Pop-up Restaurants and Stores: Great Places to Start a Business

Until a few months ago, I thought a “pop-up” was an old-fashioned three-dimensional card or book that surprised you with a magical foldout that popped up as you opened it. Now, I know modern pop-ups are fleeting events – whether of food or fashion – that appear, disappear and then reappear, often in surprisingly different spots. No two are alike.

You can’t find out about pop-ups unless you live where they live – on social media. So I joined the hordes tweeting, yelping and liking, and on my Facebook page, my friends now include an eclectic bunch: Miso & Ale, The Pig and the Lady, Roam, EightyTwo Creations and StreetGrindz.

Some pop-ups are stores or restaurants that appear for a day or a week. Some pop-ups occur in restaurants, but aren’t about food – a musician featured for a special occasion, art from a particular artist. There are pop-ups in private homes that feature crafts and jewelry, or music and poetry. They are usually more than just a table at a farmers market or craft fair, though those locations sometimes supplement a pop-up’s irregular appearances.

Henry “Hank” Adaniya, the owner of Hank’s Haute Dogs, sees pop-ups as short-term food events that emulate a restaurant experience, often in a borrowed venue.

“They offer chefs and cooks a low-risk way to present themselves to the public,” says Adaniya. He has hosted pop-ups for The Pig and the Lady and created one of his own, hank’s downtown.

“They are also known as ‘underground’ restaurants that exist below the radar. In many ways, catering has the same dynamics as pop-ups. Someone has a burning desire, another has a space they’re willing to lend or rent out and, if their paths cross, voila!”

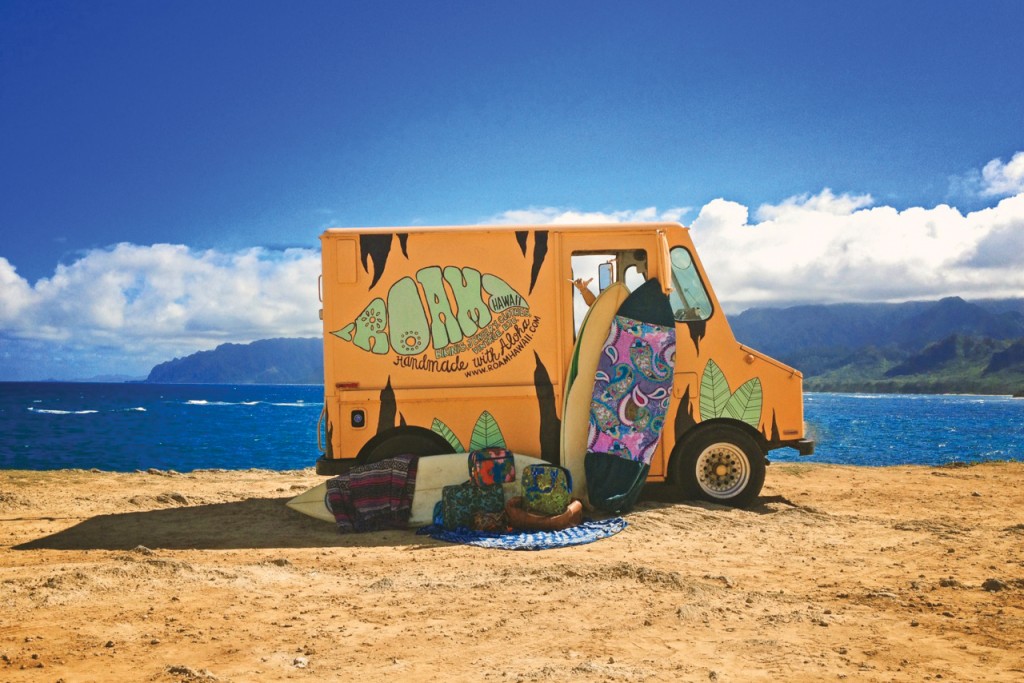

Brooke Dombroski is a photographer, graphic designer and owner of Roam Hawaii, a designer-collective mobile marketplace of one-of-a-kind objects. She works with three business partners who are also her best friends.

She started Roam Hawaii out of an old manapua truck, but has also participated in pop-ups at bricks-and-mortar stores, which are great partners because they can provide quick exposure for pop-up shops like hers. “Creatively for us, it’s very refreshing and exciting to team up with established companies,” she says.

Sometimes, a pop-up is born as a solution to a problem. Tanna and Bryson Dang held their first Black Friday sale at their Ward Warehouse boutique, Eden in Love, in 2009. Customers packed the store and others lined up around the mall for hours and their merchant neighbors were upset at women blocking access to their stores.

Ever since, the Dangs have hosted a Black Friday pop-up in a second-floor conference room at Ward Warehouse. More space, more people, more merchandise and a lot more work. “It takes us three full days to set the rooms up,” says Tanna Dang.

Dang says marketing the pop-up event involves more than social media. Staff staple minifliers to all customer receipts during November, put up a banner at Ward Warehouse and do much more to get the word out.

Jason Koji, based in Hilo, supplies venues and organizes pop-up shops under the brand EightyTwo Creations, which is the name of his print shop. The 30-year-old has been self-employed since his early 20s and actually started his first business while a student by selling stickers at Hilo High School.

“To me, pop-up means a special retail event,” says Koji. “It usually consists of independent clothing or jewelry companies. And, for me, it’s supporting local up-and-coming businesses.”

His first pop-up involved several specialty companies including Shipwrecked (which makes jewelry) and Cultural Blends, but soon there were others: BoomBoom Bikini, 808 Empire and Shawn Pila Photography.

“Pop-ups are great ways to cross promote,” says Koji. “Both my shop and whomever I work with benefit by combining our networks and contacts. Vendors also benefit because they’re not locked into a lease and avoid startup costs that go into opening a retail business.”

Koji says he handles most of the promotion through a network of 10,000 contacts on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and his mailing list.

“Whoever is renting space will do the same as far as online promo,” he says, “and we’ll cross promote with the brands we work with.”

Koji says he gets paid either with a set price, which includes the rental space, electricity, insurance and advertising, or with a percentage of sales, but he’s not specific on the dollar amounts.

Shawn “Doc” Boyd, founder of the Greenhouse (now called HQ HNL), an innovation and pop-up hub in Kakaako, says the modern pop-up builds on a long tradition.

“How many years have movie theaters been running previews for weeks or months ahead of the film, so that, by the time the movie comes to town, everyone wants to see it?” he asks.

“That’s exactly the concept of a pop-up,” says Boyd, whose Greenhouse helps entrepreneurs, builds websites, hosts events, teaches classes and gets the word out.

“You want to test the idea, get people to respond to the preview and then set up your brick and mortar. A lot of people think that you have to have the site first, but that’s a huge investment. This creates the desire first and measures it.”

Photo: Lee Ann Bowman

Poni Askew at one of the Eat the Street events that she helped create.

There’s no way to talk about pop-ups in Hawaii without speaking of food trucks, and you can’t talk about food trucks unless you start with Poni Askew. Poni, her husband, Brandon, and their company, StreetGrindz, have been leaders in the food-truck and pop-up movement. Their “Eat the Street” events – the last Friday of the month in Kakaako and less frequently in other Oahu neighborhoods – draw more than 40 food trucks.

The Askews loved the idea of offering food-truck chefs the option of doing something original, even if only for one night. On one occasion, Youssef Dakroub, the owner of the Xtreme Tacos lunchwagon, turned his mobile venue into an evening of food from his Lebanese homeland and it was a hit. “Arabian Nights” was born and has become a recurring pop-up.

Now, Poni Askew and her partners have founded a permanent location for pop-ups and other food experiments. Taste at 667 Auahi St., near the Greenhouse in Kakaako, features a supervising chef, Taste partner Mark “Gooch” Noguchi, and a rotating selection of pop-up restaurants, some created by food-truck operators, The Pig and The Lady and others.

Photo: Lee Ann Bowman

Eat the Street Kakaako has a different theme each month. The Oct. 26 theme was Dia de los Muertos, the Mexican holiday known as the Day of the Dead.

“It’s been thrilling to see the excitement in food entrepreneurs’ eyes,” Askew says. “Many have dreamed of owning their own bricks-and-mortar and Taste gives them the unusual opportunity to take a step closer. Having this space for even one day a week strengthens their dream of owning their own café or restaurant some day, but also educates them to some of the realities involved. Likewise, our guests receive an ever-changing menu out of the same four walls and they can look forward to coming back to dine with us at Taste. It’s a win-win for everyone.”

McGee’s Pop-up Tested His Food Concept

BY LEE ANN BOWMAN

Bob McGee now owns a brick-and-mortar restaurant, The Whole Ox in Kakaako, but his first Honolulu restaurant was a 10-week pop-up. Photo: David Croxford

Put Bob McGee in an imaginary police lineup and ask, “Which one owns The Whole Ox?” You’d pick him in an instant. He’s big and barrel-chested and looks to be just the guy who’d create an informal, open-fronted restaurant with long, thick-boarded picnic tables in Kakaako and smack a moniker on it like “The Whole Ox.”

Indeed, McGee’s background is beefy, too. He was only 14 when a local burger joint in Avon, N.Y., hired him to grind beef and tie roasts for the in-house butcher. But he is also a graduate of the Western Culinary Institute in Portland, a Le Cordon Bleu school. And at Portland’s famed Higgins Restaurant, he learned the art of making sausages and other cured, smoked and preserved meats. He was part of the team when Higgins received a James Beard Award for best restaurant in the Northwest.

While he now has his own bricks-and-mortar restaurant, The Whole Ox was preceded by Plancha, a 10-week pop-up that served a mere 20 people a night, and operated three nights a week from September to November 2011 out ofMorning Glass Coffee and Cafe in Manoa. Plancha, which featured a different menu each week, helped him test his theories, price points, menu items and business acumen.

“I think that we received a little notoriety, mainly because we were a little ahead of the curve,” says McGee. “There were very few pop-ups operating at the time.”

McGee says a pop-up restaurant generally uses a space that the chef does not own or lease long-term, but aims toward the chef’s own clientele. McGee’s pop-up happened because he had a food concept he wanted to try and a friend, the owner of Morning Glass, had available space in the evenings. “It was pretty much that easy,” McGee says.

Every pop-up has its own rules, based on that unique partnership.

“Maybe a percentage of rent is paid, based on overhead and profit,” he says. “Certain amounts of refrigerated space or dry storage may be allocated. They are usually a pretty organic derivation, so the idea mutates often.

“The one word that describes pop-ups best is ‘variety!’ ”

Follow the Gypsy Chefs from Venue to Venue

BY LEE ANN BOWMAN

They call themselves “gypsy chefs,” because the four young men who started with a pop-up at Moke’s Bread & Breakfast in Kailua more than a year and a half ago have since shown their stuff at a half dozen or more brick-and-mortar restaurants, as well as setting up tents at various festivals and catering private events. Among their chef’s tools are smartphones, an iPad and social media.

“How many times have we done this?” one of them asks another. There seems to be no definitive answer.

The gypsies, better known as Miso & Ale, are chefs Chris Okuhara and Chris Gee, business partner Keola Warren, and graphic designer and social media guru Gavin Murai.

I caught up with them at Coffee Talk in Kaimuki. For four hours on a late October evening, customers dropped in (no reservations were accepted) to enjoy “appeteasers” of Roasted Beet Salad and The Great Pumpkin Soup, entrees such as The Open Faced BLAT, Chinese Style Beef Stew and The 2 a.m. Special, and parfait and pastry desserts.

Miso and Ale partners, from left, Chris Okuhara, Keola Warren, Chris Gee and Gavin Murai surround Liz Schwartz, owner of Kaimuki’s Coffee Talk, who invited the pop-up team to present an evening of meats and sweets on Oct. 26.

Photo: Lee Ann Bowman

The location was thanks to Coffee Talk owner Liz Schwartz, who was on site and seemingly enjoying every moment of the pop-up, and for good reason. For years, she’d kept her coffee, sandwich and pastry shop open 5 a.m. to 10 p.m. “But at night it had become a library,” she notes. People brought books and laptops and, often, their own food and drinks. Maybe they’d buy a cup of something. Maybe.

“I wasn’t making money. I had to have staff on and pay for air and lights and so forth, so I started to think about closing early.” As of Oct. 1, she started closing at 6 p.m., which meant nights were available for such experiments. Besides, as a self-proclaimed foodie, she was fascinated by pop-ups and “in awe” of this particular one.

The Miso & Ale gypsies (the name reflects their love of Asian fusion and their favorite beverage) have come to love the creative freedom of using different venues. They have become so popular that established restaurants are now coming to them instead of vice versa. And they recognize that when they leave after a pop-up, they’ve created a whole new customer base – not just for themselves, but for the brick-and-mortar restaurant.

They also like the flexibility of seeing what works rather than the drudgery of doing the same thing every day, and the losses are not as great as with a standard restaurant.

Like other pop-ups, they rent or pay a flat fee to commercial kitchens for food prep, but they also have family kitchen connections: Okuhara’s grandparents own Like Like Drive Inn and Moke’s in Kailua is owned by Warren’s family.

Each time they pop up in a different place, the agreement with the owner is unique to that site. In the case of Coffee Talk, Schwartz asked for a percentage of the evening’s take. Sometimes they’ll pay a flat rate.

“Our cover average (the amount that a restaurant sets as a goal to take in per customer) is variable by event. We’re learning that events in Mililani are different from events in Kakaako,” says Okuhara.

The big question: can you earn a living doing this? Yes, he adds, though it’s the catering part of their business – weddings, birthdays, anything – that puts them into the black. On those occasions, they’re not limited to Asian fusion. “We’ll cook anything anywhere,” he says.

And the whole team stays from setup through cleanup.

What are the downsides of being “a gypsy chef”? A few they mention: “You don’t have your own space, ever … There’s no place to keep all your stuff … You really beat up your car, picking up everything.”

They all agree on another downside: Pop-ups are not an option for people who just want to show up at work every day and have their own space.

From Ethiopia to Pop-up

BY LEE ANN BOWMAN

Jim and Meron Spencer loved having friends over for dinner, and guests loved the great conversation and the multicourse dinners of Ethiopian food prepared by Meron (pronounced Meh-roan). The parties ended with Ethiopian coffee roasted and ground by Meron in what she described as “sort of like a tea ceremony.”

She began cooking for her own family when she was just 8, while growing up in Ethiopia’s Kaffa region, where coffee originated and from which the beverage got its name. The couple met in the capital of Addis Ababa eight years ago while Spencer, a professor of urban planning and political science at UH-Manoa, was working on a health project. In 2006, they married there and, a year later, Meron and her then-7-year-old son arrived in Hawaii.

Meron Spencer prepares the dishes of her native Ethiopia.

Photo: Courtesy Jim Spencer

Ethiopian food was not new to Jim Spencer, who is the son of a Vietnamese mother and American father. “I always knew Ethiopian food growing up in New York,” he says. “And before coming to the U.S., we spent a lot of time in Southeast Asia, where there are lots of Ethiopian restaurants in major cities.”

But there were none in Honolulu. Encouraged by friends who relished their gala dinner parties, the Spencers set out to change that.

They got the chance two years ago when a phone call introduced them to JJ Praseuth Luangkhot, chef and owner of JJ Bistro & French Pastry in Kaimuki. He had just invested in a new restaurant, J2 Fusion, and had heard about their great dinners. He offered them the use of his new facility one night a week and the Addis Ababa Hawaii pop-up restaurant was born.

The Spencers started with a Thursday night. “We said, ‘We’ll take care of the food and you take care of the service, the gas, the electricity and refrigeration and then we’ll split the revenues,’ ” says Spencer.

“I just sent out an email to friends and colleagues and asked them to send it out, got it on Facebook and asked for reservations,” he says. That first night had a deluge of 115 people, more than they could handle, but that provided an important lesson: A pop-up restaurant is more than just great food.

“Managing the people, that was really hard,” he says. “We could only seat 85 and some left. That was our mistake that first night, accepting too many reservations.

“But one of the things Meron also realized is that it’s not just about eating, it’s about culture, about education, about socializing. … That first night the governor came and the second night somebody who writes a blog wrote it up. There were reviews on Yelp, lots of different types of reviews. We never did any other type of advertising.”

The couple ran that pop-up for eight months, then moved to other venues such as the Lemongrass Cafe in Chinatown.

“Basically they cover the space and we cover all the food,” says Spencer of the restaurants they work with. “We’ve become kind of like the subcontractor.”

Yes, they are considering a permanent site, but they insist it will have to be “just the right situation.”