Hawaii Business Environmental Report: Fuel Leaks

Two years ago, 27,000 gallons of jet fuel leaked from the military’s giant Red Hill underground storage tanks. The Navy more fully explains what went wrong then and answers the question: Will further or bigger leaks happen and contaminate a main source of Oahu’s drinking water? Not surprisingly, the Honolulu Board of Water Supply is skeptical of the Navy’s answer.

“Here are my takeaways,” says Rear Admiral John Fuller. “The tanks are not leaking, the water is safe and we’re doing everything we can to make sure that continues.”

Fuller, commander of Navy Region Hawaii, is trying to assuage lingering concerns surrounding the accidental release in January 2014 of at least 27,000 gallons of jet fuel from one of the gigantic underground tanks at the Navy’s Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility. That event, and subsequent revelations about aging equipment and shoddy maintenance, have stoked fears of a catastrophic leak at the historic facility. Two years later, we’re still trying to figure out whether our drinking water is safe.

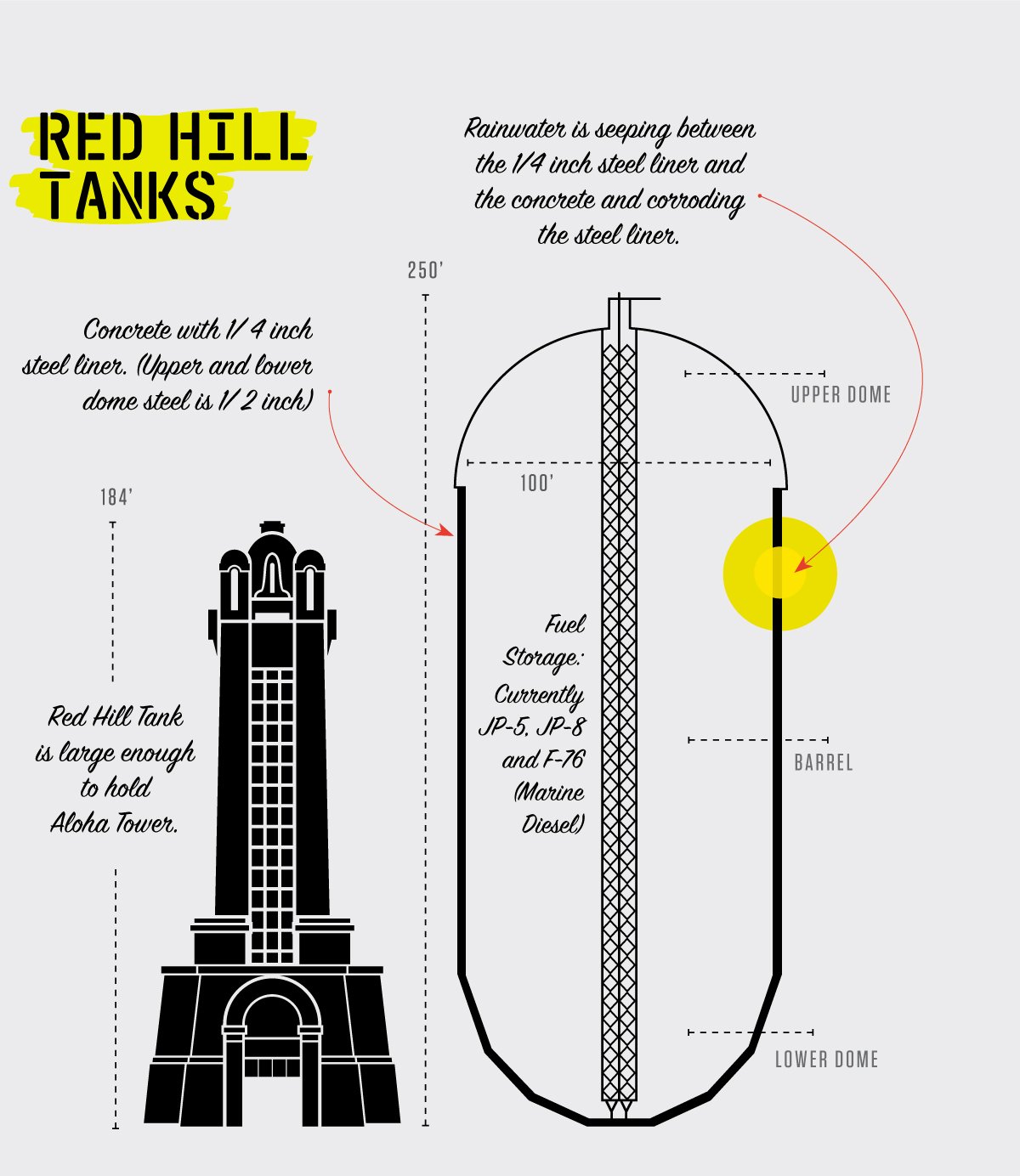

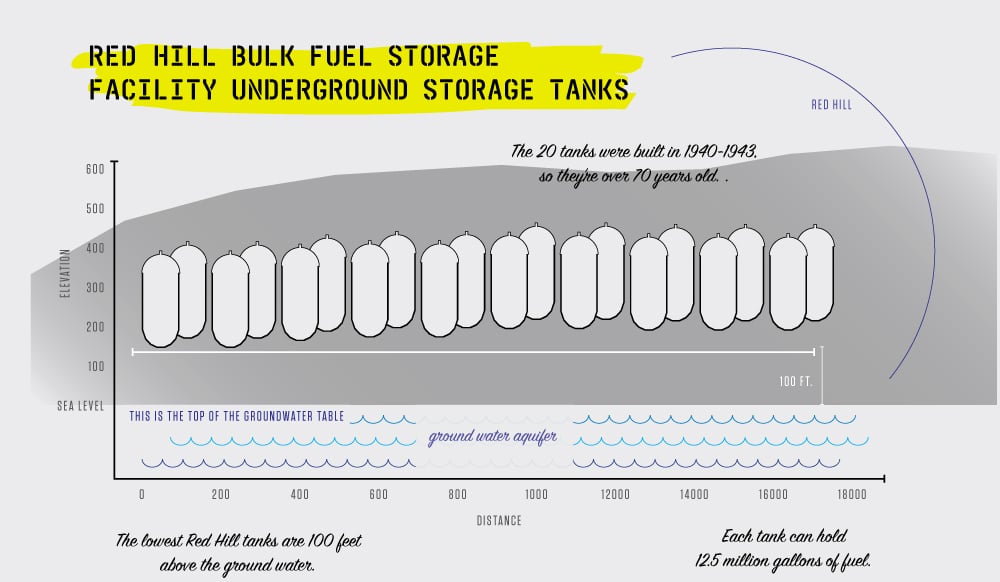

Those fears are largely based on the enormous size of the Red Hill complex, which is believed to be the largest underground fuel storage facility in the world. It consists of 20 tanks, each of which is about 23 stories tall, 100 feet in diameter and capable of holding up to 12.5 million gallons of marine or jet fuel. Modern oceangoing supertankers carry about 84 million gallons of oil, so you would need about three of them to equal Red Hill’s capacity.

Constructed during World War II, the tanks are carved directly into the basalt, 100 feet below Red Hill. The concrete walls of the tanks are three to four feet thick and lined with quarter-inch steel. The tops and bottoms are domed, so that the tanks resemble gigantic Tylenol capsules standing on end. Two tunnels connect them: An upper tunnel provides access to the top of each tank; a lower tunnel houses the pipelines and other equipment that carry fuel the three and a half miles between Red Hill and Pearl Harbor. The whole system took 3,900 people three years to build, working around the clock, including through the attack on Pearl Harbor.

One way to visualize the scale of the Red Hill facility is to imagine a phalanx of 20 towers, marching in pairs up the narrow ridge that separates Moanalua and Halawa valleys. Each of them is a bit taller than the Bank of Hawaii headquarters downtown at Bishop and King streets, and collectively they can hold enough fuel to fill the tank of every car, truck, bus and motorcycle in the state, 12 times over. In short, Red Hill is an engineering wonder of the world.

The Conflict

Red Hill is also perched directly over the Moanalua/Waimalu Aquifer, which provides up to 25 percent of Honolulu’s drinking water. In fact, the bottom of the lowest tank, Tank 1, is only 100 feet above the aquifer’s water table. When Fuller says, “the water is safe,” that’s the water he’s talking about. Despite his assurances, not everyone is convinced the aging tanks are reliable.

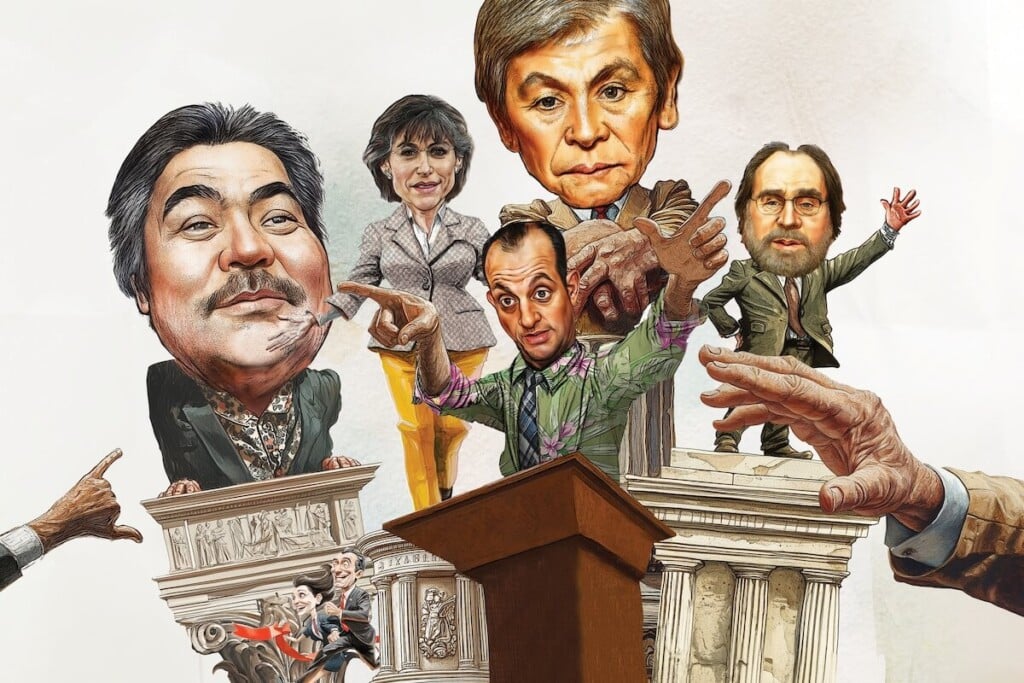

At a public hearing last June, hundreds of community members gathered to express outrage over the Navy’s handling of the 2014 leak. Members of the City Council and state Legislature have also been harshly critical.

Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard has described the Navy’s plan to deal with the leak as “woefully inadequate.” But the most important critics of Red Hill are officials at the Honolulu Board of Water Supply, who have savaged the Navy for its past management of the facility, and have been suspicious of its plans to prevent future leaks into Oahu’s water supply. Their skepticism is a useful lens through which to view the past and future of Red Hill.

As an example of the Navy’s mismanagement, water board officials cite a scathing 2009 report by the Navy’s own auditor that criticizes the Navy’s poor record-keeping and lax maintenance efforts at the facility. For example, the audit, which the water board had to use the Freedom of Information Act to obtain, notes that “6 of the 18 active tanks have no recorded (maintenance) efforts for 27 to as much as 46 years.” This negligence persisted for decades, despite evidence that the tanks leaked as early as 1948.

Erwin Kawata, the program manager for the water board’s Water Quality Division, has tabulated the leaks listed in the Navy’s own rudimentary records. “If you add up the numbers,” he says, “they come to a little over 209,000 gallons. And this list ends in the mid-1980s.”

“There’s ample evidence that Red Hill has a long history of unscheduled fuel releases. Core samples taken in 2008 revealed petroleum products in the basalt beneath 19 of the 20 tanks.”

In other words, there’s ample evidence that Red Hill has a long history of unscheduled fuel releases. Core samples taken in 2008 revealed petroleum products in the basalt beneath 19 of the 20 tanks. This provoked the creation of a groundwater protection plan, an earlier agreement between the Navy and state Department of Health. Then came the leak in January 2014.

For its part, the Navy says that, while its oversight at Red Hill was lax for many years, it has been more scrupulous since 1988, when the federal Environmental Protection Agency changed its rules concerning underground fuel storage tanks.

“Prior to 1988,” says Captain Dean Tufts, commanding officer of Navy Facilities Engineering in Hawaii, which operates Red Hill, “our records aren’t perfect, no doubt about it. But, since 1988, the only release we’ve ever had at Red Hill is the January 2014 release.”

Fuller corrects him. “We lost six gallons once.”

“That’s true,” Tufts says. “We lost five or six gallons in the tunnel one time. That was spilled on the floor and cleaned up, not into the environment.”

The Agreement

A big part of the water board’s current criticism hinges on its concerns about the agreement reached between the Navy and the two government agencies that regulate underground fuel storage tanks in Hawaii, the state Department of Health and the federal Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA. (This is a story about the military and the government, so please excuse the acronyms; believe us, we tried to keep them to a minimum.) This document, called an administrative order of consent (AOC), is a legally enforceable agreement and prescribes a long list of actions the Navy must take to bring Red Hill into compliance with environmental regulations. The statement of work (SOW) associated with the AOC addresses seven broad subjects:

• Improving tank inspection, repair and maintenance;

• Reviewing potential upgrades to the tanks;

• Improving the facility’s ability to detect leaks and test tank tightness;

• Addressing current and future corrosion and metal-fatigue practices;

• Investigating and remediating past releases;

• Developing better approaches to protect and evaluate groundwater; and

• Thoroughly assessing the risks and vulnerabilities of the Red Hill facility.

Collectively, these bullet points offer a useful outline for how to address the issues at Red Hill. Individually, though, each highlights the difference in perspective among the players in the Red Hill saga. For example, the Navy believes its current regime of tank inspection, repair and maintenance is already robust.

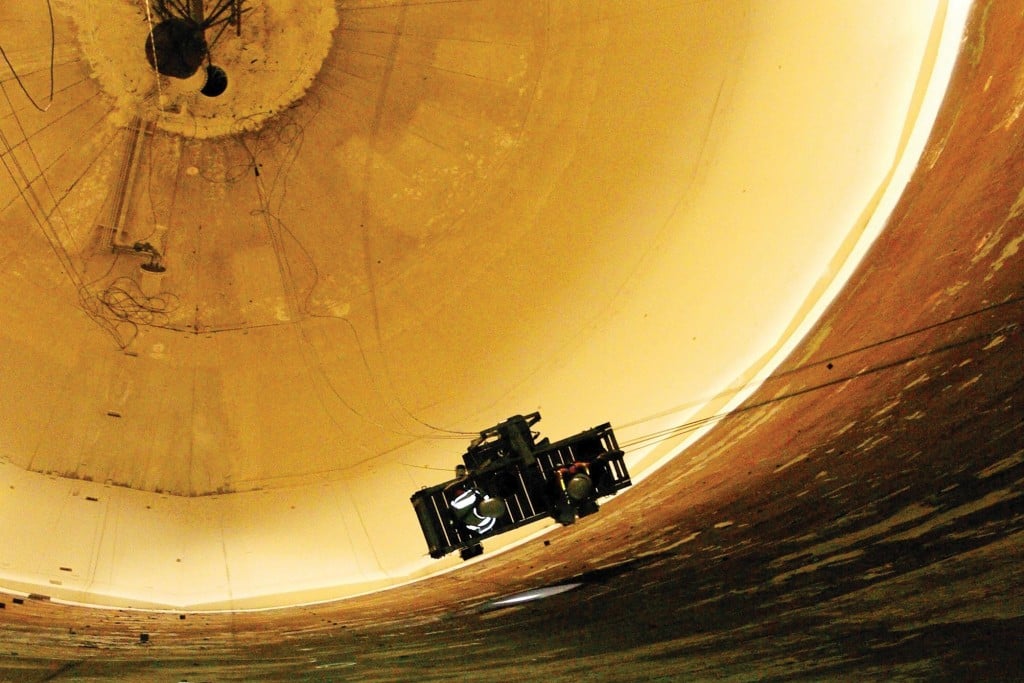

“Right now,” Tufts says, “we take a tank down for about three years and we go inside and clean the entire tank. We also inspect all the walls on this huge tank. We X-ray all the walls and look for any anomalies in the steel’s thickness. The steel is a quarter-inch thick, backed by 2.5 feet to 4 feet of concrete, backed by the basalt rock. If there are any kinds of nicks in the steel, what we’re finding is that it’s not corrosion. There’s no air down there. There’s nothing conducive to corrosion at all underground. What happened is, when they installed it, a hammer or something hit the back of the steel and gouged it or something like that. But there are thicknesses from a quarter-inch to something smaller than that. When we find those thin spots, we weld another quarter-inch plate of steel over those. Basically, every time we upgrade a tank, we’re just putting new steel on the inside of the tank, and the tank becomes a tiny bit smaller.”

The water board takes a harsher view. Pointing to the 2009 Navy audit, Erwin Kawata, program administrator for the Water Quality Division at the water board, notes, “The auditor’s report also talks about a lot of corrosion.” For example, he says, photos of the interior of Tank 16 show “a section of the steel liner, between seven feet wide and 11.5 feet tall, that was so damaged it needed to actually be replaced because of rust.” It’s those basic repairs that the water board fears the Navy will not do soon enough.

Mostly, though, the water board insists the AOC and SOW aren’t sufficient. For example, the water board officials criticize what they view as the absence of hard deadlines in the agreement. Instead, the AOC states that if the improvements specified in the SOW aren’t made to the satisfaction of the state Department of Health and EPA, the Navy must close the Red Hill facility within 22 years of the AOC’s signing.

In a list of comments it supplied to the regulators, the water board notes: “The timelines for SOW task planning and completion, approval of deliverables, funding of work and dispute resolution are too long and are poorly constrained. The dispute-resolution process has no apparent limit on duration, potentially continuing for many months or more, thereby delaying implementation of the needed protections for our drinking water supply.”

Their comments go on to suggest that the Navy be allowed no more than six months from the signing of the AOC to achieve five key goals:

“(1) upgrading the facility tanks to meet U.S. EPA updated underground storage tank regulations,

(2) tank testing and rehabilitation/closure,

(3) characterization of the full nature and extent of the 2014 fuel release within the sub-surface,

(4) participation by major stakeholders in planning and decision-making, and

(5) regular public meetings to educate residents by sharing findings and decisions.”

The Navy, of course, has a different perspective.

“I’m a little surprised the Board of Water Supply says there aren’t deadlines,” says Tufts. “There are deadlines. They aren’t specific dates, but they say, for example, ‘Once you finish this, you have 60 days to finish that; once you finish that, you have 90 days to finish this.’ ”

Part of this dispute is because the Navy and the regulators still need to complete scoping the work – that is, they have yet to agree upon the specific goals and deliverables. “We’ve already gotten through scoping meetings for a couple of the sections of the SOW,” says Tufts, “and now we’re on a timeline. We have 60 days to produce a scope of work. Then, we’ll have a certain amount of time to produce an RFP and go out for proposals.”

Tufts also points out that these requests for proposals represent major opportunities for Hawaii contractors. “We just recently awarded a $43 million military construction contract to better the ventilation, the fire suppression, and we’re putting additional oil-tight doors in the tunnel.”

Those oil-tight doors, it should be noted, are part of the Navy’s “red-celling” process. Red-celling basically means identifying worst-case scenarios, which, in this case, would be a catastrophic leak flowing down the tunnel and into Pearl Harbor.

The Leaks

Another water board criticism of Red Hill is the facility’s leak detection system is grossly inadequate.

“That’s just not true,” says Tufts. He gestures to Lt. Cmdr. Andrew Lovgren, who runs day-to-day operations at Red Hill. “Drew, here, can measure the level in the tanks, to within a sixteenth of an inch, with his automatic fuel handling equipment. This is in every single tank and it measures off of mass and temperature, and automatically does the calculations by computer. We have the alarms set so that, if we have any unscheduled fuel movements of about half an inch, which is about 2,400 gallons in a 12.5-million-gallon tank, an alarm goes off. In addition to that, every four hours, Drew’s guys do a manual measurement for every tank that’s filled with fuel.”

But the water board doesn’t think those measure-ments are sensitive enough to detect leaks. In its comments on the SOW, the water board demands the Navy use techniques that meet the current Code of Federal Regulations, which means being able to detect a leak of one gallon per hour or less.

“There are very substantial, detectable levels of petroleum contaminant in the groundwater, and…it’s coming from the tanks.”

Erwin Kawata

Program Administrator, Water Quality Division, Honolulu Board of Water Supply

The water board and the Navy also differ in how they characterize the contamination in the groundwater. Kawata says the Navy’s own data, since 2005, suggest at least a couple of additional incidents. Hydrocarbons are a chief component of petroleum, so measuring hydrocarbon levels is a good way to detect leaks. In a chart that Kawata prepared of hydrocarbon levels in the groundwater, the 2014 leak is clearly evident as a spike. The problem, he says, is there was a similar spike the following April, after Tank 5 was emptied, as well as a very large occurrence in 2008. “What this graph shows,” he says, “is there are very substantial, detectable levels of petroleum contaminant in the groundwater, and that it’s coming from the tanks.”

The Honolulu Board of Water Supply has led criticism of the Navy’s handling of the Red Hill leak, and, in particular, Ernest Lau, left, manager and chief engineer at the water board, and Erwin Kawata, program administrator for the board’s Water Quality Division. (Photo: Aaron Yoshino)

Moreover, he says, that contamination is moving away from the tanks. Although earlier Navy data suggested groundwater primarily flowed from mauka to makai, later evidence indicates there’s also a substantial flow to the northwest. Hydrocarbons have been detected at new monitoring wells near the Halawa Correctional Facility, more than 1,000 feet northwest of Red Hill. That, as Kawata points out, is in the direction of the Halawa Shaft, one of Honolulu’s primary sources of drinking water.

From the Navy’s perspective, all of this is true, but there’s less to the data than meets the eye. Fuller, for example, thinks the terminology is emotionally charged.

“I would like to be careful with the term ‘spike,’ ” he says. “There have been detects of trace amounts of fuel constituents near the Navy drinking water shaft. When I say ‘trace amounts,’ we’re talking 17 parts per billion, as opposed to zero. That’s what some people are calling a spike. There’s a detect, but it’s off of zero. The misperception is that there’s a spike, but the numbers were small enough that the testing facility had to estimate the amount because the numbers were so low. The 17 parts per billion is also below the threshold of something we should be concerned about, which is 100 parts per billion.”

Keith Kawaoka, deputy director at the state Department of Health, agrees. He says the Navy’s fuel monitoring system indicates there haven’t been recent leaks.

“From probably 1983 through 2014,” he says, “there are only small fluctuations, and no significant loss of fuel. This indicates that most of the fuel that’s trapped in the rock and hasn’t made it to the groundwater is probably from old releases. So, the incident in January 2014 presents us with a unique situation where we have a fresh, documented release, and we’re still seeing the impacts of that release in the groundwater. We have pulsations as we have rainfall events that basically come in contact with any trapped fuel and cause a dilution effect, where the water is pushing some of that fuel down into the groundwater.”

This assessment is mirrored at EPA. “There’s a lot of concern and fear that’s not supported by the data,” says Steve Linder, who manages EPA’s underground tank storage program for Region 9, which includes Hawaii. “People think there’s a massive amount of fuel in the groundwater. In fact, the monitoring wells only show trace amounts. We’re not seeing massive amounts of contamination. There’s a lot of talk about what kinds of failures could have occurred, how much fuel would be released and how much impact would it have. But a lot of that has been speculative in nature.”

He adds that this observation justifies the slower, more circumspect pace built into the AOC. “At this point,” he says, “we don’t see an emergency-level problem. We know we need to move quickly, and if we find the risk is much greater than it seems now, we’ll revisit” the details of the AOC.

EPA’s views also dovetail with the Navy’s when it comes to some of the proposed remedies to Red Hill’s problems. For example, the water board has proposed double-lining all of the tanks, but EPA associate director Tom Huetteman says it’s not so simple. “You have to ask yourself, ‘How am I going to maintain the structure?’ You can create some ‘improvement’ that appears to be a better way to go, but if it really prevents access to the rest of the tanks for inspection and repair, is it actually better?”

The tank-within-a-tank concept is also daunting from an engineering point of view. Some quick arithmetic: A gallon of marine diesel weighs more than eight pounds. That means the full capacity of one of the Red Hill tanks – 12.5 million gallons – would weigh more than 51,000 tons, greater than the total displacement of the battleship Missouri. Building a structure to support that weight would require unprecedented engineering innovations, and that’s not even counting the weight of the inner tank itself.

Similarly, calls for exploratory drilling to find and remediate the 27,000-gallon 2014 leak may present technical challenges. As the Navy’s Tufts explains, “We’ve heard from the Board of Water Supply and others, ‘Hey, you’ve got to drill wells and go find that fuel.’ Well, if you start drilling wells, that’s just a free pathway to the aquifer. So, step back and think about it logically.”

It’s this slow, deliberate pace that frustrates critics, like the water board.

“This is one of the issues we have,” says Fuller. “When you say 20 years and people believe that the tanks are currently leaking, they think there will be 20 years of continuing contamination. But the tanks are not leaking. So, the improvements we’re going to make are happening in the right time frame. It takes a long time to refurbish the tanks as we are right now. The AOC is going to drive us to look for emerging technologies that will help us go faster over time, but we’ve also got to make sure we’re not such an early adopter of technology that it’s going to have larger consequences later. We have to do this right. There has to be a fact-based approach to what we’re doing. Because both missions are so important, we really can’t afford to do the work two or three times. This is really a ‘measure twice, cut once’ scenario.”

January 2014

Ultimately, the tension between the water board and the key signatories of the AOC – the Navy, Department of Health and EPA – comes down to the perception of urgency. The water board views the situation at Red Hill as a crisis, an imminent and potentially irreversible threat to Oahu’s drinking water supply.

The Navy and its regulatory agencies, on the other hand, believe the problems at Red Hill are more chronic in nature, and that they’re best dealt with in a cool, methodical manner. Which of these two perspectives you think is right depends largely on whether you believe the Navy’s assertion that there are no leaks at Red Hill today. Water board officials point to the Navy’s abysmal 40-year record of maintenance and repair, at least prior to 1988, and conclude the January 2014 event was just one leak in a long chain of leaks. The Navy, whose personnel change every few years, looks at the last few years of regular maintenance and investment at Red Hill and concludes the situation is under control. If that’s the case, then, as Tufts puts it, “What the hell happened in January 2014?”

“There were three issues,” says Fuller. “Poor contractor work, poor oversight and we didn’t follow our own procedures. The release was completely avoidable, but we’ve taken all the necessary internal looks and external looks to make sure that it will never happen again.”

Rear Admiral John Fuller

Commander, Navy Region Hawaii

Tufts goes into more detail.

“In January 2014,” he says, “we had done five tanks the same way we modernize all the tanks. We were doing a sixth, Tank 5, but this one was done by a different contractor than any of the first five, and we had never had problems with those first five. But this contractor goes in, spends three years, does all the welding, does all the cleaning, does all the inspections, and an American Petroleum Institute 653 certified engineer from the contractor signs off on it. It’s like driving a new car out of the showroom. Then, we start getting alarms as we fill the tank. It’s like when your check-engine light goes on. You think, ‘That can’t be right; it’s brand new; it was just modernized.’ And this was our mistake – this was the procedure the Admiral was talking about – we just reset the alarm. That happened a couple of times. So, by the time we realized, ‘Oh, my gosh, this is really happening,’ we had to move all the fuel into another empty tank. And by the time we moved the 12 million plus gallons into another tank, we had already lost 27,000 gallons.”

That’s the crux of the matter. Even if the Navy is right and Red Hill is safe and well maintained, that doesn’t change the fact that we may have as much as 250 million gallons of jet fuel and marine diesel sitting over one of the most important sources of drinking water in the state. That’s inherently dangerous.

Fuller emphasizes the Navy drinks that water, too, and has a stake in protecting the health and safety of its personnel. “We’re not going to walk away from our commitment to make sure the drinking water my family, your family and everybody that lives here consumes is safe.”

But Fuller tempers this wholesome optimism with the characteristic realism of a military man. Reflecting on the tension between the fuel storage function of the enormous Red Hill facility and the delicate environment it sits in, he notes, “In a lot of cases, I would say people are looking for almost a 100 percent guarantee of zero risk. There’s no way to give a 100 percent guarantee of no risk.”