Tension Over Tourism

Should Hawaii’s tourism czars focus on attracting more visitors or take a holistic view of tourism’s impact?

During good times, there is virtually nothing easier to sell than Hawaii.

If people have money and an itch to travel, all you need to do is remind them that Hawaii, with its sunny beaches, happy people and varied cultures, is more than ready for their visit.

But what about tough times? How do you sell Hawaii when it’s not enough for Hawaii to simply sell itself?

That’s the challenge currently facing the hotels, airlines and attractions that make up the state’s visitor industry. It also involves a potent mix of politics, money and the basic question of who is in charge of marketing Hawaii to the world.

In a recent special report commissioned by First Hawaiian Bank, Hawaii Pacific University professor Leroy Laney argued that while tourism is by far the dominant economic player in Hawaii’s economy (perhaps responsible for as much as 40 percent of the state’s GDP when multipliers are used), it receives far less focused attention than it deserves. In short, policymakers – like Hawaii’s general public – tend to take tourism for granted.

“It would help if there were more of a shared vision and coordination among state, county and individual agencies with regard to tourism policy and planning,” Laney argues.

That, says Mike McCartney, the recently installed head of the Hawaii Tourism Authority, is precisely what he and his agency are attempting to do. HTA was created in 1998 in response to the economic shocks created by the first Gulf War and the Japanese economic bubble and the continuing political unhappiness with the Hawaii Visitors Bureau (now the Hawaii Visitors and Convention Bureau).

HTA’s New Plan

The latest Hawaii Tourism Strategic Plan from HTA has five key “vision” points, which it says should guide tourism in Hawaii by 2015. By that time, HTA says, tourism will:

- Honor Hawaii’s people and heritage

- Value and perpetuate Hawaii’s natural and cultural resources

- Engender mutual respect among all stakeholders

- Support a viable and sustainable economy

- Provide a unique, memorable and enriching visitor experience.

What was needed, policymakers decided, was a Cabinet-level organization focused on the overall health and impact of the tourism industry, rather than a narrowly focused marketing organization like HVB, which was primarily responsive to the needs of hotels and airlines. Others in the visitor industry had withheld their support and dollars from HVB because they felt they were not being heard. That put greater pressure on the state and taxpayers to pay for HVB’s activities.

Ben Cayetano, who was governor at the time HTA was created, says it was an effort to manage tourism from a broader perspective – that is, taking into account tourism’s impact on such things as culture and the environment rather than simply how it affects hotels and airline traffic.

“Many politicians, including me, were unhappy,” Cayetano remembers. “It seemed because of tourism’s critical importance to the state’s economy, the Legislature found it difficult to deny HVB requests for more tourism marketing funds. Thus, there was little incentive for HVB to solicit more contributions from its dwindling membership. To compound matters, most legislators felt that, in fact, the state’s so-called oversight over how HVB used its funding was ineffective.”

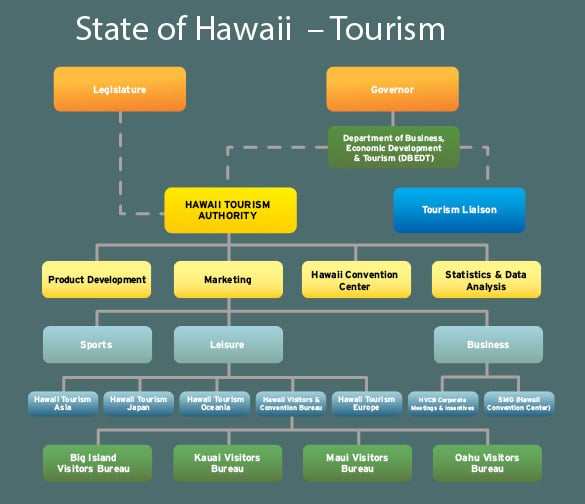

Source: Hawaii Tourism Authority

A deal was struck, and a critical part of it was that the Hawaii Tourism Authority would get a dedicated slice of the transient accommodations tax (commonly called the hotel tax) to fund its efforts. (From a high of around $90 million, HTA today receives around $70 million a year for its operations and marketing.) The industry concluded that if it was going to swallow the bitter pill of a hotel tax, much of the money should go to an agency dedicated to its interests.

Some argue that this new arrangement has done little other than shift control of tourism promotion from the hotels and airlines to politicians. It is true that those chosen to run HTA have been well-connected to the Democratic establishment in Hawaii.

That would include McCartney, formerly a state senator and head of Hawaii Public Television. But the personable McCartney says he is willing to be judged on his and HTA’s performances. A key shift, he says, is that HTA is now focused on what is best for Hawaii, not what works best for specific interests within the tourism industry.

“We are in the process of reinventing ourselves,” McCartney says. “The fundamental thing is the culture. If we don’t have the culture, we don’t have a product.”

That has led to a new “strategic plan” for tourism that reaches beyond the post-statehood concepts of visitor promotion to a vision that looks to the health of the state and its people, not just of the industry itself.

All that is well and good, but some in the industry worry that the grand vision will mean little if Hawaii fails to get enough people into airplanes and hotels (“butts in seats and heads in beds”).

“It’s lovely to have some Island-knowledge people involved (in the HTA),” says David Carey, president and chief executive officer of Outrigger Enterprises Group, Hawaii’s largest locally owned hotel and tourism company. “But there’s not enough folks with an actual stake in the industry on there.”

Seats will open on HTA’s board next year. Board members are nominated by the Legislature and appointed by the governor, representing public interests, the tourism industry, the counties and other parties. Carey hopes, he says, for more balance between those with a political or broader perspective, and those who know the industry and its needs.

Whether increased industry perspective is the cure-all is open to argument, Carey acknowledges. But he points out that HVCB marketing in North America, in which industry officials are directly involved, has been more successful than marketing contracted out in Japan, where direct industry involvement is minimal.

“It’s my belief that when industry partners are involved in the decision making, the results are better,” he says.

Call it a matter of “enlightened conflict,” Carey laughs.

In today’s climate, Carey says, the focus should be on maintaining the flow of people willing to come to Hawaii. “When business is down 20 percent to 25 percent, everybody has a problem,” he says.

“Cultural programs are wonderful, but they don’t bring people here. They might please them once they get here, but they don’t make people come.”

Who pays for tourism promotion?

The hotel tax is expected to generate nearly $211 million in 2009, down about 8 percent from 2008, according to the Department of Taxation. HTA will get around $72 million of that money. Some $30 million of the remainder will directly support the convention center and the rest goes mostly to the counties, with some for the state general fund.

He makes a comparison to Mexico, which recently launched a major promotion on the Mainland to offset the tourism slump it suffered from swine flu and other controversies. Mexico allocated close to $60 million for that promotion, not much less than the annual budget of HTA for all its efforts.

State Sen. Donna Mercado Kim, a frequent critic of HTA, contends the agency “is getting back on track. They’re holding their partners (HVCB and others) accountable for their marketing plans,” Kim says. Several years ago, she says, the agency “just took what the HVCB gave them. That wasn’t good enough.”

In its early years, HTA was little more than a middleman between the state and HVCB, Kim says. It developed an “incest relationship” in which the same people, or at least people from the same entities, sat on both HTA and HVCB boards.

That’s changed. Evidence of this shift is that HVCB is now just one of many marketing contractors to HTA, although still the biggest, with responsibility for North America. Other contractors oversee Japan, the rest of Asia and Europe.

A tension has developed. The tourism industry is seeking, Carey notes, a stronger voice on the HTA board, while other people – particularly those in politics, such as Kim – want to ensure a larger public interest to balance industry concerns.

While the HTA has no shortage of strategic plans, one thing missing is a long-term view of how Hawaii ought to be marketed in profoundly changed economic times, argues University of Hawaii economist James Mak. Mak is author of a recent study of tourism in Hawaii, “Developing a Dream Destination (University of Hawaii Press, 2008).

“There hasn’t been much work that has been done on marketing in a crisis situation,” Mak says. When money was abundant and people were eager to travel, Hawaii had to do little more than remind travelers that it was here, arms open and eager for visitors. That’s changed, as consumers everywhere are watching their budgets and cost-conscious corporations cancel incentive and convention trips to Hawaii.

“Hawaii was successful in creating a brand image, and now that image has come back to bite us,” Mak noted. His point is that Hawaii has successfully marketed itself as a place where pleasure and leisure dominate. That’s not a strong selling point – particularly for business and incentive travel – when austerity and budget concerns are the order of the day.

Mak thinks, and Carey and others agree, that the strategy now is to identify and focus on those areas and market groups that are still willing and able to travel. Carey says he believes HTA is already moving in that direction with focused (HTA calls it “tactical”) attention on geographic areas on the Mainland and specific economic groups in Japan and elsewhere who still imagine Hawaii in their travel plans.

Says Mak: “The old strategy of throwing more money at it is not enough anymore.”