Our Kūpuna, Our Kuleana:

Senior Care Crisis in Hawaiʻi

The growing number of seniors is a personal challenge for hundreds of thousands of local families and a collective challenge for all of Hawai‘i.

IF you donʻt see this silver tsunami coming, you’re not paying attention,” says Jim Shon, president of the Kokua Council, an advocacy and empowerment group that focuses on seniors.

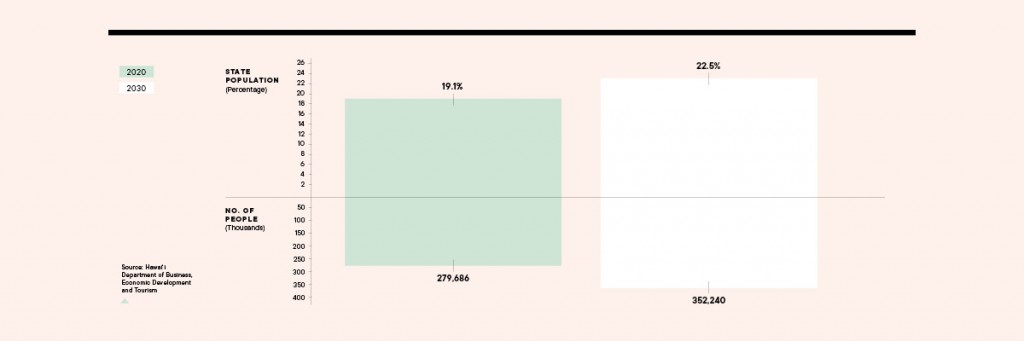

From 2020 to 2030, the percentage of people age 65 and older will go from 19.1% of the state’s population to 22.5%, according to the state Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism. The segment of people age 85 and older will rise to 3.6%.

Several people interviewed for this story say Hawai‘i and its people are not ready to meet the needs of the growing senior population. Many families are unable to afford the high cost of senior care, so the burden often falls on unpaid family caregivers, some of whom give up jobs to care for loved ones. Meanwhile, some of those who might be able to afford professional care might have a harder time finding it because Hawai‘i isn’t meeting the demand for long-term care workers such as certified nursing assistants, registered nurses, home health aides, case managers and drivers.

“We’re not prepared as a state to take care of our elderly. Most people are struggling on their own.”

▿

Clementina Ceria-Ulep

Long-term care committee chair

Faith Action for Community Equity

Senior care is an issue that will affect everyone either as a care recipient or as someone who’s trying to find care for a loved one, says Gary Simon of AARP Hawai‘i, the Hawai‘i Family Caregiver Coalition and the state Policy Advisory Board for Elder Affairs. “To look at Hawai‘i and not know anyone that has struggled with this, they must live in a bubble or be just isolated,” he says.

There are many businesses, organizations, and state and county programs that provide senior care, especially in home and community settings. Studies show that seniors who age at home tend to have better health, and the longer Hawai‘i can keep its seniors at home, the less taxpayers will pay for more costly facility-based care. Diane Terada of Catholic Charities Hawai‘i says Hawai‘i is doing well in its provision of care compared to other states, but it can do better. For instance, Hawai‘i’s complex senior care system, with differing eligibilities and costs, can be confusing and frustrating for elders and their caregivers to navigate, she says.

What’s needed, several experts agree, is more collective and personal action: more partnerships among community, government and families, and more planning by today’s workers for their own aging.

Out of Reach

The fact that so many people are living longer is a revolution says Margaret Perkinson, director of the UH Center on Aging. It requires that society rethink its

health care system, which traditionally has focused on short-term care, to address larger numbers of people living with chronic conditions.

Most people will need long-term care services and support at some point in their lives. Terada, administrator of Catholic Charities Hawai‘i’s community and senior services division, says it’s hard, however, to quantify the demand for senior care because much of it is hidden.

“A lot of the seniors for one thing are isolated and so we don’t necessarily always know about the people who need help until the situation becomes so dire that it becomes a public situation,” she says. “And same thing for the caregivers.” Her organization provides support services to about 4,000 seniors on O‘ahu.

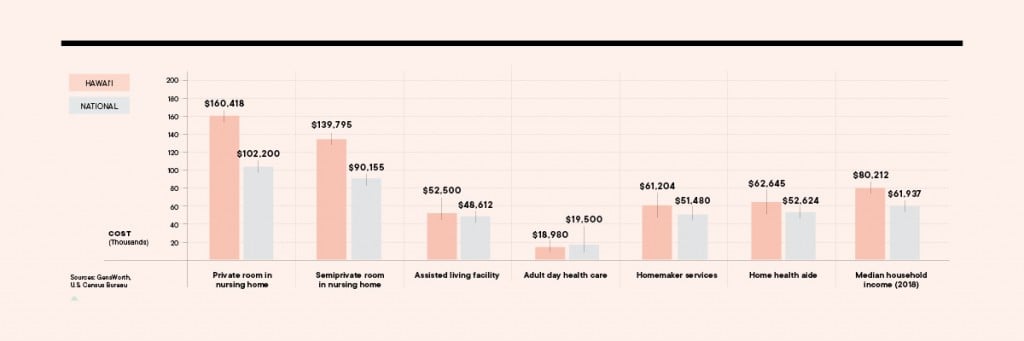

Many families can’t afford senior care. Having a professional caregiver come into the home can generally cost $23 to $25 an hour, says Clementina Ceria-Ulep of Faith Action for Community Equity, a grassroots interfaith nonprofit. And the median price for a private room in a nursing home exceeds $160,000 a year in Hawai‘i, according to GensWorth, a long-term care insurance company. In addition, long-term care insurance is expensive, and Medicare is limited and generally focuses on short-term stays in nursing facilities or requires that individuals be homebound. Medicaid will cover long-term care but people often have to impoverish themselves to qualify, says state Rep. Gregg Takayama.

These costs mean most senior care is provided in the home, Perkinson says. An estimated 157,000 unpaid family caregivers provide 131 million hours of care a year in Hawai‘i at a value of $2.1 billion, according to AARP Hawai‘i.

Typical family caregivers in Hawai‘i are women, likely to be married, over 55 years old and employed, and the average age of their care recipient is 80, according to AARP Hawai‘i. More than half of family caregivers report being stressed emotionally because of their caregiving responsibilities, about a third experienced health problems and more than a quarter felt financially strained.

Poki‘i Balaz, a geriatric nurse practitioner at the nonprofit Kokua Kalihi Valley, returned home to Hawai‘i in 2012 to care for her father, who has Alzheimer’s disease. Despite her medical background, she says, becoming a caregiver and the process of finding information and resources to assist her was overwhelming, stressful and physically and emotionally draining. She’s also had to stop working several times so she could care for her father.

“When you’re a caregiver … you’re the nurse, you’re the physician, you’re the lawyer, you’re the chauffeur, you’re the accountant,” she says. “You play all of these different roles that most people go to school and get a degree for, and you are expected as the caregiver to become all of that overnight and as the disease progresses.”

She is a support group facilitator and says some caregivers work multiple jobs and struggle with whether to buy food or pay their loved one’s medical bills; she’s been there herself. She says state programs that pay for housekeeping or in-house personal care for eligible kūpuna are helpful but can’t address all of the needs of seniors and caregivers.

Faith Action for Community Equity’s Ceria-Ulep says the state’s senior care programs need more funding. A 2-year-old state program called Kupuna Caregivers helps eligible working caregivers by covering the costs of services like adult day care, transportation, home-delivered meals, homemaker services, personal care and respite care. It received $1.5 million for the 2019-20 fiscal year, and caregivers are limited to $210 a week in services. That’s only enough to cover three days of adult day care or one day’s worth of professional caregiving at home, Ceria-Ulep says.

Another problem: The number of people who could potentially serve as caregivers is declining. In 2016, there were an average of about five potential family caregivers for every senior aged 80 or older; by 2030, the ratio will decline to 3 to 1.

“We’re not prepared as a state to take care of our elderly. Most people are struggling on their own,” Ceria-Ulep says.

How many older people need care?

“Community-dwelling” people are those who do not live in institutions or other group-living facilities. In 2017, 15,200 community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older in Hawai‘i had difficulty caring for themselves, says Hua Zan, an assistant researcher at the UH Center on the Family.

“Self-care difficulty” is defined as having a physical or mental health condition for at least six months that makes it difficult to take care of your personal needs, like bathing, dressing or getting around at home. She adds this estimate is low because it does not include older adults who have health conditions for less than six months but still need care for a time.

Not Enough Workers

As Hawaiʻi’s senior population grows so too does the demand for long-term care workers – everyone from certified nursing assistants to home health aides to drivers and case managers. But growing this workforce is difficult.

Kathy Wyatt of Hale Hau‘oli Hawai‘i, an adult day care center in ‘Aiea, says she hasn’t had challenges filling positions at her center, but other centers, nursing homes and home care agencies are “screaming for help.” A 2019 Healthcare Association of Hawaii survey found that healthcare providers had 417 open positions for certified nursing assistants, clinical assistants and nurse aides, 51 open positions for home health aides, 35 open positions for personal care assistants, and 463 open positions for registered nurses.

Several sources agree that low pay is a big barrier to attracting more workers. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median hourly wage for home health aides in Hawai‘i was $12.69 in May 2018; for nursing assistants, $16.76. If their salaries were raised, Takayama says, those costs would get passed onto seniors and their families.

“We’ve been saying silver tsunami for decades. It is here in Hawaiʻi.”

▿

Cyndi Osajima

Executive Director

Project Dana

Some positions, like certified nurse assistants, are physically demanding, Ceria-Ulep says, because these workers feed, bathe and dress patients, get them ready for appointments and, if they’re bedridden, turn them every couple of hours. Some workers burn out and leave for less physically demanding and higher paying jobs in other industries.

Several organizations have launched certified nurse assistant training programs to create more workers. Wyatt launched her Hoaloha Nurse Aide Training Program last year and has graduated 19 students. Retirement community Kāhala Nui recently launched its CNA Training Academy of Hawai‘i, and Faith Action for Community Equity will contract with an outside vendor to provide training.

“We feel that even if we train somebody and they don’t work for us, it’s still helping the community, because we’re bringing more people into that area,” Kāhala Nui President and CEO Pat Duarte says.

However, offering training may not be enough. Ceria-Ulep says when Faith Action announced it would train two cohorts of CNAs in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the response was immediate. This time there was much less interest. “I don’t know if it’s because we have such a low unemployment rate and a lot of people have job options, but it’s hard to attract people into it,” she says.

“If we don’t address this workforce issue, even if we have money, there will be no care because there’s no one to provide the care. That’s the reason why we need to pay attention.”

Progressive State

In its first year, the Kupuna Caregivers program assisted 110 caregivers who cared for 112 kūpuna. The state also provides home- and community-based supports to eligible seniors using state and federal funds, says Caroline Cadirao, director of the state Executive Office on Aging. In the 2018-19 fiscal year, the state provided services to 8,878 seniors age 60 and older. Federal funds also provided 463 caregivers of older adults with counseling, support groups and training, 278 caregivers with respite care and 254 caregivers with supplemental services like home-delivered meals, assisted technology and

home modifications.

Takayama says the Legislature’s provision of $11 million in funding for kūpuna-related programs for fiscal year 2019-20 is recognition of the growing need because people live longer here. Hawai‘i residents born in 2016 have an average life expectancy of 81.3 years, compared to a U.S. average of 78.6. He says Hawai‘i is known for a caring attitude toward its seniors.

“I think all in all, Hawai‘i has lived up to the idea that nobody gets left behind,” he says. “And it’s more than a political philosophy. I think it’s more of a recognition that here in Hawai‘i we all take care of each other.”

He also says these government programs are common sense: The state and taxpayers save money when seniors are cared for at home rather than in nursing homes.

Kūpuna and their caregivers can also turn to nongovernment organizations for support. Kāhala Nui in 2015 opened its LiveWell at Iwilei adult day care center to provide a cost-effective way to help seniors age at home. Day care services typically cost $70 to $75 a day compared to $200 a day for a professional one-on-one caregiver, Kāhala Nui’s Duarte says.

In recognition of the increasing number of people living with Alzheimer’s or related dementias, organizations like Catholic Charities Hawai‘i, the UH Center on Aging, the Alzheimer’s Association Aloha Chapter and the Executive Office on Aging are building awareness and training caregivers. The City and County of Honolulu has committed to becoming an age-friendly city that develops programs, services and projects that are designed to accommodate people of all ages. Hawai‘i also has a Dementia Friends initiative to spread awareness and encourage people to be kind and supportive of individuals with dementia and a Healthy Aging Partnership state program that encourages active and healthy aging through exercise programs and chronic disease education.

Volunteer efforts help fill in some gaps in services, says Cyndi Osajima, executive director of Project Dana, a volunteer-based Kupuna Care service provider that serves about 1,200 seniors a year. But there will always be a limit to what volunteers can provide, Catholic Charities Hawai‘i’s Terada says: “The demand for this type of care is tremendous.”

Cost of Aging

Here are the 2019 annual median costs for senior care in Hawaiʻi vs. the national median.

Planning Ahead

Balaz, the geriatric nurse practitioner at Kokua Kalihi Valley, says senior care is a multigenerational problem.

“There’s people like me who are in the prime of their professional years and are having to make a choice between that or being a caregiver, which makes me feel guilty every day,”

she says.

Kealoha Takahashi, executive of Kaua‘i County’s Agency on Elderly Affairs and a board member of the National Association of Area Agencies on Aging, says working Baby Boomers need to start planning for what their lives will look like 10, 20 years from now.

“We’re trying now to educate as many as we can, especially on caregiving issues. … We know it’s coming, but we just have to take small steps at a time,” she says.

AARP Hawai‘i advocated in the 2019 legislative session for the creation of a state retirement savings program for private sector employees. Modeled after OregonSaves, workers would contribute to the retirement fund through payroll deductions and a private company would invest the money in traditional financial products. The bill, which would have specially benefited workers at small businesses that don’t have 401(k) programs to offer their employees, did not pass.

Keali‘i Lopez, AARP’s Hawai‘i director, says she hopes the state Legislature will reconsider the program because it would create an effective way for such small businesses to offer their employees an individual retirement program. “We’re concerned that a lot of young people just haven’t considered the fact that they’re going to need resources – and their family is going to need it – for when they retire,” she says.

Betty, left, and Honest are both 83. Her heart issues make it difficult to walk long distances and she doesn’t drive, so Project Dana volunteers like Honest drive her to the grocery store and library. | Photo courtesy of Project Dana

Ceria-Ulep says the community also needs legislation that supports family caregivers. In previous years, Faith Action for Community Equity unsuccessfully advocated for the creation of a state long-term care insurance program that would provide a sustainable funding source to help caregivers care for their family members. The state Legislative Reference Bureau recently published a study on the impacts that creating a paid family leave program would have on employers, caregivers and industry. Click here to see the study.

“Until you’re caught in the situation of having to care for your own elderly, or until you do your own caregiving, I think people can’t relate to the need,” Ceria-Ulep says. “But it’s something that’s catching up with all of us.”

Osajima says the community needs to change its mindset and ramp up support for the aging population.

“We’ve been saying silver tsunami for decades. It is here in Hawai‘i.”

Read the other parts of this story:

▹ Snapshot of Hawaiʻi’s Family Caregivers

▹ How to Plan for Your Life as a Retired Senior