Top-Flight Leadership

Mark Dunkerley turned Hawaiian Airlines into a world-class carrier

“You’d have to be crazy to get into the airline business,” Mark Dunkerley said wryly.

The Hawaiian Airlines CEO was speaking late last year to a group of young leaders from the Pacific Century Fellows, trying to summarize the keys to success in the topsy-turvy airline business. His analysis, only partly tongue-in-cheek, could be summarized in a word: Bankruptcy.

“What’s bizarre in this industry,” he said, “is that the better you do as a business, the less competitive you become.” Success inevitably breeds higher costs for an airline – more money for fuel, equipment, maintenance and labor. For an airline, most of those increases are irreversible, spiraling gradually out of control. Dunkerley, who began his career trying to turn around troubled divisions at British Airways, and has since had his fingers in every nook of the industry, from ground services to pilots, knows this dilemma as well as anyone.

“There’s really only one way to blow up your cost space,” he told the group of young leaders, with just a trace of irony in his voice. “That’s by going to bankruptcy court. And airlines have always been serial visitors to bankruptcy court. Aside from Alaska Airlines, I think every other U.S. airline has been to bankruptcy court at least once. Most have been there several times.”

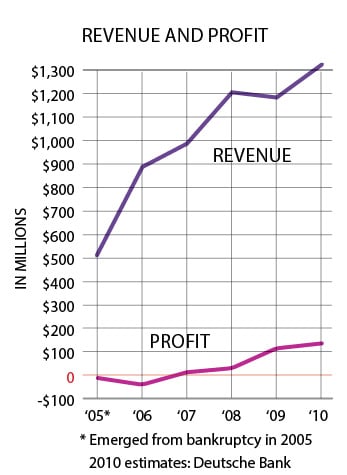

The real irony, of course, is that, since bringing in Dunkerley, in 2003, to guide the company through its own bankruptcy, Hawaiian has become one of the world’s most profitable airlines, even as the rest of the industry has struggled. That’s a matter of tremendous pride to Dunkerley and a key reason we have named him 2010 Hawaii Business CEO of the Year.

“In terms of the financial strength of airlines,” he says, “two years ago, we were rated No. 11 in the world, and the top-rated U.S. airline. Last year, we were the sixth most financially successful airline on the planet, behind the likes of Singapore Airlines and some of the marquee names in the industry, and ahead of much, much better known airlines, including all the major U.S. carriers and my alma mater, British Airways.”

To get these kinds of results, you have to understand the challenges. That, of course, was the subtext to Dunkerley’s talk with the Pacific Century Fellows. “You know,” he said recently, “we’re a business where most of our costs and expenses are either fixed for the long term or we have no control over them. That includes the fact that we commit to aircraft for 20 years or more, and that we have collective bargaining agreements that cover roughly 90 percent of our employees. Those are the two huge expense items, and we have little opportunity to influence them in the short term. We have other costs, the biggest of which is fuel, which we have no control over.”

Similarly, Dunkerley says, an airline’s income depends upon events far beyond the industry’s control. “Our revenue base is very volatile,” he says. “It goes up and down according to recessionary cycles. You need only look back over the last five or six years to see there have been at least three huge events that have dramatically affected the revenues of airlines: the recession, 9/11 and SARS. So we’re in a business where you might conclude we’re just along for the ride.” Instead, he says, airlines only succeed where they focus resolutely on the things they actually can control.

“There was a time when you didn’t want to say you worked for Hawaiian Airlines. Now, you’re proud to be part of this company.”

— David Figueira, Hawaiian’s union representative for the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers

All of which highlights the importance of strategic planning in the airline industry. That’s what many outside observers view as Hawaiian’s greatest strength under Dunkerley. “They’re so forward thinking,” says Peter Ho, CEO of Bank of Hawaii, which has been the airline’s bank of record for decades. “Here’s a company that was in bankruptcy, and yet they were thinking about the refleetment of their interisland operations, which they achieved, by the way, with the acquisition of the 717 aircraft. So, now they can expand their network over the western United States.”

That flexibility is now being compounded by the addition of A350s to the fleet to accommodate the airline’s new, long-distance routes, like those to Australia, the Philippines, and now Japan and Korea. “Not everyone has the gumption to do that kind of expansion just two years after the worst recession since the Great Depression,” Ho says.

New routes and better airplanes are just the most dramatic examples of Hawaiian’s strategic planning under Dunkerley. Some of the airline’s success also comes from small, technical changes in operations. Dunkerley uses the example of how a new approach to ticket sales helped raise profitability.

“We were among the very first airlines to fully exploit the online ticket sales opportunity,” he says, noting that means both lower costs and greater control. “When you sell your seats through intermediaries, they’re the ones who get to decide, for example, whether you pay more to travel during a peak period than you do for a trough period. We think we’re better off making those decisions ourselves.” More and more, they are. “Seven years ago,” Dunkerley says, “roughly three-quarters of our tickets were sold through intermediaries. Today, I believe I’m right in saying that we probably have a greater percentage of our tickets sold through our Internet sales than any of the legacy airlines.”

With Dunkerley at the helm, Hawaiian has gone through a host of similar changes. “We’ve sharpened up our act across the spectrum of our operations,” he says. “We became the on-time leader. We’ve cleaned up our airplanes. We’ve introduced a new fleet. We’ve sold our tickets in different ways. We’ve developed a new brand image, which you can only do when you have a direct relationship with your customer. We’ve forged relationships with other carriers. We’ve looked for new markets, and we’ve entered them. When I first got here, there were a bunch of cities on the West Coast that we didn’t fly to, and we didn’t fly to any of the international cities we fly to now: Sydney, Manila, Japan and Korea. By the time this comes to print, we’ll be in Haneda and knocking on the door of Incheon.”

But perhaps the most important change that Dunkerley has brought to Hawaiian has been a new attitude. “In 2003, as the company was about to file for bankruptcy, there was a tangible feeling through the length and breadth of the company that we were inferior to everybody else in the industry. After all, here we were a little airline based in Hawaii, and there were these big marquee names: United, American, Delta, Continental and Northwestern, at the time. ‘Surely,’ people thought, ‘we were always going to play second fiddle to the big airlines that were so much better known.’ ”

Dunkerley and his team didn’t think so. “We had to find a way to galvanize our employees and demonstrate that we shouldn’t play second fiddle to any of these guys. As we looked around for a rallying point, we settled on on-time performance. This is against the backdrop, mind you, of HAL: ‘Hawaiian’s always late.’ There was just an embedded belief that we were incapable of running our operation smoothly and on time. But we put a lot of time and effort and focus into achieving the first-place position in on-time performance.”

“You’ve got to have the nuts and bolts talents – and I think Mark can get into the business as deep as anyone in the industry – but you’ve also got to be able to look at it from the 30,000-foot level and make strategic decisions. Mark does both well.

— Peter Ho, CEO, Bank of Hawaii

The result, of course, is that Hawaiian has been at or near the top of airline industry on-time performance since 2004. More important, Dunkerley says, is that the company-wide commitment to service has led not only to better morale within the company, but to a measurable improvement in Hawaiian Airline’s brand outside the company.

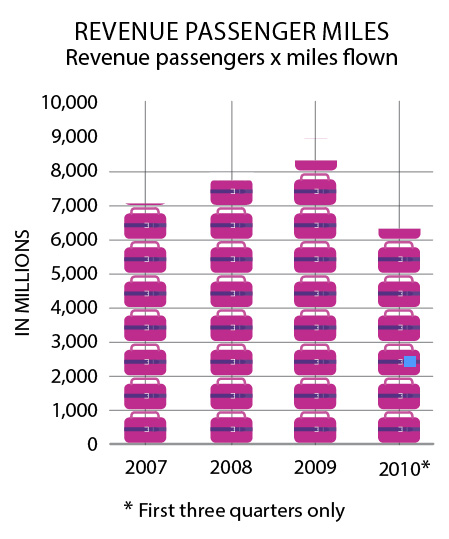

None of this has been lost on industry observers, who are clearly bullish on the company under Dunkerley’s leadership. Analysts like Deutsche Bank’s Michael Linenberg point to revenue growth that could reach 11 percent by the end of this year. Cargo revenue alone experienced an impressive 41 percent jump in the third quarter of 2010 compared to the third quarter of last year. And, most importantly, Linenberg notes, the growth in passenger revenue has steadily improved the company’s margins.

“Perhaps most impressive of the September quarter results,” he writes, “was the company’s solid operating margin of 10.8 percent, which handily exceeded last year’s margin of 8.0 percent and our estimate of 10.2 percent. The company has proven its ability to produce strong results, even as competition heightens in its home market.”

It’s that profitability, according to Dunkerley, that makes everything else possible. Profitability is why the airline has been able to renegotiate relatively generous contracts with its unions. Over the last 10 or 15 years, Dunkerley says, industry wages, in real terms, have fallen 20 percent to 40 percent. Since emerging from bankruptcy, though, Hawaiian’s approach has been to increase productivity rather than decrease wages.

Sharon Soper, president of the American Flight Attendants Hawaiian chapter, points out that union workers have made concessions since the 1980s, “just to keep the airline going to fight another day.” Since Dunkerley and his team took the helm, however, the outlook has improved. “When you look at our contract and our wages and working conditions now,” Soper says, “we’re actually up there at the top of the scale.”

This kind of shared success naturally eases tension between labor and management. David Figueira, Hawaiian’s union representative for the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, says the airline’s expansion and growth has dramatically improved morale, especially among longtime employees. “There was a time when you didn’t want to say you worked for Hawaiian Airlines,” he notes. “Now you’re proud to be part of this company.”

Within the local business community, the reputations of Hawaiian Airlines and Mark Dunkerley have grown in tandem. “I think Mark is a world-class executive,” says Peter Ho. “And it’s important to note that when Mark arrived, he ran a vastly different Hawaiian than the successful airline we see today.” He notes that the kinds of changes Dunkerley has brought to the airline calls for a wide mix of skills. “You’ve got to have the nuts and bolts talents – and I think Mark can get into the business as deep as anyone in the industry – but you’ve also got to be able to look at it from the 30,000-foot level and make strategic decisions. Mark does both well. On top of that, he’s somebody that’s obviously adept at building a team; and he’s got a great team around him.”

It’s the way that team has worked together that means the most to Dunkerley. “What makes me enormously proud,” he says, “is that it was done the old-fashioned way. It was everyone pulling together and looking at every part of our business, making better decisions and grinding it out. There was no Hail Mary pass, no trick play. It was one play at a time. And the most satisfying to me personally was to see how the employees feel about themselves when they recognize that they’re part of the success.”

Even though the airline business is still a harrowing industry – one where bankruptcy is often seen as the ultimate remedy – it doesn’t seem to scare Dunkerley. “We’re in a business where you’ve got to love competing hard and taking calculated risks. If that stuff scares you, you’re probably not in the right business. That said, the challenge for us is we’re going to be building our presence in markets that we haven’t served before. So, we have to execute well. Day-in, day-out, we have to be on our best game. We can’t take it easy. We have to be prepared for some unforeseen thing happening. We’ve got to stay focused.