Toxic Waste in Hawaii

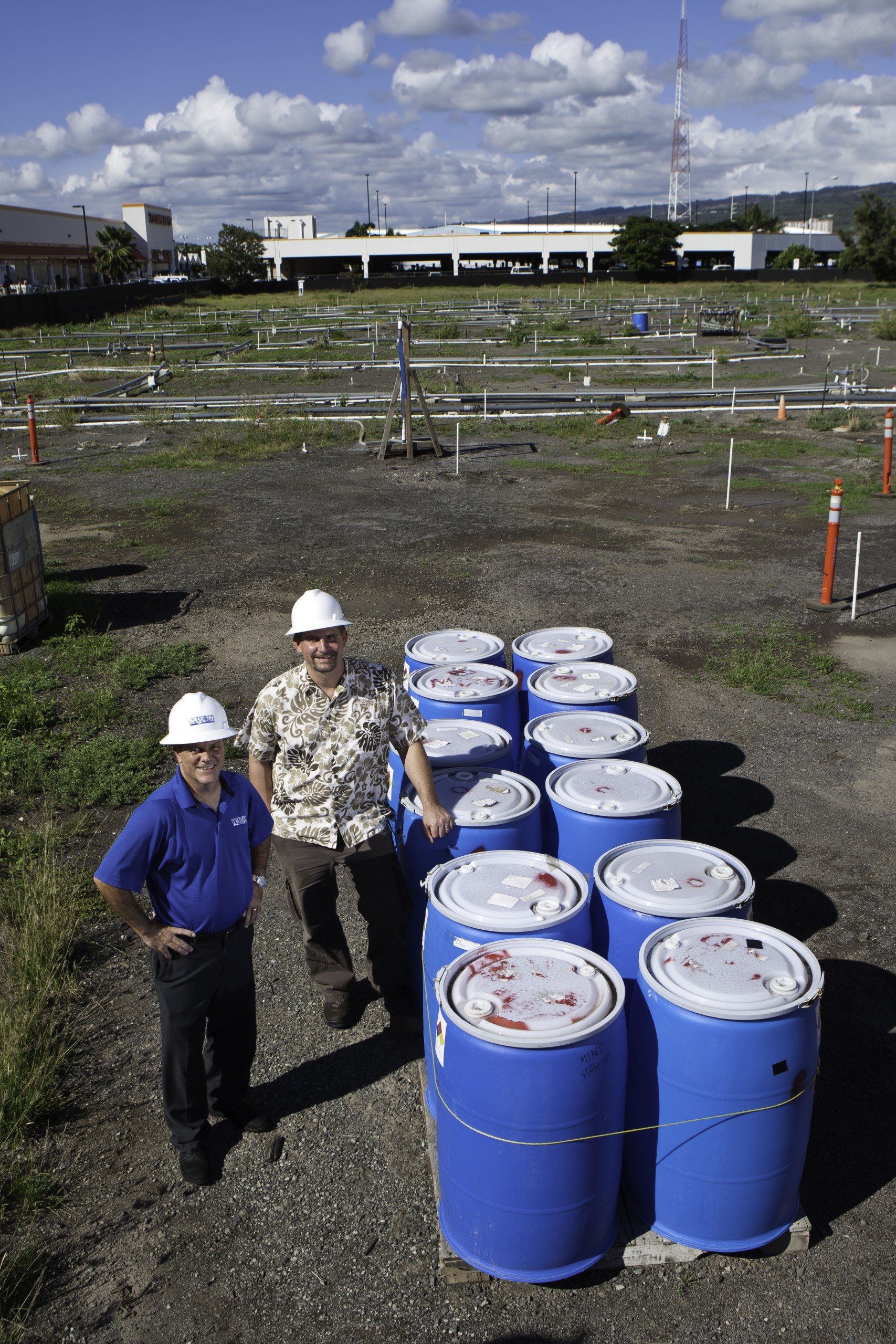

Opeartings manager Dave Griffin, left, and Mark Amber are confident that Weston Solution’s chemical oxidation process can clean up the old GasCo site in Iwilei. The contaminate property is immediately makai of the Home Depot store.

Thirty years after it shut down, the old Gasco site in Iwilei is still a vacant lot. For generations, it converted heavy petroleum into synthetic gas and light oils. Now, its storage tanks, thermal cracker unit and pipelines are long gone and, in their place, is a field of gravel and weeds.

All that remains of the old gasworks is its contamination – a vast underground reservoir of viscous tar and toxic aromatics, like benzene, toluene and ethylbenzene. Indeed, the Gasco site is one of the most contaminated sites in the state, and the technical and legal consequences of that contamination are why the land sat vacant for more than three decades. Even so, three years ago, Weston Solutions, an international environmental engineering company, bought the property – and all the liability that goes with it.

That’s because the four-acre site is prime real estate. It’s near downtown, the harbor, airport, highways and the planned rail line. Weston plans to clean it and redevelop it, but three years after buying the land, Weston’s project still faces technical glitches and regulatory hurdles, and has become a symbol of Hawaii’s contaminated lands problem.

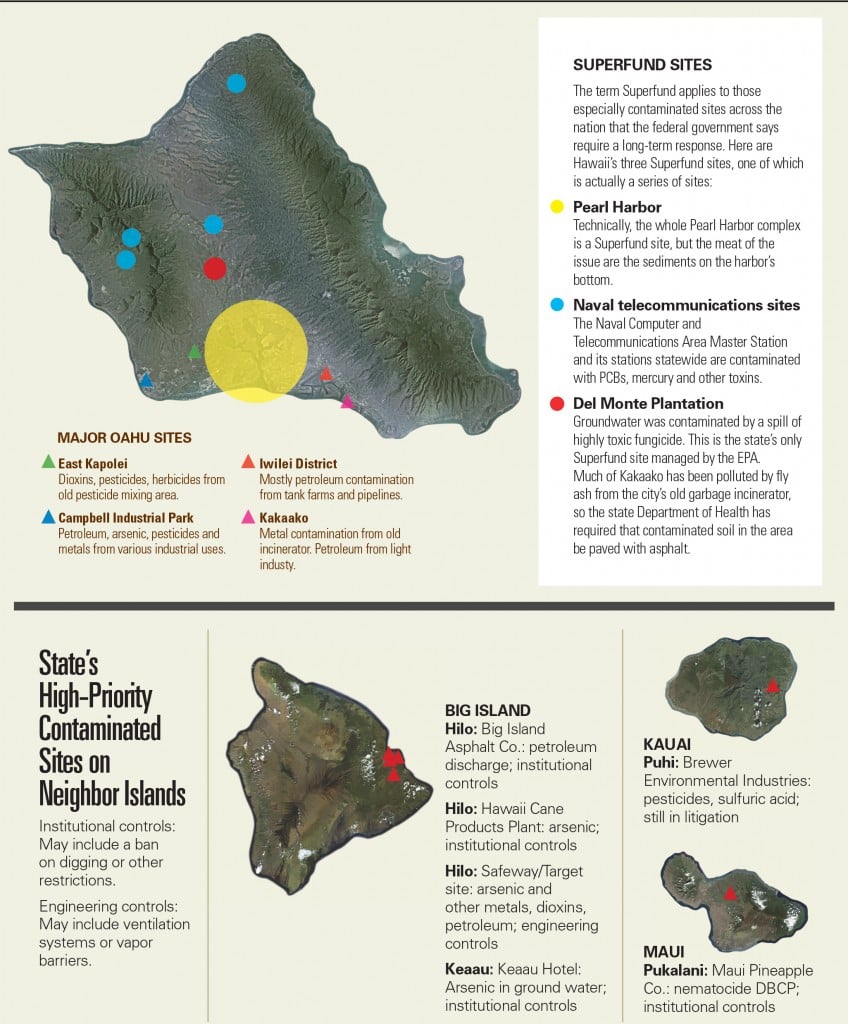

Distribution of toxic sites

Here’s the good news: Hawaii is much less affected by contaminated sites than most Mainland states, according to Fenix Grange, manager of Site Discovery, Assessment and Remediation for the state Department of Health. That’s largely because we haven’t had as many heavy industries as in the Rust Belt or the petrochemical regions of the Gulf Coast. Also, according to Grange, it’s rare for contaminated properties here to sit idle.

“In Hawaii, because land is so valuable, most large, urban properties that have contamination on them get developed anyway,” she says. “People just make the cleanup and control costs part of their redevelopment plans,” Grange says.

Nevertheless, industrial areas like Iwilei, Campbell Industrial Park, Mapunapuna and Kakaako are heavily contaminated, which complicates land sales and development. The main issue, of course, is liability for the required cleanup, which can mean millions of dollars in uncertain expenses.

Beyond these large, well-known industrial sites, there are hundreds of anonymous, smaller sites: dumps, auto-repair shops and old underground tanks at gas stations. Former sugar and pineapple plantations have dozens of contaminated sites that were once used for fertilizer storage or pesticide mixing.

The state Department of Health has investigated more than 1,700 sites of potential contamination, nearly half of which merited further action. “We have about 800 sites in our database that have current or historic contamination that are either still dirty, or were dirty and have been cleaned up,” Grange says.

Joint and several liability

Hawaii’s rules on toxic sites are mostly derived from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s regulations. “In federal law,” Grange says, “liability is ‘joint and several,’ which means anybody associated with the contamination is in the chain of responsibility. The regulators look first to the party that actually caused the contamination. Then they look to the current property owner. But anyone associated with the contamination is in the chain of responsibility.” That means, the current property owner is on the hook, but so is the previous owner.

An excellent example is Weston’s other Oahu project, the old Chem-Wood facility in Campbell Industrial Park. From 1973 to 1988, Chem-Wood, a Campbell Estate tenant, used copper chromate arsenic to pressure-treat lumber there. Campbell sold the property to Chem-Wood in 1989, but, under duress from the EPA to clean up the site, Chem-Wood went bankrupt in 1997, leaving behind tanks of the toxic chemical. In 2008, vandals broke in, spilling 300 pounds of the copper chromate arsenic. Arsenic levels in the soil are now some of the highest in the state.

In the intervening years, other responsible parties have disappeared. The most recent owner, a Japanese businessman who also faced pressure to clean up, walked away from the property, taking haven from the EPA in Japan. His predecessors went bankrupt. But bankruptcy is not an option for the Campbell Estate; its pockets are too deep. Until it sold the site to Weston Solutions, it was stuck with all the liability for the cleanup, even though it hadn’t been the owner of the property for more than 20 years. That’s the principle of “joint and several.”

The uncertainty and risk created by joint and several liability has made it difficult to redevelop parcels that are contaminated – or are even suspected of contamination. As a result, the EPA and state regulators have devised programs intended to ease liability for buyers that want to redevelop a contaminated property. The state’s Voluntary Response Program, for example, provides owners and purchasers with technical assistance, quicker oversight and some relief from future liability.

“With the VRP,” Grange says, “a developer comes in, agrees to characterize a site and take responsibility for the contamination up to a level suitable for their proposed use, and then they’re free from additional liability.” She adds that the liability for the remaining contamination doesn’t simply go away. “That liability stays with whoever caused the contamination in the first place.”

She gives an example from Iwilei: “The site of the Lowe’s store has a bunch of petroleum-contaminated soil from the old ConocoPhillips tank farm. Lowe’s wanted to build its store there, but it didn’t want to assume all of ConocoPhillips’ responsibility. So it entered our VRP and agreed to remediate within the property boundaries to a level that was safe and appropriate to build a commercial store. The VRP leaves the remaining environmental responsibility with ConocoPhillips.”

Probably the most important program for encouraging the redevelopment of contaminated lands has been the federal Brownfields Program. This law, which was mirrored at the state level in 2009, provides many of the same protections as the VRP. “We have about 20 VRP sites in the state,” Grange says. “But with the new Brownfield purchaser law, I think there will be less need for those in the future, because they can get those protections automatically now.”

One of the big differences with the Brownfield Program is its funding options. “Right now, we have what’s being presented as the poster child for Brownfield,” says Mike Yee, one of the principals at the local consulting firm EnviroServices and Training Center. “That’s our East Kapolei site, the pesticide-mixing site and surrounding area in Ewa that the Department of Hawaiian Homelands wants to put homes on.” Through the Brownfield Program, DHHL is funding some of its environmental assessment costs with a $200,000 EPA grant. DHHL is also the first entity to use a $1 million EPA revolving fund administered by the state Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism. This money can be used for the actual cleanup and paid back after the property has been redeveloped.

“Wow,” says Yee. “What a wonderful way to use federal money: to bring that money into our state to investigate and clean up contaminated sites. It’s good for the developer, good for the state and, ultimately, good for the community – not to mention the environment.”

Weston has created an interesting business model for its Gasco and Chem-Wood projects. Typically, environmental firms are simply consultants or subcontractors; the developer remains liable for the contamination. But Weston bought these properties outright. In effect, Weston has gambled on its expertise in environmental engineering, believing it can purchase properties at a discount, clean them and sell them at a premium. In the interim, though, Weston is the responsible party as far as DOH is concerned. In the lingo of environmental engineers, Weston has bought the liability.

“I’d like to tell you that we’re really smart at this,” says Dave Griffin, Hawaii Operations Manager, “but we have a card up our sleeve: We buy an insurance policy. We engage insurance to underwrite this risk for us, so if we encounter 50 drums of methyl-ethyl that nobody knew about, we can recover some of our expenditures.”

While being the property owner is much riskier, Griffin points out some advantages. To begin with, any upside on the development end of the deal belongs to Weston. And since the company’s cleanup agreement with DOH is based upon the end use for the property, Weston can tailor its cleanup process to a specific function, potentially saving money.

There’s also the method of payment. Although Weston technically “bought” the property from BHP, the details of the contract are more complicated: The seller pays most of the downstream costs. “Instead of billing for hours,” Griffin says, “we get paid up front. So now we’re sitting on that money, drawing interest. Financially, that makes a lot of sense.”

Rick Smith elaborates: “You get paid for everything up front,” he says. “So they (property sellers) pay for the insurance. We don’t pay for that. … The cost of the cleanup, what we actually do in the field, all that’s paid up front. All that’s part of the calculation.” But he notes there’s a lot of prelude before the symphony of cash. “That reward, that big lump of money, doesn’t just stroll in the front door. There’s a lot of work that goes into putting one of these deals together.” In this case, the deal took 18 months to arrange.

“It’s not for the faint of heart,” says Griffin. “The truth is, we’re trying to do the right thing here. By redeveloping this property, we get jobs, we get tax base and we get a more vibrant community out of the deal. That’s our kind of model. Would we like to make some money at the end of the deal? Absolutely. We found a piece of property that’s been sitting vacant for 30 years (the old Gasco site), and it’s right next to the highest-selling Costco in the country. We think we’ve found a little gem here. But, in the end, it’s Weston’s contamination now.”

Bankers and Consultants

Although a large, international company like Weston Solutions can afford to self-finance its projects, most local companies interested in redeveloping contaminated property will need a lender. And that’s just the beginning, says Scott Rodie, environmental risk manager at Bank of Hawaii.

“Banks don’t like uncertainty,” says Rodie. “What we try to do, cooperatively with the client, is help them avail themselves of the experts that are out there.”

That means making sure their clients have qualified environmental consultants and appropriate insurance, and that, overall, they know what they’re getting into.

One problem is figuring out if your advisors are knowledgable. “It’s unregulated and unlicensed,” Rodie says. “Under federal law and Hawaii Revised Statutes, there are requirements that you have an ‘environmental professional,’ as defined by the rule, perform a Phase-1 (site investigation). But, again, it’s unlicensed. You have nearly nothing to go after” if they get it wrong.

“So it’s buyer beware,” Rodie says. Or, better yet, listen to your banker.

How Toxic Land is Cleaned

Environmental engineering companies have several ways of cleaning contaminated land, from the most basic method to high-tech solutions.

First, figuring out if there is anything toxic in the ground, what it is and where, can be complicated. Mike Yee, of EnviroServices, elaborates: “How far down does the contamination go? How wide has it spread? What are the actual contaminants and what is the level of the contamination? Then we look at remediation alternatives – what’s the best way to treat it? Normally, there’s not just one way to clean up a site, and there are a lot of factors that go into determining which one you select.”

One option is very basic: dig up the contaminated soil and remove it. Damon Hamura, project manager for EnviroServices, calls it “Bag it and tag it.” With this method, you’re not actually getting rid of the contaminant; you’re just moving it – often to a landfill.

That’s sometimes the only solution, particularly with metals contamination, but it presents its own problems, including moving truckloads of contaminated soil through the neighborhood.

“Sometimes,” Hamura says, “they just put it back on the same site – a kind of reinterment. They dig a pit, put all the contaminated soil in there, then cover it with concrete or asphalt. That’s called ‘encapsulation.’ ”

This is the strategy being used at the Chem-Wood site in Campbell Industrial Park.

When it comes to cleanup options, Hamura says, “Removal is a pretty short list, but when you get to remedial action, it’s a relatively long list. And it’s getting longer as technology grows.” This is particularly true for petroleum-based contaminants, the prevalent form of soil and groundwater pollution in Hawaii. For example, you have various kinds of bioremediation – basically using petroleum-eating microbes, either natural or introduced – to remove the contaminant. This is often combined with sparging, essentially bubbling oxygen through the groundwater to improve the effectiveness of the bacteria.

A more radical approach is thermal desorption. “Basically,” Hamura says, “you’re heating up the soil, trying to burn off the contaminants. But you also need to capture the vapor that’s produced. Usually, you use this method for organic contaminants. If you have a metals issue, that’s not going to do much for you.”

Often, remediation is an ongoing responsibility. Many properties, especially those that have passed through the VRP or Brownfield Program, require “administrative controls.” These controls might forbid digging or strictly limit the use of the property.

The remediation can also be engineered into the new development. In areas with petroleum contamination, like the Lowe’s and Costco sites in Iwilei, this probably involves the installation of a vapor barrier and a vapor extraction system.

Weston plans a more aggressive approach with the tar and benzene at the Gasco site. “We’re proposing to use in situ chemical oxidation,” says David Griffin, Weston’s operations manager in Hawaii. “That’s pumping 40,000 gallons of diluted industrial-grade hydrogen peroxide into the ground. That treats the contamination. (The byproducts are carbon dioxide and water.) Plus, it destroys the contaminants in place, so we’re not bringing them to the surface, putting them in trucks and hauling them through the local neighborhoods.” This drives the benzene out of the groundwater to a ventilation system on the surface, where it’s burned off. “Then, we do a monitoring program to make sure we’re meeting the levels we signed up for,” Griffin says.

This system is not without risks. Last September, the flame arrester failed on the thermal oxidizer – basically a big furnace – and the resulting backflash caused an explosion in the PVC ventilation system, which ignited a small fire in a benzene vent. No one was hurt, but the fire department arrived in HazMat gear and took two hours and 200,000 gallons of water to put out the tiny fire. Nevertheless, Weston is confident in its system – early tests suggest it’s already lowered the benzene level 60 percent – and only awaits Department of Health approval to expand from the current test grid to the whole site.