Rehab Hospital of the Pacific Reinvents Itself

Restoration is a slow and sometimes painful process for people whose bodies have been battered by strokes, car crashes and other calamities. Helping those people regain their basic skills and abilities is the main goal of the Rehabilitation Hospital of the Pacific.

Sometimes the challenges are almost impossible for the rest of us to comprehend.

“I was chatting with a physical therapist at an awards luncheon recently and asked her what she’d been up to,” says John Komeiji. “She told me, ‘I’m taking some classes so I can better teach people how to swallow.’ I literally put my fork down and asked, ‘How do you do that?’”

Komeiji is Hawaiian Telcom’s senior VP and general counsel and he’s also been chairman of Rehab Hospital’s board since 2007. That means he’s witnessing a transformation at the hospital that mirrors the changes taking place at every healthcare provider in Hawaii – big and small. In some ways, that healthcare transformation parallels the changes forced onto rehab patients, who must learn new ways of doing old things in order to survive and thrive. In both cases, it also means using new technology and new processes to do things they have never done before.

“We have patients who haven’t been able to stand up in 20 years put on our Ekso Bionic Suit, which allows them to stand,” says Dan Uyeunten, director of Rehab’s Robison Family Innovation Center. “They just stand there and look around and say, ‘This is the first time I can look someone in the eye standing up.’ ”

Wendee Waki, a Rehab occupational therapist, works with patient Jean Mitsukawa.

Leading the transformation at the 60-year-old nonprofit hospital is CEO and president Dr. Timothy Roe, who took the job on Jan. 21 of this year. Roe says there’s no doubt that healthcare across America needs to be fixed, regardless of whether the federal Affordable Care Act happens or not. He repeats that mantra daily to his team.

“Everyone involved in healthcare has been surprised by the pace at which these changes are taking place,” says Roe, 52. “I think it’s really driven by the understanding that the cost of healthcare in the U.S. has been very high. In the past, there hasn’t been a clear linkage between healthcare expenditures and the benefits received from services in terms of quality and outcomes.”

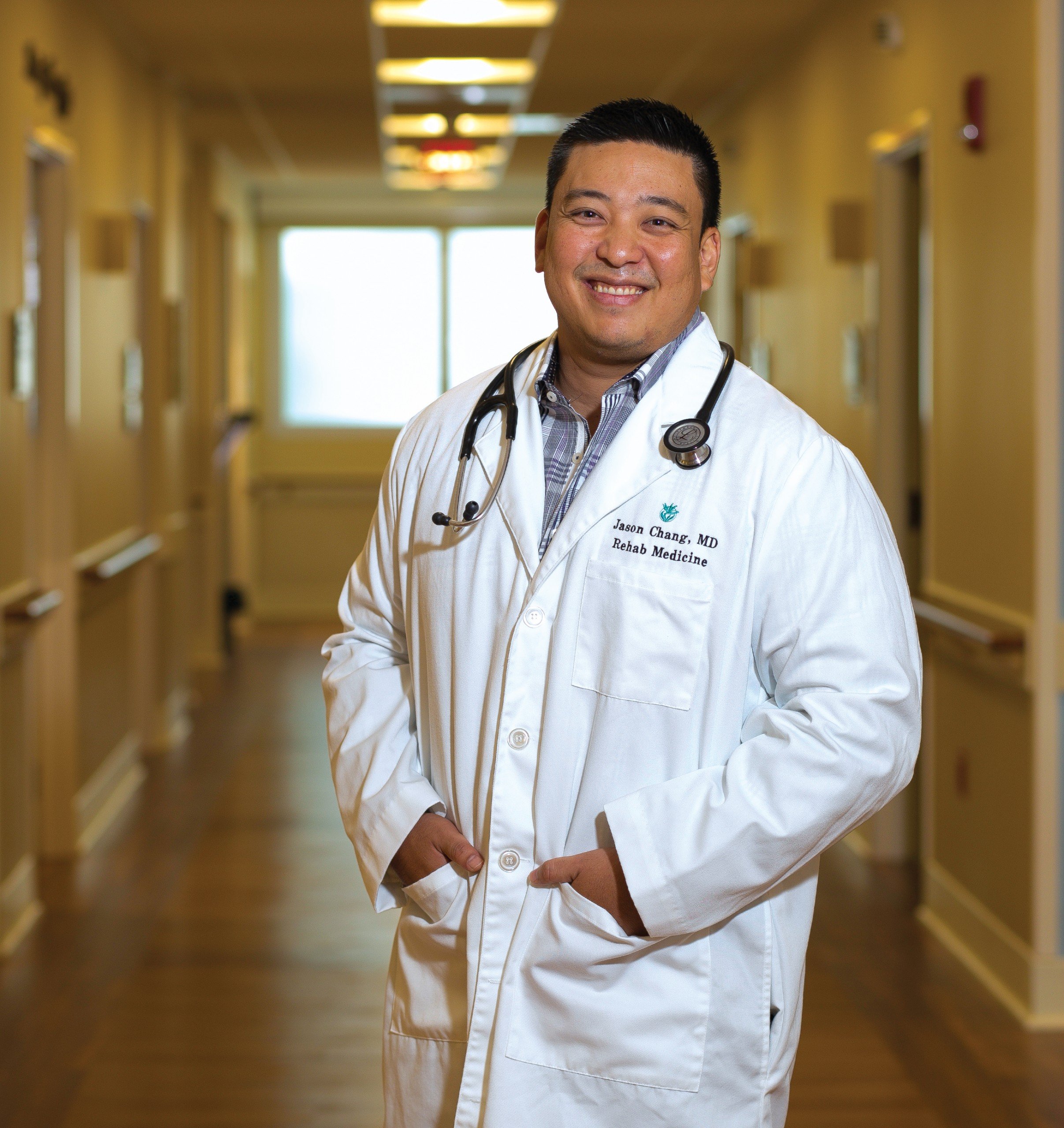

Rehab’s medical director, Dr. Jason Chang, says one key thing that must change is the attitude of physicians.

The medical director, Dr. Jason Chang

“We joke that doctors are terrible business people. They don’t teach you this in medical school or residency,” Chang explains. “But the reality is, we need to acknowledge that financial matters, business and marketing are part of the new way of practicing medicine. We need to adapt to change.”

Whether Rehab Hospital succeeds is important to everyone in Hawaii because it is the only acute-care rehabilitation hospital serving the state and much of the Pacific. That means it provides short-term care for many of the most challenging physical therapy cases.

Since Roe took over, Rehab says it has intensified efforts to change the way it operates.

“Despite all the ‘political hurrah’ about the Affordable Care Act, the underlying changes are going to happen no matter what,” Roe says. “So that’s what I’ve told my staff to prepare for. Every day they pick up the paper and see something about ObamaCare. Is it going to be overruled, voted in or voted out? I tell them the changes are bigger than that. These are fundamental reforms in the healthcare system and we need to be able to adapt.”

Robison Innovation Center

One of those reforms concerns the effectiveness and quality of service. In the past, a service would be provided to a patient and Medicare would pay the bill, regardless of whether the service was effective, done well or efficiently.

But Roe says there was a lot of dissatisfaction with the outcomes under that system, so there’s a movement now toward “patient-centered care” – focusing on what’s best for the patient rather than what the healthcare provider wants to do. That’s a big challenge in any healthcare market, and it manifests itself in ways big and small.

One way is understanding how pieces of the overall healthcare system fit together. Chang says Rehab needs to get the word out to physicians in the community that Rehab can play an important role in their patients’ treatment. He says many healthcare providers don’t understand how Rehab fits into the overall patient care plan.

“I would say in the past, physicians might have been hesitant about referring patients here,” says Chang. “It’s a struggle to make our acute-care partners aware of who we are, what we do and which patients to send to us.”

In fiscal year 2012, Rehab provided 1,330 patients with comprehensive care at its hospital and served 4,736 patients at its three outpatient clinics in Nuuanu, Aiea and Hilo, according to Rehab’s latest annual report. Chang says the hospital must follow a lot of regulations governing those patients.

“Now there are regulations as far as percentages of patients with certain diagnoses and requirements as to how sick they need to be,” he explains. “The regulations are very strict for us. Our patients must have a minimum three hours of therapy a day, five days a week.”

One major change at Rehab, says Chang, is the type of patients the hospital now helps.

“In the past, we served mostly patients seeking elective treatment such as hip or knee replacements, so they tended to be healthier. The hospital would be completely full, and off they’d (patients) go after their procedures and they wouldn’t come back.”

Today, 46 percent of Rehab’s clients are stroke, brain or spinal cord-injury patients. Nonetheless, the hospital says it still boasts one of the highest “discharged-to-community” rates in the country, at 85 percent. The national average is 76.4 percent, according to the 2013 Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation.

It’s a feather in Rehab’s cap, but Roe says he is aggressively putting systems and programs in place to raise the bar. To do that, Rehab is adopting best practices from the nation’s top hospitals.

“There’s a real push that providers need to integrate. Part of that is being driven by examples set by very large, integrated healthcare systems, like the Mayo Clinic, where thousands of physicians see a million patients a year,” explains Roe. “They’re able to provide everything the patient needs from the moment they walk through the ER door until the time their condition is resolved. That’s the model being used. But how do we rise to that model? Not everyone has the resources of the Mayo Clinic, but, at the same time, we need to provide a similar level of quality and value to our patients as the Mayo Clinic does.”

One of Mayo’s innovations in the early 1900s was the integrated medical record. The system initially used wheeled wicker baskets that usually ran along overhead cables. The basket would carry patients’ medical records and follow the patients as they moved through the clinic. Starting in the 1940s, the system used underground pneumatic tubes. Those systems were primitive compared to modern digital records, but they all shared the same goal: one medical record and one source of information for each patient.

“Having integrated medical records with one source is beneficial to the patients and that’s what we’re trying to get to now. The goal is for every provider and hospital to be hooked together,” explains Roe. “But it’s not that simple since there are a lot of issues involved, privacy laws including HIPAA (the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) and challenges due to potential computer hackers.”

Roe says the unexpected closure of Hawaii Medical Center West in 2011 showed how gaps in information can disrupt patient care because other facilities could not immediately access HMC’s records. He says everyone in the healthcare community should work toward a secure healthcare information exchange, including the state, hospitals and physicians.

Since taking over at Rehab, Roe has introduced the Community Liaison Service, which is modeled after a program at the University of Texas’ MD Anderson Cancer Center. Community liaisons are registered nurses or physical therapists stationed at area hospitals who educate, promote and create awareness of Rehab’s services to providers and patients. It is an example of how healthcare organizations today must market their services.

Something else Roe has introduced is the Care Coordination Program, which is modeled after several mainland programs, including the Colorado Children’s Healthcare Access Program. Care coordinators, who are either RNs or social workers, work internally at Rehab to make sure patients have access to resources. They are a part of the patient’s healthcare team and make sure everything that needs to be done for the patient gets done.

“One of the first things I told my staff is that I subscribe to the philosophy of Steve Jobs in that I am always shameless in stealing great ideas,” says Roe. “We scan the country for good ideas, keeping our eyes open. We don’t want to reinvent the wheel if we don’t need to.”

Board chairman Komeiji says Roe’s leadership has helped the hospital restructure and become more market driven.

“A lot of effort moving forward is in education and outreach. One of the reasons we chose Dr. Roe is he is a physician – a physiatrist – with an MBA,” says Komeiji. (A physiatrist is a doctor specializing in physical medicine and rehabilitation.) “Having a CEO who is also a doctor is huge when it comes to credibility in the medical community. He also managed mainland hospitals and worked for a large hospital system that had programs and processes that were tried and tested. He brings a systematic approach to things. He’s different from previous leadership in that he brings a lot more experience in the physical-therapy/rehab-hospital arena than we have ever had in the past.”

Along with the program changes, there are major changes in the hospital itself. The current building was constructed in 1957 to replace the original “facility,” a Quonset hut. The structure was considered modern at the time, but has undergone little change in its 56 years.

A $17.2 million capital campaign for a complete renovation was launched in June 2011 and construction began two months later. The project is on track for completion next March. In addition to complete floor and room renovations, upgrades include the addition of family rooms, healing gardens, transitional apartment rooms, special-ized patient rooms and other enhancements to improve patient safety and comfort.

From the warm, earthy tones to the multipurpose rooms with views, the modernized building is a stark contrast to the sterile, clinical atmosphere of the past six decades.

“I think the renovation helps patient morale as well as employee morale,” says Komeiji. “You think about being in a hospital that came out of the 1950s as opposed to a modern-looking one. Just the ability to look out the window at a view can make people feel better.”

Despite the previous clinical atmosphere, Komeiji says, he frequently hears positive comments from patients.

“I find the first thing that patients talk about is the quality of the staff, so they could look beyond the bad-looking facility. Of course, first impressions aren’t everything, but they’re a whole lot. If I come to a junky facility, my staff has to work extra hard to overcome that perception.”

Komeiji says the pressures of healthcare reform play a role in the hospital’s changes, but the most important driver is something else.

“It’s about what kind of care do the people of Hawaii deserve and expect? If you’re really rich and you have a stroke, you can go to Craig Hospital in Denver, which is considered the stroke hospital,” explains Komeiji. “So the idea is to provide the highest level of care that we possibly can within our fiscal restraints. Government regulations complicate things since they determine which patients we can see. So we have to keep on running faster to keep up with change.”

Roe anticipates that the 2013 fiscal year will show the first growth in net patient service revenues in five years.

“The environment for rehabilitation hospitals has been difficult in the last few years due to reimbursement cuts and the Medicare restrictions on the types of patients we can admit,” explains Roe. “Rehab’s net patient-service revenues fell nearly 20 percent between 2008 and 2012. Donor support and other nonoperating revenues have made up for much of the decline, but it’s clear we need to focus on operating in an effective and efficient manner.”

The Medicare cap restriction of $1,880 annually per patient for outpatient physical therapy is frustrating, Chang says.

“If you go beyond the cap, the patient pays for it, or our foundation can provide charity care, but there’s only so much to go around and how do you decide who to help?” asks Chang. “There’s no clear path. How do you balance taking care of people with limited resources and laws in place to make sure we are all held to a certain standard?”

The hospital’s foundation is vital in keeping the hospital moving forward. Its 2012 annual report shows $3.08 million in donor support. Just under $500,000 of total giving was used to purchase patient-care equipment. The hospital made a commitment to offer state-of-the art technology in the opening of its Robison Family Innovation Center in 2011.

It has invested in three technologies: the Ekso Bionic Suit, Alter-G Antigravity Treadmill and the Alter-G Bionic Leg.

Uyeunten credits his predecessor, former center executive director Teresa Wong, for changing the direction of the clinic. Wong left Rehab in December 2012 to become VP of clinical development for Vasper, an alternative fitness program.

“Teresa revolutionized the hospital’s vision by showing us that we hadn’t really changed a whole lot since the 1980s in our facility, our look and the attitude in how we treat,” says Uyeunten. “We were using elastic bands, hands-on therapy and weight machines, and we still use those, but Teresa told me there’s no reason, just because we’re stuck in the middle of the ocean, we can’t have the same technology as the mainland facilities.”

Komeiji says launching the Innovation Center took strategic planning.

“In many organizations, if you’re innovative, the force of the organization, the bureaucracy, can shut down innovative ideas. That’s why a lot of the big companies are not the biggest innovators,” Komeiji explains. “So the idea was to create a separate unit to start incubating some of these ideas. But at some point you need to reintegrate these innovations into the mainstream.”

Rehab is now one of only 11 hospitals in the country using the Alter-G Bionic leg, a robotic leg used in therapy that allows patients to sit or stand. The Ekso Bionic Suit, or exoskeleton, enables patients with lower extremity paralysis to stand up and walk during therapy.

Uyeunten believes the state-of-the-art technology has put Hawaii on the map in the national rehabilitation community and he gets frequent inquiries from other facilities, including a recent visit from a vacationing doctor, Geoffrey Ling, deputy director of the Defense Advance Research Projects Agency. Ling is a brain and spinal cord specialist, who wanted to acquire the technology for Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

“Sometimes, we in Hawaii undersell our abilities,” says Komeiji. “I want to get us to where we feel there’s no need to go to the mainland for treatment. We can get the level of care that we could get anywhere else in the world, right here.”

The Birth and Life of Rehab Hospital

March 1953 Oahu Health Council invites Dr. Howard Rusk, considered the founder of rehabilitative medicine, to Hawaii to survey the state’s needs.

June 1953 Kauikeolani Children’s Hospital approves plans to establish the Rehabilitation Center of the Pacific primarily to serve polio patients.

Sept. 1953 Rehab opens in two Quonset huts in the back of the children’s hospital with 18 inpatient beds.

May 1956 Plans approved to construct new facility.

June 1957 Rehab opens new building with state-of-the-art pool.

October 1969 The center changes its name to the Pacific Institute of Rehabilitation.

October 1975 The center separates from the Kauikeolani Children’s Hospital and becomes an independent nonprofit and the name changes to Rehabilitation Hospital of the Pacific. (Sidenote: Kauikeolani Children’s Hospital merged with Kapiolani Hospital in 1978 to become Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children.)

Mid-1980s Rehab begins opening outpatient therapy clinics across the state.

2005-2010 New programs include one blending modern Western treatments and traditional Eastern ones, and another that includes vehicle modifications and helps people drive again. Other new programs focus on women’s health, clinical pilates and aquatic therapy.

June 2011 Launches capital campaign to raise $17.2 million for hospital renovation.

August 2011 Renovation construction begins.

December 2011 Innovation Center opens.

2012 Cardiac Health Program launches.

2013 Rehab celebrates 60th anniversary.

Where Rehab Spent Its Donations

Rehabilitation Hospital of the Pacific Foundation received $3,078,815 in donations during fiscal 2012. Here’s how it spent the money:

Rehab’s Patients

Rehabilitation Hospital of the Pacific and its clinics treated 1,330 inpatients and 4,736 outpatients during fiscal year 2012. Here is a percentage breakdown of the inpatients as sorted by diagnosis:

Dennis’ Story

He Gave the Hospital a Second Look and It Gave Him a New Life.

Photo: David Croxford

Life was going well for Dennis Okada.

He was part of a team that had just won a national championship in spear fishing, was a master diver, a double-black-belt martial artist and loved his job as an Aloha Airlines airplane mechanic. He was a youthful 41 years old.

But his good fortune changed in 1986 while tank diving at 150 feet below sea level off Rabbit Island. He surfaced too quickly and lost consciousness.

Okada developed decompression sickness, commonly known as the bends, and ended up in a hyperbaric chamber. Doctors predicted two hours of treatment and he could leave.

But two hours turned into two weeks in the chamber. Okada ended up at the Rehabilitation Hospital of the Pacific, paralyzed from the waist down and barely able to move at all. He would never walk again.

Rehab Hospital would help Okada begin his physical recovery and adjust to life as a paraplegic. However, the biggest challenge was his emotional recovery.

“I wasn’t the most cooperative patient. I was depressed and didn’t want to be there,” says Okada. “It was as if someone turned off the switch and I couldn’t turn it back on. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to turn it back on.”

After Okada finished his four months at Rehab he had no intention of ever returning. And he didn’t, until 19 years later, when he met mouth painter Morris Nakamura at a craft fair.

Nakamura, who lost the use of his arms and legs due to muscular dystrophy, urged Okada to go back to Rehab to check out the hospital’s Creative Arts Program.

Okada had never painted before, so it took persistent prodding from Nakamura before Okada checked it out.

“My first two paintings were pretty bad, but after about three or four paintings, it was kind of fun,” recalls Okada. He soon discovered a passion for art.

“It was only then, after so many years, that I started to look at things differently when it came to the hospital,” says Okada, who has been painting for seven years now. “I believe this is a place where there can be new life, new hope and new dreams, if you are willing to take it and not be stubborn and hard head, like I was.”