Urban Gardens Grow Food & Raise Consciousness

The Manoa community gardens sit in the center of the valley, with the Koolau rising around them like the sides of a deep, green bowl. On one bright, blue morning, Katherine Carreira dug up nut grass, turned clods of clay and exposed red earthworms in a 10-by-20-foot plot filled with rows of kalo, basil and chives. “There is something about the soil that calls to me,” Carreira says, but she has no backyard garden because she lives in a condo. Like the 1,247 other urban gardeners who tend plots in 10 community gardens across Oahu, Carreira wants to grow her own food and be part of a larger community.

“There’s only so much food that can be grown within the urban core, which is why we need to protect our ag lands from development.”

– Nate Ortiz

A few yards away, another gardener wrestled lilikoi vines. Nicole, who declined to give her last name, cautioned against publishing the garden’s location, explaining, “We get a lot of thieves.” Nevertheless, she cheerily provided a tour of the 91 plots, each square with its own personality. One overgrown block belonging to a ceramist is filled with sculptures: a white glazed chicken perches on a pomegranate tree and a large urn decorated with images of Indonesian farmers stands beside an edible hibiscus bush (the purple leaves taste like tamarind).

Nicole warned that joining the Manoa community gardens brings both rights and responsibilities, and that people shouldn’t treat the rented spaces like their backyards. Members vigilantly uphold communal rules, which include paying monthly dues and attending monthly meetings. It means not growing plants that might shade or send roots into adjacent plots, and keeping your children out of other people’s gardens. Violations can result in the loss of your plot. Gardeners communicate with each other by leaving notes in the plastic jars weighted with stones that sit in each plot.

The community gardens in Makiki District Park have another rule: You can’t sell anything you grow there. Marianne Rho, who spent a year on the wait list before getting her fenced 10-by10-foot plot, says most of the Makiki gardeners are in their late 60s or 70s. Before moving to a nearby condo, Rho lived on a one-acre property on the Big Island. She misses her backyard and now comes to the community garden every other day for about 30 to 40 minutes to weed, water and tend her asparagus and other plants. Rho says many of her fellow gardeners speak little to no English and appear to grow “the herbs and vegetables from their home countries.”

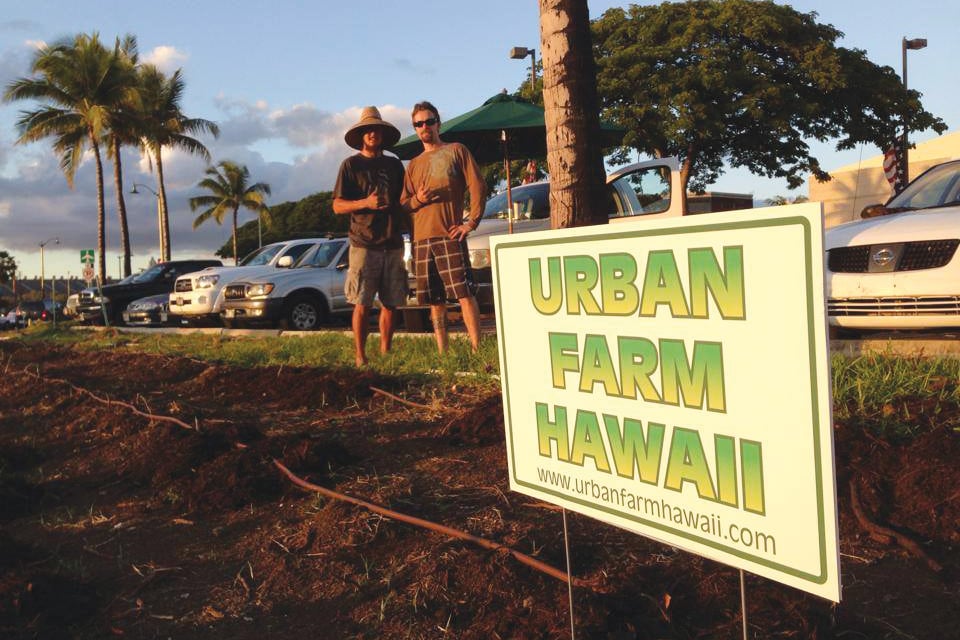

If community gardens are urban farming writ small, Urban Farm Hawaii has bigger goals. In January 2014, co-founders Nate Ortiz, Mitchell Loo and Andrew Dedrick planted 654 cuttings of dry-land taro on a Kamehameha Schools site at the corner of Ala Moana and South Street.

Before he was an urban taro farmer, Ortiz says, he was active in the campaign to block agricultural land on the Ewa plain from being turned into the Hoopili housing development. As a senior at UH-Manoa’s College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, “I got tired of skipping classes to go down to the Capitol to try and change ag policy. Now, I’m trying to change minds,” he says.

“There’s only so much food that can be grown within an urban core, which is why we need to protect our ag lands from development. But I realized that most people who live in Honolulu don’t visit farms – they travel from the suburbs to downtown.” Planting a mala, or dry-land taro patch, in the middle of Kakaako became a way to expose people to agriculture.

Ortiz says it worked. “I had bus drivers pulling over to the side of the road, with passengers aboard, asking, ‘Eh, what kind of kalo are you growing?’ Pedestrians would walk by and ask us about gardening,” says Ortiz. Kalo takes nine to 12 months to mature, and KS had to clear the mala after only eight months to make way for development of The Collection condos. Fortunately, KS was pleased with the nonpofit’s work and leased it a quarter-acre strip across from the John A. Burns School of Medicine.

Ortiz now works as the garden coordinator at the Institute for Human Services homeless shelter, where he tends the garden plots surrounding the shelter in Iwilei and is redesigning its rooftop garden. He is also using the gardens to help the shelter’s guests grow. Gardening requires observation skills, creative problem solving and attention to detail, he says, and he teaches basic job skills through gardening. “If someone also realizes they love farming, and this is what they want to do, I’m here to guide them in that direction as well.”

How to Get a Plot

To apply for a plot, interested gardeners should:

1. Attend a garden meeting at their chosen location.

2. Fill out an application at the meeting.

3. If no plot is available, applicants will go on a waiting list and must attend subsequent meetings. You need to be present at the meeting to get a plot.

For garden locations and other information visit:

www.honolulu.gov/parks/hbgcommunitygardens.html or use this shortcut: tinyurl.com/osgp5kg.

www.urbanfarmhawaii.com