” says Jayson Harper. Because of that: “We have kids who are going to see their parents involved in doing things that are good for the community, and then, hopefully, it’s part of who they become.”

8. Let parenthood make you a better leader.

“I’m mom in our business, and I’m also mom at home, and the lessons we’ve learned from having kids have been so helpful in how to be better leaders,” says Noguchi, of Pili Group and Under My Umbrella. “It’s not that our staff act like children, but we are the parents. It’s our job to take care of them, to provide them with the best tools to be successful at their job, and to ask, ‘What do they need to best thrive and grow?’ ”

What’s the Best Career Choice for a Parent: Employee or Entrepreneur?

We asked mothers whether the best way to combine motherhood and leadership was to take jobs with companies and organizations or run your own business. Read what they said and join that conversation with this story at hawaiibusiness.com/parents.