Restoration of He‘eia Fishpond Nears a Major Milestone

Paepae o He‘eia has spent decades removing mangroves and rebuilding the fishpond wall. The nonprofit is now gearing up to start sustainable fish production.

A pioneer and leader in the restoration of Hawai’i’s fishponds – Paepae o He’eia – is getting closer to the ultimate goal of sustainable fish harvesting.

The nonprofit founded in 2001 is dedicated to restoring He‘eia Fishpond at the edge of Kāne‘ohe Bay, says Executive Director Hi‘ilei Kawelo. Before 20th-century development, she says, there were about 30 fishponds in Kāne‘ohe Bay, “but many of them got filled in to make way for residential.”

He‘eia Fishpond escaped that fate; instead, it fell into disuse and disrepair after a 1965 flood destroyed parts of the wall and mangroves and other invasive species took over.

In the beginning, Kawelo says, the nonprofit was 100% focused on removing the mangroves because “you couldn’t see the horizon. You couldn’t see the fishpond wall, couldn’t see the water’s edge. It was just a wall of mangrove all the way around the pond.”

Staff and volunteers later started rebuilding the fishpond wall, whose skeleton was still there. “All of the wall has been restored. … We’re almost done with the mangrove. We’re not done with the other weeds or the invasive jellyfish or the invasive seaweeds,” says Kawelo. They are also working to reduce the carnivorous fish that live in the pond and eat the more desirable fish.

“One to two more years of restoration and then we’re done, and the focus has to shift to food production,” she says.

“One day, we’re going to feed people from the pond. I don’t know how many people. I don’t think we’re going to be feeding 6,000 people, like this pond fed historically. But … during Covid we were able to feed our volunteers meals that were 100% sourced from the fishpond.” Feeding those participants would be a good start, Kawelo says.

They are already harvesting Samoan crab, an invasive species that they sell for $10 a pound about once a month via phone orders. Occasionally, the crab is a special at some restaurants.

“We’re catching things like barracuda, pāpio and ulua that are predating on the more desirable fish that fishponds were built to grow, like mullet,” says Kawelo.

“We don’t sell those. It’s sort of just for staff (to eat) and we have fishing days that are open to the public, once a month, April through September.” The dates of their Lā Holoholo (family fishing days) and lottery sign-up are posted on their Instagram page, @paepaeoheeia.

About 2,000 Volunteers a Year

Paepae o He‘eia has eight staffers, seven interns in the summer and volunteers year-round. Kawelo estimates the nonprofit gets “maybe 2,000 volunteers” a year; most come from school groups, but it also gets help from individuals, families and companies.

“If you come to volunteer at a fishpond, it’s not going to be easy. But I think that people like that. They leave feeling good about their contribution, even if it was the muddiest thing they’ve ever done in their life.”

From 1200 to 1600, Native Hawaiians built and maintained hundreds of fishponds (loko i‘a) across the Islands. But colonialism, cultural suppression, urbanization, natural disasters and invasive species led to their destruction or deterioration.

“Fishponds had a pretty simple purpose and function, and that was to cultivate fish and supply our people with protein,” says Kawelo. In its heyday, the 88-acre He‘eia Fishpond “could supplementally feed a population of about 6,000.”

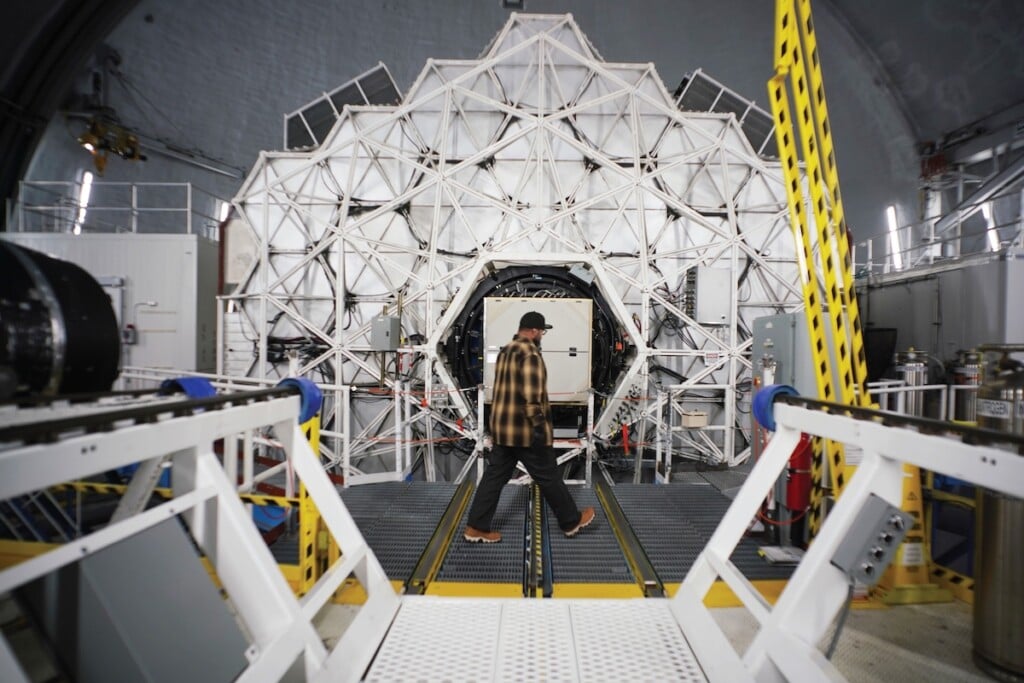

The pond wall is made of volcanic rock and coral and is 11 feet wide at the top. | Photos: Jeff Sanner

And it was sustainable. “Hawaiian fishponds are Indigenous aquaculture systems. Indigenous aquaculture systems are designed using ‘ecomimicry’ principles, which means that they enhance the existing environment, rather than detract from it as commercial aquaculture systems often do,” says Kawika Winter, director of the He‘eia National Estuarine Research Reserve.

He‘eia NERR co-manages the He‘eia Fishpond alongside its partners, including NOAA, UH’s Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology and Paepae o He‘eia. He‘eia NERR’s research helps to identify and remedy fishpond problems.

“What is clear from a scientific perspective is that it takes more than removing invasive mangroves to make a fishpond as productive as it was in ancient times. Fishponds need certain environmental parameters to exist in the larger system to function properly. These include things like freshwater inputs, water quality and fishery health,” says Winter.

Built Where Streams and Ocean Meet

Hawaiian fishponds are strategically located where freshwater streams meet the ocean, creating brackish water environments.

“The idea is that fresh water mixing with salt water creates the (right) habitat for the phytoplankton, which feeds the fish,” says Kawelo. This eliminates the need for people to feed the fish, a common practice at most commercial fish farms.

He‘eia Fishpond’s 1.3-mile wall is made of volcanic rock and coral and is 11 feet wide at the top. Interspersed along the wall are slatted gates, which allow small, young fish to enter the pond; those fish eventually grow so large they become trapped. The walls and gates also help maintain the right ratio of fresh water to salt water.

Slatted gates like these allow young fish to enter the pond from Kāne’ohe Bay, but after the fish grow, the gate keeps them inside the pond. | Photos: Jeff Sanner

“It’s kind of like a recipe, right? More fresh than salt (water), I’d say. You’re trying to cultivate the kinds of phytoplankton that the fish you want eat,” says Kawelo.

She says fishponds were built “to cultivate primarily Hawaiian striped mullet,” commonly called ‘ama‘ama in Hawai‘i, “but it’s a “super diverse ecosystem.”

“You have the phytoplankton, but then you have all the little critters like the crabs and shrimp that keep things clean on the bottom. You have filter feeders, like oysters and clams. You have macroalgae that other fish eat, like ‘awa, which is another fishpond fish. And then there’s other kinds of herbivores and other kinds of seaweed. And then you have omnivorous fish that eat shrimp” and other things.

The Bigger Picture

Paepae o He‘eia is part of a network of fishpond caretakers across the Islands called Hui Mālama Loko I‘a. Its coordinator, Brenda Asuncion, says it formed “out of this idea that people working to steward and restore fishponds could learn from and support each other.”

The network covers about 60 sites, including nonprofits, family-owned fishponds, and private properties such as resorts that have staff members who take care of fishponds.

“Some of the sites that are in the network have just identified that they have a loko i‘a and they want to be a part of a network where they can meet and learn from other people. And then some sites have dedicated staff or have community efforts that work on them,” says Asuncion.

Paepae o He‘eia is seen “as a leader in the network. More and more are growing and starting to do amazing things, too. But everyone still looks at them as a kind of pioneer organization, for sure.”

Asuncion emphasizes that fishpond restoration is not only about reinstating a sustainable food source: “When people talk about the function of fishponds, it really was to increase the abundance and ability to get food, but at the same time, there’s this whole rich understanding of how loko i‘a feed us in non-physical ways.

“They’re opportunities for us as people and community members and Hawaiians to connect to our lands and waters and have relationships with places that are meaningful to our lives.”

Winter shares a similar sentiment: “Restoring fishponds is not only for Native Hawaiians, and it is not only about holding on to the legacy of our ancestral past. Restoring fishponds is about reviving a way of thinking and being in Hawai‘i that allows us to thrive together with our environment, rather than at the expense of it. Many of our kūpuna have said that Hawai‘i can heal the world. This is a part of what they were talking about.”