The Doctor is Not In

Hawaii is 500 doctors short. Here’s what the UH medical school is doing to fix the huge deficit, especially on the neighbor islands.

The Neighbor Islands count success in single digits these days: Two new doctors on Kauai over the last few years. Two on Maui. Six or seven on Hawaii Island. Two on Lanai, though both later moved back to the Mainland. None on Molokai.

“Part of the solution is working together to find smarter ways to deliver care.” -Jerris Hedges, Dean of the John A. Burns School of Medicine.

“We’ve been rotating folks to Hilo for a long time and that’s mostly how a lot of the new family-medicine physicians get to Hilo. Over the last 10 years we’ve placed six or seven,” says Lee Buenconsejo-Lum, head of the residency program at UH’s John A. Burns School of Medicine, which places new doctors in three-year residencies statewide after they graduate.

“It’s a fairly high percentage that have ended up on the Neighbor Islands,” says Buenconsejo-Lum. “We’ve tried to make the Neighbor Island experience available as much as possible to introduce them to rural medicine and the community. It’s important to provide that residency rotation, otherwise you’ll never get anyone to the Neighbor Islands.”

Hawaii’s physician shortage, especially on the Neighbor Islands, is dire. Patients sometimes wait four and five months on the Neighbor Islands for both primary care and specialist appointments. There’s now an estimated shortage of 500 physicians throughout the state, but if you look more deeply into statistics using a national formula, it’s more like 700, says Dr. Kelley Withy, director of the medical school’s Area Health Education Center.It’s going to get worse, Withy says.

“In 2019, a whole bunch of changes take effect that will cut Medicare reimbursements for physicians who don’t have electronic records. We have a lot of senior (physicians) who are going to quit. Right now there are over 600 physicians (in Hawaii) who are 65 years old or older.

“It costs $40,000 to change to electronic medical records. Some hospitals like Hawaii Pacific Health and Queen’s will help you. But, if you’re a solo practitioner, you’re looking at a lot of expense and training and frustration. So we have that to contend with.”

That’s not all.

“We need to train more, but we’re pretty much maxed out on Oahu in terms of space,” says Withy. “Medical training is very labor intensive. It has to be supervised. The fact that we don’t have enough doctors makes it harder to train new ones; we need doctors to train doctors. But since we don’t have enough, it’s hard for them to train new doctors because they’re so busy.

“And don’t get me started on the paperwork these days.”

In 2016, with the addition of new doctors in Hawaii, offset by retirements and moves away from the Islands, “We gained 100 doctors,” Withy says. “The year earlier it was four. With 100 a year, that would get us to where we want to be by 2025. But I don’t think that’s going to happen.”

Dean Jerris Hedges says JABSOM is focused on training, recruitment and retention of physicians, and collaborating with other health disciplines to build healthcare teams.

“It’s important to provide that residency rotation, otherwise you’ll never get anyone to the neighbor islands.” -Lee Buenconsejo-Lum, Head of Residency Program at JABSOM.

“Part of the solution is working together to find smarter ways to deliver care,” says Hedges. “We work closely with UH’s schools of Nursing, Social Work and Public Health on new models in how we train together so our graduates will work better together.” There are many advantages to the collaborative approach: Some of the work commonly done by doctors in the past might be done by other healthcare providers instead; collaboration can reduce costs; and collaboration can produce a more holistic approach to treatment, and possibly better outcomes.

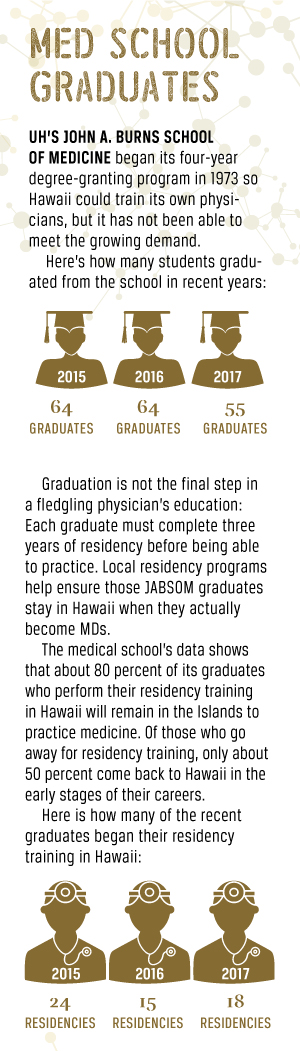

In March, the medical school was recognized nationally by U.S. News & World Report as 23rd in the nation for turning out the most primary care residents. (Residents are doctors in training after they graduate from medical school.) Primary care, the field with the biggest shortage, is defined as family medicine, pediatrics or internal medicine; 52 percent of JABSOM graduates choose primary care.

On Hawaii Island, which has the biggest shortage in family medicine, physicians like Melanie Arakaki are like gold.

On a recent Tuesday afternoon, the family practitioner and UH graduate was leaving her Hilo office for house calls with elderly home-bound patients. “If I see them face to face, then we can get home care for them – home health nursing and home health physical therapy,” she says. “We have to document it or insurance won’t pay for it.”

Because Hawaii Island lacks so many GPs and specialists, Arakaki treats everything. “We don’t have enough psychiatrists, so we do a lot of counseling, a lot of psych stuff. And a lot more cardiac care. I think we’re pretty good at it because we’ve had to do it because there’s no one to refer to,” she says.

“Gosh, we need everything. In Hilo, for example, there are two cardiologists for all of East Hawaii. There’s one urologist and one neurologist for the whole island; one permanent ear, nose and throat specialist for the whole island. There are just three orthopedic surgeons in Hilo, and four general surgeons – one of whom is retiring soon – two nephrologists and three gastroenterologists – two of whom are past retirement age; so we’re short on everything. Getting specialists here is a real problem. We don’t have an infectious disease specialist, an endocrinologist or a rheumatologist. A lot of our patients have to go to Oahu.

If we can’t get them in to see a specialist, insurance will pay a partial reimbursement for a flight.”

Arakaki grew up there and returned after her medical training and residency at the Burns School. With 5,000 patients in a joint practice with another physician, she is up by 4:30 each morning for a day that includes exercise, parenting two children as a single mom, and watching over a heavy caseload that brought 15 patients into her examination room this morning.

“Five out of the 15 asked if we’re taking new patients,” says Arakaki. “We had to change our answering machine because we were getting dozens of calls every day asking about that.”

“Five out of the 15 asked if we’re taking new patients,” says Arakaki. “We had to change our answering machine because we were getting dozens of calls every day asking about that.”

Coming home as a physician wasn’t her original plan, but it’s not surprising, because both her parents were nurses in the community, now retired, and she grew up around hospitals. She’s become a staunch supporter of residency rotations of medical students on Hawaii Island, and offers her time to mentor third-year students. Hilo Hospital supports student rotations by providing a house where students can live. There’s even funding to ship in students’ cars for their rotations. These rotations offer a small taste of what small town and rural medicine can offer.

“The really big draw is to have JABSOM get them here (for rotations),” says Arakaki. “And our Big Island residency program is going to be graduating our first class soon. The residency in Hilo is really, really new. It remains to be seen if they’ll stay, but that was the plan.”

Those of use who have come back to practice on the Big Island are from the island,” -Melanie Arakaki, Family Physician in Hilo

Arakaki’s personal mission includes bringing the message to students in middle and high schools about the medical needs in their community. She also does health fairs and shows up Sundays at 8 a.m. at Liliuokalani Gardens for the “Walk With a Doc” program that educates all comers on health issues.

“Those of us who have come back to practice on the Big Island are from the island,” she says. “The best shot of getting people here is to have people who are from here and have family here.”

Dean Hedges agrees: To grow a medical workforce, the school must train Hawaii’s own people – “People with a long-term commitment to Hawaii.”

“For the medical school, our target is 90 percent of the students we accept and matriculate are from Hawaii. Some have left to complete higher education before coming back, but they have a background in and a commitment to Hawaii.

“Often, the 10 percent we take who are not from Hawaii have some connection here, through a relative, or have family ties in the Pacific. That is an important part of our selection process.”

Hedges says the school does its best to select students from the Neighbor Islands to graduate physicians who will return to work there. To do that, the school is attempting to grow the Neighbor Island residency program that acquaints graduates with medicine in rural settings, plus strengthen and enlarge “faculty practice” on the Neighbor Islands. This provides a network of “teaching physicians” – offering support both for students and for the community.

“Right now we have around 200 practitioners who are part of the faculty practice and we’d like to grow that a bit,” says Hedges. “We want to fill niche areas – and, given the physician shortage, generally these practitioners are welcomed by the hospitals.”

Hedges says the state’s physician shortage reflects a U.S.-wide problem.

“We have grappled, as a nation, with the fragmentation of healthcare delivery and that continues to this day, even with the efforts of the Affordable Care Act,” he says.

Hedges notes Hawaii’s population is one of the oldest in the nation and so its healthcare providers must focus on “chronic disease management in helping our elders to age gracefully and maintain functionality.” That includes training students in new technology for distance monitoring, as well as building healthcare teams with the physician coordinating care and others carrying it out.

At Pali Momi Hospital in Waimalu on Oahu, none of this has been lost on January Andaya, who graduated from JABSOM last year and is almost finished with the first year of a three-year internship in family practice. After completing her residency, she will become a full-time, board-certified doctor, and she has plans to stay in Hawaii.

“It’s something I’ve thought about already,” Andaya says.

And Maui is calling. Literally.

“My uncle’s an architect on Maui and he said, ‘I can totally build you a clinic here. I’ll design it and there’s land right here!’ And then he’s telling me to specialize in geriatrics because of all the people there with needs in that age group.”

Andaya chuckles at her uncle’s phone calls, but takes them seriously.

“Next year is when we’ll start to have to think about what we want to do. I’ll be starting to interview next year. I’m definitely thinking of Maui.”

DISEASE FIGHTERS

The UH medical school has many research projects. Here are three that target stubborn global maladies: Heart Disease, Zika and HIV.

USING CANNABIS TO TREAT HEART DISEASE

Dr. Alexander Stokes

The leading cause of death worldwide is heart disease, killing about 17 million people a year. The cost in the U.S.: about $316 billion annually, says Dr. Alexander Stokes, an assistant professor of cell and molecular biology at the UH medical school.

That makes Stokes’ research on about 20 compounds in cannabis a potentially important contribution to health in Hawaii and around the globe.

“There are approximately 480 bioactive compounds in marijuana,” says Stokes. “I’m not interested in the psychoactive properties; what I would like to see us do is develop drugs based on the nonpsychoactive properties, not the ‘high’ marijuana compounds, so then anyone can take them without the psychoactive effects.”

For more than 50 years, people have treated diseases with cannabis, he says. It has already been proven effective in pain relief, stopping tremors from Parkinson’s and easing glaucoma.

“It’s an alternative to opioids,” says Stokes. “We have had such bad effects with opioids, we need alternatives. And this really offers a gateway into producing some really amazing drugs we know are eventually going to work.”

Stokes’ research centers on the ability of a mixture of cannabis compounds to slow continuing damage to the heart after an attack. “When you’re seeing some loss of function, it would be protective,” he says.

The process works through a pathway receptor called TRPV1, which is an entry route for calcium. Stokes showed that targeting TRPV1 with drugs slows damage to the heart muscle. TRPV1 can also be targeted by cannabis compounds, raising the possibility that the ‘natural pharmacy’ in the marijuana plant will provide new heart-failure therapies.

Stokes’ research also levels the playing field for small pharmaceutical companies who often can’t compete with the giants’ patented medications.

“The (marijuana) plant becomes the chemical factory,” he says. “You can patent the purification techniques but not the whole plant.” Smaller companies can test marijuana compounds, something that not only opens the field, but is less costly than testing purely with chemistry.

HUNTING ZIKA’S HIDING PLACE

Dr. Saguna Verma

Zika is a rising concern around the world, with 5,000 cases already reported in Florida and Texas, and tens of thousands more in U.S. territories. Transmission by mosquitos has not yet occurred in Hawaii, but the startling discovery that the virus can be transmitted sexually from men to their partners months after symptoms have disappeared has prompted new research at the medical school. Understanding the virus’ survival tactics may be crucial to effective treatment of the disease.

Even though a person’s immune system has cleared the virus from the blood, and symptoms such as fever are gone, the virus can be seen in seminal fluid in the testes for as long as 90 days. That means sexual partners will be at risk of infection during that time, says Dr. Saguna Verma, associate professor in the Department of Tropical Medicine, Medical Microbiology and Pharmacology. If the virus infects a pregnant woman, its devastating effects can include microcephaly, an otherwise rare birth defect in which a baby’s head is smaller than expected.

“The body has certain organs protected from the peripheral blood system,” explains Verma. “We have a blood-brain barrier and a blood-testes barrier that protect the brain and testes from outside dangers, including infection by micro-organisms. Most of the time this barrier works great, but some of these viruses are smarter and have learned ways to negotiate this barrier.

“We earlier showed that West Nile Virus has learned a way to pass through the blood-brain barrier and enter the brain, where it infects brain neurons and causes cell death. Similarly, we hypothesize that Zika has also learned a way to cross the blood-testes barrier and hides in the compartment of the testes called seminiferous tubules where the sperm are developed. This way, the virus can hide for long periods and infect the sperm. This infected sperm becomes a carrier that can go from one body to infect another.”

The challenge for researchers is enormous, Verma says: “To clear testis infection, we will need a medication that can kill the virus once it has crossed the blood-testes barrier. That means the drug has to be able to reach where the virus is hiding.”

The UH study is just one of many globally. “All these pieces from different studies will complete the puzzle and help develop guidelines for both disease management and prevention.”

Results could be far away simply because researchers have yet to pinpoint where the virus hides in the testes. Verma’s research specifically looks at Sertoli cells, which nurture the developing spermatozoa. “Can Sertoli cells be the reservoir of virus in the testes?” she asks. “Once we know the targets of Zika virus in the testes, we will be able to better tell if a drug can reach those cells and clear the virus.”

TRACKING HIV WITH “SHOCK AND KILL”

Dr. Lishomwa Ndhlovu

Dr. Lishomwa C. Ndhlovu lives with hope – hope that his research will help solve a puzzle that has eluded researchers for 40 years: How to totally kill the HIV virus in the body.

Globally, a single patient has been cured – with a bone marrow transplant that he received because he was also a leukemia patient. But researchers and doctors have been unable to replicate that breakthrough. Yet that one success offers hope that a total cure is possible, says Ndhlovu, an associate professor in the medical school’s Department of Tropical Medicine, Medical Microbiology and Pharmacology, and an investigator at the Hawaii Center for AIDS.

“Patients have to take their medications for life,” says Ndhlovu. “If they stop taking them, the virus will come back. The treatment is not curative right now.”

Researchers have been unable to find exactly where the virus hides in the body, though many believe it hides within the immune system itself. But he believes an important track is a new technique called “shock and kill.”

“We came up with the ‘shock’ approach. We know it’s sleeping, but we’ve identified some drugs to shock it out of its hiding place.

“Then the ‘kill’ approach is not only to wake it up, but to kill off the remaining virus with the immune system. The immune system is very powerful, but the virus has found a way to disable it. So, we’ve found restorative therapies to re-establish some of the pathways in the immune system that we hope will allow it to work better. They have been remarkably successful in the cancer field and we hope we can harness them for HIV.”

Ndhlovu’s primary goal is to find a cure, but he emphasizes that prevention is an integral part of the program that aims to reduce HIV cases in the state to zero. “Hawaii was the first state in the nation to introduce needle exchange. We’re very bold in dealing with epidemics.”

But people need to be more careful, he says.

“In the old days there was a lot of advertising to be careful to seek treatment. You don’t see that anymore. People have become complacent. But we keep getting new cases. And the number of people living with HIV is increasing because people are living longer, and that means there’s a larger population of people able to transmit the disease.”

More funding has been put into HIV research than any other infectious disease, Ndhlovu says. “We’ve had tremendous success in finding treatments that can at least let people live longer. We now have drugs that can kill the virus but not eradicate it.” Now there is increased talk and hope of a cure, he says.