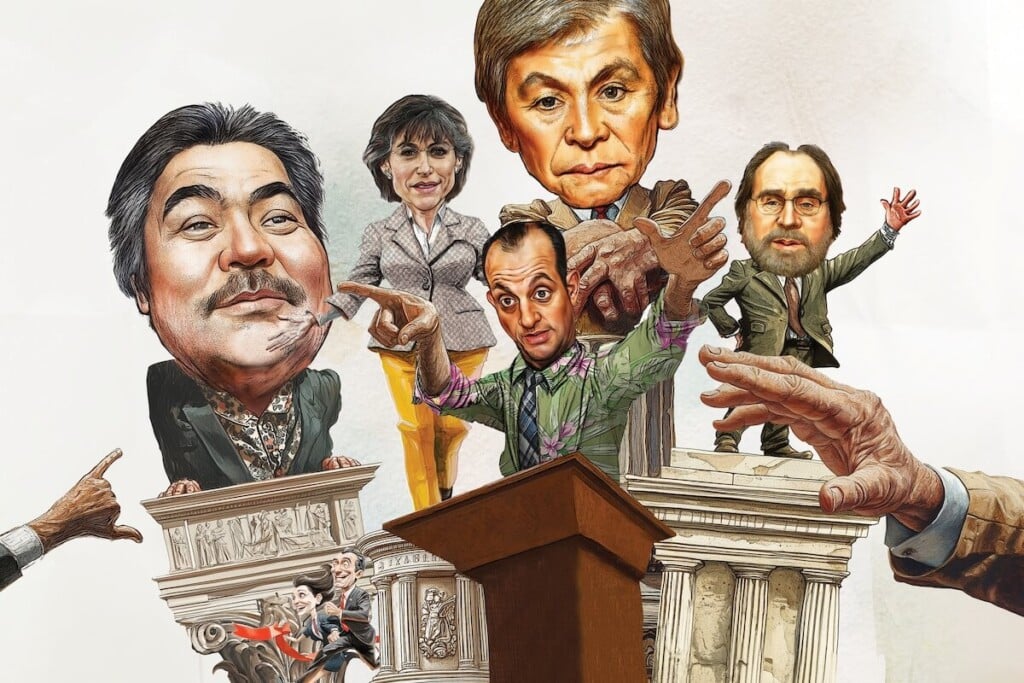

The Governor’s Choice: Hawai‘i’s Undemocratic Cycle of Influence and Power

The governor’s power to fill vacant seats in the state Legislature has been used at least 82 times. Some appointees then launched big political careers.

In the last three years, eight members of the state Legislature have been appointed by Gov. Josh Green. One representative, Mattias Kusch of Hawai‘i Island, has been appointed twice to his Hawai‘i Island seat without an election.

State law gives the governor the power of appointment and it has been used at least 82 times since 1964. Fifty-two people have been appointed to the House and 30 to the Senate. In 2025, one in eight members of the Hawai‘i state Legislature is the product of an appointment by a governor.

Some individuals appointed by the governor have enjoyed long, successful careers in politics and influenced public policy in unexpected ways. One appointee became governor, another gained election to the U.S. Congress. The longest-serving member of the state Legislature began his career with an appointment. The current president of the state Senate, a Democrat, was appointed in 2010 by then-Gov. Linda Lingle, a Republican.

Under the appointment system in place since 2007, the governor must fill a seat held by a Democrat with a Democrat and a seat held by a Republican with a Republican.

A key step in the process since 2007 calls for leaders of the state Democratic or Republican party – people chosen by the parties, not the voters – to submit a list of three finalists who have been party members for at least six months before the appointment. The governor chooses one of them to fill the vacant seat.

In the U.S., 25 states hold special elections to fill legislative vacancies; appointment processes in the other 25 states vary, according to Ballotpedia, a nonprofit and online encyclopedia of American politics. Only Hawai‘i has governors choose the appointees from short lists of party-selected candidates.

Ballotpedia also tracks the power of incumbency. In all 50 states, it says it analyzed election results for congressional, state executive, state legislative, state judicial and local offices. According to Ballotpedia, 95% of incumbents running nationwide were reelected in 2024, 94% in 2022 and 93% in 2020.

Among the 82 legislative appointees in Hawai‘i since 1964 that I could confirm, 14 did not run for their seats in the next election. But of those who did run, 49 won and 19 lost – a success rate of 72%.

Until this story, no public analysis of all appointments made by Hawai‘i’s governors to the Legislature has ever been done, according to several local political experts.

Some of these appointments were never recorded in official documents, even in the official legislative yearbooks compiled by the state House and Senate in 2014. No yearbooks have been publicly released since. To fill the gaps, I consulted press releases, news reports and documents from the Hawai‘i State Archives to peel away the extent of the appointments process.

Interviews with former governors, appointed officials and academic experts added to my understanding of this powerful, imperfect and ultimately undemocratic process.

Resignations, Deaths, Appointments and Reshuffles

Until 2007, the practice of making appointments to the Legislature was informed by a historical precedent established by the state’s second governor, John A. Burns.

Hawai‘i’s first elected governor, William Quinn, is not recorded as having made a single appointment. Burns, the first Democrat elected as governor, is recorded as making at least 12 appointments to the House and Senate.

Under Burns, the four reasons to make a legislative appointment emerged: (1) death; (2) resignation; (3) appointment to another office in state government; or (4) a political reshuffle as a result of another appointment.

Sen. Harry M. Field of Maui died of leukemia on May 23, 1964, leading to Burns’ first appointment. At that time, the governor’s only constraint was that the appointee needed to be a member of the same political party as the person who left that seat vacant. Field was a Democrat, so Burns picked a Democrat.

State Rep. David Trask, who was married to the governor’s sister and was a member of the influential Trask family, lived in the district and got the Senate seat, but lost his bid for reelection in 1966.

Trask’s appointment established a new practice known as the “political reshuffle.” Whenever a member of the state House, the Legislature’s lower chamber, vacates a seat to join the Senate, the governor needs to fill the subsequently vacant House seat. In Trask’s case, Tom Tagawa of the Maui County Board of Supervisors (the predecessor to the Maui County Council) was tapped by Burns to take Trask’s House seat.

Burns also appointed legislators to other state positions; at least two were appointed as Circuit Court judges and Burns filled their legislative vacancies. In 1967, when then-House Speaker Elmer Cravalho resigned to become chairman of the Board of Supervisors of Maui County, Burns filled his House seat. Cravalho was elected in 1969 as Maui’s first mayor.

Ariyoshi, Fasi and the Rise of an Outsider

Through their legislative appointments, governors demonstrated their political style. Gov. George Ariyoshi (1974-86), for instance, carried an independent streak and a penchant for inviting outsiders into the political process.

Ariyoshi’s most consequential appointment began as the last step in a political chain reaction that began with Honolulu Mayor Frank Fasi. Fasi had persuaded three Democratic members of the Honolulu City Council to become Republicans in 1985.

Then-Councilmember Patsy T. Mink was outraged and launched a recall campaign against the three new Republicans. All three lost their seats to Democrats in the recall election; two of those Democrats, Arnold Morgado and Donna Mercado Kim, resigned their seats in the State House to serve on the City Council.

In those days, appointees simply had to be registered as members of the Democratic or Republican party – they did not have to be members of their party for at least six months, as is the current rule. James Kumagai, then chair of the state Democratic Party, who had a doctorate in engineering, was charged with generating lists of potential appointees to fill the House vacancies.

For Morgado’s House seat representing Pearl City, the three options were a longtime party worker; the son of an elected official; and a young outsider named David Ige, an electrical engineer with Hawaiian Telephone, now Hawaiian Telcom. But Ige was not a member of the Democratic Party.

“My appointment,” acknowledges Ige, now a former governor, “could not have been today under the rules and the law that have been passed since.”

On the Friday morning after Thanksgiving 1985, Ige received a phone call from a high school classmate who wanted to know whether he was interested in entering politics. Later that morning, he received a call from Kumagai, who went to Ige’s office and spent two hours talking about the Democratic Party’s influence on state politics.

The engineer, then 28, expressed interest in the appointment. A few hours after Kumagai left his office, Ige received a call. “Dr. Kumagai called me back and said that the governor wanted to meet me.”

Ige’s office at the corner of Alakea and Beretania streets in downtown Honolulu was within walking distance of Washington Place, the governor’s residence. A meeting was set for 3:45 p.m. Kumagai met Ige before the meeting, and on his way over to the governor’s residence, Ige filled out his Democratic Party membership card. At the meeting, Ariyoshi offered Ige the House seat.

Ige told Ariyoshi he needed to consult with his boss. It was now late afternoon on that fateful Friday. Ige called his boss and told him what happened. Several minutes later, he was on a phone call with several layers of the company’s executive management, including his direct supervisor and two senior leaders of Hawaiian Telephone’s engineering unit.

Ige, who had been promoted to supervising engineer only a few months before, was told to not accept the appointment. “So I called Jimmy Kumagai back and said that I really appreciated the governor’s consideration, but I just talked to my boss and there’s too much going on.” Kumagai said he understood and asked Ige to wait a bit.

Ten minutes later, Ige received a phone call from Charles Crain, president of Hawaiian Telephone. It was his first conversation ever with Crain, and he recalls Crain’s assurance: “If the governor wants to do this – [and] if you’re interested – then you’ll have the full support of the company.”

In December 1985, Ariyoshi appointed David Ige, 28, and Jake Manegdeg, 55, to the state House. While Manegdeg was defeated when he ran to keep his seat in 1988, Ige won his election and two more House elections after that. Six years after his initial appointment, he was elected to the state Senate, succeeding Eloise Tungpalan, who had been appointed by Gov. John Waihe‘e in 1987. In 2014, then-Sen. Ige was elected governor – 29 years after he was appointed by George Ariyoshi.

The times, Ige knows, have changed. “It’s a very different process now. And clearly the parties are front-and-center on [building] the short list.”

Curtailment of the Governor’s Powers

Governors were free to pick anyone who was willing to sign a party membership card until the Bev Harbin incident of 2005. Until that point, every governor who had made an appointment had been a Democrat. Lingle was the first Republican to wield that power.

Harbin was Lingle’s pick for a House seat left vacant by a Republican’s resignation. She was later found to owe $123,000 in state taxes, a scandal that embarrassed the governor. “Had this information been disclosed during the interview process, Ms. Harbin would not have been appointed,” Lingle’s chief of staff wrote in a statement.

In early 2006, the Democratic members of the Legislature launched an assault against Lingle. “We’ve seen in the past that some appointments have been made [after] really listening to the community and some appointments have been made ignoring the wishes of the community,” state Rep. Brian Schatz told KHNL in February 2006.

Lingle defended the same process that had benefited Democratic governors Burns, Ariyoshi, Waihe‘e and Cayetano. “The process we have in place is a good one,” Lingle said then. “I don’t think we should re-create a process just for me whereas every previous governor had some latitude, and I think that should continue.”

The Legislature ignored Lingle’s reasoning. In the 2007 session, state Sen. Gary Hooser introduced Senate Bill 1063 to change the process. Under the proposed law, the governor would be required to fill any vacancy in the Legislature by selecting from a list of three names selected by “the political party of the prior incumbent.” The bill also required that the applicant be a member of the party for “at least six months prior to the appointment.”

Among those individuals who passed the Senate bill out of the House Judiciary Committee was then-state Rep. Josh Green. The bill speedily passed both bodies, arriving on the governor’s desk on April 12, 2007.

Lingle issued a veto message on April 25. “This bill places the ability for determining who may be appointed by the governor with the political party leadership of the vacating office holder. This is in spite of the fact that these individuals are not elected by the public and, as such, are not accountable to them,” wrote Lingle.

She said another consequence was how the pool of potential applicants would be severely narrowed by the discretion of either the Republican or Democratic party. Such conditions would “unreasonably restrict the pool of potential candidates as the majority of people who personally and philosophically associate themselves with a political party and vote along party lines may not meet this requirement.”

On May 1, more than two-thirds of both legislative chambers overrode the governor’s veto and the bill became law. Among those legislators voting to override was then-Sen. David Ige, a beneficiary of the old appointment rules that paved the way for his political career and eventual rise to the governor’s office.

As for Harbin, she was defeated for reelection in 2006 by a legislative aide named Karl Rhoads, a prior applicant for the appointment who was passed over by Lingle.

A New Role for Hawai‘i’s Political Parties

Since 2007, 33 appointments have been made by four governors, who picked from a list of three names selected under a process facilitated by the party of the seat’s prior incumbent. To date, all appointments have been to seats vacated by Democrats. As a result, the Democratic Party has managed the process for soliciting applicants to fill vacancies.

Following an interview process managed by the party’s county chair, three applicants are selected as finalists for the governor’s selection. Even under these circumstances, governors enjoy much latitude. Former Gov. Neil Abercrombie called on his decades of experience in various local political circles to inform his decisions. “Hawai‘i’s still not much bigger than a village.”

When he appointed Derek Kawakami to the House in 2011, Abercrombie recalled his history working with leaders from Kaua‘i, like Kawakami’s Aunt Bertha (appointed following the death of her husband, the speaker of the House, in 1987). Even with Kawakami’s own track record as a member of the Kaua‘i County Council, “his political legacy made him humble,” Abercrombie says.

In Abercrombie’s eyes, each of his appointments were based on standards of “character, temperament and background.” As shown by the Harbin incident, a poor appointment could be a political liability for the governor. Since then, the party has done much of the vetting of candidates for the governor.

Does the Status Quo Work?

The 2007 law granted more power to state party leaders – especially Democrats. “The Democratic Party in Hawai‘i used to be a powerful entity. Today, this is one of the things that still gives it power,” observes UH professor Colin Moore.

In fact, Moore says, “it makes the party more powerful.”

“They’re clearly the biggest beneficiary of the current system because it keeps them relevant and it’s one of their most significant current powers, but it’s not clear to me that it’s necessarily better than allowing the governor to pick anybody to fill the term, or anyone that’s a registered Democrat, like what Ariyoshi did with Ige.”

Quinn Yeargain, an associate professor of law at Michigan State University and the school’s 1855 Professor of the Law of Democracy, is one of the few experts in the United States to have researched the history of state legislative vacancies and temporary appointments in the U.S.

“There are reasons why governors aren’t the ideal appointing entity – given that the Legislature and governor are meant to check and balance each other. Having too many gubernatorial appointees in a legislature could be problematic,” Yeargain says. “But when the governor merely selects from a slate of candidates provided by the state or local party, a lot of those problems are ameliorated.”

The post-2007 rule places greater emphasis on a person’s ties to a political party.

Ige believes the process should be changed to broaden the pool of candidates.

“The current process really does exclude from consideration a lot of good community-minded people who would do a good job of serving. But because they’re not involved in the party, they don’t get considered,” he says.

Steps could be taken to permit more applicants through the state party system, such as removing barriers to a person’s eligibility for a vacant seat. Alternatively, a nonpartisan body could replace the role of the state parties – something akin to the reapportionment commission charged with redrawing legislative districts or the Judicial Selection Commission charged with overseeing judicial nominations.

For now, Yeargain says the “same-party appointment system is better than any alternative” – including letting anyone who signs a party card to be the appointee – and more cost-effective than financing a special election. “There are ways in which it can be improved, certainly, and it may look undesirable to an outside view, but the problems that it solves are too significant to ignore.”

Moore agrees, adding that “special elections for legislative seats are expensive and overly complicated.” Furthermore, one-time, off-cycle special elections can come with very low voter turnout, resulting in an undemocratic process for entirely different reasons.

“Because of the low turnout dynamic,” Yeargain explains, “the party that is more energized and enthusiastic about voting may be able to out-vote the other party in a special election, producing a result that may be incompatible with what district voters would otherwise want. In some ways, this can be worse than non-representation, because a district is represented by someone who has no claim to a mandate in casting ballots on behalf of their constituents.”

Where special election outcomes can be messy and divisive, a governor’s appointment may ironically come as a cleaner, simpler alternative to democracy’s natural acrimony.

Perhaps Hawai‘i is lucky. When there are vacancies, there are no campaigns, debates or elections. There is only the governor’s choice.