Smart Path to Success

“Oh, no!” was Reuben Chong’s street name – as in “Oh, no! Here he comes!” For a decade, the homeless ex-convict prowled Honolulu’s Chinatown in search of money to support his drug habit. Who could imagine that this 34-year-old, street-smart thug would eventually find his footing at Leeward Community College, where he graduated as a straight-A student and student body president? He then went on to earn his bachelor’s and master’s degrees, again with honors, at UH Manoa.

Nothing in Reuben Chong’s life came easily. Given up by his parents at birth, he was abandoned by his adoptive parents at age 3. As a ward of the state, he shuttled between “at least a dozen” foster homes before fleeing an abusive “father” while in the 11th grade. After a precarious year on the streets, Chong joined the Army and stayed for almost six years. There, he completed high school, but also first tried drugs and alcohol. At 24, he mustered out with an honorable discharge. Broke and broken, with no family to call on, a demoralized Chong lived for 10 years on Honolulu’s mean streets or in shelters. He was convicted for four separate felonies for theft and assault, and served almost five years in prison. There, he began to turn his life around after a substance-abuse program.

“I wanted something, but I didn’t know what,” he told me over a pizza lunch. Delaying his release from prison almost a year, he entered a peer-counseling program, which stirred his interest in giving back to the community.

Chong found his place at Leeward Community College, an institution that embraced him when others turned him away. In 1998, he enrolled at Leeward. He had taken the standard battery of placement tests in reading, writing and math – but failed most. Steered into remedial courses and tutoring, Chong slowly assimilated. “But,” he says, “nothing I experienced in jail or on the streets intimidated me more than going to school, sitting in a classroom and competing with all those bright young faces.”

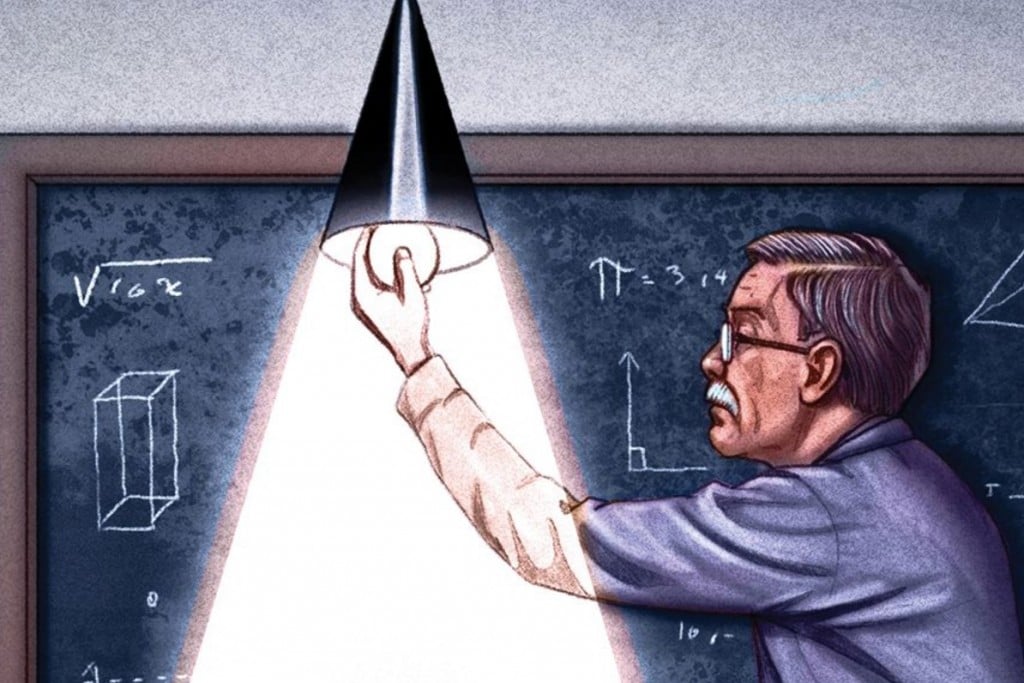

“You’re smart, you’re really smart!” Beth Kupper-Herr, director of Leeward’s Learning Resource Center, told him. “Those words of encouragement did it,” Chong recalls. “The lights came on, opening my eyes to my potential and the possibilities ahead.”

“I was so impressed by how driven he was,” Kupper-Herr recalls. Chong excelled in the classroom, tutored fellow students, served on a neighborhood board and made the mandatory visits to his parole officer. In his spare time, he read to the homeless in downtown Honolulu, counseled prison inmates and served as Leeward’s student body president. For his academic accomplishments, Chong was awarded a Presidential Scholarship at UH Manoa, where he graduated with honors, earning his BA and MSW degrees.

In recent years, he has taken on challenging counseling assignments for both the state and federal government. “That’s my gift,” he beams, “sharing my experiences, my hopes, with others. They may think I’m helping them, but I’m really the one who benefits.” Today, at 54, Chong serves as program manager for the nonprofit Community Health Outreach Work (CHOW) project to prevent HIV/AIDS.

“Leeward Community College opened so many doors for me, doors of dreams,” he says. “It changed my life.” Now, “Oh, no!” Chong is “Oh, yes!” Chong, helping others fulfill the American dream.

Community, or “junior,” colleges were created a century ago in America to provide open and affordable education in liberal arts and vocational training to a diverse group of nontraditional students, who, like Reuben Chong, could either enter the mainstream or fall back into a cycle of despair. Nationwide, these colleges serve almost half of all undergraduates, many of them juggling coursework with jobs and families. In many respects, these two-year, sub-baccalaureate institutions appeal to folks of all ages and backgrounds who can’t afford four-year colleges because they lack the required grades and/or funds, or are looking for practical courses that lead to a career. Yet to many, these hidden heroes, America’s community colleges, are derided as “schools of last resort.” (Leeward Community College – LCC – is often called “Last Chance College.”)

In academia, prestige remains the coin of the realm. At the top of the pyramid are elite schools such as the Ivies, Stanford, Duke and Northwestern. “At the bottom of the status hierarchy are community colleges,” says John Quiggin, author of “Zombie Economics.”

But community colleges are getting a re-appraisal. The price of four-year colleges has risen more than four times faster than inflation since 1978. And many Americans now question whether the high price is worth the lifetime earnings bump that, on average, comes with a bachelor’s degree. And easy student credit has turned steep tuitions and fees into a dangerous bubble, with student-loan debt hitting a record $1.1 trillion – more than America’s credit card debt.

Community colleges seem ideally positioned to meet these challenges. They have doubled in number nationwide since 1965, while their enrollments have exploded almost sevenfold over the same period. Though still serving as a stepping stone to a four-year degree, these hidden heroes do far more today than simply offer a ladder to the final two years of a university. Their mission has become more comprehensive, thanks to a gradual shift toward much-needed vocational education, job training and programs catering to the community. From crime scene investigators and video game animators to organic farmers and sustainability coordinators, cutting-edge two-year colleges provide a wide array of exciting career options. They also give 18-year-olds a glimpse into the world of work and, at the same time, prepare older people for a second or third career.

“I owe it all to community college,” says actor, producer, director Tom Hanks. He describes his stint at Chabot College in Hayward, California, as “the place that made me what I am today.” Chabot, in fact, inspired his 2011 film, “Larry Crowne.”

Community colleges offer low tuition (typically, a third less than a state university), convenient locations, open admissions and a broad spectrum of flexible courses in emerging fields where the number of jobs are growing. Add to this heavy remedial lifting, since at least half of their entering students require additional catch-up courses before diving into the regular curriculum, particularly those students whose primary language is not English.

They also suffer from an image problem. By often serving ill-prepared, economically hard-pressed students – the Reuben Chongs of the world, if you will – even the best two-year schools draw snickers from an increasingly cynical public.

“The bias against community colleges – and, by extension, their faculty members – runs deep in our society, and not just among academics,” reports Rob Jenkins, author of “Building a Career in America’s Community Colleges.” “I’ve encountered a surprising number of people, from all walks of life, who naturally assume that professors at two-year colleges must be second-rate intellects who couldn’t get a job at a ‘real’ college and whose ideas are, therefore, not worth considering.”

“Teaching is the ponderous portion of the profession, the burden to be carried,” according to Arthur M. Cohen and Florence B. Brawer, two longtime observers of the community college scene. Typically, the teaching load is non-negotiable; everyone teaches the same number of courses (usually three to five a semester).

No surprise then that some in academia consider the community college career choice “a loss of equity of their PhD training,” says professor Matthew Tuthill, a whip-smart molecular biologist at Kapiolani Community College. “At worst, they call it ‘career suicide.’ Some believe that junior college positions are for those who aren’t capable of competing in a traditional research setting.”

Having landed a job at one community college, SooJin Pate found faculty life far different from research-intensive University of Minnesota, where she received her doctorate. “The campus environment and the workload – teaching five writing-intensive courses each semester – created havoc on my body and spirit,” she recalls. “So I quit.” Another turnoff is the heavy dose of remedial courses that faculty must teach to help students advance to either a four-year institution or a career-oriented certificate.

There are also the so-called “dual enrollment” programs that require junior college faculty to descend into high schools to offer a host of courses. Conceived to accelerate the college experience and, hence, reduce student debt, these initiatives – financed largely by both private and public funds – allow 16- and 17-year-olds to earn dual credit and get on the higher ed track earlier, building up momentum toward a college degree ahead of schedule. Nevertheless, these dual-degree programs turn off faculty interested in serving a more mature clientele. Think “Sixteen Candles”!

Finally, don’t expect big bucks. Although community college professors have a much greater teaching load than their university counterparts, their salaries are considerably lower. Nationally, a full professor at a two-year school earns roughly the same as an assistant professor at a four-year institution, according to recent data from the American Association of University Professors.

Many community colleges are trying to improve their brand. In the past decade, some 40 colleges have gone so far as to drop “community” from their names. “Shedding the word ‘community’ is an important step toward attracting a broader cross-section of students,” argues Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation. But opponents view these efforts as “institutional aggrandization,” which compromise schools’ long-standing and carefully defined goal to serve the broader community.

“I’m against it,” says John Morton, who oversees UH’s vast community college system, now in its 50th year. . “Rebranding means straying away from our core mission of decades past to serve all members of the community. ‘Community’ is what defines us. It’s what makes us special.”

Insightful two-year colleges are attempting to better prepare their students for four-year university life. Kapiolani Community College students are discovering that high-level science is now an important career option. Kapiolani’s professor Tuthill works with two-year students to manufacture complex monoclonal antibody-producing hybridoma cell lines. To prepare for this work, students enroll in research-intensive molecular biology, tissue culture and protein chemistry-immunology courses.

“Not surprisingly,” says Tuthill, “research platforms like these enable our community college students to compete successfully with students from four-year schools at local and national scientific conferences. This work contradicts the dogma of the traditional role of community colleges and the reputations of their scientific staffs.” (According to the American Association of Community Colleges, nearly a quarter of science and engineering faculty members currently populating two-year campuses hold doctorates.)

Several miles away from Kapiolani’s picturesque campus on the slopes of Diamond Head, scholars at Honolulu Community College also are ramping up their 21st-century skills. The state Legislature recently allocated $38 million to build an Advanced Science and Training Center on campus. Leading the charge is HCC’s feisty chancellor, Erika Lacro. The 43-year-old high-flyer, with a doctorate in communications and information sciences, seems more like a hotshot CEO than an ivory-tower leader.

Back on the US Mainland, mathematics professor Robert A. Chaney, winner of an earlier Professor of the Year award, looks for practical applications of his discipline to motivate students at Sinclair Community College in Dayton, Ohio. Especially effective has been his robotics project, in which students write functions to program robots to walk or interpret data. “If students find early success,” he says, “they wind up enjoying math.” Administrative support to attend conferences and write grants, as well as the school’s state-of-the-art Math Science Technology Center, has helped Chaney’s hands-on approach to winning hearts and minds.

Ironically, faculty success in the hard sciences and liberal arts brings its own problems. Two-year college instructors, particularly those in the hands-on technical and vocational areas, are sometimes threatened by those committed to the more academic disciplines that dominate the university track. Striking the right balance between this cultural divide is a major challenge for community college leaders.

“It’s huge,” says the straight-talking Lacro. “The more practical, hard-trades faculty often take offense of their peers with advanced degrees, who, in turn, don’t want to be ‘dumbed down’ by those offering supposedly less rigorous coursework. What’s worse, students become aware of these tensions.

“As a result, I spend a good deal of my time bringing these two, often segregated, groups together,” she adds. “In many cases, I have to force a solution.”

Differences aside, I found both sides, and their leaders, committed to what one community college instructor called “an overpowering feeling of success.” For the most part, faculty accept that America’s two-year colleges are not selective, residential collegiate institutions. They know, too, that all higher education, at the end of the day, is career-oriented. “The poverty-proud scholar attending college for the joy of pure knowledge is about as common as the presidential candidate who was born in a log cabin,” argue Cohen and Brawer. “Both myths deserve decent burials.”

After years of flying under the radar, these hidden heroes of higher education are beginning to play to their strengths, putting quality education within reach of anyone willing to strive. “We are now out of the closet,” says Terry O’Banion, president emeritus of the community colleges’ League for Innovation. “This is an Andy Warhol moment.”

The ability to open doors and create opportunities for the Reuben Chongs of the world are enabling many community colleges to achieve their 15 minutes of fame. Nationwide, faculty turnover is low, and the desire to move to a flagship university, never great, is even less appealing. “I never thought I wanted to be anywhere else,” beams Sinclair’s award-winning professor Chaney. “I see my work making a difference in so many lives. Working here has truly been a dream come true.”

HIDDEN HEROES

This article is an abbreviated excerpt from the book “Hidden Heroes: Finding Success in the Shadows” By David Heenan, available from Watermark Publishing.