These Canoes Virtually Connect UH Campuses

At UH, you can walk into a classroom on the West Oahu campus to take a course on video game development with students who are 20 miles away in Manoa.

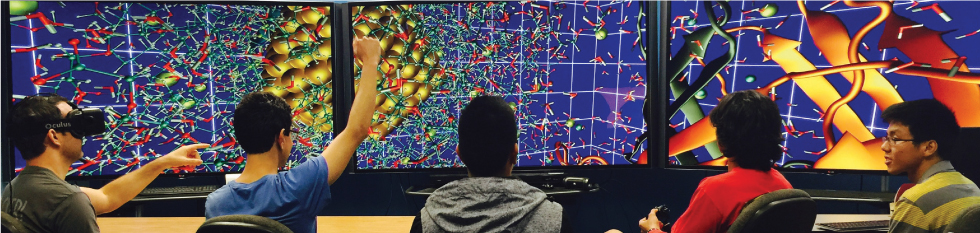

Forget what you thought you knew about distance learning. These student-developers aren’t passively watching a lecture or talking via teleconference. On both campuses, students and teachers sit in virtual-reality environments called CyberCANOEs that bring the two classrooms together.

“Imagine it being Skype on super-steroids, Skype as you would only see it in the movies,” describes Jason Leigh, who developed the proprietary software that creates the collaborative environment. The students aren’t just seeing video of the classroom or sharing desktops. Through the CyberCANOE, which stands for Cyber-enabled Collaboration, Analysis, Navigation and Observation Environment, they can work with each other on shared projects despite being on separate campuses.

The CyberCANOEs are filled with high-resolution LCD screens. Each student sits at a desktop computer while large monitors line the walls, displaying video from the two classrooms or projecting what the students and teachers are working on at their desks. Leigh compares it to a war room that you might see on film or TV, with the walls covered in electronic data. “It’s almost surreal, but the reality is that students are now using this technology to develop these projects, like in a video game class,” Leigh says. class,” Leigh says. It’s great for a dual-campus class in video game design, but a CyberCANOE has the potential to do much more. “One of the things that’s holding Hawaii back is it’s so isolated. We need these connections to the mainland to draw ideas back to Hawaii and expose students and teachers to new ideas,” Leigh says. “Faculty and researchers can work on joint projects together over distance. They can see what they’re doing and see each other.”

Leigh, 49, began writing video games in the 1980s, working on Apple IIs and early Commodore machines while he attended high school in Hong Kong. “Computers were so new back then, no one knew whether you could make a living off them,” recalls Leigh, who is now founder and director of the Laboratory for Advanced Visualization and Applications (LAVA).

He returned to the U.S. for college and dropped chemical engineering to major in computer science. He’d always planned to move to Hawaii, but, until last spring, he’d been a faculty member at the University of Illinois-Chicago. There he created a virtual environment called CAVE2, a 2-D and 3-D 320-degree panoramic, virtual-reality environment.

“IMAGINE IT BEING SKYPE ON SUPERSTEROIDS, SKYPE AS YOU WOULD ONLY SEE IT IN THE MOVIES.”

— JASON LEIGH, DESCRIBING CYBERCANOE

Leigh says CAVE is currently sold commercially through Mechdyne as the leading immersive virtual reality environment, used by companies such as defense contractor Raytheon Corp. so designers can collaborate from remote locations.

Students navigate through a 3D chemistry simulation on the CyberCANOE.

A CyberCANOE is a scaled-down version of Leigh’s CAVE2.

Chris Lee, director of UH’s Academy for Creative Media, helped fund Leigh’s CyberCANOE project and the two are working together on other initiatives.

Lee saw video-game design as something ACM should get into from the start and he’s excited that Leigh’s software tool got the ball rolling at Manoa and West Oahu. They’re in the process of expanding to the UHHilo campus, as well. “This relies on Jason’s own proprietary software. I’m thrilled to bring his knowledge to the classroom and his teaching skills to more than one campus,” Lee says.

Lee thinks Hawaii’s creative media industry could benefit from more video game development. The industry is still mostly focused on location-based models, like the “Hawaii 5-0” production, without doing much post-production work, animation or video game development. “The films are one side of what we’d be doing, but the things you’d be doing on a computer have a much bigger upside,” Lee says.

He adds that manufacturing isn’t really a feasible industry in Hawaii, except for the manufacturing of ideas and creative intellectual property.

“We don’t seem to be out there competing for these businesses,” Lee says. But that could change if more students graduate with the skills to get into film or game development. Mobile gaming, in particular, could take off in Hawaii since it requires a small team – often just one person. Lee points to the huge success of the mobile game Flappy Bird as an example of how a relatively simple game can gain huge popularity. “We want to create these games. They’re simple but they’re good.”