Child Care: Unaffordable and Unavailable

Part II: The Solutions

A lack of access to affordable child care doesn’t just hurt working families. Each year, businesses nationwide lose about $4.4 billion due to employee absenteeism that results from a breakdown in child care, according to a 2017 report by Child Care Aware of America.

More child care would also benefit businesses, the report says, because parents could work more flexible hours and more mothers could join the workforce.

Local workers identify child care as an issue, says Melissa Pavlicek, executive director of the Society for Human Resource Management’s Hawaii chapter. She cites an informal survey the chapter did in December 2017: Over 70 percent of the chapter’s members said child care was an issue for their employees and that problems revolved around issues like affordability, availability and trustworthiness of providers.

Some employers are stepping up to be part of the solution.

“It’s infrastructure, same as housing is and roads are and health care benefits,” says Zysman, of the Hawaii Children’s Action Network. “The Millennial workforce has children. If we can’t make it affordable and high quality for them, they’re going to leave.”

BENEFICIAL FOR ALL

The 2017 report by Child Care Aware of America says both parents and employers benefit when businesses help their workers with child care. Benefits include fewer missed workdays and lower employee turnover.

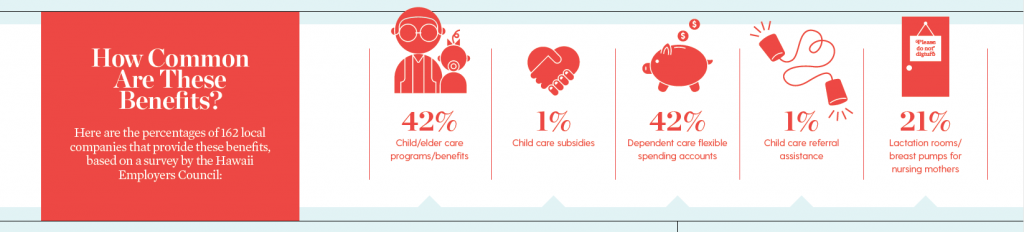

Support can come in many forms: dependent care flexible spending accounts, subsidized child care, backup child care, paid family leave and on-site child care.

“There’s no question that we need these things,” Zysman says. “They’re good for kids and they’re good for families and they’re good for employers. The question is more like, ‘How do we find the money?’ ”

For a small business like Hawaii Diagnostic Radiology Services, helping its employees with child care means getting creative, says Cathy Okinaka, the company’s HR director.

Several employees did not have consistent child care, so the company provides backup child care at its Kaheka location, where children can be watched by Okinaka if working parents have no other option.

The company also allows parents to use sick time to care for their children, offers flexible spending accounts that allow employees to set aside pretax income for dependent care expenses, and is flexible in temporarily adjusting work schedules and statuses to meet employee needs.

“We’re a small company. We can’t have super elaborate benefits, so we try to do things that make life easier. … We would love to give everybody long-term disability and those things that larger companies do, but this is just another way to help,” Okinaka says. “I think people appreciate it.”

Other benefits that may help employees include referrals for child care and a central database where employees can exchange ideas and referrals, both of which simplicityHR by Altres provides to its clients, says Michele Kauinui, Altres’ director of human resource services.

Removing barriers to work, like problems with child care, can make for happier, more productive workers. Carolee Kubo, director of the human resources department for the City and County of Honolulu, says the county aims to be a model employer in the delivery of child care services to its 10,000 employees. Some services include generous paid leave and holidays, flexible spending accounts, flexible schedules, a program that lets employees donate vacation leave to other employees, and a child care center near Honolulu Hale where county employees’ children get priority on the waitlist.

SUPPORTING EMPLOYEES

Jabola-Carolus, of the Hawaii State Commission on the Status of Women, took a three-month leave after she gave birth – longer than most mothers get in Hawaii and around the U.S. For the past decade, her commission has pushed for paid family leave for all new parents, which would help them save on child care and provide them with more time to bond with their babies, says Jabola-Carolus.

This year the Legislature attempted to lay the groundwork for a paid family leave program. The legislation, which at press time was pending the governor’s approval, was authored by state Sen. Jill Tokuda and required an analysis to be conducted to shed light on the impacts of establishing a paid family leave program on employers, employees, consumers and caregivers.

Several organizations testified against the measure. Pavlicek, of SHRM Hawaii, says her organization requested that legislators not mandate certain types of leave. Employers should have the flexibility to figure out what works best for them and their workers, she says. Other organizations, like the Chamber of Commerce Hawaii, cited concerns with the impact paid family leave would have on the already high cost of doing business.

Some local employers, like Project Vision Hawaii, already offer some form of paid family leave, saying the benefit helps recruit and retain good employees. Elizabeth “Annie” Valentin, the executive director, says providing eight weeks of paid maternity leave is an investment in the nonprofit’s staff and their lives. So far, two new mothers, including herself, have used it.

Vincent Kimura, CEO of Smart Yields, agrees. His company provides three weeks of paid family leave for new parents and caregivers, and he says it’s especially important to provide support for employees in a state where many people end up leaving if they can’t afford the high cost of living. “If we’re not going to increase the wages for, say, teachers and other people, then we need more support services so they can do the jobs they want to do and then ultimately support the companies that are paying them,” he says.

ProService Hawaii, a human resources solution company with 260 internal employees, offers 12 weeks of fully paid parental leave to mothers and fathers for the birth of a new child or the placement of a child through adoption or foster care. ProService Hawaii can do so because it has enough workers to plan for and accommodate an employee’s absence, says Trisha Nomura, who until recently was the company’s chief people officer.

TWO BIRDS, ONE STONE

Kualoa Ranch employees who can’t find child care nearby are often forced to quit and stay at home with their children. The alternative is to drive long distances to child care before driving to work, says Carri Morgan, whose husband owns the ranch.

That’s why she is working on a plan to establish an on-site child care center. Her vision is a center rooted in nature-based education, with staff who are experts in inquiry-based learning. The ranch has the space and resources to build a center, she says; the biggest challenge will be finding the teachers to staff it.

Windward Oahu needs more child care, she says, so she hopes Kualoa Ranch can be a model for other businesses to establish their own centers: “We all need to be part of the solution to Hawaii’s high cost of living and what that means for young families. So, I’m hoping that if we do this other businesses will do it as well.”

On-site child care centers are rare in the Islands. When asked, sources for this story could only point toward those at UH campuses, Castle Medical Center, the Prince Kūhiō Federal Building and the Honolulu Civic Center.

Eva Moravcik, an early childhood professor at Honolulu Community College, which runs children’s centers on campus and at Kapiolani and Leeward community colleges for keiki of full-time students and employees, thinks most employers are not willing to have an on-site child care center because it’s a business in itself.

This past legislative session, Tokuda tried to incentivize employers by proposing a state tax credit for establishing and maintaining a state-licensed and nationally accredited early childhood facility. She says this would essentially kill two birds with one stone: The effort supports healthy workspaces and addresses the shortage of child care openings. The measure died.

Leilani Au, director of the Children’s Center at UH Manoa, says employers who want an on-site center have to decide whether to contract with someone else to run the center, and what the space and resource needs are.

She says many existing child care centers are subsidized: They might be part of a church that charges little or no rent, they might provide teaching services for the university or they might be part of a chain with economies of scale.

“If an employer wanted to have a child care center, they couldn’t look at it as a way to make money,” she says. “So if they were doing it to help their employees and it’s not full – like what if their employees don’t have babies this year – so then would they keep paying for it if it wasn’t self-sufficient?”

Lisa Uyehara, director of Seagull Schools’ Early Education Center, says employers sometimes have to open their doors to children of nonemployees to fill slots. That’s what the Early Education Center did after it opened at the Honolulu Civic Center in 1986. Today, about 15 to 20 percent of its enrollment are keiki of county employees.

BALANCING ACT

One challenge for employers is fairness, says Kauinui, of simplicityHR by Altres. While some employers want to support child care options, they may also feel they need to provide equivalent benefits for people without children.

“I think for every employer it’s a very individualized solution that works best. What is the demographic of your workforce? What works best for your business? And what can you afford to do financially?” she asks. “I think with the unemployment rate being what it is right now, employers are forced to think outside of the box and find ways to attract and retain qualified employees.”

Employers also have to consider the costs of benefits. Dependent care flexible spending accounts, for example, take a small investment to maintain, she says, much lower than, say, medical insurance, but it’s still a cost and burden, especially for smaller businesses.

EVERYONE HAS A ROLE

Support for child care comes from many organizations. This summer, Parents and Children Together opened a day care center and preschool at Kahauiki Village, the community that houses formerly homeless families near Sand Island. That center will serve about 35 resident keiki ages 6 weeks to 5 years. Ryan Kusumoto, president and CEO of PACT, says organizations like his locate early education programs within public housing projects to support families that need these services.

The City and County of Honolulu mandates that master planned communities – such as those in Kapolei, Ewa by Gentry, Ko Olina, Hoopili and Royal Kunia – set aside space for child care facilities, says Pamela Witty-Oakland, director of the county’s Department of Community Services, which issues requests for proposals to find providers to run the facilities.

That mandate has been in place since 1989, and one trend the department sees is schools – both public and private – building their own preschools. Child care, she says, is becoming recognized as an important component of any community.

Tokuda thinks everyone has a role to play in helping families to afford and find child care: “I don’t think government can do it by itself, and I think everyone has to recognize the positive contributions that we can make toward supporting workers and their families in many different ways, whether it’s paid family leave, whether it’s child care, early learning,” she says.

“And if we start doing it together and we start to balance out all of these forks, at the end of the day it’s going to reap benefits for the community.”