The High Cost of Affordable Housing

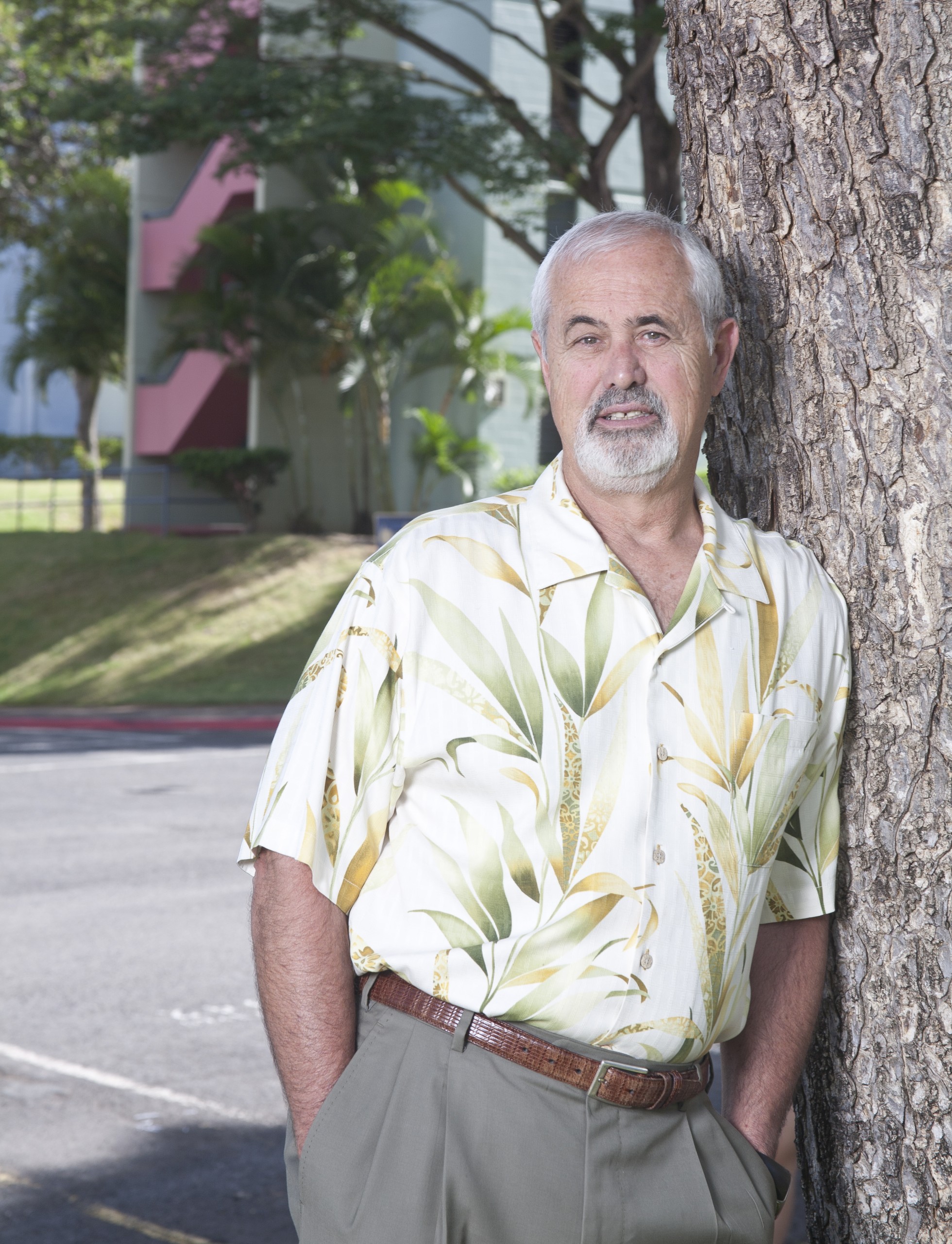

“Building affordable housing is complicated,” says Makani Maeva.

She should know. As Hawaii director for the VitusGroup, an affordable-housing developer, she recently completed the Lokahi Apartments, 307 rentals in Kona. Between January 2007, when another developer laid the project in her lap, and July 2010, when the apartments first were offered for rent, almost all the financial and technical details of the deal changed dramatically: The permanent loan went from $16.4 million to $19.2 million; the original equity investors – GMAC, Wachovia and others – had to be replaced; $7.8 million in affordable-housing credits from the County of Hawaii became unavailable, replaced by a soft mortgage of $11.75 million from the state’s rental housing trust fund; and the cost of construction rose from $53 million to $60.6 million, largely due to interest costs.

“It’s like fried rice,” she says. “Because I thought I had one thing in the refrigerator, I thought the project was going to be structured one way.” In the end, though, the recipe changed completely.

The complexity of Lokahi’s financial arrangements is hardly unique. In fact, the average affordable-housing project in Hawaii is funded by at least seven financial instruments – industry insiders say some projects require as many as 14 – each of which comes with its own rules. That’s just the financing. The truth is everything about affordable housing is complicated and constantly changing – the money, politics, regulations, ethics. If you want to “fix” the system, you have to consider them all.

Makani Maeva, Hawaii director for the VitusGroup, knows from experience that the financing for an affordable housing project can change dramatically before it is finished. | Photo: Rae Huo

What is ‘affordable housing’?

Too often, affordable housing is equated with public housing and poverty. But the affordable-housing crisis affects a broad swath of the middle class. Developer Chuck Wathen, who recently founded the Hawaii Housing Alliance and is a longtime advocate for affordable housing, notes it would take 3.19 firemen to be able to afford the median-priced home on Oahu. It would take 3.63 school teachers or 5.2 hotel front desk clerks. “What we have isn’t just an affordable-housing problem,” Wathen says. “We have an income problem.”

He also notes that the shortage of “workforce housing” is most acute in the rental market: “A Mainland city of this size would probably have 400 apartment communities of over 300 units.” Yet there’s no financial incentive to fill this gap.

Kevin Carney, Hawaii vice president of EAH, a nonprofit affordable housing developer, explains the math. “It just doesn’t pencil out to do a rental project,” he says. “Let’s say you’re serving a market segment at 100 percent AMI (area median income) – a family of four that makes $80,000 a year or so. The rents you can charge at that income level just aren’t going to cover your debt and operating expenses. So you can’t build it. Instead, you build a condo and you sell those units to people with incomes of, say, 200 percent AMI or more. Then they turn around and rent them out as long-term investments.

“That’s our ‘shadow’ apartment market in Hawaii.”

The financial puzzle

Government programs account for almost all affordable-housing development, either through subsidies or by regulations that require developers to include affordable units in their market-priced developments. But neither approach has supplied much housing in the past two decades.

The centerpiece of affordable-housing finance is HUD’s Low Income Housing Tax Credit, which is administered in Hawaii by the Hawaii Housing Finance & Development Corp. LIHTC (pronounced Lie-Tech) was created to spur the private development of affordable housing, awarding dollar-for-dollar tax credits in exchange for guaranteeing a project will remain affordable for at least 20 years. By some estimates, LIHTC has played a role in the development of as much as 90 percent of all affordable-housing units in the country. Hawaii is no different.

The VitusGrouprecently completed the Lokahi Apartments, 307 affordable rentals in Kona. | Photo: Vitusgroup

Darren Ueki, HHFDC’s finance manager, explains that there are two kinds of LIHTC credits, one worth 9 percent and the other 4 percent of a project’s development costs. “We’re basically giving out anywhere from $27 million to $28 million in (9 percent) tax credits a year.” Yet he acknowledges that demand for affordable housing is much greater than that. In 2007, an HHFDC report projected the state would need to create more than 28,000 rental units over the following five years. Even by the most liberal estimates, the LIHTC program creates fewer than 300 units a year in Hawaii. That’s not surprising, since those credits only account for a small fraction of the cost of development.

For example, the credits don’t cover the cost of the land or predevelopment planning. (Developers say that, for an affordable-housing project to work in Hawaii, the land must essentially be free.) In addition, the developer must find investors with tax liabilities to purchase the tax credits. During the housing bubble, developers sold credits at nearly face value, and sometimes higher. Once the credit markets crashed, the prices plummeted to 60 cents on the dollar, though they are back to about 90 cents. Typically, the proceeds from these sales account for nearly all the equity in an affordable-housing project. “The problem,” says Carney, “is that will only produce between 30 to 40 percent of your equity needs. So you’ve still got to come up with the other 60 to 70 percent.” That, too, is affected by LIHTC rules.

For example, there’s the property’s income stream, the money earned from rents or sales. As in a market-price project, the affordable-housing developer can borrow money against this revenue, but the project’s income is restricted by HUD regulations, which limits the amount of rent (or mortgage payments) the developer can charge to 28 percent of the customer’s monthly income. At 60 percent AMI, for example, a two-bedroom unit at the Lokahi Apartments rents for only $833. That’s what makes it affordable. But these rent rules limit the property’s income and the debt it can support. Moreover, the lender will usually only permit an 85 percent debt-to-income ratio, reserving the remaining 15 percent as cash flow to cover operating costs and profit. Thus, the $60.6 million Lokahi Apartment project could only secure $19.2 million in permanent financing, less than a third of the development’s total cost. The balance had to be painstakingly cobbled together from federal and state subsidies and loans. In fact, for the typical two-bedroom affordable rental unit, the state has to kick in another $150,000.

Putting the financing together is a slow process. One EAH project in Ewa has been in planning for 10 years. Maeva eschewed the cumbersome 9 percent LIHTC credits altogether, opting instead for the state’s low-interest Hula Mae loan program, in which HHFDC issues tax-exempt bonds to help finance affordable-housing projects. An added bonus is that participants automatically qualify for 4 percent LIHTC tax credits.

Regulatory dance

Government regulations also provide incentives for and hindrances to development. For rental properties, the most important are the federal, state and county regulations that affect the affordability period of a development. Since any affordable-housing project exists only because of public subsidies, it seems fair to require the developer to keep the project affordable for a reasonable period. Of course, “reasonable” means different things to different people, and today it ranges from 20 years to 60 or more.

The need for these rules became clear in 2006 when the owners of the state’s largest affordable-housing project announced plans to sell when it came out of its 20-year affordability period in 2011. The planned sale of Kukui Gardens by the Clarence T. C. Ching Foundation would have put nearly 2,500 tenants out of affordable housing. Only the investment of more than $50 million by the state – along with extensive tax breaks and bond support and a partnership with nonprofit developer EAH – preserved the project. But EAH vice president Carney acknowledges Kukui Gardens is just the tip of the iceberg. “The low-income rental industry loses two apartments for every one that’s being built.”

Some affordability advocates, like Chuck Wathen, argue that the affordability period for rental housing shouldn’t end. Maeva isn’t one of them. “I say things shouldn’t be affordable in perpetuity,” she says, “because, if there’s no risk the thing will become market (rentals), then there’s no incentive to go in and rehabilitate it. What you’re then creating are really ghettos and public housing. You need to identify and recognize the finite lifecycle of a piece of wood and the termites’ appetite for that. If there’s no risk it’s going to turn into condos, then it’s not going to get any political attention. It’s not going to get any attention from new developers. And, at some point in time, everything needs to get redeveloped.”

Although Wathen clearly admires Maeva, he’s not convinced by her arguments. “Let me explain it to you this way,” he says. “When you develop these projects and you sell the tax credits to the investor, after 10 years, when they’ve got their write-off, they don’t want to hear about this project anymore. They want it off their balance sheet. They want to get rid of it. That means the developer gets the residuals of whatever you make after 15 years.” He says the Ching Foundation got a $148 million windfall from Kukui Gardens. Wathen asks, “Should private developers profit from public investment?”

Housing Alliance, thinks that private companies should not be able to profit from public subsidies that make affordable housing possible. | Photo: Kevin Blitz

The affordability period of rental housing has its analogs on the for-sale side. There, in exchange for opportunity to purchase below market-rate housing, the buyer agrees to terms like buy-back provisions and shared appreciation equity. Buy-back provisions give HHFTC the right to buy the property back at a designated price if the owner chooses to sell within 10 years. This strategy prevents flipping. Similarly, the shared-appreciation equity program requires the owner to share any appreciation in equity with HHFTC when the property is sold. The percentage share is established in the sales contract, and unlike the buy-back clause, never lapses. Like the affordability period, these tools are designed to preserve affordable housing.

In many ways, though, the availability of for-sale affordable housing is much more affected by state and county regulations that require a developer include a certain percentage of affordable housing in market-rate development plans. In Honolulu, this so-called inclusionary housing requirement is usually 20 percent. For the most part, these rules apply to any developer seeking rezoning or a variance, and the logic is clear: In exchange for the public’s permission to build, you must contribute affordable housing. But it’s not clear at all that inclusionary housing has resulted in more affordables.

Even Carney notes: “The tradition in Hawaii has been for major developers – your Castle & Cookes, your Gentrys – to supply the for-sale product of workforce housing. But nothing is free. They pay for that by increasing the cost of market housing.” Which raises an ethical question: If we, as a state, decide that affordable housing serves a critical community need, shouldn’t the costs of that service be born by the community at large? Yet, as Carney notes, under the current system of inclusionary housing, those costs are placed only on the other residents of the new development. This not only puts an unfair burden on new buyers (or renters,) the added cost is also a disincentive to building affordable housing. If 20 percent of your units have to be subsidized (to the tune of $150,000 each), it’s hard to make enough profit on the remaining units to justify the investment.

Is there another way?

Other strategies have been tried. During the Fasi administration, the city was a successful developer of affordable housing. Projects like Chinatown Gateway Plaza, Hale Pauahi Towers and Marin Tower in Chinatown are testaments to the viability of mixed-income development. Similarly, the controversial project proposed for River Street is also on city land. It’s true that those earlier projects were built when the city was flush and there was a civic commitment to affordable housing. Nevertheless, city development might be updated to suit the needs of today. Certainly, spreading the cost of affordable housing across the tax base is more equitable than foisting it on a few new buyers. It’s also less likely to discourage market-rate development.

The state has also been an affordable housing developer. Twenty years ago, when it began development of the Villages of Kapolei, it built out the infrastructure and provided developers with ready-to-build sites. In exchange, the state required those developers to make 60 percent of their units affordables. This project created thousands of affordable units, although, in practice, the 60/40 split didn’t work out financially for the developers. Nevertheless, the process might help circumvent some of the lengthy and costly aspects of getting permits and entitlements.

It may be that the best hope for increasing affordable housing is simply to make it easier for developers, even market-rate developers, to build. If you ask affordable-housing developers – whether specialists, like EAH and the VitusGroup, or large-scale community developers like Castle & Cooke and Stanford Carr – what’s the biggest problem in creating affordable housing, almost unanimously they say it’s the shortage of entitled land. That’s why there simply aren’t enough homes being built. Bruce Barrett, executive vice president for Castle & Cooke, puts it this way, “From a developer’s perspective, the lack of supply is the major issue that limits affordability.” He points out that, during the last housing bubble, the median home price on Oahu essentially doubled. “Why did it double? Because we’re building less housing stock now than we did in the 1950s.”

Which is not to say that subsidies don’t have a role to play. Jesse Wu, vice president at Stanford Carr Development, which has major affordable-housing projects in both Kakaako and Ewa, says, “The production of affordable housing is really limited by the amount of subsidy available. For most of these units, even when the land is free, we’re putting together $80,000 to $100,000 per unit to bridge the differential between what it costs to build the unit and what we charge as affordable rent.”

Courage of their convictions

Another impediment to affordable housing is when politicians and bureaucrats get in the way. During the early stages of the Lokahi Apartments project, Maeva voiced two common frustrations when the Hawaii County Council considered delaying a rezoning vote. “I said, ‘Pardon me, but everyone here acts like you’re into affordable housing, acts like you think it’s a need. Everybody got a bruddah bruddah who lives in a car, everybody got somebody no more job, everybody got a story. I say, to do nothing is a vote ‘No.’ It should go on the record that you’re against affordable housing.’

“ ‘You’re trying to make me solve all kinds of other problems. Saying, ‘Oh, there’s going to be increased traffic because of this affordable housing;’ ‘Oh, you need to increase the sewer system;’ ‘Are you sure we don’t need more parking?’ But I’m not here to solve every problem you have in the County of Hawaii. I didn’t create them and I’m not making that kind of money. I’m saying I can help you solve your affordable-housing problem; if there are other problems, that’s your kuleana.’ ”

In other words, shut up and let me build.

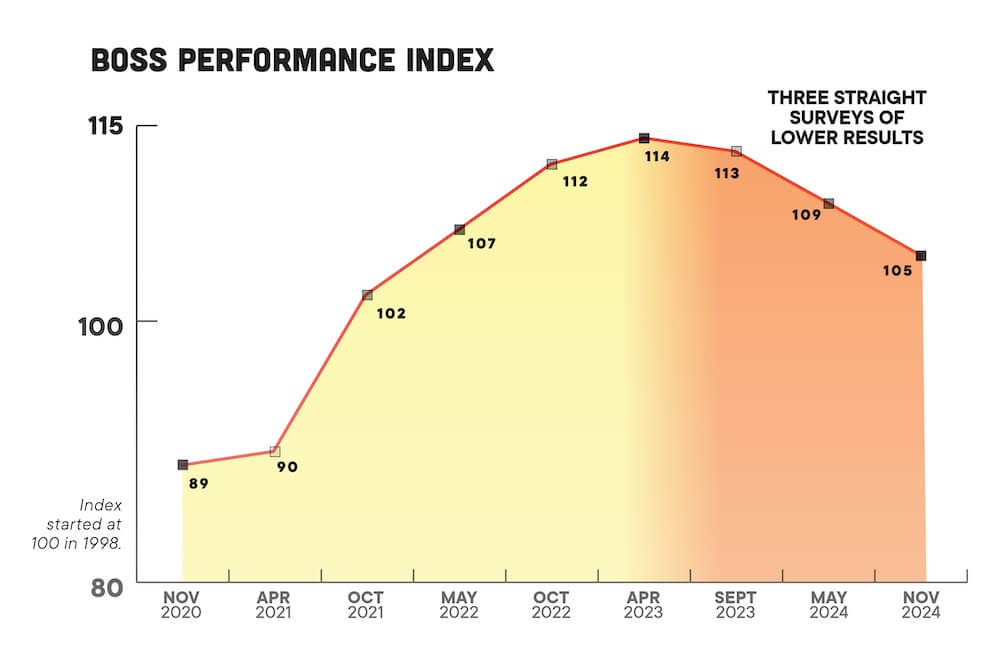

How Many Jobs Does It Take?

Developer Chuck Wathen says this may salaries are needed to afford a median-priced home on Oahu ($645,000 in August).

Lokahi Apartment Project

Where the funding came from