The Growing Crisis of Student Debt

Ryan Delaney had been teaching at Waianae High School for two years when he received an offer he couldn’t refuse: Return to UH-Manoa’s Speech Department to get his M.A. at a discounted price.

While earning that degree, he served as a teaching assistant for Public Speaking 251, a position he calls “the most hands-on TA I’ve heard of in college.” He speaks with fervor about the class content: “Presentation skills are what people need to know in almost any industry and down to things like dinner parties or eulogies.”

But when we change the subject, Delaney’s mood turns dark: His debt from undergraduate and graduate degrees now totals more than $80,000.

“I haven’t really looked too extensively at what options I have,” he says despondently. “It’s just been a black cloud over me. I don’t really want to think about it. I just push it out of my mind.”

Delaney has a lot of company for his misery and the numbers get worse each year:

• 40 million Americans are paying student loans today from their time in college, estimates Experian, the information-services and credit-monitoring company.

• The average former student with college loans owes somewhere between $32,264 and $37,672, depending on the source.

• Their total debt topped $1.3 trillion dollars in December 2014, according to Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

• The Fed also says student loan debt is now the largest category of household debt after mortgages – 9 percent of all household debt that Americans owe, surpassing auto loans and credit cards. And student debt’s share of America’s overall debt keeps growing.

This burden is not just a crisis for the former students and their families, but a huge weight on the national economy and society itself. Student debt discourages millions from buying homes and cars, making risky career moves, investing in stocks and 401(k)s, and getting married and having families. Debtors can’t devote themselves to unpaid or poorly paid public service if they can’t repay their loans. And, under federal law, student debt – unlike most other forms of debt – cannot be discharged in bankruptcy.

Today’s high school graduates face a dilemma: Overwhelming evidence shows that college graduates earn far more on average over their lifetimes than nongraduates, but the skyrocketing cost of college creates a huge burden of debt for many members of the working and middle classes. Nonetheless, education is seen as a shrewd investment in times of trouble. Even when people stopped buying houses and cut up their credit cards in the dark days of the recession, college enrollment rose a total of 6 percent during 2008 and 2009, the sharpest increase in a decade.

America’s youth borrowed to invest in their future.

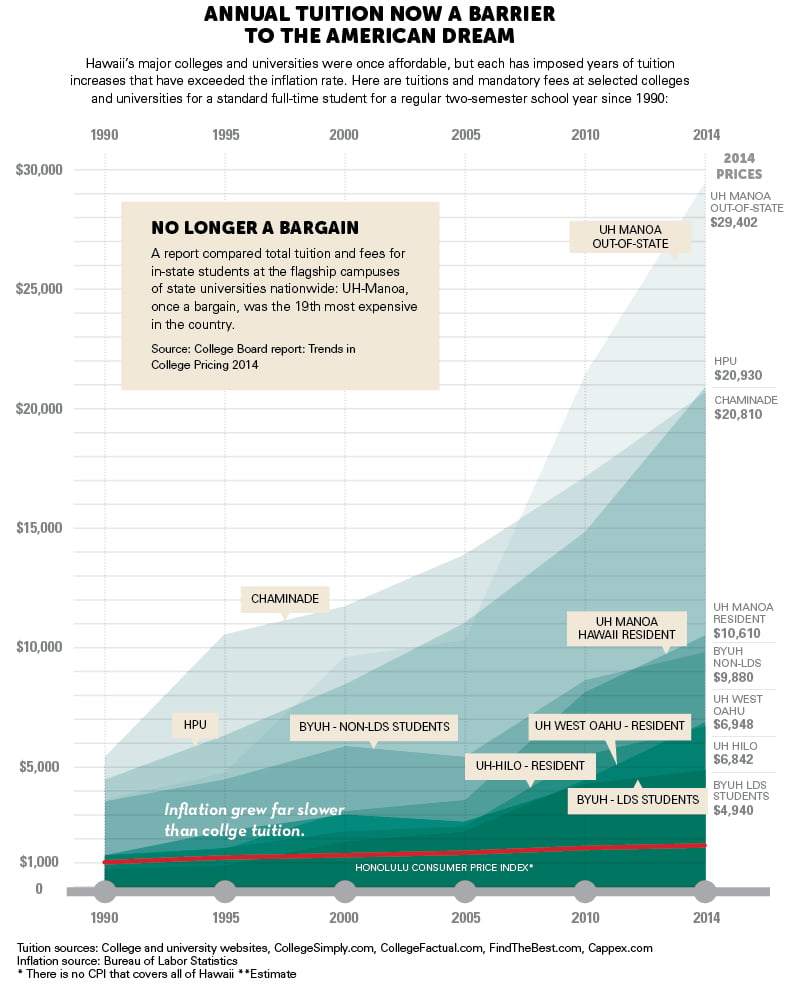

Not as Bad in Hawaii

In Hawaii, the numbers are a little better than in America as a whole – so far. The Institute for College Access and Success and other sources indicate that nearly half of local college graduates accumulate debt, but their average debt is only about two-thirds of the national average. Two big factors have helped hold down student debt in Hawaii for decades: strong state financial support for the UH system kept tuition among the lowest in the country and local private colleges were among the nation’s most affordable. But, in recent years, state support for UH has declined and tuition at UH and all the major local colleges and universities has risen at many times the inflation rate.

Brigham Young University-Hawaii increased its tuition for non-Mormon students by 46.4 percent from 2007 to 2012; Hawaii Pacific University increased its tuition by 12.7 percent and 12.5 percent during the past two years and Chaminade University’s tuition jumped 4.3 percent for 2014-15. Even so, all three universities remain bargains compared with most private colleges on the mainland.

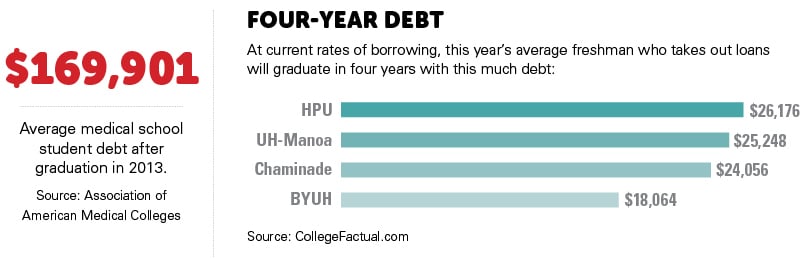

The website CollegeFactual.com says the average HPU freshman with loans will graduate in four years with $26,176 of debt, the highest average among the state’s main universities.

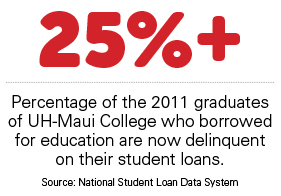

The UH system has nearly three times as many students as the major private colleges combined, so their debt is of special concern to Hawaii. The College Board says that, in recent years, UH has increased its tuition at one of the fastest rates in the nation. From 2006 to 2011, UH community colleges increased tuition 71.3 percent – more than any other state system – while tuition at UH’s four-year institutions doubled. A College Board report, Trends in College Pricing 2014, compared total tuition and fees for in-state students at the flagship campuses of the 50 state university systems nationwide: UH-Manoa, once a bargain, is now the 19th most expensive in the country.

Francisco Hernandez, former vice chancellor for students at UH-Manoa, is pessimistic about the future of higher education costs. “Private school tuition has been going up for a long time,” he says, “but it does not match the level public school tuition is going up, it’s going up so rapidly. Unfortunately there’s no end in sight.”

Francisco Hernandez, former vice chancellor for students at UH-Manoa, is pessimistic about the future of higher education costs. “Private school tuition has been going up for a long time,” he says, “but it does not match the level public school tuition is going up, it’s going up so rapidly. Unfortunately there’s no end in sight.”

Hernandez says tuition is raised to meet rising costs: UH must pay competitive salaries to professors or lose them to mainland schools. There is also a need to fix aging facilities and meet the demand for new and better ones, all while UH has gotten less money from the state Legislature in recent years. “As the tuition goes up, states see it as an opportunity to shift even more of the costs to the students and they provide less and less. That’s really a national phenomenon,” he says.

From 2007 to 2012, state funding for the UH system declined by 27.8 percent, compared with a national average of 23 percent, according to a report by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Only Louisiana had a bigger percentage cut.

Hernandez estimates that, during the 2013–2014 school year, UH-Manoa students borrowed more than $100 million to attend school. “I would describe the loan situation as a looming crisis because the indebtedness is too high and getting higher.”

A recent survey by the Hawaii Educational Policy Center shows how rising tuition discourages many students from completing their degrees locally. The survey found 15 percent of UH-Manoa students are thinking about transferring to schools outside of Hawaii for financial reasons, while another 10 percent admit they would not be attending college at all without their waiver or scholarship. One student said, “I am getting financial aid to cover 100 percent of classes and books. However, the cost of living is very high, so it makes me feel that I have no time to sit around and study, that I should be putting in more time at work to bring home more money to pay the bills.”

A separate study by the Institutional Research and Analysis Office at UH found that, among those who dropped out without graduating between the spring and fall semesters of 2012, the top six reasons were all forms of financial difficulties.

Despite its declining support, the state government is still the most significant sponsor of the UH system and one of the strongest supporters of higher education in the nation. A report by the College Board, Trends in College Pricing 2014, says state funding per full-time equivalent student is about $12,500 a year at UH – the third highest rate in the country. The national average among the states is $7,072 a year.

Market Forces

Some economists attribute much of the skyrocketing increase in tuition nationwide to market factors, especially the availability of student loans and pressure for competitive advantage. A few observers have even compared rising tuition at private colleges to the housing bubble of the mid-2000s because of the many similarities: government support and readily available loans from the private sector, plus alluring interest rates and a nearly universal perception that the investment will pay off handsomely. In fact, some economists argue, there’s little market pressure incentivizing colleges to keep prices down.

“It’s a product of what people are willing to do. If people weren’t willing to pay these prices, then these colleges would go out of business,” says Dan Peters, a homegrown UH-Manoa graduate and senior VP at WealthBridge Inc., a wealth management company.

Why do some students borrow tens of thousands of dollars to get a degree? “A big part of it is the American Dream,” Peters says. “A lot of people feel like, if you get into a college, that’s the pinnacle, you’ve made it. But they don’t realize that now they have to pay for it. Getting into college is great, but at the end of the day a lot of these universities are businesses: If they know they’re going to make money out of you, they’ll let you in.”

The universities’ higher costs come in many forms, including new facilities such as UH-Manoa’s new recreation center and HPU’s Aloha Tower renovation. Some observers blame higher administrative costs. A report by the Delta Cost Project shows that, from 1990 to 2012, the ratio of full-time faculty to administrators changed profoundly at universities nationwide. Now there are 2.5 instructors for every non-faculty staff member, down by 40 percent. Faculty salaries have largely remained flat nationwide, after accounting for inflation, but not so salaries for football coaches: As in many states, UH’s football coach, Norm Chow, is Hawaii’s best-paid public employee, with a salary of more than half a million dollars a year.

Good Debt to Have?

Federal Education Secretary Arne Duncan believes the price of higher education is still worth it. “Obviously, if you have no debt, that’s maybe the best situation,” Duncan said in 2012, “but this is not bad debt to have. In fact, it’s very good debt to have.”

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco estimates that, if college lasts four years and costs $21,200 a year – about average – a B.A. or B.S. graduate who borrowed to pay for all of it would break even with a high school graduate at age 38. “Earning a degree clearly remains a good investment for most young people,” the bank concludes. But financing that degree with loans leads you into a world of complex and arbitrary rules that are difficult to understand and treacherous to navigate. Unlike most forms of debt, including debt from gambling, student loans are nearly impossible to discharge through bankruptcy. “It’s very complicated and the chances are very slim,” says Wendy Burkholder, executive director of local nonprofit Consumer Credit Counseling Service. “Student loans, taxes and child support are debt that you never ever get out from under until you face the issue and deal with it.”

But financing that degree with loans leads you into a world of complex and arbitrary rules that are difficult to understand and treacherous to navigate. Unlike most forms of debt, including debt from gambling, student loans are nearly impossible to discharge through bankruptcy. “It’s very complicated and the chances are very slim,” says Wendy Burkholder, executive director of local nonprofit Consumer Credit Counseling Service. “Student loans, taxes and child support are debt that you never ever get out from under until you face the issue and deal with it.”

The federal government, for instance, has a lot of power to collect its student loans from you. “They can also garnish your wages without going to court, or through the same steps every other creditor has to do. They can just take about 15 percent of your net pay,” Burkholder says.

Student loans are a huge political issue, and the most disadvantaged participants in that debate are the students and their parents – a group that has no lobby in Washington. Representatives of the student loan industry, however, do have lobbyists and are not afraid to flex their muscles. The nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics, for instance, reports that the largest private loan lender, Sallie Mae, donated $2.8 million to politicians in 2013 to further its interests.

For-profit colleges, financed almost entirely from tuition, are also vocal advocates for the status quo. The Chronicle of Higher Education points out their rise is partially due to their equal participation in the student-loan industry, as student loans are usually not calibrated for the higher risk that comes with their degrees and institutions. While only 10 percent of all students attend them, for-profit colleges and universities are responsible for more than a quarter of federal student loans and almost a half of all defaults. Data from the Center for American Progress suggests that students in for-profit colleges – on average, they are of lower socioeconomic status than students at nonprofit private colleges and public universities – are the primary consumers of risky private loans.

Another ingredient in the student-debt cocktail is that student loans are not governed by the same protections provided to other forms of credit by the federal Truth in Lending Act. Nationally, private lenders and for-profit colleges have been punished repeatedly for employing aggressive and misleading practices to get people to sign loan contracts.

Youthful Dreams

Young borrowers can also easily fall prey to upbeat college brochures, financial aid officials and loan officers who persuade them of the ease of paying back loans. Most people who take on student loans are in their late teens, hopeful, impressionable and eager to earn a degree. Few read or understand the legalese on the loan contracts, while too many have overly optimistic expectations of their earnings after college.

Delaney, the UH-Manoa student who graduated with a master’s degree in communicology (the new name for UH’s Speech Department), provides a glimpse into the thinking of college freshmen: “I’ve been told that, in America, if [I] want to get ahead in life, I have to have a college degree. I can’t afford a college degree? What are my options? Oh, there’s financial aid available. Okay, I’ll sign up.”

But he now realizes that reality is at odds with youthful hopes. “There’s not a whole lot of jobs lined up for a graduate with my degree, even though it’s a master’s,” he says. “And just knowing that I’m going to be paying $600 to $800 a month on student loans alone – that doesn’t include car payments, house payments, food, any of those sorts of things – it seems insurmountable.”

But he now realizes that reality is at odds with youthful hopes. “There’s not a whole lot of jobs lined up for a graduate with my degree, even though it’s a master’s,” he says. “And just knowing that I’m going to be paying $600 to $800 a month on student loans alone – that doesn’t include car payments, house payments, food, any of those sorts of things – it seems insurmountable.”

In fact, Delaney may be underestimating his loan payments. The online calculator at FinAid.org suggests he would normally have to pay $920.64 a month, based on his cohort’s 6.8 percent interest rate on a Stafford loan over the target period of 10 years. For that kind of debt repayment, the site recommends an annual salary of at least $110,000, so the debtor could spend 10 percent of his gross income on repayment. However, a typical entry-level job in public relations, for which Delaney might qualify, usually pays about $40,000 a year.

The student-loan system “is a very unsustainable and inefficient model,” he says. “It’s almost insane to keep perpetuating it. … And it’s not a matter of ‘if’ the student loan bubble pops, it’s a matter of ‘when.’ ”

“It just seems like a racket to me, so I’m going to test and see what happens if I don’t pay,” Delaney says. “I’m not sure where that would get me, but I don’t have any assets, I don’t have a house, I don’t own anything: There’s nothing to my name, so I’m not sure what they would try to do if I don’t pay.”

If you try to refuse to pay, the lenders will still get their money and they will tack on extra late fees and interest, plus a big cut for collection agencies, attorneys’ fees and court costs.

Burkholder cautions against defiance and refusing to pay, because she says there are better alternatives built into federal law and regulations. “That’s the part that’s heart-breaking as a counselor, because you have options in the beginning,” she says. “If you can’t make your payment, say so!”

Burkholder has 25 years of experience at CCCS, Hawaii’s only nonprofit credit counseling service, and she says debtors should not procrastinate when they are struggling to pay. Too many “bury their heads in the sand and hope it goes away. It doesn’t!”

But beware of companies offering to help. “The rougher the ocean, the greater the number of predators,” Burkholder says. She offers a couple of practical suggestions for those considering credit counseling. First, any firm ought to be verified with the Better Business Bureau and, if it doesn’t have any history, it probably shouldn’t be trusted. Second, people should use common sense. “If it sounds too good to be true,” it is, says Burkholder. When someone says: “ ‘We’re going to make your debt go away in 30 days and we have a 100 percent guarantee’ – your little alarm bell should be going off.”

But beware of companies offering to help. “The rougher the ocean, the greater the number of predators,” Burkholder says. She offers a couple of practical suggestions for those considering credit counseling. First, any firm ought to be verified with the Better Business Bureau and, if it doesn’t have any history, it probably shouldn’t be trusted. Second, people should use common sense. “If it sounds too good to be true,” it is, says Burkholder. When someone says: “ ‘We’re going to make your debt go away in 30 days and we have a 100 percent guarantee’ – your little alarm bell should be going off.”

One possible solution to the crisis of student debt has been used in Australia for years, and is just now starting to be implemented in Oregon and Illinois. State Rep. Gene Ward thinks Hawaii should study how the system works in those states. The Republican, who represents Hawaii Kai and Kalama Valley, introduced similar legislation in the 2013 session at the Capitol. HB 1516 – also known as “Pay It Forward, Pay It Back” – would have created a state fund to pay for some or all of the tuition for interested Hawaii residents at public colleges. Students would sign contracts to have their wages garnished and pay off the debt after graduation, but no interest would be charged and payments would depend on income. The Hawaii bill was shelved while we await the results of Oregon’s and Illinois’ experiments with the system.

Whether that approach or something else is tried, radical change must happen, Ward says. “If we don’t get education reconceptualized, reengineered, refinanced, we’re in trouble.”

Every American generation has been better educated than its parents, until the past five years, he says. “The educational attainment of the parents is now superior to that of the children. And because we’re reversing history, are we also reversing some future opportunities – especially as China, Singapore, and Korea outmatch us in terms of test scores and numbers of Ph.D.s produced?”

Need Help?

If you are struggling to pay student loans, there are valuable resources online from these organizations:

• U.S. Department of Education, Federal Student Aid Office: studentaid.ed.gov/repay-loans/understand/plans

• The nonprofit American Student Assistance: www.asa.org/repay/options/default.aspx