Taking Advantage of Aloha

Financial abuse takes many forms in the Islands

It’s the plot to countless Victorian whimsies: Some accidental mix-up at birth is unveiled or a rich but distant relative dies and leaves you millions. And though ticketless lottery wins, secret inheritances, buried treasure and other windfalls are so scarce as to be almost nonexistent, plenty of people still hold out hope – and unscrupulous people are waiting to exploit that hope.

From phishing scams and fake romances to more nefarious plots like a bookkeeper stealing millions from a local nonprofit, financial abuse is rampant in the Aloha State.

What is Financial Abuse?

Put simply, “Financial abuse is the exploitation of the victim by coercive or deceptive means where the victim’s vulnerabilities (i.e. frailties or diminished mental capacities) are leveraged toward defrauding the victim out of his or her assets,” according to Capt. Gail Beckley of Honolulu Police Department’s Criminal Investigation Division’s Property Crimes.

That definition may sound straightforward, but in reality financial abuse ranges from crossing a fine line to a glaring injustice. Andrew Rosen, president and CEO of Hawaii State Federal Credit Union notes how difficult it can be to spot abuses: “There are times when it’s real hard to tell if what you’re seeing is really financial abuse or it’s someone willingly sharing money or co-management of their financial resources.”

Rosen says that when he managed his elderly father’s finances before the older man’s death, he could easily see how others might suspect that his actions constituted abuse, even though Rosen was acting in his father’s interest.

“The scammer is after everybody and whoever bites, that’s who they want.”

– Lisa Nakao, Hawai‘i office manager, Better Business Bureau Northwest and Pacific

Another reason it’s hard to pinpoint financial abuse is that it takes many forms, including fraud, scams, theft and deception. Complicating the matter is that many victims are embarrassed or confused by abuse and often don’t report it. As Kaipolani Cullen, the volunteer coordinator for Senior Medicare Patrol Hawaii puts it, “You’re not going to get everybody to admit it, or some people just don’t even know that they’ve been swindled.”

Financial abuse is an insidious crime because it plays on people’s vulnerabilities. It can also come at the hands of a trusted individual like a family member or close friend. Rosen’s view of financial abuse is narrower than HPD’s: “I think just the difference between fraud and ID theft and financial abuse is financial abuse is someone you know and trust taking advantage of the relationship,” he says.

Who’s at risk?

The short answer: everyone. “The scammer is after everybody and whoever bites, that’s who they want,” says Lisa Nakao, the Hawai‘i office manager for the Better Business Bureau Northwest and Pacific.

The BBB conducted a study to create a profile of the most common victims of financial abuse. The results were surprising: “As far as the frequency, the number of times that fraud was committed, it happens a lot more often to younger people,” 18- to 24-year-olds, says Nakao.

This demographic often falls for online purchase fraud, according to Nakao. They may order goods from nonreputable sites and never receive the products, or get something other than what was promised. There are countless memes and clickbait articles dedicated to online shopping fails. While some can seem funny at first, they do represent actual money lost, often by individuals who can’t afford it and likely have no recourse.

Another fraud that young people are susceptible to is messages from hacked email and social media accounts requesting money or online gift cards. “Something that’s communicated through the messenger or through social media, they might believe that and follow through with it and fall for that type of fraud,” says Nakao.

Financial abuse is often paired with domestic violence. A study by the Center for Financial Security at the University of Wisconsin-Madison indicated that economic abuse occurs in 99 percent of domestic violence cases. This can take the form of an abuser managing family funds, preventing a victim from working, hiding assets or otherwise asserting financial dominance in the relationship. Economic exploitation is one reason why it is so difficult for victims in abusive relationships to break away as they often have little access to money and other financial resources.

But, while young adults and domestic violence victims are often victims of financial abuse, the group most likely to lose a lot of money to financial abuse is kūpuna. “The amount of loss per fraud is much more significant for seniors,” explains Nakao.

Why Kūpuna are targeted

Proportionately, Hawai‘i has a large senior population. In the U.S., 15.6 percent of the population is older than 65; in Hawai‘i, seniors account for 17.8 percent of the population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. This may be partly because Hawai‘i has the longest life expectancy in the U.S. at 81.3 years, compared to 78.9 years for the whole country, according to a 2018 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The size of the senior population increases its vulnerability, as do the seniors’ assets, such as homes, other property and savings. Many seniors have owned homes long enough to have paid off their mortgages. It might seem improbable that anyone could exploit a home’s equity, but that has happened several times locally.

In 2013, Susan Chin was convicted of stealing $600,000 from 86-year-old Katherine Ganeko, by selling her home and keeping the proceeds. Chin had been the caretaker for the older woman who suffered from dementia and persuaded Ganeko to grant her power of attorney. With that power of attorney, Chin was able to sell the house, then transferred the profits to personal accounts that Ganeko lacked access to. Chin was successfully prosecuted, ordered to pay restitution and sentenced to 10 years in jail. Unfortunately for Ganeko, the home was sold to a legitimate buyer and could not be reclaimed.

This case highlights two issues kūpuna face as potential targets for scammers: They are often trusting, and power of attorney is a mighty tool once granted.

Val Mariano, branch chief of the Crime Prevention and Justice Assistance Division at the state Department of the Attorney General, is more succinct about why kūpuna are often victims: “Our folks in Hawai‘i are targeted because of our aloha.”

The aloha spirit is a beautiful quality but it can be manipulated. Trusting people – you might call them gullible – are easily swayed into believing that others have their best interests at heart. One way this trust is violated is through the misuse of powers of attorney.

A power of attorney is a written document that authorizes one person to manage another person’s personal, financial and legal affairs. Anyone can grant power of attorney over their affairs to whomever they want and for whatever reason. It lasts for the life of the person granting it, or until that person removes it. Power of attorney can be rescinded at any time, unless courts have already become involved for some reason, such as diminished mental capacity. Granting power of attorney to a dishonest person can be catastrophic, as Ganeko discovered.

Seniors can also be victimized if they are isolated and lonely. People who live by themselves are more likely to seek social interactions with anyone willing to talk story, such as a hair stylist or unknown caller, and reveal personal information that allows scammers to steal their identity. Seniors also tend to have predictable routines and may suffer from mental or physical impairments due to age. All of these factors make kūpuna prime targets for financial abuse with high price tags.

Protections in Place

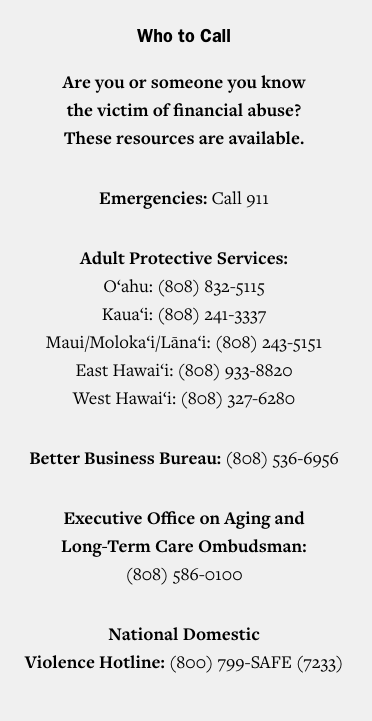

Thankfully, agencies are available to help.

Adult Protective Services, part of the Hawai‘i Department of Human Services, investigates reports of abuse of vulnerable adults and intervenes with short-term services for adults who are abused, neglected or exploited. Anyone can contact APS when financial abuse of adults is suspected.

Financial institutions also try to protect their clients from fraud and abuse. Many banks and credit unions train employees to spot hallmarks of financial abuse, particularly among elders. Employees notify bank management, and sometimes the police, about large cash withdrawals and other suspicious behavior.

Finally, police departments can investigate and assist in cases of financial abuse, which can lead to criminal prosecution. However, cases of financial abuse are notoriously hard to prosecute – sometimes because the victims often still trust their abusers. “So many of these people, even after they’ve lost hundreds of thousands of dollars, they will still stand up and say, ‘I trust this person, I believe that this person is interested in me, and I want to share my life with them,’ ” says Cullen.

Another reason cases are hard to prosecute is that many of them are perpetrated by family members. The Honolulu city prosecutor’s office found that about 64 percent of all elder abuse cases were committed by family members. Family disputes are touchy, and victims may not want to pursue legal charges. That’s one reason why it’s suspected that elder financial abuse is an underreported crime.

Keep Your Finances Safe

Be proactive to protect yourself from financial abuse. Review your banking, medical and credit alert statements regularly to ensure there are no fraudulent charges. Rosen recommends signing up for text alerts from your credit and debit card companies that let you know where your cards are being used. “Visa has a statistic that just signing up for those text alerts for your cards can reduce fraud by over 40 percent,” says Rosen.

Beckley offers this advice: “When possible, mail letters containing confidential or financial information from the post office instead of your home mailbox. Consider switching to online bill paying. Regularly monitor your financial accounts and billing statements and check your credit reports. Shred all discarded mail containing personal information.”

Beckley offers this advice: “When possible, mail letters containing confidential or financial information from the post office instead of your home mailbox. Consider switching to online bill paying. Regularly monitor your financial accounts and billing statements and check your credit reports. Shred all discarded mail containing personal information.”

In all cases, do not give away personal information over the phone or via email, because there are many ways swindlers can financially abuse you using even basic information. And remember when reviewing emails, phone calls or mailers, if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

Hawaii Business staff writer Noelle Fujii contributed to this report.