Timeshare in Hawaii: Build it and They Will Come

It seems like a contradiction: The traditional hotel business in Hawaii is shrinking even while the hospitality industry recovers from the recession, more visitors arrive and they pay more per room than last year.

The relative decline of stand-alone hotels is a trend that has persisted for years and will stretch into the future. Over the past decade, hotel rooms have fallen from 70 percent of the state’s lodging inventory to less than 57 percent, according to a report from the state Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism. Even as Hawaii tourism enjoyed boom times during most of the past 10 years, the overall hotel inventory actually declined by 7,599 rooms.

No stand-alone hotels are being built today while almost every other form of visitor accommodation has grown, including condominium hotels, hostels, vacation rentals and, most importantly, timeshares. As the number of hotel rooms fell over the past decade, timeshare’s share of the overall hospitality inventory doubled.

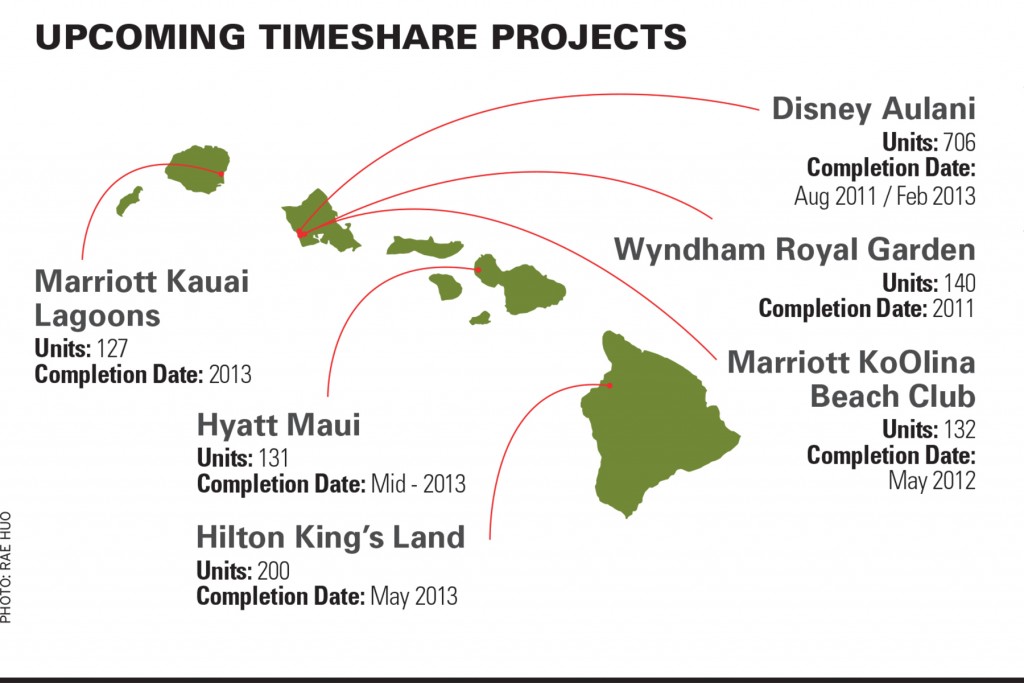

Hawaii now has 87 timeshare resorts and that number keeps growing in a time when no one is building stand-alone hotels. Almost every major hospitality company in Hawaii is developing new timeshare properties, converting existing hotels into timeshare, or rehabilitating the timeshare they have.

Timeshare also has its detractors. Many owners complain about high maintenance fees, or that the flexibility that seemed so straightforward during the sales pitch doesn’t always work out in reality. Even industry executives acknowledge timeshare’s shady past, when the industry was dominated by high-pressure sales and dubious claims about investment potential, but they say much of that bluster is gone and the industry has grown more sophisticated. This change is partly due to the introduction of more consumer protections and better self-policing, but mainly because the industry today is dominated by big corporations like Hilton, Disney, Hyatt, Starwood, Marriott and Wyndham. These are some of the best-known brands in hospitality and they’ve helped bring timeshare into the mainstream in Hawaii.

Prices in Paradise

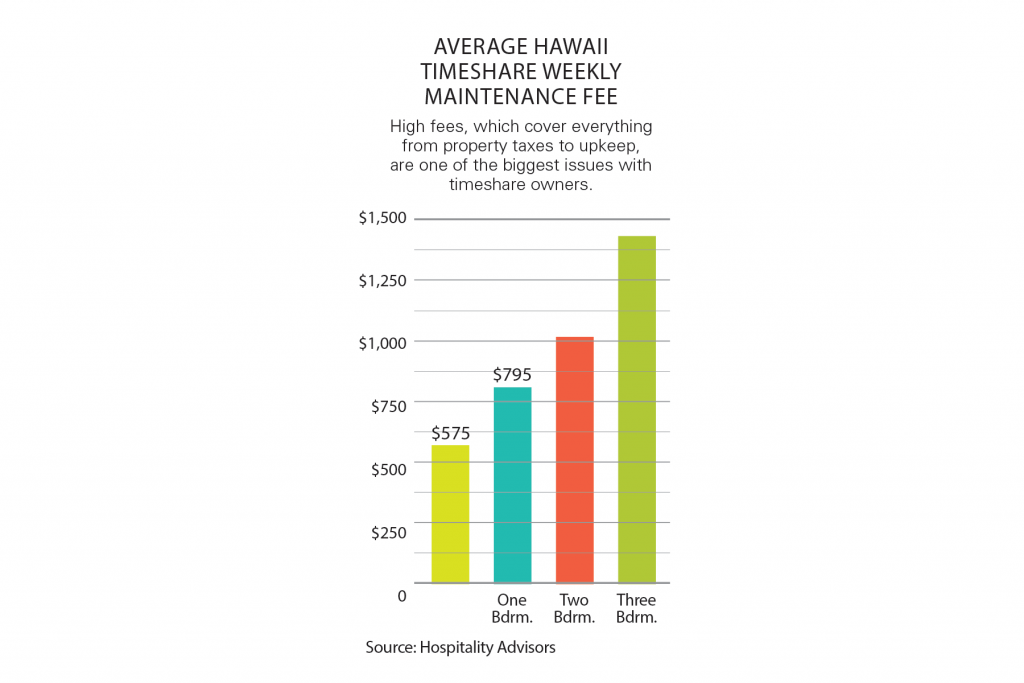

Timeshares aren’t cheap, especially in Hawaii. A typical two-bedroom unit in Waikiki can sell for upwards of $80,000 for a prime week (though the same unit might sell for half that in the resale market). This suggests that a well-appointed, two-bedroom apartment in Waikiki is worth about $4 million, clearly an inflated price. And the cost doesn’t end with the purchase price. Timeshare owners must pay maintenance fees, which cover everything from property and excise taxes to routine maintenance and the condominium’s reserve fund.

Timeshares aren’t cheap, especially in Hawaii. A typical two-bedroom unit in Waikiki can sell for upwards of $80,000 for a prime week (though the same unit might sell for half that in the resale market). This suggests that a well-appointed, two-bedroom apartment in Waikiki is worth about $4 million, clearly an inflated price. And the cost doesn’t end with the purchase price. Timeshare owners must pay maintenance fees, which cover everything from property and excise taxes to routine maintenance and the condominium’s reserve fund.

The maintenance fee for that two-bedroom timeshare in Waikiki will likely set you back upwards of $1,000 annually for each week of ownership. Not surprisingly, these maintenance fees are one of the main objections of potential buyers. Imagine paying condo fees of $52,000 a year.

Nevertheless, the role of timeshare within the hospitality sector is growing. Joe Toy, president of the consulting firm Hospitality Advisors, reports that there are nearly 10,000 timeshare units in Hawaii, or 13 percent of the total lodging inventory. The allure of timeshare is such that nearly 6,000 Hawaii residents own timeshares in Hawaii.

Timeshare’s influence is even more obvious when you start to look at occupancy rates. “In Hawaii, timeshare properties average about 90 percent occupancy,” Toy says. “And that’s down from prior years.” To put that in perspective, Hawaii hotel occupancy in the bitter year of 2009 was about 66 percent. The reason for the difference, of course, is that timeshare owners have prepaid for their lodging and they want to use it. That means their vacation plans are less likely to be thwarted by economic or political upheavals.

“Even after 9/11,” Toy says, “timeshare occupancy was in the 70 percent range, when the rest of the state was around 30 percent.”

This is one reason so many hotel companies have added timeshare to their quiver: When your hotel guests stop coming, you can still count on the timeshare crowd to help fill your restaurants and shop in your stores.

Other numbers reinforce this picture. Toy’s report shows that the average stay for timeshare visitors is nearly a week. They typically travel in larger groups, and they tend to spend more money in the community, nearly $1,600 per party. In other words, these are some of Hawaii’s most reliable and free-spending visitors. They’re also locked in; the state doesn’t have to spend its marketing dollars to find and persuade them to come.

There are other benefits to the overall state economy from timeshare. One is a marketing strategy that liberally uses incentives and gifts to attract people to timeshare sales presentations. “That’s sort of a fundamental part of our marketing,” says Bryan Klum, executive VP of Hilton Grand Vacations. “In exchange for the customer giving up some of their valuable vacation time, we usually provide some sort of gift.” These gifts might be discounts on accommodations, or credits that can be spent at the resort’s restaurants and shops. More frequently, though, the gifts are virtually cash. “We often just give customers Ala Moana gift cards,” Klum says.

Hilton is far from unique. “As an incentive, we offer $125 dining coupons that can be used at several different restaurants in Lahaina,” says Robert Welch, general manager of Marriott’s Maui Ocean Club. “It’s a huge part of our marketing.” All these marketing dollars ultimately end up in the pockets of local vendors rather than in those of out-of-state media and advertising outlets. Large properties in Waikiki, which may give sales presentations to 10,000 to 20,000 customers a year, each contribute millions of dollars annually to the incomes of the shops, restaurants and activities in their neighborhoods.

Then, of course, there are jobs. “There’s a lot of economic benefit from our industry,” says Hilton’s Klum. “There’s the tax revenue that’s raised; there’s the passed-along spending of our customers; there’s the marketing money that we spend, both in state and out of state. But where the rubber really meets the road is the number of people we’re able to employ directly.” Hilton alone, he says, employs more than 700 people in its timeshare operations.

Disney estimates the construction of its Aulani project on Oahu created 1,200 new construction and permanent jobs. According to Hospitality Advisors, the timeshare industry directly contributes more than 4,400 jobs to the Hawaii economy, with a total payroll exceeding $226 million a year. It’s worth noting: That’s an average annual income of nearly $51,000.

Developers’ Incentive

The timeshare industry has been one of the few private sources of economic growth in the state over the past two years. For example, Disney’s Aulani project was built in the teeth of Hawaii’s most severe economic turndown in a generation. When you add in other developments, timeshare generated more than $200 million in capital expenditures in the state during 2009 and 2010, according to the Hospitality Advisors report. This year, Toy says, the industry projects an additional $80 million, which means there are currently more than 3,000 new timeshare units in the pipeline. Hotels are another matter entirely.

“Looking back over the last few years,” says Marriott’s Welch, “the only lodging construction in the state has been timeshare. And over the next 10 years, we have a plan to spend about $1 billion on more timeshare development.” That plan includes projects that are currently partially built, like Koolina and Kauai Lagoons, as well as others on the drawing board. Similarly, Hilton is in the entitlement process on two new towers at Hilton Hawaiian Village, and is selling units at the Grand Waikikian.

Dan Dinell, vice president at Hilton Grand Vacations and chair of the Hawaii chapter of ARDA, the industry trade association, puts that in perspective. “I know of no pure hotel project planned anywhere in the state,” he says, “but there are several timeshare projects planned.” He emphasizes that by adding: “There’s nobody who would develop a stand-alone hotel now in Hawaii; it just doesn’t pencil out.” In other words, the future of Hawaii’s hospitality industry is timeshare and mixed-use.

That’s because timeshare is simply a better capital machine, says Mitchell Imanaka, principal of Imanaka Kudo & Fujimoto, and the former chair of the Hawaii chapter of ARDA, the trade association for the timeshare industry. “The business model,” he says, “has to be contrasted with the hotel model, where someone comes in and builds a project, and hopes that by branding it, they’ll have a certain level of revenue and visitors.” In other words, the developer’s capital is buried in the project, and it may take years of uncertain profits to extract it again. “But the timeshare model permits a developer to go to market, sell his interest, and generate capital to either replenish his coffers, or to make a profit on the sale.” No less important, the ability to extract capital early helps mitigate the risk in the project. “It’s a very compelling model,” Imanaka says. “Because the return is likely to be higher for the developer.”

Timeshare Taxes

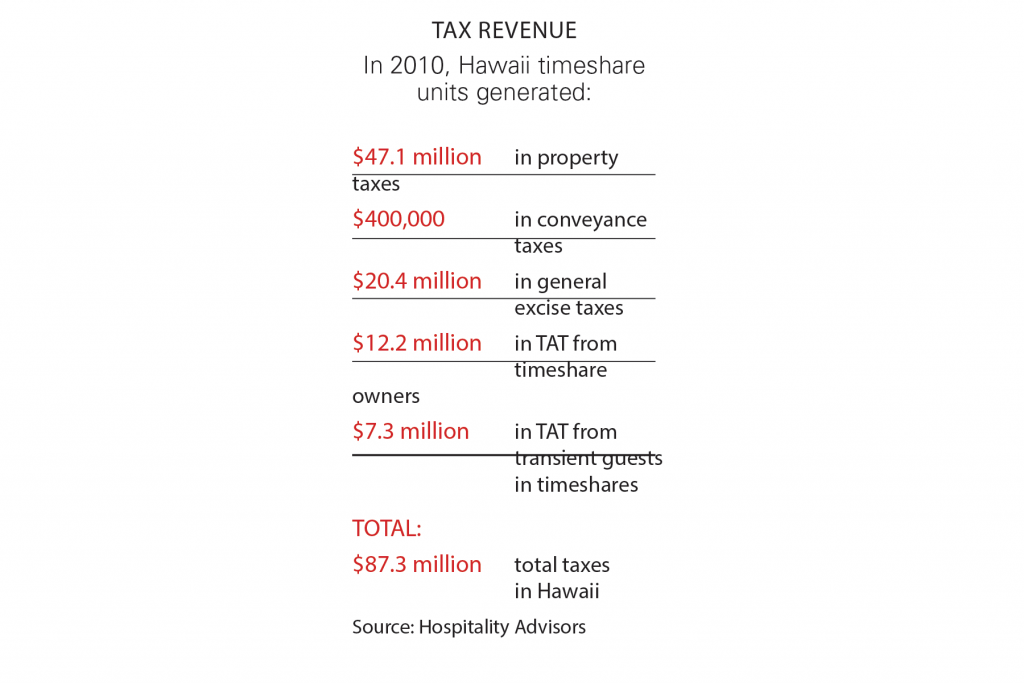

Despite timeshare’s growing importance in Hawaii’s hospitality industry, it’s still misunderstood. In January, Gov. Neil Abercrombie proposed legislation that would have more than tripled the transient accommodation tax paid by timeshare owners. According to the governor, this was an attempt to bring timeshare’s TAT in line with that paid by hotel guests. “The objective,” he said, “is to have equitable tax treatment to ensure that the people of Hawaii have adequate funds to support the impacts of visitors to the Islands.” In this sense, he believes the timeshare visitor and the hotel guest should be treated the same.

But industry advocates point out that timeshare owners are already treated differently. Toy says timeshare units already pay more taxes than comparable hotel rooms. For example, as a fee simple owner of real property, a timeshare owner pays property tax. When a timeshare unit is rented out as a hotel room, GET is charged. These visitors are also charged exactly the same TAT as hotel guests. Moreover, timeshare owners do pay a transient accommodations tax, albeit somewhat lower, when they use their own units.

It’s this last tax that industry insiders find most galling. To the governor, it’s simply a matter of equity. “In terms of sharing roads, public parks and hiking trails with our own residents,” Abercrombie says, “it doesn’t matter whether a visitor is staying in a timeshare or a hotel room – the impacts on our Islands are the same.” But the industry turns the equity question on its head. Marriott’s Welch puts it this way: “I believe Hawaii is the only state where a TAT is applied to people sleeping in their own beds,” he says.

Timeshare advocate Imanaka says another problem is what an increased TAT would say to outside developers. “The increase itself would have sent a very negative message to the timeshare industry, to the timeshare owners who visit Hawaii, and to the investment community who invests capital here,” he says. “We’re a capital-poor state, meaning we need to import money in order to keep things running here. The last thing we want to do is send a negative message to the investment community saying, ‘Your dollars aren’t welcome here.’ And that’s my fear: that this will have a chilling effect on investment here in Hawaii.”

Instead of hiking taxes on timeshares, Imanaka says, the state should be nurturing the industry. “If we did, we would not have budget shortfalls as dramatic as we’re experiencing today. We would not have Furlough Fridays; we would not have to look at closing social services, having to tax retirees’ pension benefits, having to tax away Medicaid reimbursements, and the list goes on. Timeshare is the answer; it’s certainly not the problem. And what we have to do is embrace it, make sure the industry continues to thrive. Because we all benefit from that.”

How Timeshare Works

For those of you who never sat through the slick presentation of a timeshare salesman, a review is in order: Timeshare is a form of fractional ownership in real property, typically a resort condominium. In most cases, developers sell this ownership in one-week increments, with the buyers getting rights to use the property for a specific week each year. That’s how some owners use their timeshare, coming back to the same resort at the same time every year. But there is often flexibility – the flexibility, for example, to trade weeks with another owner, either at your resort, or even in another state or country. Owners can also rent out their weeks or, in some cases, bank them for other years.

Upcoming Timeshare Projects

Average Hawaii Timeshare Weekly Maintenance Fee

High fees, which cover everything from property taxes to upkeep, are one of the biggest issues with timeshare owners.

Tax Revenue

In 2010, Hawaii timeshare units generated: