The New Culture of Giving

Hawaii’s people and businesses are as generous as ever, despite the economic slump.

But how local people and businesses give is rapidly changing and that transformation has some nonprofit leaders heartened, while others are worried. Optimists welcome the decay of what they saw as paternalistic philanthropy – where nonprofit leaders told contributors: “You donate the money and we’ll figure out where the needs are.” These optimists see the rise of a new philanthropy in which individual donors are more empowered, and nonprofit success is rewarded with recognition and more donations.

Other nonprofit leaders, however, worry that these changes in giving might mean that important – but unsexy – community needs are forgotten.

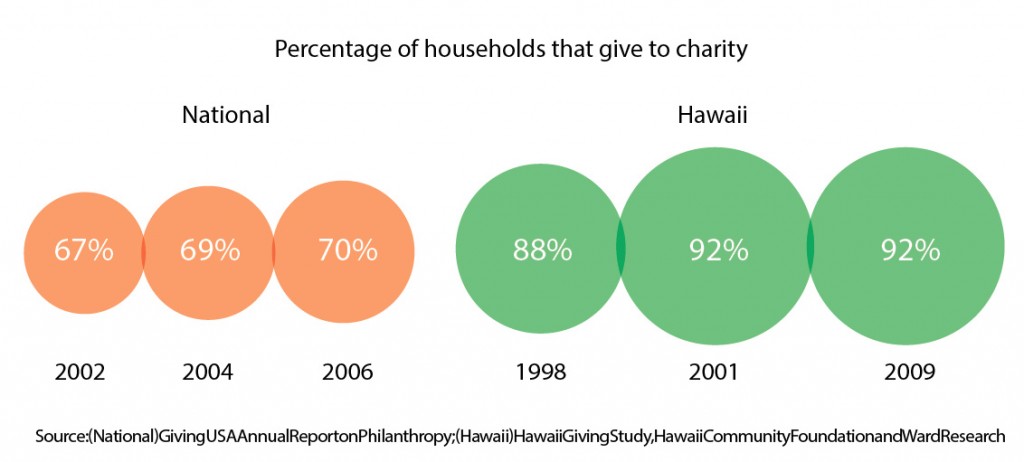

An astounding 92 percent of Hawaii households donated to charities in 2009, a proportion unchanged from 2001, according to the Hawaii Community Foundation’s Hawaii Giving Study. That’s much higher than the national average of 70 percent. The average amount given annually by Hawaii households – $1,467 – is actually 2 percent higher than in 2001 when adjusted for inflation, says the foundation’s study, which was conducted by Ward Research.

But, while overall giving remains largely unchanged, the way people give in Hawaii has morphed and will continue to evolve. Here are some of those important changes:

A virtual, giving community:

The Hawaii Community Foundation, by far the biggest and richest grant-giving and -receiving nonprofit in the state, is about to launch an Internet-driven initiative that will create a new community of givers, volunteers and organizations.

This virtual community will decide what works, what doesn’t and where the money will go. The issue is: Can the same technological and social forces that drew millions of people to Facebook, Twitter, eBay and the Internet itself also transform local charitable giving?

Last year, Pierre and Pam Omidyar announced they would commit $50 million to the foundation, with part of that money aimed at spurring innovation in the nonprofit and public sector in Hawaii. This Omidyar Innovation Fund will give matching funds for creative, new projects, and it will also help create an online giving community.

“The idea is not so much for fundraising as to be a marketplace for ideas,” says Kelvin Taketa, president and CEO of the foundation.

Here’s how it works:

• You go online and find a charity or nonprofit you admire from the hundreds or thousands listed;

• copy their strategies; or

• volunteer; or

• give money; or

• adopt their ideas as your own.

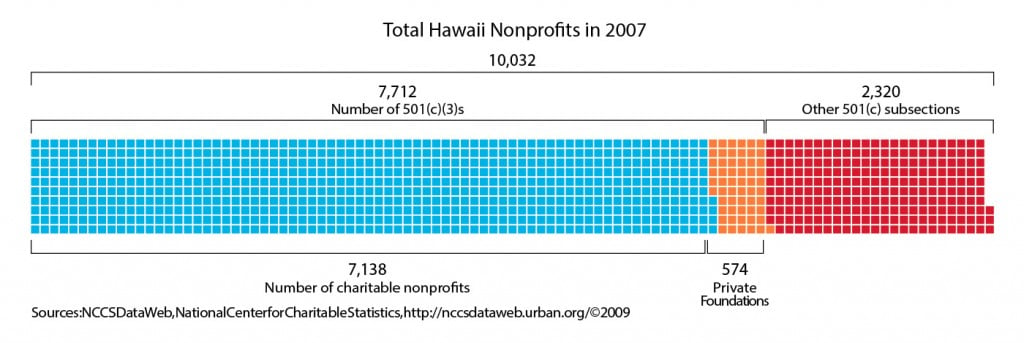

There were 10,032 nonprofits in Hawaii in 2007, the latest year for which that figure is available, according to the Hawaii Alliance of Nonprofit Organizations. Of those, 7,712 are 501(c)(3) charitable nonprofits and 574 are foundations that give money to nonprofits.

People who want to target a specific cause can designate their donation to one of the Aloha United Way’s five “impact areas,” says AUW President Susan Au Doyle. | Photo: Kevin Blitz

Today, most nonprofits struggle to survive day-to-day and many operate in isolation. The connectivity provided by this charity marketplace might change that. Here’s how the foundation put it in a prospectus:

“Networks are altering the way the world works, shifting from organization-centric models with centralized structure, closely held knowledge and a focus on organizational longevity to network-centric models that value decentralization and fluidity, openness and a rapid pace of connectivity and mobility.”

Read that paragraph a few times and you will understand where the foundation is headed.

“It may work, it might not,” Taketa acknowledges. “But change is inevitable.”

In many ways, businesses are taking the lead in this transformation.

“People like (Bill) Gates and (Warren) Buffett are changing consumer behavior on how giving is handled,” he says. “The old model has been left behind. That model was: ‘You sign, I’ll figure it out.’ It’s different now. Business is trying to narrow its focus to something that is strategic or useful to them. It’s a different kind of engagement.”

Decline of umbrella charities’ share

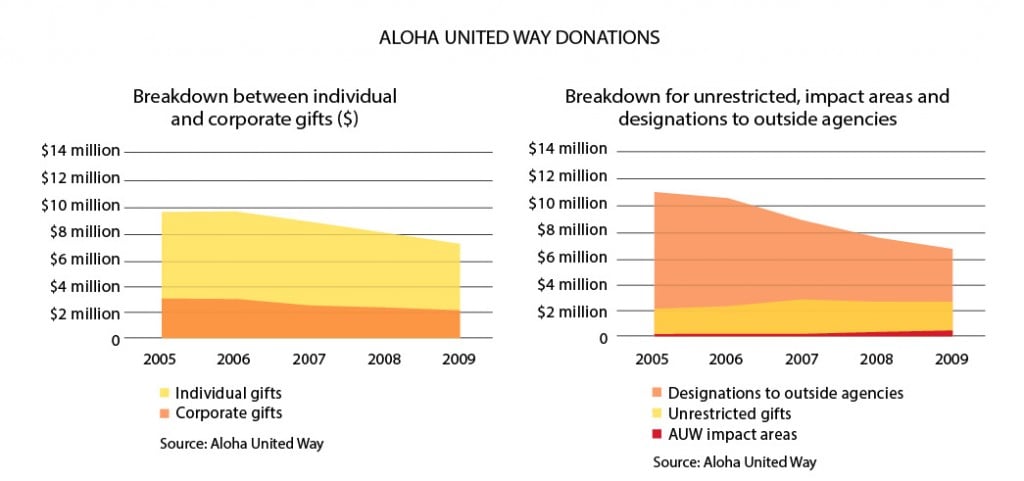

Overall dollars to the big “legacy” nonprofits are down. For instance, the Aloha United Way reports that total contributions in 2009 were 26 percent below 2005. Both individual and corporate donations to AUW were down about equally in percentage terms.

But drilling deeper into the AUW numbers, you find that the proportion of donations targeted for specific charities or causes has actually increased from 17 percent to more than 27 percent. More and more people designate where their contributions go, rather than just making a general contribution to the AUW.

“The trend is to targeted giving,” says John Howell, CEO of Easter Seals Hawaii. “In the past, you really just kind of trusted people to make good decisions with your money. Now it is more of a personal engagement. It’s building a relationship with donors.”

That thought was echoed by Laura Robertson, CEO of Goodwill Industries of Hawaii. “People want to know: Are our donations going to services we support?”

In 2005, the AUW raised a total of $13.2 million – three-quarters came from individual gifts and one-quarter from corporate donations. By 2009, the split was about the same, but the overall amount raised was down to $9.3 million. Adjusted for inflation, the decline was even greater.

In recent years, the AUW has shifted from an individual agency focus to a focus on five “impact areas:” crime and drugs; early childhood development; emergency and crisis services; financial stability and independence; and homelessness. There as been a small but steady increase in gifts in money donated specifically for the impact areas, says Susan Au Doyle, president of Aloha United Way.

“We encourage people, if they want to do something specific, to give to one of our (impact) areas,” she says.

“Overall,” she says, “giving has gone down. But you really can’t tell if people don’t like the United Way anymore or if they’re just giving in different ways.”

Business donors change gears

Companies, big and small, are finding new ways to target their donations and to promote giving by their employees.

That cultural shift is driven both by technology and the desire by both individuals and corporations to have more of a say in how their donations and volunteer hours are used. In some cases, these changes in giving are also designed to help the company succeed in its everyday business.

Here’s how three local companies have changed their charitable focus.

• First Hawaiian Bank: The state’s biggest corporate giver was formerly a major player with the Aloha United Way. Now, the bank manages its own giving program, Kokua Mai, which encourages employees to donate to causes they feel make the most sense. Much of First Hawaiian’s and its employees’ money still goes to United Way or to organizations AUW supports, but First Hawaiian is no longer a direct participant in the AUW effort.

“We just felt we could get better participation if we handled it in-house,” says Don Horner, chairman and CEO. First Hawaiian has a deeply embedded culture of giving and community involvement, and bank officials felt that the Kokua Mai program offered a “clear line of sight” from individual employees to that corporate ethos, Horner says.

AUW and its affiliated agencies still receive the largest share of money collected by an employee-driven committee, Horner says. But this hands-on approach has another benefit, he says. It keeps the bank in close touch with the communities it serves, whether they are in Hawaii, Guam or American Samoa.

“Our focus is on investing in our neighbors,” Horner says. “After all, we are in the lending business and you have to understand the community and what’s going on.

“We see philanthropy as an investment and we take that investment very seriously. That’s what bankers do. The return on that investment, in terms of our employees, is that they have a better perspective on life; they grow individually and corporately and get skills they might otherwise not get.”

–Don Horner, Chairman and CEO, First Hawaiian Bank

“We see philanthropy as an investment and we take that investment very seriously. That’s what bankers do. The return on that investment, in terms of our employees, is that they have a better perspective on life; they grow individually and corporately, and get skills they might otherwise not get.”

The bank also gives through its foundation, mostly for capital projects, and individual branches are encouraged to give to activities in their immediate community, such as Little League or neighborhood fundraisers.

• Pacific Office Properties: The commercial real estate and property management firm founded by businessman and philanthropist Jay Shidler last year launched a program in which it gives two $500 increments annually to every employee to donate as they wish.

FedEx Kinko’s manager Kattie Kaauwai-Chess helped teach children at Kalihi Waena Elementary about traffic safety during a walk-to-school day. FedEx encourages employees to volunteer in their communities. | Photo: Kevin Blitz

It’s called Pacific Cares, and recipients must be qualified tax-exempt organizations qualified to receive charitable contributions. But, otherwise, the company takes no role in deciding where the money goes.

“In the past,” says office manager Joy Hessenflow, “Jay would write a check and that would be it. He is a huge giver, but he was looking for a way that employees could participate and get more involved.

“I have people who contact me and say in the past you have given to this event or that charity and I have to say we have changed and now our donations are employee-driven,” Hessenflow says. “It has changed to a very much more personal thing because now employees have their radar up, their eyes and ears open. It’s not just going to those who have the most influence or whose name is well-known.”

• FedEx/Kinkos: While money is an important part of any giving program, there are other ways in which a business can contribute to the community. One example is FedEx/Kinkos, which has a very active program of employee participation and volunteering in community activities.

Kattie Kaauwai-Chess manages a FedEx/Kinkos branch in downtown Honolulu. But she spends much of her time volunteering or organizing fellow employees to donate their time or money.

“I’m gung ho on this,” she says. “A lot of it has to do with just watching out for your team. If people are happy, they are not afraid to stay late for each other. And it’s not just what you do at work, it’s the other things you do together as well. When you get involved in these activities, you see these other people and you get to know them. It allows people to shine. And that helps at work.”

While the FedEx effort is a very local, ground-up style of volunteering (making bento lunches for a charity walk, for instance), it is also part of the overall corporate culture, Kaauwai-Chess says. “It’s a vision our company really believes.”

“When you and your co-workers get involved with something like the March of Dimes, you feel: ‘I’m here with my friends.’ ”

“It’s a powerful thing.”

Why Give?

Why do businesses and corporations give at all? The quick answer is that as members of the community, they are obligated to give back, to help create a healthy community in which to operate. Fair enough. But there are other motivations as well.

A recent national study by McKinsey & Co. of nearly 800 top executives worldwide found that the reasons for corporate giving were complex, interrelated and subtle. While the vast majority said the major benefit of corporate philanthropy was enhancing the corporate reputation or brand, there were many other observed benefits as well. Among them:

• beefing up employee leadership capabilities or skills;

• boosting employee retention or hiring; and

• building knowledge about markets and customers.

In short, the business leaders agreed that a culture of giving is not just a good thing to create and nurture, it is good for business as well.

United Way’s Biggest Backers

Here are the Aloha United Way’s largest financial supporters in 2008:

$1 million to $750,000

Bank of Hawaii

Hawaiian Electric Industries (including subsidiaries)

$750,000 to $500,000

State of Hawaii, including executive, legislative and

judicial branches

$500,000 to $250,000

Atherton Family Foundation

City of Honolulu

State Department of Education

First Hawaiian Bank (including subsidiaries)

Gates Family Foundation

Hawaii Medical Service Association

Servco Pacific

University of Hawaii System

AUW also recognizes smaller organizations that give generously in the category of Small Business/Big Heart

$15,000 to $10,000:

AAA Hawaii

Assets School

Associated Steel Workers Ltd.

Bowers + Kubota Consulting

CH2M Hill

Cronin Fried Sekiya Kekina & Fairbanks

Hawaii Employers Council

Honolulu Publishing Ltd.

IBEW Local 1260

KPMG

Pacific Business News