Rent Control: Step Right Up!

Move into this 917-square-foot, one-bedroom apartment in a lovely, remodeled historical building. Washer/dryer, balcony, air conditioning all included for $875 a month. Just one problem, Island dwellers. It’s in Cleveland. For a similar cozy vibe in Honolulu, you’ll pay at least $2,649, according to Expatisan’s cost-of-living index.

Last year, 10,000 more people left Hawaii for the Mainland than moved in, according to the U.S. Census. The high cost of housing is certainly one factor driving residents to lower-cost states such as Washington and Nevada. However, the demand for affordable rentals far outstrips supply in many places in the country, not just Hawaii. A National Low Income Housing Coalition study found that, in 2014, there were only 57 affordable and available rental units for every 100 very low-income renters.

At every price point, rentals are getting harder to come by, because more people are renting nationwide – 36.4 percent of households – than at any other time since the 1960s. Hawaii’s people are hardly alone in struggling to put roofs over their heads, though it’s a particularly egregious challenge here.

That’s why, in January, state Rep. Kaniela Ing introduced House Bill 1267, which would require the Hawaii Housing Finance and Development Corp. and each county to launch a pilot project to explore rent-controlled housing. Ing serves the 11th House District of South Maui, including Kihei, Wailea and Makena. His goal is to “encourage the construction of new rental housing in the state that is affordable to low-income tenants and to evaluate the impact of rent controls on the housing market of the state.” The pilot project would run through 2023.

The HHFDC opposed the bill. Executive director Craig Hirai’s statement said, “Studies have shown that rent control is an ineffective and often counterproductive housing policy.”

The bill was also opposed by the Hawaii Association of Realtors. Myoung Oh, director of government affairs, provided a statement that read, “Unless a rent-control law permits a fair rate of return over time, landlords (including landlords of affordable rentals) may not be able to maintain their units. For example, one problem resulting from an inadequate rate of return over time is the backlog of deferred maintenance.”

The measure passed its first reading and was deferred. It’s likely to be reintroduced next session. Ing says the bill was “the right thing to do. I figured it would create a catalyst.” He prefers it the other way around – to have a bill follow a movement – but, noting the lack of strong tenants’ groups in Hawaii, unlike in places such as New York City, he felt he had to act.

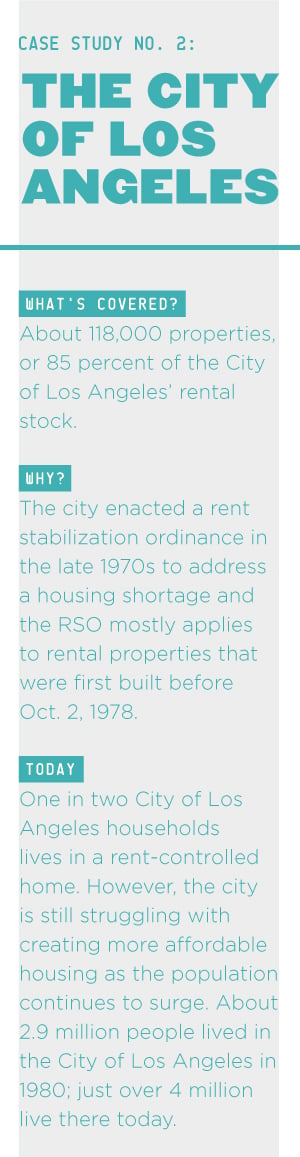

“If you want to rent a room, just a room – no view, inside a house –in my district, it’s $900 to $1,000 a month, and salaries have stagnated over the past 30 years,” Ing says. “I’ve looked at rent stabilization policies in Portland, San Francisco and on the East Coast, and they aren’t as controversial as the 1970s-style rent control was. It blew my mind that, as a Legislature, we haven’t looked at rent stabilization in earnest in 15 years. Most rent-control programs are born out of a crisis, and that’s where we are in Hawaii.”

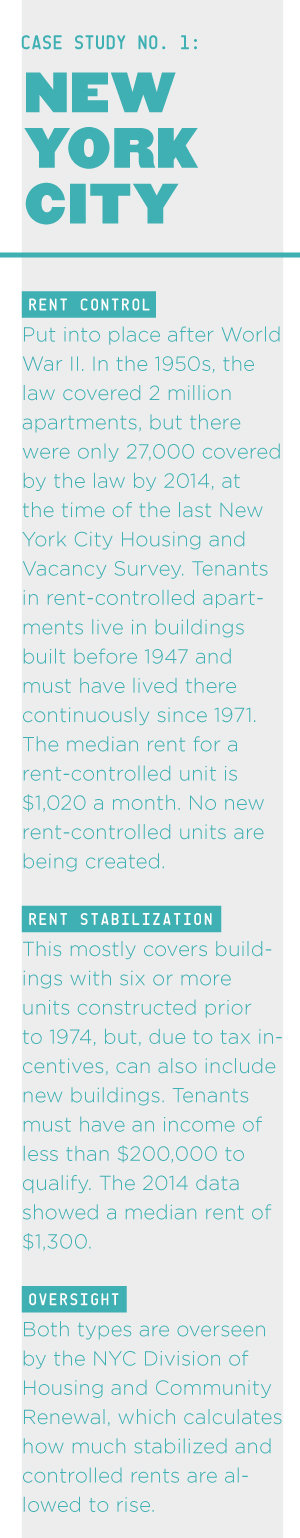

Four states – California, Maryland, New Jersey and New York – as well as Washington, D.C., have rent-stabilization laws. Would they make sense in Hawaii?

THE CONS

Opponents of rent control say it would only make a bad situation wors, and that the real solution is to relax the rules that inhibit the construction of new homes. Photo by Aaron K. Yoshino.

“Rent stabilization may look nice on paper, but it often results in less housing options for the poor,” says Kelii Akina, president of the Grassroot Institute of Hawaii. The organization produced a report, “Using Disparate Impact to Restore Housing Affordability and Property Rights,” focusing on Hawaii’s strict land-use laws and how they have affected its housing supply.

“Of course, it’s politically popular in high-cost areas to mandate lower rents,” says Akina. “But many in Hawaii may have learned a lesson from the unintended consequences of controlling rents on the Mainland. When New York City implemented tough rent-control policies during the 1970s and 1980s, over 300,000 apartments were abandoned over an 11-year period. In San Francisco, 30,000 rent-controlled units that have fallen into disrepair now sit vacant and abandoned. The best way to relieve housing and rent prices is to allow home builders the right to build on their own land.”

Economist Paul Brewbaker, principal at TZ Economics and a lecturer at UH Manoa, says the solution is to “build more housing, way more housing, any kind of housing, multiples of how much is being built today.”

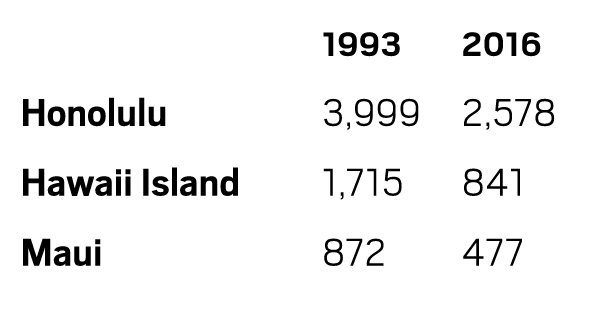

The supply of new housing in Hawaii is far below the growing demand. Here’s a comparison between housing units authorized by building permits issued by the counties in 1993 and last year:

Brewbaker also notes that, in the discussion of rent stabilization, two of society’s problems are being conflated: insufficient housing and insufficient wages.

“Pay increase taps into things like human-capital formation, educational opportunities, even early childhood development, things which are hugely overlooked. The research shows that, if you invest in cognitive development early on, it creates more opportunities for lower-skill workers to acquire the skills necessary to live on.”

“Pay increase taps into things like human-capital formation, educational opportunities, even early childhood development, things which are hugely overlooked. The research shows that, if you invest in cognitive development early on, it creates more opportunities for lower-skill workers to acquire the skills necessary to live on.”

On the insufficient-housing side, he says, the state Legislature has only itself to blame. Brewbaker gives the redevelopment of Kakaako as an example. “The state took over the allocation and development of allocation of Kakaako. The state intervention imposes an affordable-housing requirement in a high-density area, the working center for Downtown and Waikiki, and it has the unintentional consequence that only luxury developers can make it pencil out. Because the infrastructure is so much more complicated in the urban areas than out in an old sugar field, where you stick a pipe in it. But, building out in Central or West Oahu doesn’t really make sense. Once you have the hour commute to get to Downtown or Ala Moana, it’s not worth it. Honolulu needs to realize that it’s a real city after 50 years of statehood – a real city. Let’s make it work. That dream of the car and the house in the suburbs is about 30 years gone. Development should be focused on folding back on the urban core, expanding mass transit and renewing the urban development.”

If he were to do it, Brewbaker says, “I’d find five or more areas near every train station. Have the rule be, ‘Knock yourself out.’ Build whatever you want by the Waipahu train station. I’m pretty sure the rich people won’t live near the Waipahu train station, but there are people who will.” Create affordable housing solutions there, he suggests, and a clinic, and a park-and-ride. “But there’s the dilemma. Because, politically, it’s very hard for legislatures to do that. They would be doing something different from what you’ve already been doing for 30 years. I respect the fact that the Legislature is looking at ideas, but, at the end of the day, it should be about enabling the delivery of more units. Then you don’t need to control anything.”

THE PROS

“It’s unfortunate that the dominant American culture is to view homes primarily as a commodity – an investment or a business – and so it takes people who want something different, who want to prioritize everyone living in a home rather than extracting profit from a home, a lot of energy to push back against that,” says Aimee Inglis, associate director of San Francisco-based Tenants Together, California’s only statewide renters’ rights organization.

“The crisis of displacement is so bad that we’re seeing a similar groundswell of support for policies like rent control that we also saw in the 1970s,” she says. “At that time, the crisis had a lot to do with out-of-control inflation; today, the roots of the crisis are the speculation on land and housing – more and more corporations buying up homes and raising the rents. It is always a good time for rent control, because it is basic fairness to limit annual increases so they don’t spiral out of control, and to require landlords to give a valid reason for eviction. People are able to get more political support for the policy now in California because the crisis is so acute that even upper-middle-class people feel they need basic renter protections like rent control.

“It is a common mistake to view this as merely a neutral policy discussion,” says Inglis. Because, on one side, there are landlords, real estate agents and developers who have a “direct profit motive, and the other side is just trying to stay in their homes, raise their families, and contribute to their communities. Without rent control, more are driven into homelessness and vulnerable populations like seniors and people with disabilities face clear adverse health effects related to eviction and displacement. These talking points about ‘rent control deterring new construction’ are economic theories that don’t bear out in reality. California has over a dozen cities with rent control – those cities have been among the leaders in building new housing.

This particular argument is a straw man because most every new rent-control law exempts new construction from being covered.”

WILL TENANTS UNITE IN HAWAII?

WILL TENANTS UNITE IN HAWAII?

Melissa Estrella is a working professional and mother who lives on Hawaii Island. She put up a page on Facebook called YesHIRentControl, in support of rent-control laws, because, “Our family is a two-income family and the rent is still so outrageous.” A Puna resident, Estrella says she noticed the rents skyrocketing after the lava scare in 2014-2015. She also sees a lot of homes turned into vacation rentals. Concerned over high rents and issues of homelessness, she created the Facebook page and reached out to her state representative, Joy San Buenaventura, asking for support on rent control.

“The cost of living is so high on the Big Island,” Estrella says. “I came from the Mainland, where the rent was high but the cost of food was low. Here the food is high and the rent is high. You’re either going to starve or become homeless. Building more units might be a solution, but not if they are going to charge exorbitant rates. Families with children are really scared.”

Rep. Ing says rent stabilization is the type of issue that can’t be driven through the Legislature. It needs grassroots support. Will Hawaii’s renters coalesce into tenant associations? As Inglis notes, tenants would need to “decide what they want to do to address the problem of rising rents, but people do not live single-issue lives and this fight is one of many fronts where people are trying to have control of their communities.” With rents continuing to rocket up in Hawaii and the new bill being introduced, rent control is a cause that may catch fire in people’s imaginations.

OTHER OPTIONS

Short of rent-control laws, what are other ways the state could make housing more affordable? Here are some ideas from Gavin Thornton, executive director of the nonprofit Hawaii Appleseed Center for Law and Economic Justice, which advocates on behalf of low-income individuals and families in Hawaii and conducts research on community issues, including housing.

Subsidies for affordable housing. “That’s absolutely critical. The governor has proposed amounts to fund this, but it was cut by the state House and Senate, and revenue has not been as high as forecast. Last year, we think there were record levels for funding affordable housing and this year, there are signals it will be significantly less.”

Transit-oriented development on Oahu. “You can build higher because you need less parking spaces, and parking is really expensive. Make sure the community gets back their investment in rail.”

Accessory Dwelling Units. An ADU is a small rental property with a full kitchen, bathroom and sleeping area. “Homeowners can contribute to solving the affordable housing crisis. They can build a unit on their property, or one attached to their house. We did a paper on this and got legislation passed to make ADUs legal.” It also creates income for the homeowner, so it’s a win-win.