This Houseless Village in Wai‘anae Keeps Twinkle’s Vision Alive

Before she died, Twinkle Borge selected leaders for Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae. They’re holding the harbor community together as a permanent village is built.

Twinkle Borge was the leader and soul of Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae – the “Refuge of Wai‘anae” – and when she died in August, I worried about the future of her community of houseless people.

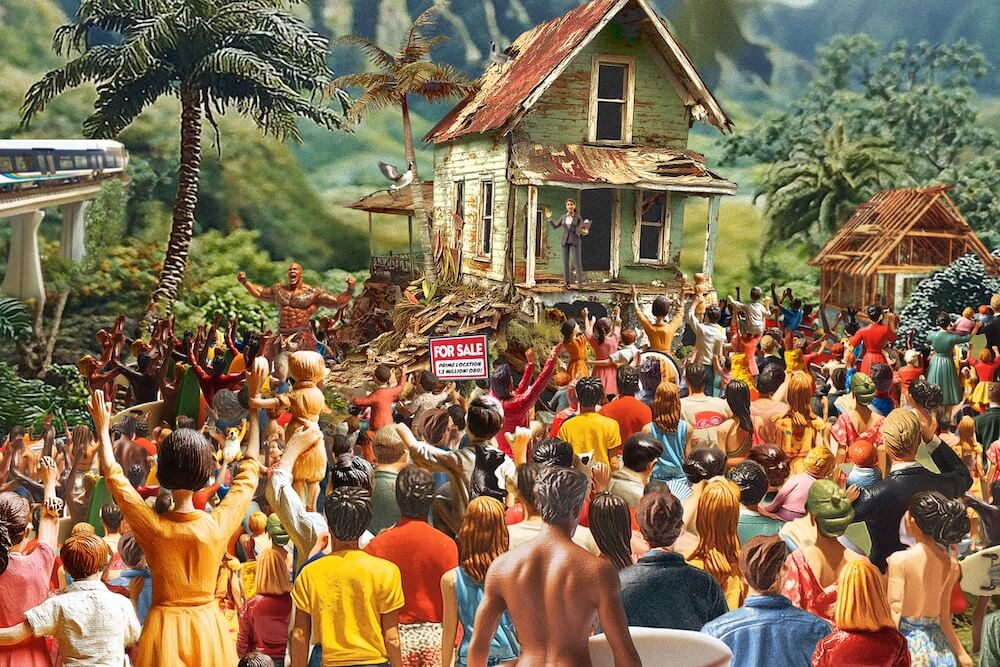

At Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae roughly 200 people, a quarter of them children, live in makeshift shelters next to the Wai‘anae Small Boat Harbor. But their dream was to build a community where they could live together in permanent homes, so they and their supporters raised $1.4 million – enough to buy 20 acres in Wai‘anae Valley in 2020. They named the place Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae Mauka, or just “Mauka” for short.

Residents say nobody could possibly fill Borge’s “big slippahs.” Nonetheless, construction has begun on the Mauka community, whose organizational foundation was laid by Borge.

Pia Bear is one of six overseers that Borge appointed before she died. Each of those overseers represents a different section of the village; Bear represents Section 1 at both the harbor and Mauka.

She is among the 18 residents of Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae who now live at Mauka. The handful of container homes they’re in now are temporary. As construction of more permanent homes is completed, more residents will move into the valley.

Bear moved up to Mauka a year ago but says she still visits the harbor village “almost every day. I have a sister who’s still there. I have a niece still there, and a great-nephew and a lot of friends.”

When I asked how the villagers are making decisions without Borge leading them, Bear says, “She already had it set in place. She had six overseers, and then she had her captains in each section, and then she had her co-captains in each section, and we just kept it the same way she had.

“So with the six overseers, they pretty much come together and make the final decision on the harbor. We vote, and as long as we get four votes, it’ll pass. And then up here, it’s just basically the people living here now that make decisions for Mauka.”

Bear says she tries to help solve problems when neighbors come to her. If they’re fighting, she says, she’s a mediator. “Up here, I collect everybody’s maintenance fees, give them receipts, make sure my neighbor’s OK, make sure nobody’s coming in and out during the night, making sure your home is safe and your neighbor is safe. To me, that’s just daily stuff.”

Still, Bear admits the community’s overseers are struggling to hold down the fort as well as “Mamas” did, using Borge’s nickname.

“We got a handful that’s just running wild right now, that don’t care, that won’t even listen. But as the six overseers, it’s hard to do what Mamas did, because all she needed to do was talk to them and they would stop. With us six overseers, it’s a lot more challenging.”

Turning a Vision Into Reality

James Pakele is the co-founder and president of Dynamic Community Solutions, a nonprofit that emerged in 2017 as an offshoot of Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae. Pakele says he’s never been houseless himself but, like many of the camp’s residents, he grew up in Wai‘anae in poverty.

He says his family was “lucky because we got to live Hawaiian homestead. We was poor too, but we still fortunate because we’re not sitting on the [Hawaiian Home Lands] list when plenty guys on the beach still sitting on the list and people dying on the list,” Pakele says.

He believes becoming houseless can happen to anybody: “You take the breadwinner in your household. One cancer diagnosis and you’re done. The breadwinner in your household driving to work, boom, accident. You’re done. You think it cannot happen to you, but it can.”

Pakele helped lead discussions with then-Gov. David Ige and other government officials, including a pivotal moment in 2018 when he, Borge and others persuaded Ige not to sweep the harbor village.

“We told him, ‘No break the community. Let us move,’ ” recalls Pakele. What Pakele and other community leaders proposed was ambitious: Raise enough money to purchase land and legally build permanent housing for Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae’s residents.

Ige was persuaded. “I appreciate that he believed us, because I don’t know if I would have believed myself if somebody was telling me what I was telling him,” Pakele says.

The first donor, Nareit Foundation, contributed $150,000, which was then matched through a challenge grant. That garnered media attention and more donations poured in. In just two years, Dynamic Community Solutions raised $1.4 million, enough to buy the 20 acres in Wai‘anae Valley known today as Mauka.

Cost-Efficient, Communal Communities

Construction, which began in 2020, is also being funded by donations and grants. Pakele says the community plans to build tiny houses in eight phases: The first three phases will each include six to eight duplexes that can accommodate about 25 people.

“Phase one is done,” says Pakele, and he hopes phase two will be completed in April. At full buildout, there will be enough housing for 250 residents.

The goal is to make the Mauka village cost-efficient, which means individual homes will not have kitchens and bathrooms. “If you pull those out of the house and you have them share that, then you’re building bedrooms, and that’s simple and easy,” Pakele says.

The plan is to build communal restrooms and kitchen spaces throughout the Mauka village, although Pakele says the community is still figuring out how many will be needed.

Mauka’s 24/7 indoor plumbing and electricity will be a major upgrade from conditions at the harbor encampment down “Makai,” where residents rely on portable toilets, costly generators and limited time frames when they can use the harbor’s waterspouts to shower.

Pakele says Dynamic Community Solutions received a grant from the federal EPA to install five microgrid systems to generate electricity from solar panels, and three containerized farming systems in which temperature, water and lighting can be controlled. “That is going to be super exciting because that is going to merge technology with agriculture, and we’re going to be able to introduce it to our kids,” he says.

“The idea is to make food cheaper and offset that cost, but also make the healthier choice, the cheaper choice and the easier choice, because it’s going to be more available.” And having high-tech ag on the property may also provide a lucrative business opportunity for residents to earn money by selling the produce they grow.

Pakele estimates the monthly rent will be about $200 to $250, but “if we can get microgrids put in here that offset the cost of electricity, that’s gonna come down significantly. I would love to be able to tell people only $100, $150, whatever.”

Although Mauka’s phase one is complete, organizers are still smoothing out kinks and finalizing terms of landlord/tenant leases for residents. Pakele expects residents will start moving into permanent Mauka structures soon, with kūpuna and those with disabilities getting top priority in phase two, which can accommodate them.

Pakele says Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae was the pilot project for the kauhale concept of communal villages for houseless people in Hawai‘i. He says it inspired kauhale villages “that they’re building all over the place. Going to help people. Please, please, do that.”

Pakele says there are three options for construction: “fast, cheap and good. Pick two, because you cannot have three. Fast and cheap not gonna be good. And good and fast not gonna be cheap.”

Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae prioritizes cost-efficiency and quality over speed. However, Pakele acknowledges that the community can take more time with the project since it’s not subject to the same public scrutiny that pressures government officials to complete tasks quickly.

Camping at the Village

Bear invited me to camp at the established village next to the small boat harbor so I could better understand what life is like there, and I jumped at the opportunity. It was culture shock. I had camped before, but just 24 hours living in a tent at the harbor made me better understand how hard it is to spend every day of your life without a cozy bed, hot showers, indoor plumbing, a stocked fridge and the security of a locked door.

That said, I rarely heard anyone complain about living there. Residents more often expressed how grateful they were to be a part of Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae’s community versus trying to make it on their own. I was also impressed by their resourcefulness in building makeshift shelters that they customize to feel like home.

During my stay, I shell hunted in the tidepools at the nearby beach with a few of the village’s keiki, played chess against (and lost) to longtime resident Shyann Rose, witnessed a glorious West Side sunset and spent hours talking story with villagers, including three siblings.

Twins Sandra and Kaulana are 11 and their sister, Haweo, is 9. They came to the village with their father in 2020. Kaulana said he likes living there, for the most part, because “it’s fun to meet new people.” But being houseless also makes them targets for bullies at school.

“A bunch of bullies tease me, saying that I’m homeless. … [But] my friends don’t treat me like that,” says Kaulana. Haweo adds that their teachers often remind them, “We don’t have a real wall and a roof, but this is still our home.”

I asked them about their aspirations. “When I grow up, I want to graduate college and be a photographer,” Haweo told me.

Kaulana added that he wants to have a successful life. “I want to graduate college and get a job so I can buy a house for me, my dad, my sisters. … One really big house for all of us to sleep in – with AC.”

After five years of living in the village by the harbor, the siblings and their father will soon move into a tiny house together in Mauka – a milestone that honors Borge’s legacy and vision.

Borge loved her community’s keiki and sought to break the cycle of generational trauma and homelessness.

“It’s not their fault; it’s their heritage,” she told me in 2023. “I want to go above and beyond to show them they can do better, that you can do it, you can make it happen. But you have to want it.”

To donate to Phase 2 of the tiny homes village being constructed in Wai‘anae Valley, please go to https://www.gofundme.com/f/phase-2-puuhonua-o-waianae.