Overtourism and Crowding at our Favorite Spots

It’s Not Just Them, It’s Us

Not all the crowding at recreational and beauty spots is caused by tourists. Even residents are susceptible to the pressure to get out and post their jaunts on Instagram. Short-term residents like @stefanconey96, whose Instagram profile says he’s from Great Britain but plays tennis for UH Hilo, post photos of lush (and sometimes illegal) locales with captions like, “Never waste a day in Hawaii!” The hashtag #luckywelivehawaii is attached to 1.8 million Instagram posts, and many show people getting too close to endangered species or hiking forbidden areas.

“There’s a national trend of getting out and enjoying the open,” says Honolulu Fire Department public information officer David Jenkins. “It’s more than just visitors in terms of new people on the trail. There are new residents, people who just moved to Hawaii who are not visitors but still new to the island, and military personnel.”

And although visitors may flout trespassing signs or get themselves into dangerous situations, the DLNR’s Dan Dennison thinks that it’s not visitors who do many of the most destructive things, including staging raves at sensitive sites, vandalism and abusing native species: “A lot of the really egregious behavior that we’ve seen has largely been residents, to be honest.”

How to Fix It

The solution is not in placing some kind of cap on the number of visitors, industry experts say. At least not yet. “I have certain policymakers who say, ‘George, we can’t have any more people in my district!’ But I don’t have a switch that turns it on and off,” says Szigeti.

In the short term, we’re not talking about a single solution, but a bunch of solutions for challenges related to more humans doing more things in a confined space: to name a few, unpleasant crowding, eroding trails, decaying infrastructure, coral reefs that are harmed by the oxybenzones in many sunscreens. When looking at case-by-case solutions, Hanauma Bay – which limited the number of people a tour company can bring to the bay to six and introduced admission fees and a mandatory educational video in 1995, reducing the number of visitors by about 20 percent over a decade – is considered a success.

Stakeholders like the DLNR are starting to fight fire with fire, managing the damage facilitated by social media with tech tools, says Dennison: “We’re working with a couple of vendors to come up with a system to monitor social (media) based on keywords.” They’re also assigning a staffer to monitor metrics and respond accordingly, by shutting down unpermitted raves and parties and insisting that posts depicting illegal behavior be taken down. “I’d say we’ve been moderately aggressive in attacking it, and we’re about to get highly aggressive,” says Dennison.

“At the end of the day, you can’t keep people out. And if you’re not charging the proper price to mitigate congestion, then it’s not their fault. It’s your fault.”

Paul Brewbaker, Economist, TZ Economics

Visitor behavior can also be strongly influenced through education, says Bolan. Many visitors to Hawaii are not only coming for sun, sand and surf, which they can often get cheaper and closer to home; they’re coming for authentic culture and nature. “(Visitors) are not going to get upset if they’re given information like, ‘Welcome to Hawaii; it’s a special place, a sensitive destination culturally and environmentally, and these are the things we want you to know,’” says Bolan. Opportunities to educate start on the plane, which Bolan calls “a huge advantage” over other destinations: “I can’t drive to Hawaii. I have to be on that plane, and I’m given a form; it’s a chance to educate me.” Other opportunities happen at hotel check-ins, and even at the sites themselves, where the DLNR has been installing signs since 2015 with scannable QR (quick response) codes at sensitive locations to provide warnings and information.

One straightforward way to make sure tourism’s costs are factored into maintenance and management is to charge for open-access resources, as is already done at Hanauma Bay and Diamond Head. High operation costs and challenges with policing boundaries could at least in part be overcome with technology, says Brewbaker: “I’m oversimplifying, but surely there’s an app for that.” Two of many examples across the nation already in place: FastToll, the mobile app-based toll road system in Illinois, and the mobile app to pay for entry now being piloted at Joshua Tree National Park in California.

“The tourists will still come, but at least some form of compensation has been designed so that the decision they’re making to go down to rent a kayak in Kailua Beach and paddle up to the Mokuluas and look at the bird sanctuary, is undertaken with an explicit cost associated with the use of a public, recreational open-access resource,” says Brewbaker. “Everywhere else charges. Only Hawai‘i doesn’t.”

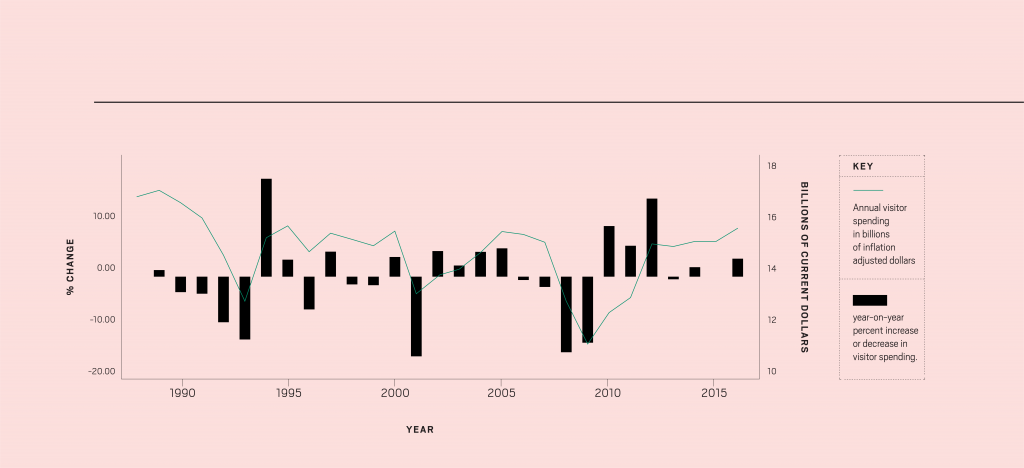

ANNUAL VISITOR SPENDING IN BILLIONS OF ADJUSTED DOLLARS: Visitor spending, when adjusted for inflation and expressed in constant 2016 dollars, represents a strong recovery from the Great Recession, but has never reached late-1980s peaks.

(Source: data.uhero.hawaii.edu/#/series?id=164719&sa=true)

And the fees shouldn’t necessarily stop at individual users. Brewbaker says that tour operators who conduct their business by relying heavily on open-access resources should also pay to play: “‘Oh, but it’s a public park?’ That’s not public, it’s a private, commercial enterprise. It’s not me taking my family. Why is it not obvious that a private, commercial user for a public recreational resource should be paying for the right to use that resource? At the end of the day, you can’t keep people out. And if you’re not charging the proper price to mitigate congestion, then it’s not their fault. It’s your fault.”

After that, the thing to do, says UHERO’s Bonham is to make sure the revenue generated is used to restore and create resilience in the resources being depleted, which he says has not recently been the case, at least for public infrastructure. “It’s one thing if you have a robust visitor industry that is generating tax revenue, as it is, and you’re spending a share of that revenue to maintain that natural environment and maintain the facilities – the airport, parks, roads, everything. That’s as it should be. But we don’t seem to be able to do that,” says Bonham. “I have a hard time thinking of any beach park bathroom facility in the whole state that I’ve ever been in, in 30 years of living here, that I would say is acceptable. When you compare those facilities to facilities in other states, it’s really mind blowing.”

Another possibility is to take advantage of underutilized capacity by encouraging more tourism on the Neighbor Islands, a strategy that is rolling out now, with most of United Airlines’ 400,000 additional Hawaii air seats being direct from the Mainland to the Neighbor Islands. Hawaii Island and Kauai are projected to increase their air capacity by more than 20 percent during November 2017 to January 2018, over the same period a year ago, moves that Szigeti says will lead to “a little more balance between all the islands – that balance is really important.” He acknowledges that balance also needs to come with a real conversation about the increased stress placed upon environment, infrastructure and residents on those islands.

In the long term, if Hawaii is to be a resilient destination, a wider view of the costs and benefits of tourism is needed, says Bolan. “There are the traditional numbers: ‘How many come? How long do they stay? How much do they spend?’ But how much (money) is staying local? How widely is it being distributed? How is it being invested? And at the same time, what is the true negative impact? Travel and tourism are fun, but there is also coastal erosion and waste and water and social impact.”

That increased scope of information needs to come in a usable form, he continues: “There’s no line on the profit/loss statement that says, ‘I paid $5 to the ocean because I went kayaking,’ since I might have put sunscreen in there. If you can’t quantify the negative of what you’re doing, no one’s going to pay for it. We need to use data to persuade parties to do a better job.”

Getting the right data by asking the right questions is tough but important, agrees Mak. “You trace the tourism dollars and find out who gets what. It’s not easy, but it’s doable. Even if we do get ballpark estimates or ideas about … the people who are left behind by all of this, we can find ways to improve the distribution of the benefits of tourism.”

And then we need to ask the big question, says Bolan: “What does Hawaii want to become?” We think of ourselves as a mature tourism destination, but the reality is always changing, and our models and approaches must change along with it.

For that, says Szigeti, a multi-stakeholder dialogue is necessary. HTA gets the brunt of tourism complaints, but there’s only so much it can do, he says: “One person, one entity, one group is not going to have an answer to all these challenges. It’s going to be everyone having to come together. And that’s going to take time.”

We’re All Tourists Now

Something Atladóttir said that stuck with me was that in a world where travel is considered a standard part of life, which she called “the biggest societal change since the industrial revolution,” each of us plays every role. We will all, at some point, be the residents rubbed the wrong way by visitor incursions, but we will also, at other points, be those visitors ourselves.

So this is less a tourists vs. residents scenario, than a win-win, or lose-lose, situation – and if Hawaii can get it right, everyone will benefit. The upsides to well-managed tourism are enormous, said Atladóttir: “We just have to figure out where we are, where we want to be and how we are going to get there.”