Tracing a Virus

This summer was a blur for Sarah Park, who is the state epidemiologist and head of the Department of Health’s Disease Outbreak Control Division.

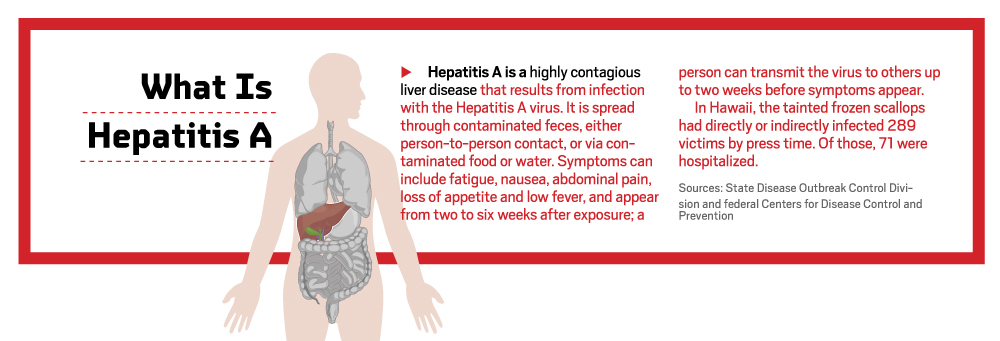

Each year, an average of 10 Hawaii residents contract Hepatitis A, which is considered a normal rate for the size of the state’s population. But, by the middle of June, the Health Department knew this was no ordinary year.

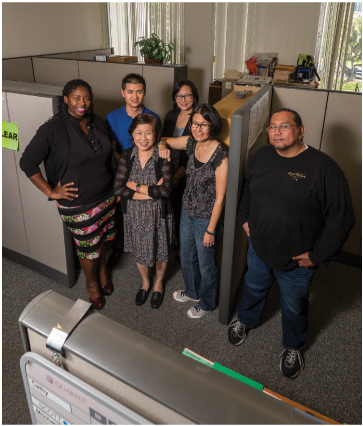

Dr. Sarah Park is the state epidemiologist and head of the team at the Disease Outbreak Control Division that found the source of this summer’s Hepatitis A outbreak. Photo by Aaron K. Yoshino

“Our system identified one case, but we also identified three others, all in the space of a couple of weeks,” she says. “When we heard about two cases, three cases, four cases, all within a couple of weeks – those to us were alarm bells. That’s when we were, like, ‘shit.’”

Her department went into overdrive and could not let up as the cases reached in the hundreds and public pressure mounted. Here’s how Park and her team of 75 people, with help from federal agencies, traced the source of the outbreak. In the world of food-borne diseases, it was an incredible feat, Park says. That’s because Hepatitis A’s long incubation period of 15 to 50 days means the likelihood “of finding a source, or the reason this person got sick, is almost nil.”

June: Ramping Up the Investigation

June: Ramping Up the Investigation

Cathy Wu spends much of her workday on the phone at her desk inside the Health Department’s outdated offices at the corner of Punchbowl and Beretania streets. Wu is an epidemiological specialist with the immunization branch, which oversees vaccine-preventable diseases, including influenza, chicken pox, measles and Hepatitis A. She’s a graduate of the public health program at UH Manoa and has been on the job for more than a decade. This summer’s outbreak was one of the biggest and longest investigations she’s been on, and she was involved from the beginning.

Wu says she and her colleagues, a team of four investigators and a supervisor, are first notified of a new infection case by the department’s electronic laboratory reporting system. She verifies if it’s a true case – whether it’s Hepatitis A or measles – by calling the diagnostic lab to get the test results and then finds the doctor who ordered the test. Wu then makes herself comfortable; she’s in for long phone conversations. During the two-month Hepatitis A investigation, Wu diligently went through a 15-page questionnaire with each of the 45 Hepatitis A cases assigned to her. Her sleuthing had a singular purpose: to collect data in hopes of finding commonalities among her cases to help determine the origin of the outbreak.

She asked each person detailed questions about her or his symptoms, medical history, demographics, activities and travel starting 50 days before the onset of symptoms. Perhaps most important, was collecting a food and drink history starting 50 days before the illness. Wu also contacted each patient’s household members, encouraging them to get vaccinated to minimize secondary exposure. (That part seemed to have worked well: Hepatitis A can also be transmitted from person to person through bodily fluids, but Park says fewer than 10 cases were the result of secondary exposure.) For the cases of people who work in the food industry, Wu says, she needed proof of a negative blood test for Hepatitis A before they could return to work.

“Most of the people were helpful and cooperated. Some were really frustrated, though,” says Wu. “Remember, they were sick, so they didn’t want to talk. I’d have to call them back, or leave them messages. I had one case where she wouldn’t return my calls until one week later.”

Here is part of the team at the state’s Disease Outbreak Control Division that tracked the Hepatitis A virus. From left are Augustina Manuzak, supervisor with the Epidemiology Surveillance Section; Cathy Wu, epidemiological specialist with the Immunization Branch; epidemiologist Dave Johnston; and Ron Balajadia, chief of the Immunization Branch. Photography by Aaron K. Yoshino

If she was lucky, she got through the entire questionnaire in one go, which usually took 45 to 90 minutes. It probably helps that Wu is a patient, congenial woman, and laughs often.

Per case, Wu says, she made at least three calls. At the most, she made a dozen phone calls to track down the patient, plus her or his doctor, employer and family contacts. “It was a heavy load.”

The food history section of the questionnaire was the most meticulous. For example, says Wu, “We’d ask them if they ate bell peppers, but (specifically) green peppers, yellow peppers, red peppers and orange peppers.”

Investigators didn’t rely solely on the fuzzy memories of sick patients, though. To fill gaps in cases’ food and drink histories, they coordinated with grocers and big-box stores. The health officials provided store managers with patient names to get a list of food and drinks each person purchased in the past 50 days before becoming ill. For example, the data collected using loyalty and shopper card programs was invaluable in supplying that information.

But as much data as Wu and her colleagues amassed, by the end of June, 12 people had contracted Hepatitis A and no single food item or place emerged as the likely tainted source.

The cases were scattered across Oahu. “Now that we know it’s Genki, it makes sense,” says Park. “Their 10 stores are all over Oahu, and the fact that we had a couple of cases associated with Kauai – they have one store on Kauai.” But, at the time, the source was still a mystery.

July: The Case Heats Up

July: The Case Heats Up

After the Fourth of July weekend, the number of confirmed infected people climbed to 31. Analysts in the Disease Outbreak Control Division diligently worked to scrub the raw data collected by Wu and other investigators, inputting it into a computer analysis program that spotted patterns.

Chelsea Nichols, foodborne disease surveillance and response coordinator, says the files on the Hepatitis A cases filled over 10 banker boxes. Photography by Aaron K. Yoshino

Park says there were a lot of leads that ultimately fizzled. Immediately, the department spotted a high response for seafood among patients; after all, Hawaii loves raw fish. Park says her team investigated sources of ahi poke at grocery stores and certain restaurants, especially given the product’s link to local salmonella outbreaks in 2007 and 2009. But it wasn’t poke.

Park says the department also considered frozen berries – the source of earlier Mainland outbreaks of Hepatitis A – and investigated packaged meats, shave ice, and even water sources at drinking fountains and the Wet ’n’ Wild Hawaii water park. The department scrutinized every grocery and big box store on Oahu.

When investigators found something of interest, the department’s sanitation branch got involved. Inspectors called or sometimes visited businesses to get their records to see which distributors they used and which products they bought. “We looked at distribution records, lot numbers, dates when things were distributed and tried to match them up with dates of cases and make estimates of when (patients) would have potentially been exposed,” says Park.

However, food distribution records are notoriously inconsistent, says Chelsea Nichols, foodborne disease surveillance and response coordinator. Nichols, who is relatively new to the department and Oahu – this was her first big investigation with the department – says this spottiness is common throughout America’s food industry. “It’s not that (businesses) aren’t cooperative, it’s just how the record keeping is,” she says. “From a day-to-day perspective, they may not see how (records are) useful. Most of the time they don’t need to provide records.” Inspectors spent a lot of time trying to decipher records, sometimes handwritten, and fill in missing information.

Cathy Wu, epidemiological specialist with the Immunization Branch, went through a 15-page questionnaire with each of the 45 Hepatitis A cases assigned to her. Photo by Aaron K. Yoshino

A specific food or drink was crossed off the source suspect list once inspectors verified that distributors provided that same item, poke for example, to restaurants not mentioned by any of the infected people. Park says it’s an exhausting process that required a lot of overtime. “Every time we hoped, ‘Maybe this is it, maybe it’ll narrow it down,’ it would just explode into something bigger.”

But by mid-July, the data started revealing a pattern. Park says infected kamaaina began more regularly naming one business: “Genki started popping up more,” she says.

But other places were still being mentioned, too, she adds. Investigators needed more proof.

August: Confirming the Source

August: Confirming the Source

By early August, after roughly 45 days and 160 infected patients, “Genki certainly was becoming interesting,” says Park. But investigators needed to be sure it wasn’t another dead end, so the team called upon the community.

Here are members of the Immunization Branch, within the state’s Disease Outbreak Control Division, that helped cracked the Hepatitis A case. From left, epidemiological specialists Mariannah Kitandwe and Michael Schweikert; Augustina Manuzak, supervisor in the Epidemiology Surveillance Section; epidemiological specialist Cathy Wu; Heather Winfield-Smith, program specialist in the Vaccine Supply and Distribution Section; and Ron Balajadia, chief of the Immunization Branch. Photography by Aaron K. Yoshino

From Aug. 10 to Aug. 16, the department ran a questionnaire on the website Survey Monkey, asking participants about their food and drink histories over the past 50 days. The response was staggering: Nearly 6,000 people participated.

“It was a nice feeling for all of us, to realize the community was behind us,” she says. “I think it was a way to get the community involved in helping us solve this.”

Park says the Disease Outbreak Control Division compared the responses of the participants to the food and drink histories of the Hepatitis A patients. The survey yielded an interesting anomaly: While less than 25 percent of the survey respondents reported eating at Genki, roughly 70 percent of the Hepatitis A patients did. “The survey clinched our hunch about Genki,” says Park, adding that the data also gave them the confidence to drop other leads.

Once the team was certain of “where,” they needed to solve “what.” Park says she called the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta for extra help. Donnica Smalls, a spokesperson for the CDC, says the center provided epidemiology and infectious disease experts, as well as laboratory support. Three officials were on Oahu for 15 days from early August.

Investigators turned to their deluge of data to eliminate possible food sources. Genki is a conveyor-belt sushi chain that has more than 100 items on its dine-in menus, not including desserts and drinks.

“People were saying, ‘I ate everything on the menu,’ or ‘I ate at Genki, but I’m not sure what I ate,’ ” says Park. “Some said scallops, but some said scallops and tuna and this and that.”

Armed with the where, however, it didn’t take long to identify the frozen scallops as the tainted what. “Once we started narrowing in on the scallops, we were confident quickly that’s what it was,” says Nichols. She says Disease Outbreak Control Division officials partnered with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to wind through the complex maze of food distribution to identify the local supplier of the scallops, the mollusk’s Washington importer and the producer in the Philippines.

On Aug. 15, two months after the investigation began, the Health Department announced raw scallops from Genki Sushi as the likely source of Oahu’s Hepatitis A outbreak. Reaction was swift: Genki closed its Oahu and Kauai locations for three weeks and Sea Port Products, based in Washington state, recalled 800 cases, at 30 pounds each, of frozen raw bay scallops. The FDA positively tested for the Hepatitis A virus in two scallop samples sent to its labs.

By mid-October, the Disease Outbreak Control Division was operating again as normal, but still on the lookout for the next big one. “The whole goal of what we do in public health is to make these nonissues. We don’t want to have an outbreak,” Park says. She says the outbreak is a good reminder for the community to understand that raw food, while enjoyable, comes with uncertainties.

“You still need to live your life and have an adventure, but it’s important for people to understand there’s that risk.”

ZEROING IN ON ZIKA

Hawaii Biotech is working on a vaccine to protect against Zika. Here, Dr. Jaime Horton and vaccine research director David Clements study bacterial colonies on a petri plate. Photography by Aaron K. Yoshino

There’s been a vaccine for the hardy Hepatitis A virus in the U.S. since 1995. That’s why rates for the liver disease are the lowest they’ve been in 40 years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But there’s no vaccine for Zika, a virus that has already reached South Florida. Is Hawaii prepared for Zika? No, says David Clements.

Clements is the vaccine research director at Hawaii Biotech, a vaccine and antitoxin development company. Zika is a virus spread by the aggressive aedes aegypti mosquito, which bites throughout the day, and sometimes at night. The most common symptoms of the virus are fever, rash, joint pain and red eyes. But the virus can also be passed through sex, and from a pregnant woman to her fetus, potentially causing serious brain defects.

That’s why this March, Hawaii Biotech began work to develop a vaccine for Zika. The company, founded in 1982, is currently self-funding its Zika vaccine research, says Clements. It also has a West Nile virus vaccination program in progress, and began research to develop a vaccine for chikungunya in August. Like Zika, both viruses are also mosquito borne.

“Hawaii Biotech’s first vaccine was for dengue fever in the 1990s,” says Clements, adding that Merck & Co. later purchased the vaccine research. “This class of viruses is related to dengue. We can apply some of the basic technologies.”

This year, Zika has made headlines virtually every week, in part due to the summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where the virus is rampant. U.S. health officials have scrambled to study the virus – including trying to determine its full effects on fetuses and how the virus is transmitted – especially since the disease reached Florida. But Zika isn’t new, Clements says. Zika and dengue have existed since the mid-1940s, and chikungunya since the early 1950s, but we’re seeing a resurgence of these viruses because of urbanization and global travel.

“We are a global village in so many ways,” adds Sarah Park, the state epidemiologist. “I use that term in relation to infectious diseases, too. You can hop a plane from one side of the world to another. Physicians should always ask a travel history as part of an exam now.”

The vector of the disease, aedes aegypti mosquitoes, are dubbed “the cockroaches of mosquitoes,” says Clements, because they’re mainly urban dwellers and difficult to eliminate. “Wherever man is, aedes aegypti is. The more densely populated urban environments, plus the virus, equal the perfect storm.”

David Clements, vaccine research director at Hawaii Biotech, retrieves insect cells from liquid nitrogen storage. A smiliar secure container stores Zika virus for research. Photography by Aaron K. Yoshino

So why is Zika spreading across Central and South America and the Caribbean – Puerto Rico is considered “ground zero” for Zika – but not the U.S.? Clements speculates that the region’s tropical climates and dense metropolises make ideal homes for the mosquitoes, but there are few resources to fight the ensuing viruses.

“The U.S. hasn’t really been impacted. In part, it is the developing world versus the developed world,” says Clements. “Is that absolute? No one knows, but it’s a factor.”

To develop vaccines, Clements says, Hawaii Biotech works with proteins from outside the virus, rather than the live virus. He says the company hopes to begin the first human clinical trials for a Zika vaccine next spring. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration must review three clinical trials before approving a vaccine.

Hawaii Biotech receives roughly $6 million annually in funding from government grants and contracts; since its founding, it has been awarded more than $50 million. Bringing a vaccine to market requires serious funding. Clements says it can take anywhere from five to 15 years from research to licensed product and costs can skyrocket from $100 million to $500 million.

Clements says firms like Hawaii Biotech are pursuing vaccination research, despite the country’s current low infection numbers and the extended time it took Congress to pass $1.1 billion in funding to combat Zika. “These are vaccines worth developing,” he says. “The only way to ensure that people are protected is through vaccination.”

ZIKA IN THE U.S.

Zika cases in America from Jan. 1, 2015 through Oct. 12, 2016:

- 3,807: Cases of people who contracted the virus while outside of the U.S. before entering or re-entering America

- 128: Locally transmitted cases in the U.S., all in Florida

- 14: Travel-associated cases in Hawaii

- 25,871: Locally transmitted cases in three U.S. territories: Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands and American Samoa, with 98 percent in Puerto Rico.