Payday Lenders

The payday lending industry in Hawaii offers short-term loans with annual interest rates of up to 459 percent. The companies say they are providing an important service, but critics argue they are soaking the needy and driving them further into debt that is costly to repay. Legislation to cap interest rates died at the state Legislature this spring, but will probably be reintroduced next year.

Before each payday Ronnette Souza-Kaawa sits down at her kitchen table armed with scratch paper, a sharpened pencil and a pink eraser. She stopped using a pen after her husband pointed out the number of crumpled, crossed-out sheets of paper around her. The 46-year-old handles the finances for their family of five and every two weeks meticulously plans out a budget.

Souza-Kaawa wasn’t always this way. “I had bad money habits,” she says, seated on a high metal stool inside the offices fronting Hale Makana o Nanakuli, a Hawaiian homestead affordable-housing complex she visits for financial counseling. The Waianae native says it was challenging to track just where the family’s money went each month, and even harder to save some of it. She maxed out credit cards and left bills overdue. When her teenage daughter had a baby last year, Souza-Kaawa had to tighten the family’s purse strings further. “She had no job,” she says, “so I had to get a payday loan.”

It wasn’t the first time she went to the Easy Cash Solutions on Farrington Highway in Waianae. She says it probably won’t be her last.

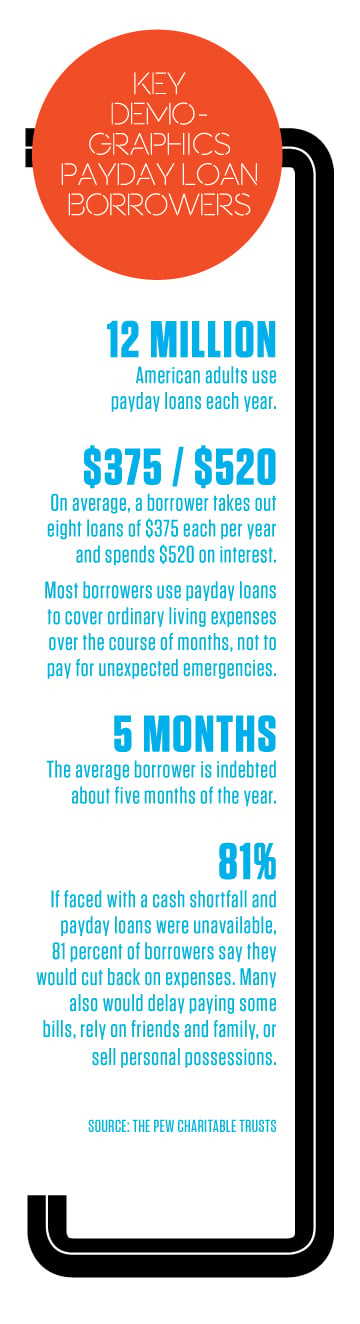

Souza-Kaawa is one of 12 million people across the country who use payday lending businesses, according to “Payday Lending in America,” a 2012 study by The Pew Charitable Trusts. Cash advances, or deferred deposits, commonly called payday loans are small, short-term and unsecured loans borrowers repay in two weeks, or on payday. They’ve long been a contentious form of credit, but the pressure to change appears greater than ever. While payday business owners and proponents argue they’re crucial to the financially underserved, consumer advocates say the payday lending business model is predatory and sets borrowers up to fail. Although borrowers get immediate relief with a quick turnaround loan, many often struggle for months to repay them. The Pew Charitable Trusts study found that an average borrower takes out about eight loans each year and is in debt roughly half the year.

In the Islands, payday lending businesses comprise a booming, 16-year-old industry, legalized in 1999. Get out of one of Hawaii’s urban centers – downtown Honolulu or resort Lahaina – and you’ll spot them fronting residential neighborhoods or in strip malls. Payday lending businesses are hard to miss with their large signs and technicolor storefront banners advertising “same day loans,” or “today can be payday!” not to mention websites that promote easy, online applications for loan approval. Hawaii’s payday lending law is considered permissive by most reform advocates: Payday lenders don’t register with the state Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs, and payday loans – their primary product – carry an annual percentage rate (APR) as high as 459 percent ($15 per $100 borrowed per two-week periods).

“IF DON’T NEED IT, DON’T TAKE OUT A LOAN. DON’T GO BORROWING $500, JUST BECAUSE YOU CAN,” SAYS RONNETTE SOUZA-KAAWA, WHO HAS PAID OFF MOST OF HER $7,000 IN DEBT THANKS TO FINANCIAL COUNSELING

While lending reform is happening in many states across the country, most notably to cap the APR interest below 50 percent, no such bill has ever passed in the Hawaii legislature. One Senate bill, proposing to cap interest at 36 percent, survived to the end of session, only to falter to powerful industry lobbying. Advocates say they hope to pass regulations next year. Until then, according to reform advocacy nonprofits such as Hawaiian Community Assets and Faith Action for Community Equity, or FACE, a growing number of kamaaina continue to use payday lenders as their only financial solution, many enveloping themselves in debt.

WHY HAWAII HAS PAYDAY LENDERS

When Ronnette Souza-Kaawa took out a $400 payday loan, she paid $60 in upfront fees. If she couldn’t pay off the loan in two weeks, she’d wind up owing $480 in fees plus the original $400.

Today’s payday loans exist because of nationwide efforts, mostly in the ’90s, to exempt these small, short-term cash loans from state usury laws. In Hawaii, the usury interest cap is 24 percent a year; in most states it’s less than 25 percent. “When these loans first came to Hawaii and other places, they were presented to the Legislature as something that was available to people in an emergency, sort of a one-shot deal,” says Stephen Levins, director of the state Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs office of consumer protection. “Unfortunately, most people who take these loans out, don’t take them out as a one-shot deal, they take them out repeatedly. It belies what the industry (first) said.”

Payday lenders make borrowing money easy. All that’s needed for approval is a pay stub, bank statement and authorization to later withdraw from the borrower’s account to get cash loans up to $600 in Hawaii to be repaid in 32 or fewer days. Unlike borrowing from a bank or credit union, users don’t need good credit or any credit to get a payday loan. And, they’re faster: Applications are processed in an average of 30 minutes.

Currently, 38 states allow payday lending businesses (four states and the District of Columbia prohibit them). But, regulations to limit payday lenders have been making their way out of state legislatures as lawmakers learn the risks associated with these types of credit. Since 2005, more than a dozen states have imposed rate caps of 36 percent or have no law authorizing payday lenders. And, in 2011, Congress established the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau; this year it released proposals to establish federal regulations on payday lenders.

The only existing nationwide restriction is the Military Lending Act, passed in 2006, which capped interest at 36 percent on payday and auto-title loans to active duty service members. Until the law changed, payday lenders disproportionately targeted military members by setting up shop just outside military bases, such as in Wahiawa, adjacent to Schofield Barracks. That’s when the faith-based nonprofit, FACE, became involved in this issue, encouraging Hawaii’s congressional members to pass the Military Lending Act. “We had a lot of military families getting payday loans and getting caught in the debt cycle,” says Kim Harman, the former policy director. Harman says the payday lending landscape shifted after passage of the law to protect service members.

The only existing nationwide restriction is the Military Lending Act, passed in 2006, which capped interest at 36 percent on payday and auto-title loans to active duty service members. Until the law changed, payday lenders disproportionately targeted military members by setting up shop just outside military bases, such as in Wahiawa, adjacent to Schofield Barracks. That’s when the faith-based nonprofit, FACE, became involved in this issue, encouraging Hawaii’s congressional members to pass the Military Lending Act. “We had a lot of military families getting payday loans and getting caught in the debt cycle,” says Kim Harman, the former policy director. Harman says the payday lending landscape shifted after passage of the law to protect service members.

In 2013, FACE started receiving calls from local families across Oahu and Maui who were in deep debt because of payday loans. The organization is now focusing on assisting the state’s lower-income kamaaina community, in hopes of passing state regulations. Staff members conducted interviews with 56 Maui families to get their stories; the following year, the nonprofit made payday-lending reform one of its top priorities. “The payday lending companies know that there is a lot of money to be made from payday loans,” she says. “The new market they’ve expanded into is in the lower-income communities, especially newer immigrant communities.”

“THE PAYDAY LENDING COMPANIES KNOW THAT THERE IS A LOT OF MONEY TO BE MADE FROM PAYDAY LOANS. THE NEW MARKET THEY’VE EXPANDED INTO IS IN THE LOWER-INCOME COMMUNITIES, ESPECIALLY NEWER IMMIGRANT COMMUNITIES.”

-KIM HARMAN, FACE POLICY DIRECTOR

While there are some national chains that operate in Hawaii, most are locally owned and operated. Craig Schafer opened his first payday business, Payday Hawaii, on Kauai in 2000 after he realized there were none on the island.

“I opened my first store in Kapaa and immediately it was popular,” he says. Within one year, he had two locations on the Garden Isle. Schafer says much of his clientele are young, working families “that haven’t built up any savings yet.” Today, he has seven locations on three islands.

“It’s a convenience thing,” says Schafer. “It’s like going to 7-Eleven when you need a quart of milk. You know it’s going to cost a little extra, but it’s on the way home, you don’t have to fight the crowds, you walk in and walk out with your quart of milk and drive home. You’re paying for the convenience.”

WHY HAWAII’S PAYDAY LENDERS THRIVE

The 7-11 convenience analogy certainly holds true for Souza-Kaawa. She lives in Waianae and works there, too, in administrative services at Leihoku Elementary. When she needed money to help her family, she simply went down the road to Easy Cash Solutions. Souza-Kaawa says she has taken out roughly a dozen payday loans in the past two years, ranging from $150 to $400. She says she’d always strive to pay them off before her next paycheck, but that didn’t always happen. Hawaii law states a single loan must be repaid in 32 days or less. “If I borrowed a high (amount), I’d pay some off and re-borrow only a little,” she says. Today, Souza-Kaawa owes roughly $1,470 from two recent loans, $1,000 of which is debt accrued by her daughter’s payday loan. Souza-Kaawa isn’t alone. According to a 2014 Consumer Financial Protection Bureau study, four out of five borrowers end up defaulting on their loans, or renewing them within the first two weeks.

Instead of taking a small loan from a bank or other traditional lenders, most borrowers feel it’s more feasible to get a cash advance; as a result, they don’t inquire elsewhere. According to the Corporation for Enterprise Development’s Assets and Opportunity Scorecard, Hawaii ranks 29th in the nation when it comes to the number of underbanked households, or families that utilize alternative and often costly, non-bank financial services for basic transaction and credit needs.

“I think it depends on what the family has done before,” says Jeff Gilbreath, executive director of Hawaiian Community Assets, a nonprofit that provides financial literacy workshops, counseling and low-interest microloans. “If something is new or they don’t know about it, that can be a major barrier.” Gilbreath adds that, in many local communities, payday lenders are the only brick and mortar financial establishments. Plus, many payday lenders characterize the loans as a way to prevent the borrower from overdraft charges on her or his bank account. However, according to the Pew Charitable Trust, more than half of borrowers wind up over-drafting anyway.

It’s not hard to do when fees for payday loans skyrocket. In Hawaii, the law caps the interest rates payday lenders can charge at 15 percent of the loan’s face value which can be equated to 459 percent APR. For example, when Souza-Kaawa took out a $400 loan, she paid $60 in upfront fees, but, if she couldn’t pay it off in two weeks, she’d wind up owing $480 in fees after renewing it, plus the original $400. “In the long run it’ll hurt you,” she says. “You pay more in fees.”

This year, state Sen. Rosalyn Baker introduced a bill to cap payday loan APR interest rates at 36 percent. Both chambers of the state Legislature passed versions of payday-lending legislation this spring, but a final bill failed to come out of conference committee because conferees split over whether to cap interest rates. It wasn’t the first time legislative reform failed: In 2005, the Legislature stalled in passing regulations, despite the state auditor’s analysis that found that local payday interest rates commonly soar to nearly 500 percent. In 2013, an industry regulatory bill stalled in the House and last year a bill to cap interest rates was similarly killed in the House. Insiders say it’s likely due to persuasive industry lobbying, despite repeated testimony in support by nonprofits including Hawaiian Community Assets and FACE.

“It’s not only (like this) here in Hawaii, but around the country,” says Stephen Levins of the state’s office of consumer protection. “But when you have something that disproportionately impacts a large segment of our population in negative ways, something needs to be done. The easiest way of dealing with it would be to reduce the interest rate to a rate that would be manageable for someone to repay.”

Baker says she plans on reintroducing the bill next session. “My concern is not for industry,” she says, “it’s for the hundreds and thousands of families that are negatively impacted by these payday money lenders.”

WHY FINANCIAL LITERACY MAKES A DIFFERENCE

What if payday loans weren’t an option in Hawaii? People were still borrowing money before they sprang up. “They were still accessing capital, not necessarily at the banks or credit unions, but in a way that they could get short-term emergencies taken care of,” says Gilbreath. Several local families have told Gilbreath and the nonprofit’s six financial counselors that, prior to payday lenders, borrowers would go to their family or friends for small loans; some even went to their employers to ask for a pay advance or to withdraw from their 401(k).

Attaining economic self-sufficiency, particularly in the Native Hawaiian community, is the ongoing mission of Hawaiian Community Assets, established in 2000. The nonprofit serves roughly 1,000 families each year with offices on Oahu, Kauai and Hawaii Island through its budgeting and homebuyer workshops, and financial counseling.

When it comes to payday loans, the nonprofit educates borrowers about the often confusing and exorbitant interest rates, and presents alternatives. Borrowers begin breaking their debt cycle by attending one of the organization’s free, three-hour financial literacy workshops, where they learn how to track their expenses for one month, the importance of savings and understanding their income. (Harman says FACE refers its members to the nonprofit.)

After taking the workshop, participants are eligible for free financial counseling, which also includes pulling and reading credit reports. “When you put your spending down on paper, when you actually see it, that’s when it hits home,” says counselor Rose Transfiguracion. She helps dedicated clients qualify for the nonprofit’s match savings account to pay down debt, apply for one of its low-interest microcredit loans – thanks to funding from the Office of Hawaiian Affairs – or help them qualify for a fixed-interest loan at a credit union.

“Whenever I hear that someone is going to take out a payday loan, I try to educate them about better alternatives,” she says. Transfiguracion says she builds relationships with her approximately 100 clients by sharing her story. The Oahu native first become involved with the nonprofit after she and her husband purchased a home in the Kaupea Homestead in Kapolei.

Transfiguracion and Souza-Kaawa have been working together off and on for two years. They currently meet once a month in Nanakuli to discuss Souza-Kaawa’s progress. Thanks to her meticulous budgeting and dedication, she qualified her family for the nonprofit’s match savings account to erase her debt. As of press time, she’s brought the family’s debt down from $7,000 to under $1,500. Now Souza-Kaawa touts the nonprofit to all her friends and coworkers, some of whom have taken out payday loans, and offers some of her own advice, too. “It’s hard to change your habits and pay yourself first. But you can,” she says. “When I get my paycheck, my priority is my living expenses, then what needs to be paid off.”

WHAT HAPPENS IF A REFORM LAW PASSES?

When the Senate proposed capping the APR interest on payday loans at 36 percent, lenders, including Schafer of PayDay Hawaii, testified it would put them out of business. He says he does, however, support lenders registering with the state, as well as a “cooling off period” in which borrowers can’t take out a loan for seven days. “It isn’t the amount that we’re charging that creates the problem of paying it back, it’s other problems,” he says. “Some people are more budget conscious than others. Some people save money, some people don’t. If they had the savings they wouldn’t really need to use the product.”

Some payday lenders did close in states that imposed rates caps. For example, some payday lending businesses closed in Colorado after it capped its APR at 45 percent. However, according to The Pew Charitable Trusts analysis “borrowers’ access to credit in the state was virtually unchanged.” The state’s remaining payday lenders simply saw more customers.

Interestingly, most lending reform advocates in Hawaii don’t want to prohibit payday lenders, but all agree 459 percent interest is appalling and renders most borrowers unable to repay the loan. Souza-Kaawa says Easy Cash Solutions employees were always friendly, and even advised against frequent borrowing. In fact, Levins says, the state Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs has received few consumer complaints. But that’s not the point, he adds. “The issue is whether we want to allow a situation that is going to cause these social problems. I’m not saying most of these companies are violating the law, I’m saying there’s a problem with the law,” he says.

Ultimately, Gilbreath and Harmon say, tighter regulations force borrowers to seek other alternatives, from qualifying for a low-interest microloan, transferring to a credit union, or even borrowing from family and friends, and opens communication for nonprofits to educate borrowers on healthy financial planning.

Today, Souza-Kaawa views payday lenders as a last-ditch option for many families. “It’s there when you need it,” she says, adding that thanks to financial counseling, she’s become savvy to what she now describes as their “hideous” interest rates. “If don’t need it, don’t take out a loan,” she says. “Don’t go borrowing $500, just because you can.”

Souza-Kaawa continues to write out the family’s budget each payday. She has more exciting things to plan for now that she’s paid off most of her debt and uses payday loans less and less. “I can look toward the future,” she says. “Like saving for Christmas presents and maybe a family trip to Disneyland in two years.”