Transformers

As revenues fall and old ways fail, a Hawaiian Electric team tries to turn a power behemoth into a clean-energy matrix.

“You can’t run an operational company like this without leadership that’s experienced in operational issues,” says Robbie Alm, executive vice president for Hawaiian Electric Co. “That’s not me. That was never going to be me.”

Alm isn’t being modest. He’s trying to explain the origins of the Clean Energy Team, a small cadre of company engineers, planners and policy wonks who are behind the greatest corporate transformation the Islands have seen in decades. The changes began two years ago, Alm says. That’s when the utility signed the historic Hawaii Clean Energy Initiative (HCEI) with the governor, and agreed to some audacious goals, including a legal commitment that, by 2030, 40 percent of its power generation would come from renewable energy.

It was the technological, structural and regulatory challenges of meeting these goals that gave birth to the Clean Energy Team. But Alm believes that the leaders of this group, 10 mid-level managers and young vice presidents, will lead the company far into the future. He also believes one of them is likely to be its next CEO.

How it Started

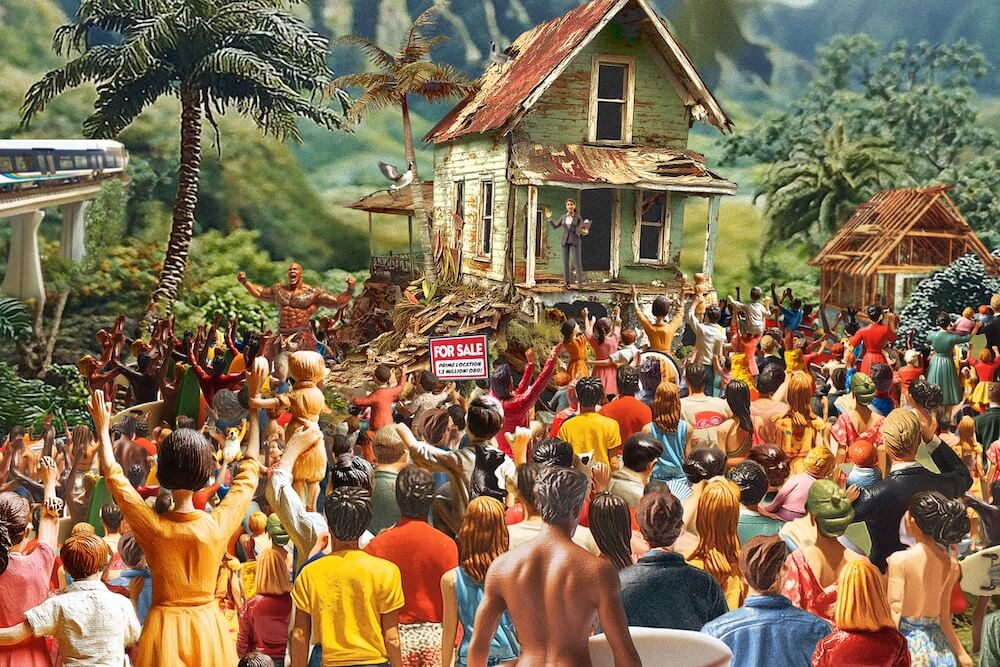

In the years leading up to the Clean Energy Initiative, HECO (along with its Neighbor Island partners, MECO and HELCO) found itself increasingly beleaguered. Its public image had been battered by a series of highly publicized conflicts over issues like the construction of transmission lines on Waahila Ridge and the expansion of power plants at Kahe and Keahole. There was also a sense among the public that the company’s existing clean-energy programs were just empty gestures. “The company found itself in fairly unhappy straits,” Alm says. “The editorial writers were against us, the Legislature wasn’t happy about us, and the environmental and historic preservation groups were against us.”

The company also had built-in financial problems. As HECO chair Connie Lau points out, the company’s efficiency programs and changes in technology meant that even when the economy was expanding, and costs increasing, sales declined steadily. In fact, net revenues have declined in each of the last six years. And, as Lau notes, although the company is allowed by statute to earn 10 percent profits, by 2008 they had fallen below 4 percent.

“If you look at the late 1990s,” says Alm, “we were kind of booming. By the 2000s, though, the economy’s not doing so well. The stock market took that tech dive, interest rates went way down, and we hadn’t been in for a rate case in quite awhile. Financially, the company was challenged. And we weren’t helped at all by being so unpopular with the public. People used words like ‘arrogant,’ ‘monolithic’ and ‘oil-addicted’ to describe us.

“And then, Linda Lingle comes in,” Alm adds, “and she clearly doesn’t like us. If you go back and read her speeches, particularly those leading up to the 2006 legislative session, we were sort of public enemy No. 1. Again, it was our addiction to oil and unwillingness to change.” It wasn’t just idle complaining; the Lingle administration was clearly taking Hawaii’s dependence on fossil fuels seriously. “So, in the 2006 legislative session,” Alm says, “she had those big bills to alter the playing field. And a lot of it passed.”

Maurice Kaya, the former state energy administrator and one of the original authors of the HCEI, points out that some of those laws were transformational. “One,” he says, “was the recognition that the efficiency programs, which were run by the electric utility, were sort of the fox guarding the henhouse. So that was taken away from them. In that same context, we were able to convince the Legislature that there was really no business motivation for the utility to change their ways and get off oil.” In short, Kaya paints a picture of a company financially and structurally unprepared for a clean energy future. It was hard to avoid the perception that the 109-year-old utility was in decline.

So in 2007, when Kaya and Bill Parks, the Department of Energy official who helped write the HCEI, came to Alm with a proposal to radically transform the state’s energy system, it’s not surprising that the utility was interested. In the fall of 2008, after its due diligence, Hawaiian Electric signed on. All that was left was the execution.

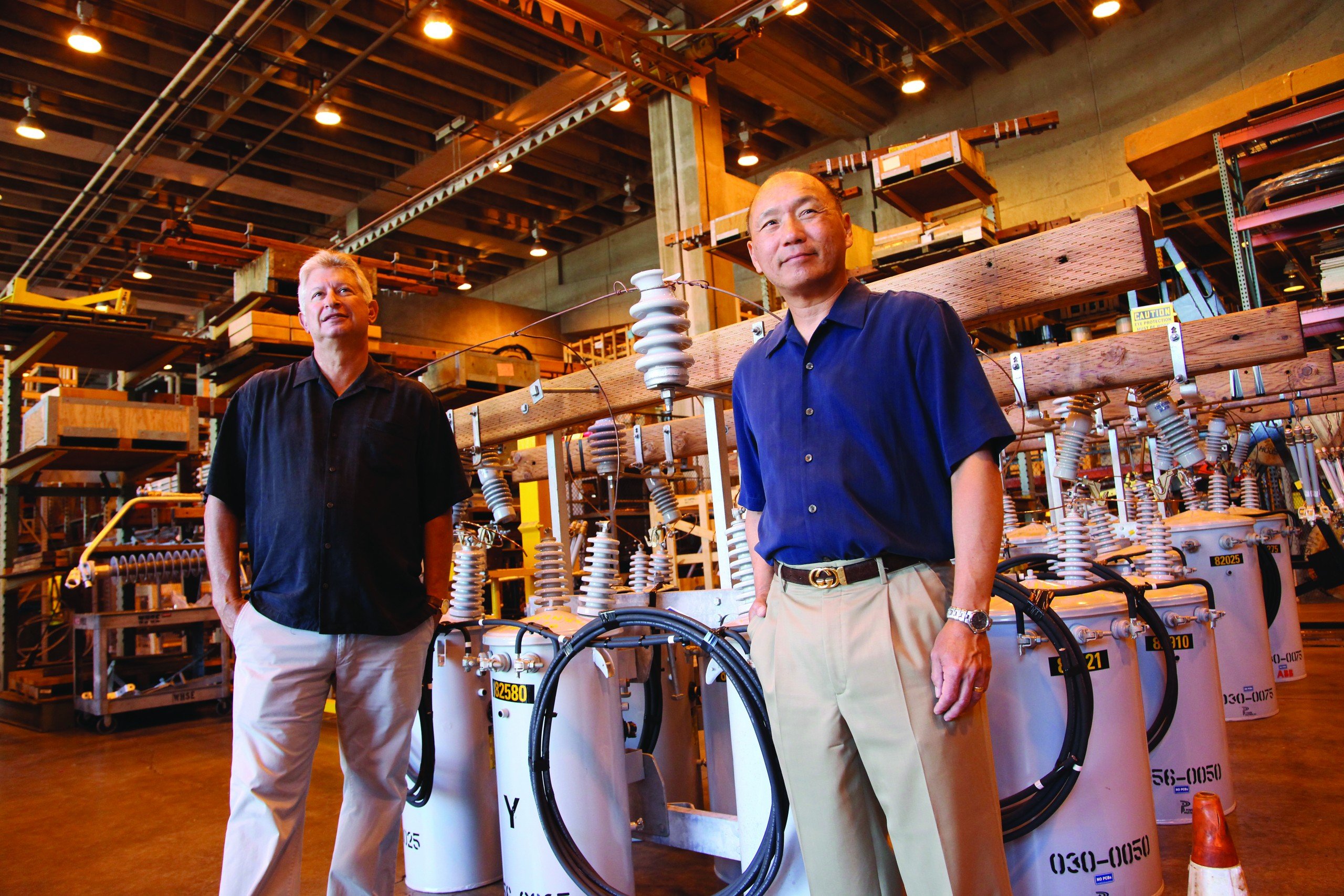

Dan Giovanni (left) and

Robert Young | Photo: Rae Huo

Operations Team

The nuts and bolts of utility work are in operations. That’s what happens in the big power plants, on the vast networks of transmission lines, on the distribution grids that feed electricity to the customer, and in the master control room that oversees it all. Operations is also usually the lair of the most conservative, risk-averse engineers.

At HECO, though, operations is a hotbed of experimentation. It’s the crucible for the schemes and analyses of planners. It’s where the formulations of policy makers and regulators are put to the test. It’s also the site of a remarkable little research and development program into the use of biofuels in traditional steam generators. It’s a good thing, too, because renewable biofuels are a critical part of the company’s clean-energy plans, and it’s hard to see any of those plans without the strong support of operations.

Photo: Rae Huo

Dan Giovanni

Age: 62

Title: Manager, Generation Department

Clean-Energy Responsibilities: Conducting R&D and developing operational plans to convert HECO’s existing fleet of generators to use biofuels.

“The devil’s in the details,” says Giovanni, explaining some of the difficulties of converting from fossil fuels to biofuel. “It means a lot more than asking: ‘What’s the price?’ ‘Does it meet sustainability criteria?’ ‘Can we get it here in time and in volume?’ Those are the simple questions.” The more important questions, at least for an operations guy like Giovanni, are the technical ones. “ ‘How will it behave once we commit to it operationally within our infrastructure?’ ”

Giovanni is leading the utility’s own little R&D program into that question. “We’re going to take one of our largest and most important generating units and operate it for a month on biofuels – 30 days, 24/7. It’s a $12 million test: $5 million worth of equipment, $5 million worth of biofuel, and about $2 million worth of experts from around the world to do the testing and analysis. They’ll look at the environmental impacts, the combustion impacts, the thermal and performance impacts, and the fuel stability question. There’s no shortage of technical questions. But I can tell you this: Six months from now, our team will be the most informed people in the world on how to use biofuels in a conventional steam power plant.”

Photo: Rae Huo

Robert Young

Age: 55

Title: Manager, Systems Operations

Clean-Energy Responsibilities: Run the operations center so the grid can reliably incorporate the most renewable energy possible.

Part of the idea of the Clean Energy Team is the inclusion of operations guys like Young and Giovanni in the mix. Like all the engineers on the team, they have a fundamental grasp of the tension inherent between adding more and more intermittent energy sources, like wind and solar, and maintaining inexpensive, reliable power for customers.

“There’s this conflict,” Young says. “We have to protect the system, but we know that if we don’t do anything, eventually we’ll be subject to higher and higher fuel prices that will drive the cost of electricity up.” He points out that this tension chaffs the fundamental conservatism of engineers.

“Being in operations, I’d like to see more stable resources,” he says. Like Giovanni, he sees biofuels as a critical part of dealing with the intermittency of most renewables. “The fallback really is that some generation sources have to burn some form of fuel. Biofuel is a way to get off crude oil.” And Giovanni’s research program has provided him some hope for clean energy.

“In the beginning, there was a pretty high level of anxiety for us engineers,” he says. “The unknown is always daunting. But, from the operating side, as we’re working through things, the comfort level is getting better.”

The Planners

For nearly 100 years, the basic model of an electric-power utility has been relatively simple: Produce electricity in power plants and send it to customers through transmission and distribution lines owned by the utility. If customers need more electricity, fire up another generator. If demand drops, reduce production. This model fit well with the physics of electricity, which require that production and demand move in unison.

But the clean-energy future is less predictable. It’s going to include generation, like wind and solar power, that can’t be fired up at will, and won’t be controlled by the utility anyway. The same opacity will apply to customers as well, many of whom will generate some of their own power. This intermittent, unpredictable power is the bugbear for modern utility engineers, whose principal objective is to produce reliable, high-quality power for their customers.

Some of the key players on the Clean Energy Team are the planners who struggle to cope with this conundrum. It’s their job to design the systems and acquire the resources that will allow the company to integrate ever more renewable energy sources onto the grid without the customer – that’s you and me – even noticing.

“The company will be rewarded for encouraging conservation and adopting more renewable-energy sources.”

Photo: Rae Huo

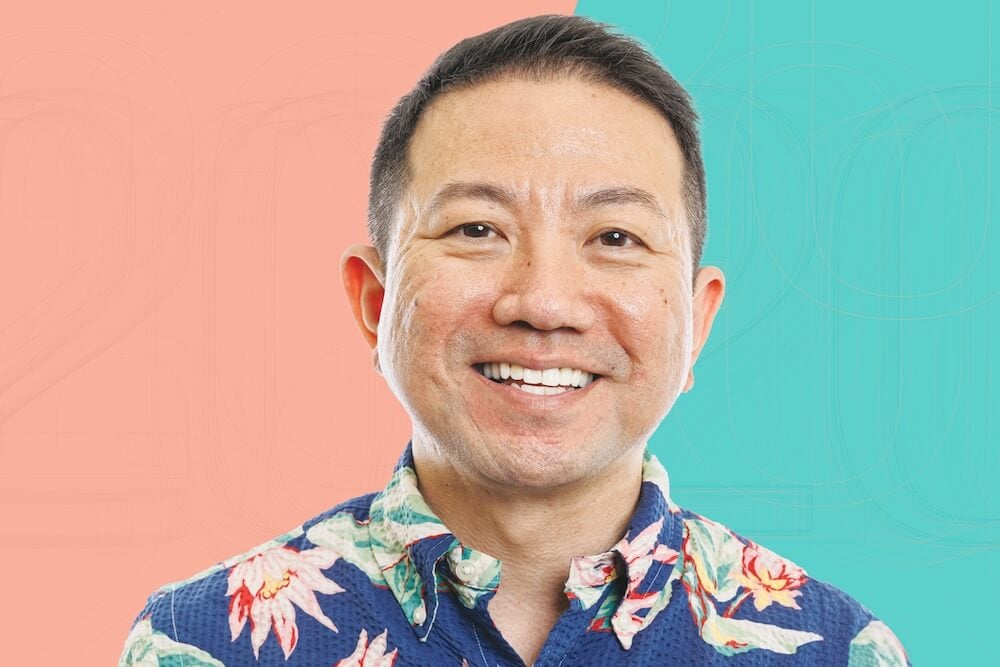

Colton Ching

Age: 43

Title: Manager, Corporate Planning

Clean-Energy Responsibilities: Long-range planning to ensure the company has the generation, transmission and program resources to meet its renewable-energy goals and maintain reliability.

“My group has a hodge-podge of responsibilities,” Ching says. “Part if it is internally focused: We do strategic planning for the company. That includes a lot of internal reporting and risk assessment. But the other half of my department is externally focused: planning – we’re talking 20-year planning – related to long-term use of resources in the system. What are our future needs going to be for transmission? For new generation? What kinds of new demand-side management programs should be deployed? And, most important, how would those resources work together so that we can develop some long-range plans to serve our customers?”

Ching describes how the work of his group dovetails with the work of Leon Roose and Scott Seu, the other key planners on the Clean Energy Team. “I’m going to oversimplify this, but the real focus of Leon’s group is to look at the integration of these new resources on our grid, to look at the math, science and actual day-to-day, minute-to-minute, second-to-second type of solutions to answer the question of how you connect a large wind farm or a lot of PV (photovoltaic solar) power to the grid. How do you make use of their energy, but maintain reliability to the customer. It’s very technical, very focused on shorter time frames.

“My planners look at a broader time scale – from an hours perspective up to a multiyear perspective. And because our time frames are so different, the tools that we use and the analyses we perform are very different. But Leon and his folks and me and my folks, we’re literally joined at the hip. Because we have to look at all these time scales when we plan our system.”

Ching also notes that members of the Clean Energy Team have a responsibility to help change the culture within the company. “Aside from the technical, operational and planning things that all of us are tasked with, we have to affect that sort of change in the rest of the employees as well. We’re the saints that have to spread that gospel.”

Photo: Rae Huo

Leon Roose

Age: 44

Title: Manager, System Integration Department

Clean-Energy Responsibilities: Analyzes the potential effects of integrating new renewable-energy sources into the grid, and develops implementation strategies using technologies like the inter-island cable, smart grid and advanced metering systems.

Roose’s role on the Clean Energy Team is to figure out what it will take to add new, renewable generation to the system. That turns out to be much more complicated than it seems. “Some people think: ‘It’s a small island system; it must be simple,’ ” Roose says. “But it’s completely the opposite. When you’re a small grid, the physics of electricity are actually more complex, because it’s easier to upset the grid when a small disturbance happens.” It’s his job to make sure that doesn’t happen.

It helps that over the years he’s held most of the planning positions in the company. Now, with systems integration, he is responsible for transmission planning and generation planning. “And I’ve added to those functions the planning for what we call our distribution grid,” he says. “Which means I’m responsible for system protection. That’s how we put in relays and other things on our lines so, when you have a problem, it protects the equipment as well as the public.” These kinds of devices and strategies are also going to be a big part of the smart grid, he says, and that’s the real future of integrating the dramatic amounts of renewables on the grid.

Photo: Rae Huo

Scott Seu

Age: 44

Title: Manager, Resource Acquisition Department

Clean-Energy Responsibilities: Using tools like power-purchase agreements and feed-in tariffs to negotiate and purchase as much renewable energy as possible.

If it’s Roose’s job to figure out how to integrate renewable energy sources onto the grid, it’s Seu’s to actually go out and buy it. That means everything from putting out the requests for proposals and negotiating the power-purchase agreements, to actually administering the contracts. It’s a remarkable commitment to clean energy. “People say ‘seamless,’ ” Seu jokes, “But we’ve still got a few seams to work on.”

In many ways, the leading edge of the clean-energy future is the relationship between the utility and the independent wind farms and photovoltaic arrays and other renewable-energy sources that the HCEI envisions. As Seu points out, feed-in tariffs will help to formalize that relationship, and he’s been a key member of the negotiations on the docket now before the PUC. “As we got into details,” he says, “it quickly became about much more than just distribution issues. It got into talking about all the details of how you develop contracts for renewable-energy resources.”

After all, one of the principal tenets of a feed-in tariff is that the price of these new sources should no longer be tied to the price of oil. “So what should be the appropriate price?” Seu asks. “We want to come up with a fare that will be fair to the developer and pay them a reasonable profit. Yet, at the same time, all that is going to be paid by our customers.”

His point, though, is clear: “I don’t think we’re ever going to build a brand new fossil-fuel power plant again.”

Photo: Rae Huo

Ron Cox

Age: 53

Title: Manager, Energy Solutions Department

Clean-Energy Responsibilities: Help customers minimize energy use and reduce their bills through programs like demand-side management and the application of advanced technologies.

Although renewable-energy sources, like solar, wind and biofuels, may seem sexy, in the short term, conservation and greater efficiency will likely play a greater role in helping the state reach its clean-energy goals. It’s Cox’s role to expand and reinforce programs like Energy Scout that help customers reduce the energy they need from HECO.

But like many on the team, Cox brings a breadth of experience that’s invaluable in the group’s customary give and take. He came to the utility after a career in the nuclear Navy. “My first year with the company, I was in operations doing strategic planning,” he says. Then he moved into power purchasing and fuel contracts, including going through the regulatory approval process for critical issues, like biofuels. In fact, this expansion of responsibilities gets to the heart of the Clean Energy Team, Cox says. “This is just the recognition that we needed to make some organizational changes. Today, we literally have three managers doing what I used to do. One manager does nothing but buy biofuels, another manager does traditional fuels and another does power purchase contracts.”

According to Cox, this is a sign of the company’s commitment to clean energy “We’re out there on the leading – sometimes bleeding – edge of trying to implement change. For example, I don’t think any other state has set a target of 40 percent renewables as early as 2030.”

Public Face of Change

Of course, careful planning and resourceful operations are essential to the company meeting its clean-energy goals. But they’re not sufficient. The ambitions enshrined in the HCEI will require a partnership between the utility and the community. It means going out and engaging the public. It means accounting for people’s skepticism and managing their expectations. And it means focusing on customers and service as much as technology and policy.

In some ways, this perspective is built into all parts of the Clean Energy Team. Operations and planners, for example, are already obsessed with reliability and customer service programs. But the team also includes members whose principal focus is how the company’s clean-energy plans impact public and customer relations.

A Top 250 Leader

Hawaiian Electric Industries – parent company of the electric utilities HECO, MECO and HELCO, and American Savings Bank – has been in the first, second or third spot on the Top 250 since 1990. In the 1980s, the parent company always ranked fourth or fifth.

Photo: Rae Huo

Lynne Unemori

Age: 50

Title: Vice President, Corporate Relations

Clean-Energy Responsibilities: Communicate the company’s green objectives, to both employees and the public.

Unemori points out that there’s both an internal and external aspect to communicating the company’s clean energy goals. Internally, she says, it’s important that employees realize these goals aren’t just window dressing; they represent the utility’s future. “It’s critical to make sure they understand our mission, our vision of what the goals are, how we’re going to stay focused. Most important: making it clear that every employee has a role to play in our future.” Unemori also acknowledges that the company has to communicate that same sense of conviction and commitment to a skeptical public.

That public – the ratepayers and taxpayers who will ultimately underwrite the goals of the HCEI – has to know they have a stake in the process. “Another key message,” Unemori says, “One, I think isn’t always easy – is that we have to make investments in order to harvest this energy, to get the infrastructure in place, to be able to reliably include renewables. This investment will come with a price tag, too. But, if you look at it in a bigger context, it makes a lot of sense.”

Photo: Rae Huo

Dave Waller

Age: 61

Title: Vice President, Customer Service

Clean-Energy Responsibilities: Ensure that the company’s clean-energy programs, like demand-side management or net metering, operate seamlessly for customers.

Waller, who had an earlier career in the petroleum industry, brings a unique perspective to the team. Ultimately, he says, clean energy, like anything else the company does, has to benefit the customer. “Really, to affect all the change that we’re looking for, the customer plays a very important role in that process. What we really want to do is make sure that, in every product, every service, every interaction with the customer, we execute that with clean energy in mind.”

Although it’s tempting to envision the work of the Clean Energy Team in a technological or regulatory framework, Waller notes, “The effects and the work of clean energy really don’t happen until they happen in the customer’s place of business or at the customer’s home.”

Regulatory Dance

In large measure, the future of the utility is in the hands of the Public Utilities Commission. Its shape will be decided through an unprecedented welter of dockets before the commission. The most important – the feed-in tariff and decoupling – which the commission has already agreed to in principle, represent revolutionary changes in the way the company does business. The feed-in tariff will encourage the development of ever more renewable power by establishing in advance the price the utility will pay independent producers. Decoupling removes the perverse incentive to sell more, not less power. It does this by decoupling the company’s income from sales; instead, the company will be rewarded for encouraging conservation and adopting more renewable-energy sources.

Of course, that’s the theory. But figuring out the details of these regulatory changes is the primary responsibility of a couple of members of the Clean Energy Team. In fact, the regulatory framework is so important that almost every member of the team has participated in planning and negotiating the PUC’s final ruling.

Photo: Rae Huo

Darcy Endo-Omoto

Age: 46

Title: Vice President, Government and Community Affairs

Clean-Energy Responsibilities: Work with the Public Utilities Commission and Hawaii’s consumer advocate to develop a sound, clean-energy regulatory structure.

As a regulated utility, none of HECO’s ambitious plans can happen without the approval of the PUC. That’s the bailiwick of Endo-Omoto. “When you put the whole puzzle together, I have the regulatory part,” she says. “I’m also responsible for government relations, which is the liaison between us and the Legislature, the (state) administration, the City Council and the federal side. Also under my area: We do all community relations – neighborhood boards, etc.”

“I think we have to take these aggressive steps, not only because of what state law requires of us in terms of our renewable portfolio standards, but also because of what I can see happening on a national level with respect to climate change and global warming.”

Photo: Rae Huo

Tayne Sekimura

Age: 48

Title: Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer

Clean-Energy Responsibilities: Ensure that clean-energy plans, especially decoupling and feed-in tariffs, leave the company on a sound financial footing.

For regulated industries like HECO, it’s sometimes easy to forget they’re publicly traded companies that still have to make a profit for their investors. As CFO, Sekimura’s role on the team is largely to ensure that, in the rush to meet the company’s clean-energy goals, they don’t lose sight of those basic corporate responsibilities. “I’ve still got to be able to recover costs,” she says. “I can’t give away the candy store.”

The clean-energy agreement inevitably will mean new structures, new financial models for the company. But, as Sekimura notes, they still have to make economic sense. “It’s my job, as financial steward of this company, to make sure, when we go down these paths, that it’s not devastating from a financial standpoint,” she says. It’s a perspective that colors how she negotiates issues like decoupling and feed-in tariffs. “These are not just financial instruments for the sake of increasing profits,” she says. “They’re really the underpinnings of a financially healthy utility that’s able to do these new things and, at the same time, be a supplier of reliable electric power.”