Staging a Race is No Walk in the Park

Photo: JJ Johson

The costs add up because even small sports events need planning, permits, cones, cops, signs, safety and much more

On any given Sunday, hundreds or thousands of weekend warriors are on the roads and in the ocean competing in run, bike or swim events around Hawaii. Whether you are in the race or stalled in traffic waiting for runners to pass by, you probably haven’t given a second thought to what it takes to stage these events.

JJ Johnson never did while competing on the local road-racing circuit back in the 1980s while stationed at Schofield Barracks.

“I used to blow by aid stations and not think twice about the cost of a cup or what it took to man an aid station or put a race together,” says the former world-class runner and California high school mile champion.

Photo: JJ Johson

Today, Johnson is one of the busiest race directors on Oahu and intimately knows how complicated – and expensive – it is to stage even small events.

The 2013 calendar on Running Room Hawaii’s website shows an average of nine events on Oahu each month; 13 were scheduled in both May and July. These small- to mid-size races draw from 200 to 5,000 participants, yet take up to a year to plan and organize. All that work has a cost and participants are expected to pay for the experience.

Jonathan Lyau accepts that price. The member of the Honolulu Marathon Hall of Fame has been a local race participant for nearly 35 years and recalls paying either $5 or $10 for his first road race, the Pepsi Challenge 10K in 1979. Today, a 10K entry usually costs $30 to $40, with triathlons and marathons typically costing $100 to $150.

“I probably don’t race as often because of the expense. But it’s accepted. I understand and know how expensive it is to put on these events, having been a race director for a one-time event,” says Lyau. “It takes a lot of work and there are a lot of things you have to pay for such as facilities, timing, T-shirts, safety, awards and food.”

Johnson is grateful for participants like Lyau, who understand the challenges of staging such events, but also knows that not everyone is as sympathetic. “The mentality of some of the athletes is, ‘It used to cost $35. Why is it $135 now?’ ” says Johnson. “Well, now things cost more, we have to cover ourselves. Now we need insurance.”

Like most Hawaii race directors, Johnson says, he does the work because of his love for and connection to the sport, but admits that making a little money is also a factor.

“If I was a concert promoter, bringing in the Bee Gees, Beach Boys or Usher for your benefit, why would I do it for free? It’s a business. And this is what a lot of athletes, who, by the way, are in business themselves, don’t understand,” says Johnson. “You wouldn’t go to work and say, ‘Hey boss, you don’t have to pay me today. I’m going to do this for free.’ ”

Photo: JJ Johson

Johnson organizes the Ko Olina Triathlon, the Hapalua Half-Marathon and the Honolulu Triathlon, and serves as director of course operations for the Honolulu Marathon. He also works for mainland groups that organize competitions in Hawaii.

Some mainland race directors who organize major events such as the New York City Marathon can make a full-time living off such races, but it’s strictly a part-time gig in Hawaii.

Johnson, who owns a fitness consulting business in Japan and specialized in logistics while serving in the Army, has done the math: His iPad contains detailed breakdowns of budgets, procedures and organizational charts for his races. The entry fee for this year’s Honolulu Triathlon is $125, he says, but it costs him $135 per athlete once all the bills are paid.

“I make up the difference through sponsorships, which vary from race to race … I need to cover my staff, race director, swim, bike, run coordinators, donations to volunteer groups and all of the vendors.” The Honolulu Triathlon is owned by a Japanese company and, like the Honolulu Marathon, brings in athletes from Japan through tour groups. Johnson expects around 800 participants for the May 19 event.

Every cup, banana and bagel is purchased. Nothing is free anymore, Johnson says. “There’s no such thing as anyone volunteering or donating these days. Now we have school or nonprofit groups manning aid stations and we give them a monetary donation to help us. Participants get a T-shirt, a finisher’s medal, an award if they place and food at the end.”

The third annual North Shore Marathon held on April 14 set athletes back $100 for the chance to run 26.2 miles. Finishers got a T-shirt, hat, towel, sticker, bag, license plate holder and food after the race.

North Shore Marathon race organizer Raul “Boca” Torres is known for keeping entry fees at a minimum for his events. The professional coach and owner of Boca Hawaii, a triathlon store in Kakaako, admits that he’s happy to make a little money putting on races, but it’s not his bread and butter.

“The training clinics, the store and our events all go hand in hand as part of the overall business. We have invested in some race-day equipment, such as bike racks and buoys, so we are able to cut back on some vendor costs. Sometimes we make money on an event and sometimes we don’t. You wouldn’t do it if you didn’t make at least a little bit of money, but I just like to do it,” says Torres.

Torres’ 808 Marathon Readiness Series includes five running events from August through November to prepare runners for the Honolulu Marathon. Entry fees range from $35 to $60 for each race and from $115 to $150 for the whole series, depending on when you register and other factors.

Johnson has a different view. “If it was my race, you would not be paying $35 or $40,” says Johnson. “No offense to any of the other race directors out there, but I believe in doing five-star events and, if people want to run a race here that will be a good experience, you have to pay for it.”

For instance, Johnson says, the Honolulu Triathlon that he organizes is the only triathlon in Hawaii, and one of the few in the United States, that shuts down city, state and federal highways and roads. “Think about the magnitude of just that. The permitting process, the buses alone that need to be rerouted. It’s astronomical. My police bill is $25,000 for 125 to 150 cops for those four hours during the race.”

Photo: KC Carlberg

KC Carlberg, the owner of TryFitness, a women’s training group, is the race director for many of Oahu’s women-only events, including Na Wahine Festival.

“If you get the infrastructure down, aside from the fixed costs, the more people you get, the more money you make,” Carlberg says. “Of course you don’t want to put on a race without making some money. It’s a business. People will say, ‘Well you make so much money.’ But after all is said and done, you’re lucky if you make maybe a couple of thousand dollars. If you’re really lucky, you get some extra money through sponsorships and you make maybe $5,000. And this doesn’t account for your time and energy.”

Na Wahine Festival draws 200 to 300 women each year and the Sept. 15 event will be the 15th anniversary running. The entry price has risen from $55 to $90 since it began.

Ask Carlberg about the permit process and she lets out a huge sigh.

“You start off by thinking, ‘I’m going to do a race in Waikiki.’ You need to go to the city and county for the street usage. Your plan has to be safe, make sense and can’t block major thoroughfares for long periods of time. Once they approve, you need buy in from the neighborhood board.”

Then, she lists some of the requirements you will face:

- Obtain a permit for Kapiolani Park or other park, and for that you must be a nonprofit or affiliated with a nonprofit.

- Get a water permit from the state if it’s an ocean race.

- Line up local vendors, everyone from bakeries to party suppliers.

- Organize traffic control.

- Ensure you have insurance.Carlberg gets hers through USA Triathlon, the organizing body of the sport. In addition to an entry fee, each participant pays $12 for a one-day racing license that includes insurance.

Both Carlberg and Johnson say it’s common that, after a year of planning for an event, permit approval will come 24 hours before the starting gun.

“The city will send you an email that basically says, ‘Here’s your permit,’ ” says Johnson. “They haven’t automated the system yet. We still apply by paper. And even though I have put on the same event for many years, I still go through the same rigamarole each year as someone who is putting on a brand-new event.”

For traffic control services, GP Roadway Solutions is often the choice for Carlberg and Johnson.

Kenneth Young, GP’s rental manager, says the company provides both traffic control for vehicles approaching the event site as well as coning and other controls for race participants.

“Our involvement is providing advance warning, signs, electronic message boards and coning,” says Young. “We just took care of the North Shore Marathon and it took about four guys and two trucks to do the coning. We were out there maybe seven hours.”

Young says costs vary widely. For a 5K race around Kapiolani Park, GP would charge $200 to $300. For a big event like the Honolulu Marathon, which runs from near Ala Moana Beach Park, through downtown and back to Waikiki, past Diamond Head, all the way to Hawaii Kai before returning to finish at Kapiolani Park, the cost can be tens of thousands of dollars.

Young says such events are important for GP and its sister company, Peterson Sign Co., but they only account for about 7 to 8 percent of their overall business.

Photo: JJ Johson

On the other hand, Steve Foster’s company relies solely on races. The full-time air-traffic controller moonlights as the owner of Pacific Sport Events & Timing, which provides timing systems and results for the Honolulu Marathon and other competitions. He sometimes wears a race organizer’s hat and stages local events such as the Firecracker Sprint Triathlon, Color Run and Waterfront Triathlon. His company also has a contract with Nike to provide timing for the Nike Women’s Marathon in San Francisco, which attracts 27,000 participants.

Foster charges event organizers by the participant – $2.75 per entrant – with a minimum fee of $850. There are always additional costs for items such as timing devices, usually a microchip supplied to each athlete, and timing mats that athletes make contact with along the course that connect to their timing devices and record their interval times, also known as splits.

Foster says the stress of being an air-traffic controller pales in comparison to the anxiety of a race director. “All of the coordination and planning, notifications, if you don’t have a large staff and have to do it yourself, it’s one of the biggest headaches,” says Foster, who coordinated the Honolulu Triathlon for four years before Johnson took over.

“It didn’t pay enough for my time,” says Foster. “I can put on a small race of my own and make the same amount in a weekend.”

Kenny Rust, owner of Aloha Surf Lifesaving, has also found a niche in the business of sports events. He worked for the City & County of Honolulu as a lifeguard for 30 years, then, 10 years ago, started a business providing water safety for events.

“The city used to help provide lifeguards for certain events, but after awhile, the city started to rethink the idea about helping folks with these moneymaking events,” says Rust. “Back in the old days, lifeguards would get paid like the off-duty cops on special duty, but that ended. That’s when I saw the need for a professional lifeguard company.”

Rust says roughly 25 percent of his business is work for swim or multisport events like the Tinman Triathlon, Waikiki Roughwater Swim and Ko Olina Triathlon. He provides lifeguards, buoys and jet ski patrols.

“I have a $5-million insurance policy that costs me $20,000 a year,” says Rust. “So I need to make enough money to pay my lifeguards well. The average rate I pay them is $35 to $50 an hour.” Many of his lifeguards are either off-duty or retired city lifeguards.

Rust and his staff were prepared to provide water safety at the Ko Olina Triathlon on Oct. 28, 2012, the day beaches were closed due to the tsunami that started off British Columbia.

The city called Johnson that morning and told him they were revoking his permit. Johnson recalls that picture-perfect day, standing on the beach at Ko Olina with Rust after notifying 450 participants that the race was cancelled.

“I was literally almost getting physically ill, because I was so sad for having to cancel,” Johnson says. “Everything was set up as planned and it looked fantastic. Kenny put his arm around me and said, ‘Look at the water, JJ. Isn’t it beautiful? What you don’t know is what’s happening beneath that water. All it takes is one swimmer to be sucked out into that lagoon and you’ll never have this race again.’ ”

Johnson lost $40,000 that day and will give those that signed up for the 2012 event a 50-percent discount for this year’s event. Some participants asked for refunds, Johnson says, but, he added, “There is no such thing as a refund, because if you ask a vendor to do a job in preparation for the event, they are going to do that job for you. Whether or not the event goes on as planned, people still need to get paid.”

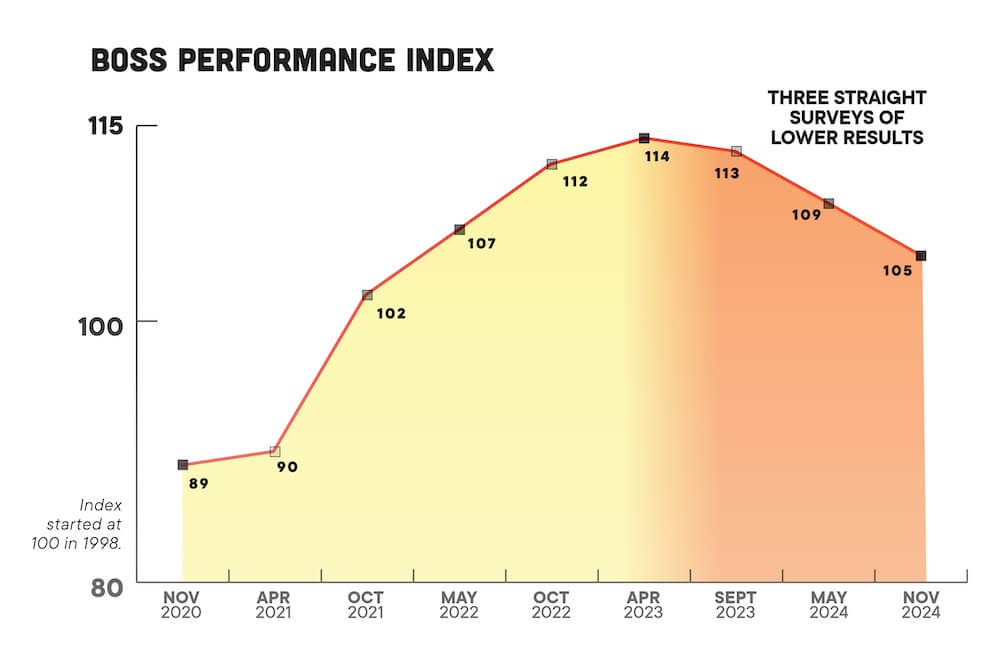

What a Sports Event Costs

At left and below are cost and revenue estimates for the Honolulu Triathlon International Festival of Sports, scheduled for May 19, 2013. Estimates are fixed costs based on 1,000 participants; a field of 800 is expected.

Costs

$38,800

Marketing and advertising, including signs, awards, T-shirts and logo items.

$22,403

Staff, including monetary donations to volunteer groups.

$73,053

Operations, including police, barricades/cones, ice, rentals, timing, tents, tables, chairs, insurance, permits and fees.

Total:

$134,256

(does not include Japanese staff and their costs).

Revenue

$135 entry fee x 800 participants =

$108,000

Profit/Loss

Cost of $134,256 minus revenue of $108,000 equals a loss of $26,256, which can be made up through sponsorships or more participants.

Source: JJ Johnson