Teens Say No to Driver’s License

Driver’s licenses have been a symbol of adulthood and freedom for generations of Hawaii teens. But today, a much smaller proportion of youths are getting their licenses. We examine why and what it means for Hawaii going forward.

For decades, owning and driving a car has been part of the American dream. But, across the nation today, fewer people are taking the first step: getting a driver’s license.

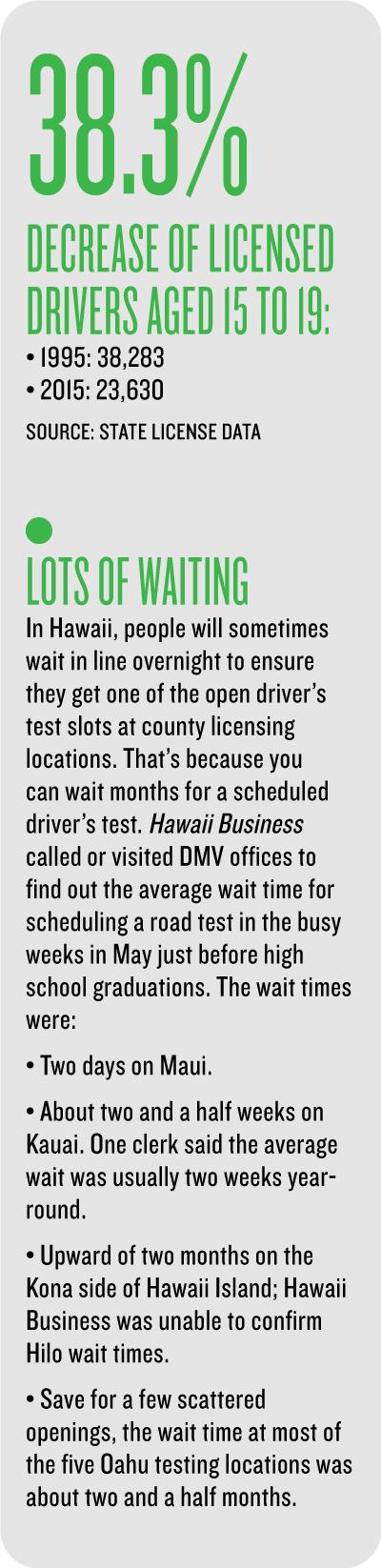

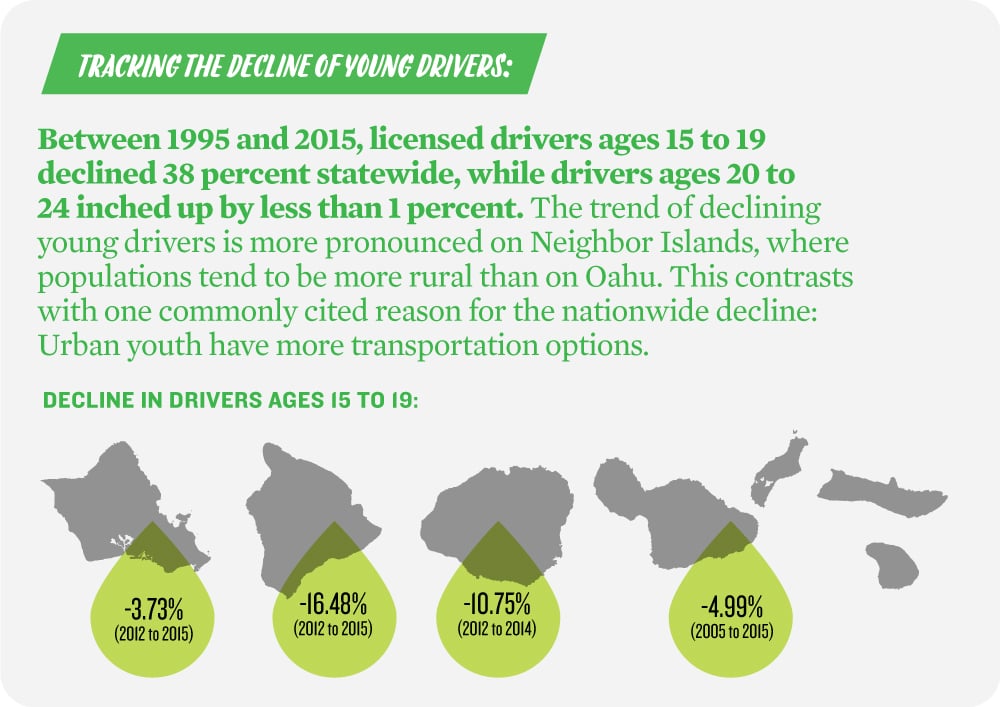

In Hawaii, 38 percent fewer residents ages 15 to 19 have their driver’s licenses now than did in 1995, according to state statistics. Money is a big factor, says Anita Lorz Villagrana, national manager of community affairs and traffic safety with AAA.

In Hawaii, 38 percent fewer residents ages 15 to 19 have their driver’s licenses now than did in 1995, according to state statistics. Money is a big factor, says Anita Lorz Villagrana, national manager of community affairs and traffic safety with AAA.

“It costs about $9,500 per year to drive when you add in everything from insurance to maintenance,” she says. “One of the things we heard when we were in Hawaii teaching classes was that kids feel like they have other ways to get around. They can walk, bike, ride with family members. They don’t see the need to drive.”

Social media is another reason young people delay getting a driver’s license. “Back in the day,” Villagrana says, “you’d drive to meet your friends at the movies and other places … Now, teens are reporting they can feel connected through Facebook, Twitter or Instagram, and they don’t feel the need to go as many places as they used to.”

A comprehensive 2013 nationwide survey conducted by Brandon Schoettle and Michael Sivak, scientists at the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute, concluded the No. 1 reason for Millennials delaying or avoiding getting licenses was they were too busy or didn’t have enough time. Other top reasons included the cost, the ease of using other transport, and a preference to bike or walk.

The decline in licensed young Hawaii drivers began in the 1990s, but accelerated around 2005. One reason could be the launch of Hawaii’s graduated licensing law in January 2006, which required young drivers to undergo training to get a license. Other states with graduated licensing laws also have fewer young drivers, according to a 2015 report by the same University of Michigan researchers.

Under Hawaii’s law, 16-year-olds must pass state-certified driver’s education classes. Public high schools statewide charge about $10 for the series of classes, but, in some areas, demand outstrips availability, forcing schools to hold lotteries for the coveted spots. Students left out can take courses from private instructors charging as much as $550 or wait until they are 18, when the classes are no longer required to get a license.

Kamalani Duerksen of Alii Driving Academy in Kailua-Kona thinks the shortage of low-cost classes is the reason for the decline in licensed young drivers.

“I don’t think the price of a car plays a huge factor here. Families tend to share cars and many students don’t feel it’s necessary to get their own car,” says Duerksen, a Realtor who started her driver-training company when she noticed the limited options in Kona. “Another thing that is becoming an issue is that the DMV is so backed up with driving tests, it could take seven or eight weeks to get an appointment for the necessary road test … I’ve had some students share that they have peers who drive without licenses.”

Namoi O’Dell, the vehicle registration and licensing administrator for the County of Hawaii, agrees with Duerksen.

“The (local) decline may be a result of not enough driver-training instructors on the Big Island and the cost of private-driver training,” she says via email. “The DOE system is overloaded with students applying for classes and there are long wait lists.”

There is also a burden on parents: During the learner’s-permit stage, parents must accompany their children while they drive at least 50 hours, including 10 at night. Parents must also accompany their children on some trips after they get their licenses. And both parents must sign children’s applications, which can be challenging if the parents are separated or one lives outside of Hawaii.

“One of the things we heard in Hawaii is that parents don’t realize the time commitment it takes to go through GDL,” AAA’s Villagrana says about graduated driver’s licenses. And parents often don’t realize that restrictions remain after 16-year-olds get their initial licenses. “They thought their teen would be able to take all the other siblings in the car to school,” she says, but there are restrictions on driving with others in the vehicle.

The graduated licensing requirements may frustrate some people, but they were created to produce safer young drivers and save lives, says Derek Inoshita, spokesman with the state Department of Education, which administers the required classes. “GDL goals are to provide more time and training before maturing teens can receive a full license to increase safety and produce better drivers.”

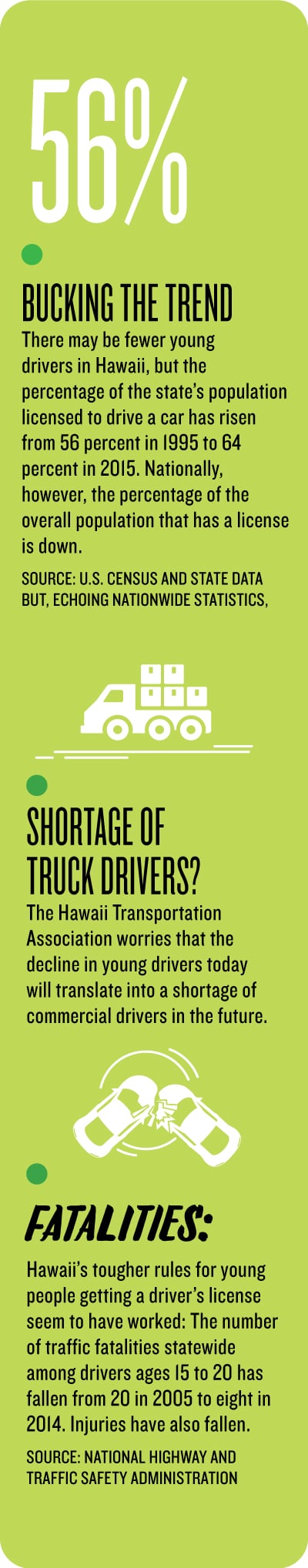

That seems to have happened: The number of traffic fatalities statewide among drivers ages 15 to 20 has fallen from 20 in 2005 to eight in 2014, according to the National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration. Injuries have fallen, too.

Villagrana says there is even further evidence of the efficacy of GDL programs. GDL rules in Hawaii only apply to 16- and 17-year-olds; once you turn 18, you don’t need driver’s education classes or 50 hours of driving with your parents. One consequence: Among drivers ages 18 to 21, car crashes are up, both in Hawaii and nationwide. “We believe it can be attributed to older teens not going through GDL,” Villagrana says. “It’s kind of pushing that curve up a little bit.”

Consequences

Fewer drivers coming through the pipeline could have significant consequences for Hawaii. The Blue Planet Foundation, which focuses on renewable energy in Hawaii, says it used data from the state Data Book to make a forecast. “If these trends continue, Hawaii should see a pretty dramatic decline in total drivers, even though, by 2040, we anticipate some 300,000 new residents,” says Shem Lawlor, Blue Planet’s clean transportation director.

Fewer drivers coming through the pipeline could have significant consequences for Hawaii. The Blue Planet Foundation, which focuses on renewable energy in Hawaii, says it used data from the state Data Book to make a forecast. “If these trends continue, Hawaii should see a pretty dramatic decline in total drivers, even though, by 2040, we anticipate some 300,000 new residents,” says Shem Lawlor, Blue Planet’s clean transportation director.

“What we do know is this trend is not a blip or an error. We can say with high confidence that the trend is real and it’s pretty impactful.”

Other numbers from the state Data Book suggests change could already be happening. Per car annual miles traveled – a key driving indicator – rose in most years from 1995 to 2013, but in 2014 fell to the lowest level since 2005.

Gareth Sakakida of the Hawaii Transportation Association, a trade organization formed by the ground-transportation industry, says the HTA is aware of the trend. What will come of it? “Nothing good,” Sakakida says. HTA sees the trend translating into a shortage of commercial drivers. “When I drive by schools,” he added wistfully, “I’ve noticed there are way less cars there than there used to be.”

For others, the dearth of young drivers is an opportunity. Ben Trevino, president & COO of Bikeshare Hawaii, says, “We’d really like to make bikeshare an attractive option for all age groups, but we do think people at this age are looking for alternatives to car ownership.” A survey by Bikeshare Hawaii in February 2016 found that 76 percent of respondents ages 18 to 34 said they would most likely try Bikeshare when it arrives; that was the highest response among any age group.

Lyft, a rideshare service, has been operating in Honolulu since 2014. Company representative Mary Caroline Pruitt says a nationwide survey of seven major metro areas found that 60 percent of respondents would use their personal vehicles less because of Lyft and 46 percent said they would continue not to own a vehicle or give up their vehicle entirely because of Lyft.

Lyft, a rideshare service, has been operating in Honolulu since 2014. Company representative Mary Caroline Pruitt says a nationwide survey of seven major metro areas found that 60 percent of respondents would use their personal vehicles less because of Lyft and 46 percent said they would continue not to own a vehicle or give up their vehicle entirely because of Lyft.

“Although the survey was not conducted on passengers in Honolulu,” wrote Pruitt in an email, “it shows how many people are increasingly relying on Lyft as their main way to get around town, making them less likely to need their own car.” (Repeated inquiries to Uber were not answered.)

Hawaii car dealers are not overly concerned about the dwindling number of young drivers. Dave Rolf, executive director of the Hawaii Automobile Dealers’ Association, says he anticipates the number of personal cars and trucks on Hawaii roads to remain consistent over the next 20 years.

“If Millennials weren’t buying as much, in theory there would be a dent in car sales. But, it’s actually just the opposite, car sales in Hawaii are up,” he says. Rolf says the rhythms of local car sales seem to follow the housing market: “We think that, when the price of housing is going up, people’s equity is found in their houses and many of them use that as an ATM to make car purchases.”

Rolf says his figures on new car sales may not reveal Millennials’ buying habits because young people often buy used cars.

A national report in 2013 by an economist for the website Edmunds.com showed a wavering but clear decline in the purchase of new cars by people ages 18 to 34 compared with previous generations. For instance, from 2007 to 2011, the share of car sales to buyers in the 18 to 34 age range fell by “nearly 30 percent.” The report suggested the reasons could be a weak job market, sluggish income growth and other economic factors “rather than from a preference not to drive.” In fact, it goes on to say that Millennials’ share of the country’s luxury car purchases has increased, and their “buying choices suggest an interest in cars that will translate into more purchases when economic conditions allow.”

Brian Gibson, executive director of the Oahu Metropolitan Planning Organization, says fewer younger drivers is “an interesting trend,” but says it’s too early to start changing transportation planning. “When (younger drivers) start to get married and have kids, are they all going to buy SUVs? To start making any huge changes now would be premature.”

A more interesting question, Gibson suggests, is whether fewer young people getting their driver’s licenses actually translate to fewer vehicles on the road. A report by INRIX, a company that crowd-sources nationwide traffic information data from 275 million vehicles, ranked Honolulu 10th worst in the nation for traffic congestion, with the average driver wasting about 49 hours in traffic in 2015. Gibson says that congestion and limited parking affects people’s decisions to venture out.

A more interesting question, Gibson suggests, is whether fewer young people getting their driver’s licenses actually translate to fewer vehicles on the road. A report by INRIX, a company that crowd-sources nationwide traffic information data from 275 million vehicles, ranked Honolulu 10th worst in the nation for traffic congestion, with the average driver wasting about 49 hours in traffic in 2015. Gibson says that congestion and limited parking affects people’s decisions to venture out.

“If I lived in Kapolei or Mililani and it’s a Saturday afternoon or even a weekday evening and I want to go to my favorite restaurant downtown, I make a mental calculation – maybe I’ll go somewhere closer or stay in,” he says. “When you improve traffic flow by adding a lane to the interstate or by opening up a secondary road, you increase the throughput of people from one area to another. Suddenly, my cost, which is my time, goes down.”

“I think there is a strong need to change transportation planning paradigms at both the state and county levels,” says Lawlor of the Blue Planet Foundation. “For many decades, transportation planning has been dominated by one primary metric: level of service. This is a measure of how many vehicles are moving at what speeds on roadways.

Under this paradigm the problem is always defined as traffic congestion and the solution proposed is almost always adding more lanes. Since this metric dominates transportation planning, other issues such as overall mobility, energy use, transportation equity or household transportation costs tend to be ignored.”

“There used to be a lot of social capital in having a nice car. Today cars tend to be less of an object of freedom and more of a cost burden,” says Lawlor, who then cautions: “If the state and counties do not recognize the changing transportation demands, many people may ultimately be forced to become drivers and others may simply lose mobility.”

Cost of Hawaii Car Ownership:

Good and Bad

- Hawaii is the 10th cheapest state for car insurance rates, according to insure.com.

- “Dealer documentation fees,” the taxes and additional costs associated with purchasing a new car in Hawaii are fifth-lowest in the country, according to mojomotors.com.

- Hawaii ranks 18th most affordable as a state in which to own a car, according to a 2014 study from Bankrate. The data estimates the costs of repairs, insurance and gasoline for the state of Hawaii to be around $2,162 annually. The cost did not include buying the car. AAA’s estimate for the cost of car ownership nationwide, which includes average car payments, is $9,513. It does not have state rankings.

- A study by GoBankingRates.com includes the cost of buying a vehicle plus the annual operating costs, plus sales tax or excise tax, title fees, registration fees, insurance, gas and car maintenance. Hawaii was among the most expensive states, ranking 40th. The price of gasoline was a major factor.

- Hawaii regularly ranks as the state with the highest gas prices in the nation and is only occasionally outranked by the District of Columbia, Alaska or California, according to multiple sources, such as AAA, gasbuddy.com and the U.S. Energy Information Administration.