Child Care: Unaffordable and Unavailable

Part I: The High Cost and Shortages

Child care is too costly for many working families and there are too few openings for all the children who need proper care. We examine the problem and the responses, including efforts by employers who are part of the solution.

When Summer Yadao had her first child, she stopped working for four years while her then-husband supported the family. Had she continued to work, she says, her entire take-home pay would have gone toward child care for her son. Plus, she couldn’t find a provider she trusted.

Today, as a single mother of three children ages 13, 11 and 2, she can’t afford to stay home with her youngest.

Neither can many other parents. Like Yadao, they need child care so they can work, but the cost of proper care may eat up most of what they would earn.

THE REALITY

State Sen. Jill Tokuda, a mother of two boys, remembers the reality check when she and her husband began paying both of their sons’ preschool tuitions at the same time.

State Sen. Jill Tokuda, a mother of two boys, remembers the reality check when she and her husband began paying both of their sons’ preschool tuitions at the same time.

“You have to start looking at reshuffling everything at that moment,” she says. “You have to start looking at how do you manage your money, and we had to make some really tough decisions on how to make sure that we could afford it, too. And it was a real struggle.”

That’s a reality for many families, including that of Khara Jabola-Carolus, executive director of the Hawaii State Commission on the Status of Women. Before her son turned 2, the tuition for children his age at a child care center was $2,200 a month.

“There were many times at the beginning of the month I would be scared or rushing in and trying to avoid the staff because I couldn’t pay on time,” she says. “And I’m so class privileged compared to most workers in Hawai‘i. … We have to have a solution.”

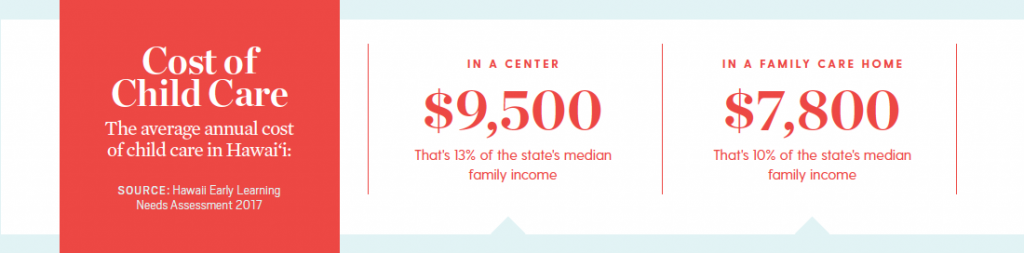

In 2015, Hawaii ranked as the least affordable state for center-based care. The average cost to enroll one child in a child care center, full-time, was $9,500 a year, taking up 13 percent of the state’s median family income, according to the Hawaii Early Learning Needs Assessment that was published by the UH Center on the Family in 2017. The national recommendation is that child care for all children combined takes up no more than 7 percent of a household’s income.

A family child care home is slightly more affordable at an average of $7,800 a year for one child, while infant care at a center exceeds $13,000 a year.

THE STRUGGLE

Subsidies are available from private providers and the state, but many families make too much money to qualify. About half of Hawaii’s households are considered “ALICE” or below. ALICE is an Aloha United Way acronym that stands for Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed: working people who cannot afford the state’s cost of living and have minimal or no savings in case of emergency. ALICE households earn more than the federal poverty level but not enough to afford a basic household budget that includes housing, health care, child care, food and transportation. In Hawaii, the ALICE threshold for a single adult is $28,128 in annual income; for a family of four, the threshold is $72,336. That’s not far off the median household income in Hawaii – $74,511 in 2016, according to the state Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism.

Says Deborah Zysman, executive director of the Hawaii Children’s Action Network, which commissioned the Early Learning Needs Assessment: “They’re the ones that are living paycheck to paycheck, and an even higher percentage of their wage is going to things like child care because they don’t qualify (for subsidies). … The priority had always been start with the lowest income … but we have this huge other group of families that’s struggling to get by.”

A majority of the preschool students at the Waikiki Community Center come from low- to moderate-income families, says center president Caroline Hayashi, and they often need state subsidies to afford tuition.

Hayashi remembers her first year at the center in 2013 when funding for state subsidies decreased. Enrollment dropped from 100 keiki to 35. The school has since raised private foundation funds to help its families and today about 65 percent of its students receive tuition assistance through the center or the state.

Child care providers must balance running their businesses while not pricing out their families, Zysman says, adding that Hawaii doesn’t see as much support from government or corporate funding as some other states, to make child care more affordable.

There are free or inexpensive child care programs, such as family-child interaction learning, public preschool, Head Start and Early Head Start programs, but they cover only a small fraction of the families that need them. But children need proper care because their early years are foundational for lifelong learning and well-being, Zysman says.

A SHORTAGE

If the high cost wasn’t enough of an obstacle, the Islands have a shortage of child care openings. According to Child Care Aware of America, Hawaii has about 66,000 children under 6 years old with two working parents, but the state only has 35,600 regulated child care seats – enough to serve only half of those children.

And care has to be age appropriate – infants need different care than 4-year-olds – with a severe shortage for the youngest children. There are 37,000 children under 2 years old and only 3,900 state-regulated child care seats for this age group.

“So even if there’s money, we don’t have enough child care providers in our state,” Zysman says, adding that money needs to be invested in workforce development to get more early education teachers trained and make child care a worthwhile business for those running it.

Dana Balansag is the administrator for the state’s child care program that licenses facilities and runs two subsidy programs. She says the minimum requirements for health and safety and for provider training sometimes deter private child care homes and centers from becoming regulated facilities. She adds the state is trying to find ways to better support providers through the rigors of getting licensed.

Meeting the need is a multimodal effort, says Lauren Moriguchi, director of the state Executive Office on Early Learning, which runs a publicly funded prekindergarten program. Next school year, the program will serve 520 students across 26 classrooms on 24 campuses – enough to cover about 1 out of every 43 of the state’s 4-year-olds.

Moriguchi says she wants to expand it – especially to help families who are at or below 300 percent of the federal poverty guideline, which is an annual household income of $86,610 for a family of four. The obstacles to expansion include developing the workforce to staff it and affording the costs of facilities, salaries and supplies. Space is limited on public school campuses. Building a portable classroom would cost an estimated $1.5 million – and that number doesn’t include things like plumbing, utilities, fire safety devices and handicap accessibility – and operational costs are estimated to be upward of $134,000 per year.

A shortage of available seats makes it much harder to find a child care provider that meets a parent’s particular needs. Veronica Bond, a 41-year-old single mother of a 3-year-old, says she struggled to find a provider that was close to her job in Waikiki and that stayed open beyond the normal workday. Waikiki Community Center’s preschool, where her son is now enrolled, was the only one she found that met those criteria.