The Family’s Glass Ceiling

Women continue to face more obstacles than men when they aspire to lead their families’ businesses

small survey of women who work in their families’ businesses in Hawai‘i and California indicates they fare no better in securing leadership roles than women in the general business world.

One woman who had been passed over for a leadership position in her family’s business said, “How does this happen in our family and our business community? It isn’t fair, and I’m really frustrated by all of this.”

The survey was the third in a series of annual surveys of family businesses led by Honolulu-based Business Consulting Resources. The previous BCR surveys included just family businesses in Hawai‘i, but the latest includes California. It is based on in-depth interviews of women in 26 family-owned companies. Additional information for BCR’s survey report came from women in two focus groups.

The survey found that women were often passed over for leadership roles, including when leadership changed from one generation to the next, even though the women were arguably the most skilled and best educated candidates, and were considered right for the top job.

“One woman who participated in the focus group left the family business and did not return to it. She got a job outside and has no intention of ever returning to the family business,” says Jean Santos, a senior consultant and partner at BCR.

Leaving the family business altogether is uncommon, but what is common is the frustration suffered by aspiring and talented women who struggle to be taken seriously by their families, Santos says. Many times they settle for less than they want, but continue to help the family company.

“We had some who opted out and came back. I think it was a combination of things. They thought they needed to earn positions of responsibility in other companies outside of their family. And some said that they did that, and when they returned they (thought they) would be seen in a better light. But not always, unfortunately.”

Major pitfalls for women in family companies include two common categories, dubbed “Daddy’s Little Girl” and “Mommy’s Little Baby.”

“No matter who is wearing the CEO hat at the time a succession is to take place, whether that is Dad or Mom, both parents oftentimes have difficulties seeing their daughter as anything other than the sweetheart in pigtails on the swing,” says the BCR report.

“Many of the women interviewed reported that their fathers continue to view them as daddy’s little girl, long after they have proven their skills and capabilities, and taken on positions of increasing responsibility and authority with the family enterprise,” notes the report. In many cases, terms of endearment are used in front of employees and vendors.

The survey also found challenges for women who have risen to leadership roles in their families’ businesses. But interviewers also discovered that some women, especially from the second-generation in a family business, take the challenges in stride – even find them empowering and motivating.

Santos recalls what one woman said: “I’m going to take all these challenges and make them work for me and stick to my vision. … This is the family I’ve got, and this is the way they feel, and I’m going to find the good in that and work with it.”

Celine Casamina, an associate consultant at BCR, says people in the focus groups were asked for their advice for the next generation of family businesses.

“Many said, ‘Find support. Find your people, whether people in your family or a professional group. You’re not in this alone. It’s OK to need help or want to talk things through with a sounding board.’

“All of that has to be balanced out with the humility to listen to the older generation. It’s not just about being an innovator and a rebel. One of the most important things to say about a family business are the things that are passed down.”

“Get really clear on who you are and what you really want in the family business, and what is nonnegotiable for you in your life, and then go after it.”

Advice to women in family businesses from Jean Santos

Senior consultant and partner, Business Consulting Resources

Professor John Butler, faculty director of the Family Business Center of Hawai‘i at UH Mānoa’s Shidler College of Business, agreed that women often have a harder road to the top than men. But Butler says he definitely sees changes underway, with more women involved in managing family businesses. One reason, he says, is that families are smaller these days and therefore there are fewer sons to take over, plus women now often outnumber men in college graduate programs, including many business programs.

“At Shidler, 52% of the (undergraduate) business students are female,” Butler says. Of the graduate business students, 47% are female.

He has seen several Mainland-based surveys that show the number of women in leadership positions in family businesses has grown dramatically, and some of them even show women in these positions outnumbering men.

Women comprise half of the advisory board at Family Business Center of Hawai‘i, he says. “That’s some reflection of the degree to which women are present in management and ownership of the local firms.”

Nonetheless, Butler says, female leaders still have additional burdens, usually including child care and managing the household. “It’s tough work to be a senior executive in a firm, managing the costs, dealing with customers, trying to grow the firm. It’s a tough road, but all things being equal I think it’s tougher for females still. And there still is some bias.”

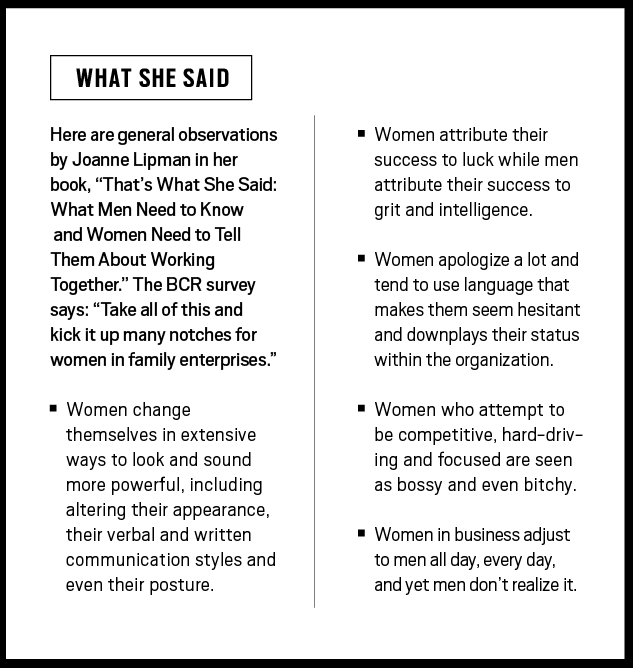

According to Joanne Lipman in her book, “That’s What She Said: What Men Need to Know and Women Need to Tell Them About Working Together,” social scientists have calculated that a woman must be two and a half times more competent than a man to be viewed as his equal. Furthermore, women in business are presumed to be incompetent until they prove themselves, while men are presumed to be competent, Lipman says.

The BCR report says that because of such perceptions, women in leadership make huge demands of themselves, especially regarding their skills, training and work ethic: “The imposter syndrome, the inability to believe that one’s success is deserved or has been legitimately achieved as a result of one’s own efforts or skills, is alive and well in family

The BCR report says that because of such perceptions, women in leadership make huge demands of themselves, especially regarding their skills, training and work ethic: “The imposter syndrome, the inability to believe that one’s success is deserved or has been legitimately achieved as a result of one’s own efforts or skills, is alive and well in family

business too.

“The women who participated in this research reported feeling compelled to become way overqualified for the positions they have in the family business, and for the positions that they want to take on as they progress. These women went back to school to earn advanced degrees, some of them worked outside the business in steadily increasing positions of power and control, and others sought the help of coaches and mentors, all to prove to themselves and their family members that not only did they have the skills and abilities to do the job, they were way overqualified for it.

“What’s even more startling,” the report adds, “is that many of the women in family enterprises have to defend their position, and what they know, to members of their own family!”

What surprised both Santos and Casamina was that, faced with such challenges, most women did not give up, or become angry or bitter. Frustrated, yes, but not defeated.

“Yes, they felt they had to go above and beyond the expectations of men,” Santos says, “but the recommendation we would make to any CEO is this isn’t just about women having to learn more about each position in the company to become a great CEO. That’s something every good leader should have when running a good organization. But that leads right into the expectation that women have to be better.”

What startles Santos is that even today, “We’re still having to deal with this, especially in the context of a family. I still can’t get over that. What also hit me is what can we do about it? How can we make a difference?”

Santos and Casamina say some of those efforts to make a difference include creating organizations like Inside Chief, the New York-based club for female executives, and Women in Family Business, an international organization that offers support and resources at womeninfamilybusiness.org.

“It might just be time for a Hawai‘i-based Inside Chief group for women in family businesses,” says the report.

Santos says the women who participated in the survey and focus groups want to stay connected and learn together, so BCR is planning to launch a platform that will provide those connections, including events and conferences for women in family businesses. An Instagram account may be the first iteration of such a platform.

Meanwhile, Santos has these words of advice:

“There’s a part of me that wants to say to women in family businesses, ‘Don’t beat yourself up.’ Get really clear on who you are and what you really want in the family business, and what is nonnegotiable for you in your life, and then go after it.

“And don’t look back.”

Here are profiles of three women finding success in their family businesses.

Managing a Bakery (and a Marriage) by Dividing the Duties and Talking

Colleen Paparelli has always known who the boss is in her family’s bakery business, The Patisserie. It’s her husband, Robert “Bob” Paparelli, and she’s perfectly fine with that.

She only takes umbrage when he steps onto her turf, which includes payroll, HR, IT, the website, advertising and the creative process of designing new logos, trademarks and packaging.

“I had no problem letting him be president,” says Paparelli, who has been her husband’s right-hand woman for 16 years at The Patisserie, a thriving bakery company with 150 wholesale clients in the state and plans to start shipping globally.

“He has more skills in the baking area than me. He oversees everything in the bakery.”

But not in her arena.

“Throughout our lives working together, the hardest part is when he comes in and tries to overrule a decision I made.” Her response, she says, is, “Wait a minute, this is my area.”

Over their years together, the Paparellis have learned to handle their conflicts by discussing the issues and solving big problems together. Her decision-making process is based on assembling as many facts as possible, weighing them all and coming to a conclusion.

“It’s just a matter of forcing him to sit down. Having an openness and discussion about things really prevents a lot of problems.”

The small everyday things are relatively easy. “Any big decision we wait until we both agree and we’re in unity. If we don’t, that creates stress in our relationship,” she says.

Colleen Paparelli runs The Patisserie with her husband. “Any big decision we wait until we both agree and we’re in unity,” she says. | Photo:Tommy Shih

When they do disagree, and she says no to something big, the situation doesn’t always end there. She admits she can be persuaded by a good argument or changing circumstances.

“My no today may be a yes in six months,” she tells him. “I can’t give you a reason. It’s just no today. But come back to me in three months or six months or a year. So we shelve it and revisit it later.”

The Paparellis have been married for 38 years and worked together in a bakery business in Arizona. He came to Hawai‘i first as a troubleshooter for another bakery, but soon called her in Arizona.

“Put the house on the market,” he said, “this is where we were meant to be.”

“Neither of us had ever even vacationed in Hawai‘i,” she says, “but the theme at our wedding was Asian food, rainbows and anthurium.”

Once settled in, they realized they wanted their own bakery. Bob had met Rolf Winkler, the business partner of Michel Martin of Michel’s restaurant fame. Winkler and Martin had launched The Patisserie, but a year later sold it to the Paparellis. Her official title now is VP and secretary of the corporation.

“It has taken years to adapt,” she says of learning to work together in a business. “I think the best key I discovered – but it took me 10 or 12 years of marriage – we learned to sit down regularly, maybe every few years, or maybe more often, and discuss the future” and find a way that works for both of them.

The company is poised for growth. The Paparellis have added automation and have plenty of unused production space, and they’re getting an international food safety certification this year so they can ship anywhere in the world.

“What really helped me was to remember that men and women are so different, whether people want to acknowledge it or not – how we think and process – and know and recognize what our strengths and gifts are.

“We’ve come a long way and we’ve learned a lot. It’s fun, but it takes time.”

An Outside Consultant Can Help Resolve Family Power Struggles

Holly Harding built a multimillion-dollar business with her husband and is now building a second. Their complementary strengths mean they work together well, but at times they have still needed outside help to iron out power issues.

“There have been moments when it has been very challenging between the two of us. But everything we’ve been through over the years and collecting the skills we have, we’ve gotten through the power struggles,” she says.

“In a situation where you have a business, and you have members of your family working with you, you’re going to have troubles. We have worked with everyone from consultants to a family therapist. And one of the most valuable tools you can do is have that (third) party objectively come up with a solution.”

During their successful businesses and 19-year marriage, Holly and Ashley Harding have also learned better how each

other communicates.

“I would say I’ve never been one to feel that being female has been a hindrance in business,” Holly says. “I’ve never felt that at all. We know our roles and know what we’re good at.”

She says they both like to be in charge, but in their first business, Bubble Shack, he gravitated toward the role of CEO because he focused on operations, personnel and finances.

“I have a different set of talents and that has been the key to making it work,” she says. “I have a talent in marketing and sales and product development – the strategic and creative side. Having a separate set of duties and obligations was key. Over the years we have learned to be able to take the overlap and make it work.

Holly Harding has run two businesses with her husband. “We know our roles and know what we’re good at,” she says. | Photo: Tommy Shih

The Hardings first shared a passion for music. They met at the Eastman School of Music in New York where both trained as classical musicians. He played saxophone and she clarinet and they eventually made a living with their music in Boston.

Fifteen years ago they moved to Hawai‘i and joined the Honolulu Symphony. Quickly, they realized their two salaries would not be enough to live comfortably in expensive Hawai‘i.

“In Boston I had started a music entertainment agency and was booking myself and other musicians for all sorts of gigs. But my husband had this obsession with soap so we started making soap in our kitchen, learning how to do it and stirring it up on the stove. And people liked it.”

Eventually the couple turned a $25 investment into a multimillion-dollar business, Bubble Shack Hawaii. But after years of working seven days a week, 12 hours a day, they wanted more time to focus on themselves and their health.

They sold the business and Holly studied health and nutrition online at the Institute for Integrative Nutrition in New York. That evolved into O‘o Hawaii, a new business named after the native Hawaiian bird. In this business, she became CEO –or as she calls it – the “leader of the flock.” The company launched last year and by the end of 2019 she expects O‘o products to be in 150 stores across the U.S. and in Tokyo and Okinawa.

While he’s not O‘o’s CEO, her husband fills many of the same roles as he did with Bubble Shack – overseeing finances, manufacturing, contracts and the business side – while she designs and creates products.

“His innate nature is to be the leader. That’s part of his DNA,” she says. “He’s also a very strong, capable CEO-type and a dragon in the Chinese calendar. I had to slay the dragon (to be CEO),” she says.

“I would say we both tend to like the spotlight because of the onstage performing nature of our lives. So there can always be a little bit of the struggle to maintain a balanced persona within that spotlight. We have to allow each other to both have that space in the arena.”

She Had to Work Her Way into the Family Business

Tiffany Richardson was born the year her parents founded Current Affairs, a company that has created, designed and produced special events for 35 years. Last year she became Current Affairs’ president and a partner in its parent company, International Catering Concepts.

But Richardson’s rise to the top was anything but simple or easy. When she came home after college, with a major in public relations and a minor in business management, she wondered aloud what she was going to do.

“No, no, no. You don’t work for us,” she remembers her parents telling her. “They said, ‘This never was the vision, for you and your sister to take over.’ ”

They wanted her to learn the business world elsewhere.

Richardson did, spending six years working in marketing, often as an assistant in other companies. Then she approached her parents again.

“I would like to apply for a position at Current Affairs,” she told them.

“And they said, ‘What are you going to bring to the table?’

“Let’s meet,” she replied, “and I’ll provide you with a resume.”

She did, landed a job as her father’s sales assistant, and began learning the business from the ground up. “I don’t want to be the silver spoon person or get special treatment. I wanted to get down and dirty and see how my parents built this.”

In accordance with her wishes, her father never referred to her as his daughter when they met clients. She was introduced simply as Tiffany, and for years many clients had no idea she was family, Richardson says.

That respect and professionalism continues to be a watchword of the company, and for the way it treats employees, customers and family members, she says. It’s also how Richardson conducts herself, although she sees the company’s 15 employees as family, with a chatty and personal style of her own.

Tiffany Richardson is gradually taking over the family businesses from her parents. | Photo: Tommy Shih

When she first joined the company, she says, “I was more one foot in and one foot out, trying to figure out where I’m going.”

That process evolved as she fell in love with her parents’ creation and began to have a vision of her own on how to grow the company, she says. That process meant regular conferences with her parents, and a constant reassessment of the company’s future.

“I said, ‘What is the vision? Where are we going with the business? I’d like to know what I’m getting into before signing on the dotted line.’ I really wanted to get into their mindset. They said, ‘What are your suggestions?’

“I said, ‘I believe we could grow, but the way is to hire more sales associates.’ On the sales team it was just my father and me, and two event managers. And they said, ‘OK, we’ll figure it out.’ Once I was able to get someone else on board and train and groom them for the job, I became sales manager. From there I was able to start to develop a team even more and look at our projections and could we afford another one. Those were the road maps for me.

“I am now seven years with the company,” says the entrepreneur, who spends much of her waking hours in the business while also raising children. Plus, there’s now a second family business, EventAccents, a specialty décor rental company.

“It’s a Millennial and a Boomer, with a myriad of complexities that those two worldviews create.”

Tiffany Richardson, President and partner, Current Affairs

and EventAccents, talking about working with her father

Tiffany and her parents, Philip and Violet Richardson, continue to work together although the parents are slowly phasing themselves out. Her mother wants to leave in a year to start an allied business of her own, much like the two businesses run by Tiffany’s sister, Chantelle Williams. Chantelle’s businesses involve creating floral displays, often for special events.

Her father plans to ease out in the next five years.

The transitions have strengthened Richardson’s ability to lead. Her father suffered a serious accident in the past year, and she took the reins fully and led the company through those difficult times until he recovered.

He now treats her as a highly skilled and competent leader.

“It’s not gender for us,” she says. “It’s a Millennial and a Boomer, with a myriad of complexities that those two worldviews create. It’s different styles rather than different genders. One thing that he reiterates is the deep level of caregiving of the staff (that she does) and that he didn’t do. And he points that out in front of the team, and that has added a lot of dimension to me as the leader.”

As gratifying as that is, Richardson admits the responsibilities of leadership still weigh heavily.

“It’s been exciting, exhilarating, inspiring and terrifying. It’s not like I can punch out or find another job. This is our family business and those who work for us are our family as well. It’s a core value. There’s just a lot more than getting the work done.”

Women in Family Business Event

Join Hawaii Business Magazine and Presenting Sponsor Bank of Hawaii for a discussion on how women in family businesses deal with the many challenges they face.

The panelists include:

- Kaleialoha K. Cadinha-Pua‘a of Cadinha & Co.

- LiAnne Coon Driessen of Trilogy Excursions

- Kaleo Schneider of Buzz’s Original Steak House

- Justin Levinson of William S. Richardson School of Law

- Jean Santos of Business Consulting Resources.

The event is Thursday, Nov. 14 at 11:30 at the YWCA on Richards Street in downtown Honolulu.

Register at Hawaiibusiness.com/FAMILYBIZ19