How Family Businesses Survive and Thrive

As Baby Boomers retire, thousands of local family businesses are facing difficult transitions to the next generation. A groundbreaking local survey identifies challenges and solutions. Here’s how family businesses can survive and thrive.

There’s a perfect storm ahead, and most of Hawaii’s family businesses are not prepared. That’s one conclusion from a groundbreaking survey of owners at about 140 family-owned local companies. The first-of-its-kind survey was conducted by research company Market Trends for Business Consulting Resources, a locally owned company that advises family businesses.

“Family businesses are facing a huge challenge in the coming years, and it impacts the economy of the state because Hawaii has so many family businesses,” says BCR senior consultant Laurie Foster. “If they don’t manage this transition well, Mainland corporations will come in and scoop them up.” Or worse: Those family-owned companies could go out of business entirely.

Hawaii has seen many family businesses that have survived and thrived through generations of transitions. But many other local family businesses have imploded and destroyed relationships along the way.

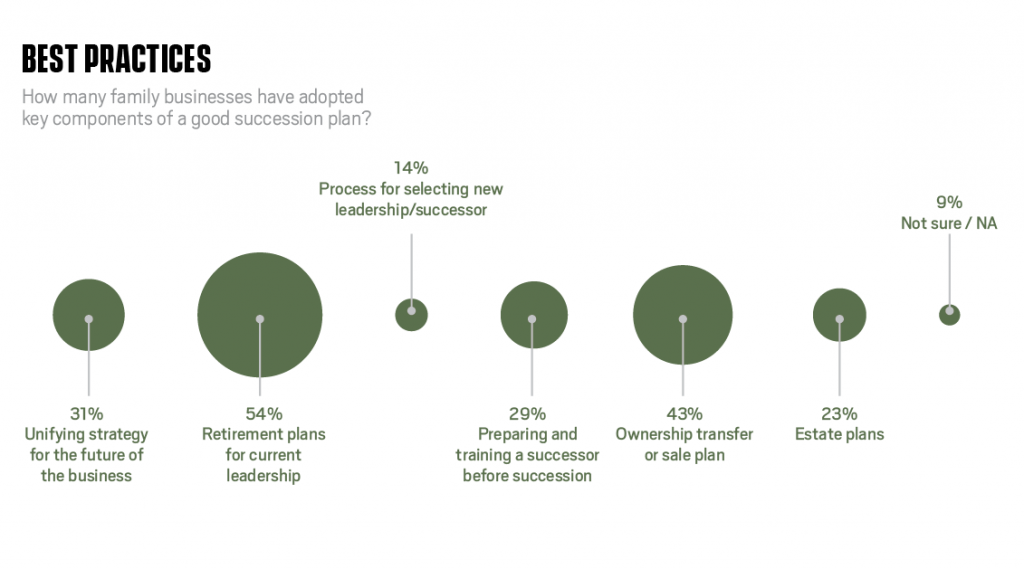

Foster says Baby Boomers are getting ready to retire, setting the stage for the largest transfer of generational wealth ever in Hawaii. “What the survey tells us is that a lot of Hawaii businesses are coming close to the time when they have to make the transition to the next generation, and the readiness factor is rather low,” she says. “If you’re planning a transition in the next five years, you really have to get on it.”

Court files are full of the wreckage of families whose poor transition planning left brothers and sisters at war. One of the most public in Hawaii involved the family of Hiram Fong, which battled for years in court and left a trail of bankruptcies and anger.

The Kelley family led one of Hawaii’s most successful family businesses: Outrigger Hotels and Resorts. Seated are founders Estelle and Roy, with (from left) “partners” Pat, Richard and Jean, circa 1955.

“There’s a lot of drama in family business,” says Prof. John Butler, faculty director of the Family Business Center of Hawaii, which is based at UH Manoa’s Shidler College of Business. “There’s a lot of drama in all families, and in all businesses, and when you combine them, what you end up with are family members who are working in the business, some who aren’t, some who are owners, and some who may or may not be working in it. As the generations go on we become less close. We’re very close to our siblings but less close to our cousins, and certainly to our cousins’ spouses, so there begins to be pressure.”

With all those forces at work, says Butler, it often helps to have regular family meetings to wrestle with the issues and disputes, before the divisions become too deep. The first such meetings can be difficult, even painful, but they are necessary to help resolve issues that will otherwise fester and cripple both the business and the family itself.

The BCR survey was conducted in February and March, and focused on family businesses with five or more employees, which account for as many as 2,000 companies in the Islands. While the survey results tracked national trends, they were even more profound for Hawaii because of the central role that family businesses play in the state economy.

Foster hopes the survey raises awareness and creates a sense of urgency over launching a transition plan.

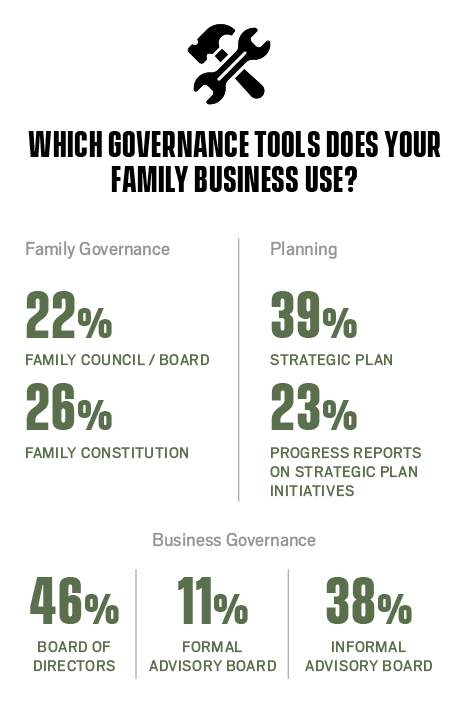

“Our rule of thumb is that it takes a minimum of five years,” Foster says. “Frankly, the earlier the better. The families that aren’t really ready for transition at all haven’t done some of the basic things, like establishing a family constitution that talks about the basic rules for families in the business, or establishing a family council and having both generations on it. And, literally, creating a succession plan.

Lanai Ocean Sports is truly a family business. On the left is Gabe Lucy, the company’s GM and director of operations, and on the right is Ginger Coon Lucy, director of corporate administration. In the middle are their twin children and baby.

“The Kelley family, for instance, has been doing this for three generations. It’s integrated into the way they run their business and their family wealth.”

Members of the Kelley family founded the Outrigger hotel chain in 1947 and owned and operated it for 69 years until selling last year to KSL Capital Partners LLC.

Ken Gilbert, Foster’s partner at Business Consulting Resources and a company co-founder, also says the Kelley family is a good example of how to work together to decide the direction of the family business.

“They were prepared and ready to entertain a significant offer to sell the company,” he says, “and when an offer of that caliber came in, they were able to react in a conclusive way, whereas many family businesses have a difficult time.”

The whole process of planning a succession or exit takes time. “You can’t hire a consultant and expect to have this wrapped up in six months,” Gilbert says. “It’s emotional. Conflicting. Difficult. And it’s a process. You have to move through the different stages of emotion, of conflict management, of difference of opinion. One brother wants to transition; the other wants to sell. The next generation says, ‘You’ve worked 24/7 your whole life. Why would we want to?’ There are all these things to consider.”

TRILOGY’S FAMILY

For Maui’s Coon family, close connections and succession planning are essential to the family consciousness, because the business has been family-centric from the beginning. His dad was the first generation, operating a luxury charter service in Alaska. When the boat tragically sank, family members pooled resources, had another built, sailed it around the Pacific and ended up in Hawaii in the 1970s. The father and his two sons founded Trilogy – the family’s luxury charter business that today operates from Maui to Lanai, Molokini and elsewhere – but both brothers raised their children in and around the boats, and with a sense that they, too, were part of the operation.

“Both of us told our kids that working in the family business was just what you do (growing up),” says one of the founding sons, Jim Coon. “I don’t think they thought about it. It was just part of our family life. They were in the kitchen baking cinnamon rolls – our signature product in the early days – and scrubbing pans. We told them this business was an opportunity, not an obligation, and if they had a passion for it, it was a good opportunity. But it wasn’t something we expected them to do.”

As toddlers in the kitchen, the children were already part of the team; as teenagers, they were gofers to earn spending money. “My son started to work in the maintenance department at 14, just helping around and learning how things go together,” says Coon. “As he got older he was given more responsibility, and eventually went on to get a degree in mechanical engineering. He understood how things went together.

“My daughters helped in the office. And my brother’s wife and children did the same. Our wives did much of the food prep as well. On weekends, we would answer the reservations line at home. Our family would take it one week, and my brother’s family the next. My kids could field the calls and answer the phone professionally, learning basic communication skills pretty young.”

Succession planning happened early and often for the Coon family, and today five of the brothers’ six children are in the business, and so are some of their spouses, providing a range of important skills that include legal, business, engineering and management. It means that Jim Coon and his brother will be able to let go – once they teach themselves that skill.

That may be one of the toughest pieces of the equation, Jim Coon admits.

The Coon family founded the Trilogy ocean tours company on Maui. Here Jim Coon, the patriarch of the family business, celebrates his 70th birthday with family – most of whom work in the business. His wife Lynn works in the business; Riley and Jenny (far left) are, respectively, director of operations and sales manager; MeiLi, who is holding her daughter, Keziah, is not currently in the business. On the far right are Mark, who used to be a Trilogy dive instructor, and LiAnne, who is the director of sales and marketing.

“I think it’s harder for me to let go than my brother,” he says, “because my area has been the compliance issue – working out agreements with the state – basically the politics of running the business. And those areas are based on relationships and a long track record of doing the right thing, and it’s hard to pass those relationships off to another generation. They now will have to build that trust level.”

Coon remembers his parents’ succession plan was simple: “Dad said, ‘You guys are running the business and we know you’re going to take care of us.’ ” That all came to pass, with their father helping as a captain right up to two weeks before he passed away.

Even with buy-in from one generation to the next, the Coons instituted useful strategies to make sure the operation was truly businesslike and to prevent jealously and other problems.

“Our adult children were not just coming into the business, but marrying people who they were also bringing into the business,” Coon says. “It became apparent they would do a great job running the operation, so what we did was take two of my brother’s kids, and two of mine, and formed the Executive Council. Then, when my brother’s son graduated from law school, he joined as corporate counsel representing the company. In my mind, he’s sort of like the lawyer sitting on the side giving advice to them on what’s the best way to do something from a legal and liability standpoint. His position is unique because he represents what’s best for the company.”

BCR’s Foster cited some dismal national statistics on the transition success of family businesses. “Thirty-three percent make it to the second generation,” she says. “And then 13 percent to the third. And 3 percent to the fourth generation and beyond. It goes down exponentially.”

That makes the Coon family one of the few that has figured out a successful formula. Jim Coon explains that success partly came from his and his brother’s conviction that family comes first.

“My brother and I had a commitment that our relationship was more important than the business and, if push came to shove, our relationship wasn’t going to be sacrificed for the business,” he says. “It’s vital that they (the next generation) get the same commitment. It’s one thing for brothers to work together – that in itself has its own challenges – but it was easier for us to find common ground. But the cousins have more challenges. Our two families had different cultures, that’s just life, so, for cousins to work together, there are more challenges than for siblings. What the Executive Council does is tend to help them work as a unit.”

UH’s John Butler agrees with Jim Coon that family should never be sacrificed for the business. “Family business owners should just recognize it’s not the worst thing in the world if the kids don’t want to continue in the family business,” says Butler. “The most important thing is to have a healthy and happy family. There’s no sense having a healthy and prosperous business if it ruins the family.”

Ken Gilbert applauds the Coon family’s Executive Council and the children’s early involvement in the business. He says it’s never too soon to start talking to the next generation about what it means to be part of a family business, and how that may impact them. “The sooner the better,” he adds, “Even if the kids are just 10, you should start the conversation.”

Within his own family, Gilbert says, he held the first family meeting about their own business when his twins were 6. Of course, the conversation was age appropriate, he explains, with the talk centering around “what Mommy and Daddy do.” But it was the beginning of a long discussion. Today, the twins are aged 19 and in college. One is going into a business entrepreneurship program, and the other is headed for law school after undergraduate work. Both tracks are beneficial for anyone heading into the business world – or perhaps thinking of one day stepping into mom’s and dad’s shoes.

LETTING GO

Sometimes business training happens on the job. That’s how it’s been for Lari Zelinsky-Bloom, who began helping her father in 2002 at The Zelinsky Co., handling large-scale painting contracts as he began planning to retire. With a background in insurance, Zelinsky-Bloom had no experience in painting contracting, but began taking a leadership role in the company in the 10 years leading up to her father’s retirement in 2012.

“Like most entrepreneurs his age, he wasn’t really emotionally ready to give it up,” she remembers. “His identity was his business. This was his baby. Even though he said, ‘The business isn’t fun anymore, and I don’t want to do it anymore,’ in reality he didn’t know what else to do. He didn’t have any kind of hobby.”

Zelinsky-Bloom doesn’t want the same thing to happen as she and her husband ease themselves out of the top jobs and gradually allow their son and a nephew to take the reins. The younger generation now has a good grounding in the company, she says, but one big question is: How will the employees accept two “kids” as bosses?

“The tough thing is having employees make the transition from me to the kid,” she says. “Earning the respect so they want to be managed by him is difficult.”

She remembers how hard it was when she first came in. “When I started taking over management, we lost a lot of our long-term employees. So I’m trying to let him (her son) start doing the hiring so that anybody new we bring in, he’ll be the face of hiring. I’m trying to lead from behind. I go to him and we discuss it, and then I let him handle it.”

Even with two committed third-generation family members, the continuity could be in question, she says. “We keep our fingers crossed. We don’t know what this new generation is going to do. There’s a commitment, but these kids nowadays have a different mentality, and you can see the change from where my dad started. Then it was business first and you make all the sacrifices you possibly can for the business. Then you get to my generation where you’re a workaholic but a little more resentful because you want to play more. And then you get to my kids’ age and it is work/life balance in their minds. They look at work and business as a means to enjoy life.”

The importance of stable family relationships is not lost on Dr. Charles “Chuck” Kelley, scion of one of Hawaii’s most successful family businesses, the Outrigger Hotels and Resorts chain that was sold a year ago to a Denver-based private equity firm, KSL Capital Partners. Kelley, a member of the third generation after his grandparents, founders Roy and Estelle Kelley, won’t specifically speak about his family’s business, but it’s obvious that he is astute about family businesses in general, and where both successes and pitfalls may lie.

“I would define success in a family business as being able to evolve and maintain those family relationships without destroying them,” says Kelley. “In the normal workplace, (if there are conflicts) you just move on to a new company. In a family you can’t, because those relationships are key to everyone’s happiness.”

Kelley says it’s often in the third generation of a family business that the company is sold, “because they say, ‘I’m not running it. I can take the proceeds and invest it and do something else.’

“It’s either sold for a profit or fails in the third generation. The odds are 95 percent this will happen.”

This should not necessarily be considered negative, he says. “We talk about failing as if it’s a bad thing. It may not be. In many cases the family business can evolve to something else. It can separate to allow new branches of the family to go their separate ways. So often it’s not a failure, but the evolution of a business to something else.”

The Kelley family was cited as one to emulate in local business guru David Heenan’s book “Leaving on Top: Graceful Exits for Leaders.” That book looked at the many positive ways family leadership passed the torch to the next generation.

“He highlighted some of what my father did,” Kelley explains. “The thrust of what he was talking about was the leader being able to step back and turn over authority and yet be able to stay engaged and monitor it without being able to interfere with the duties of the successor.”

That doesn’t always happen in other family businesses, says Kelley. “Usually the entrepreneur who starts the business never wants to give up control. It’s the nature of the entrepreneur. It’s a huge part of their life. They always plan to turn it over, but it usually never happens until they reach their 90s; they look at their son or daughter, who is 70, and say ‘OK, it’s yours now.’ And the son says ‘Sorry, I’m retired.’ And it often falls to the third generation, who would be in their 50s, and reaching their entrepreneurial prime.”

Kelley notes that those families who have successfully passed down the family business are often ones who brought their children into it early, offering them an understanding of the business so they could make a career choice.

“It certainly doesn’t work when the founders keep the family in the dark until some point when they say, ‘OK, it’s yours,’ ” he says. “You have to drive that interest. The families who do it well involve the entire family and provide a lot of educational opportunities, both formal and informal, to teach the family about it and to learn about pitfalls of other family businesses.”

A large family can be a plus or minus, says Kelley.

“The larger your family, the more likely you are to have a successor in the family business. On the other hand, the more likely you are to have in-fighting in the next generation about who is going to be successor, or disagreement within the family about the course of the business. Some say ‘We should aggressively grow the business.’ Others worry about cash flow. Others say, ‘No, just sell.’ The more people you have, the harder it is to satisfy those diverse interests.”

The study of family business is a subject of growing interest not just among private firms, but at universities and in banking institutions looking to establish lucrative relationships. Kelley says networking can be especially helpful.

“It’s better to learn from someone else than do it wrong,” he says. “That’s also where the money is. If you’re a private consultant, a university, a large bank, and you think, ‘How can I attract more customers?’ offering education about family business is a way to associate yourself with those groups. I don’t think that’s a bad thing. They provide valuable information. Families can benefit from learning about other family’s experiences to mold their own paths.”

3 Generations

Dr. Charles ‘Chuck’ Kelley, the third-generation CEO of Outrigger Hotels and Resorts until it was sold, lays out this typical generational chart for the growth of a family business:

I. “The originator who creates the family business is normally a strong, opinionated old entrepreneur who is a risk-taker. They tell their children how wonderful their opportunity is to get an education and how the education can give them a skillset they (the entrepreneur) never had.”

II. “So the second generation goes to college and becomes doctors, lawyers, engineers, architects, and other professionals, and they have good careers. The second generation grows up within the shadow of the first but without the trappings of wealth. They’re hard-working professionals.”

III. “By the third generation, the family is now wealthy. There’s cash flow. The 3Gs get multiple college degrees and say, ‘I’m smart enough not to have to work hard.’ And they take advantage of the opportunities given to them and become artists and lifeguards and ski patrols, which is a great lifestyle if you can afford it. And they can afford it.”