Overtourism and Crowding at our Favorite Spots

Tragedy of the Commons

It can also lead to outcomes no one wants. One phrase that keeps popping up with respect to what’s happening with global tourism today is “the tragedy of the commons.” It sounds Victorian, and for good reason: It’s an old economic concept that originated in Britain, where some of a town’s land was often held in “common” so everyone in the community could graze their animals on it. But common resources only work when everyone who uses them also helps to steward them in some way. Otherwise you get the tragedy part – where individual users act only in their self-interests, using the resource for themselves before others can deplete or spoil it faster. “If you have a free good which is limited, your incentive is to take as much as possible before others get to it,” says Mak. “Eventually, if you all behave in the same way, the asset is destroyed.”

In Hawaii’s case, our common resources are both natural (healthy oceans and shorelines, unique flora and fauna) and human (everything from infrastructure and open space to culture and interpersonal trust). Hawaii is “totally” facing a tragedy of the commons, says Geoff Bolan, executive director of Sustainable Travel International. “In Hawaii, if you go to a park or a nature reserve, there might not be an entrance fee, but there’s still impact. And it isn’t necessarily just an environmental issue. It’s also, ‘Why are there so many people walking around by my home?’ The ‘commons’ there is the sidewalk.”

The problem, says Bolan, is not just individual visitors, but also private enterprises that are incentivized to use a public resource, whether it be a beach, a trail or a sidewalk, as extensively as possible while charging clients for access, knowledge, services and equipment. “A hotel or a resort or a tour operator, they’re extracting (from), making money off, that resource. That’s fine – but honestly, are they putting their 2 cents back into it? Should locals just have to deal with it – traffic and parking and annoying or insensitive behavior? I would say there’s a large imbalance in Hawaii and many other places.”

Tourism’s Changing Role

Although spending per visitor is up, tourism’s economic benefits relative to its cost have gone down over the course of a generation. Statewide tourism receipts look to be reaching record highs, but adjustment for inflation finds that the industry actually brings in less than it did at its peak in 1989. “Tourism has been shrinking as part of the Hawaii economy measured in real dollars. People don’t talk about that, but it is a fact,” says Mak.

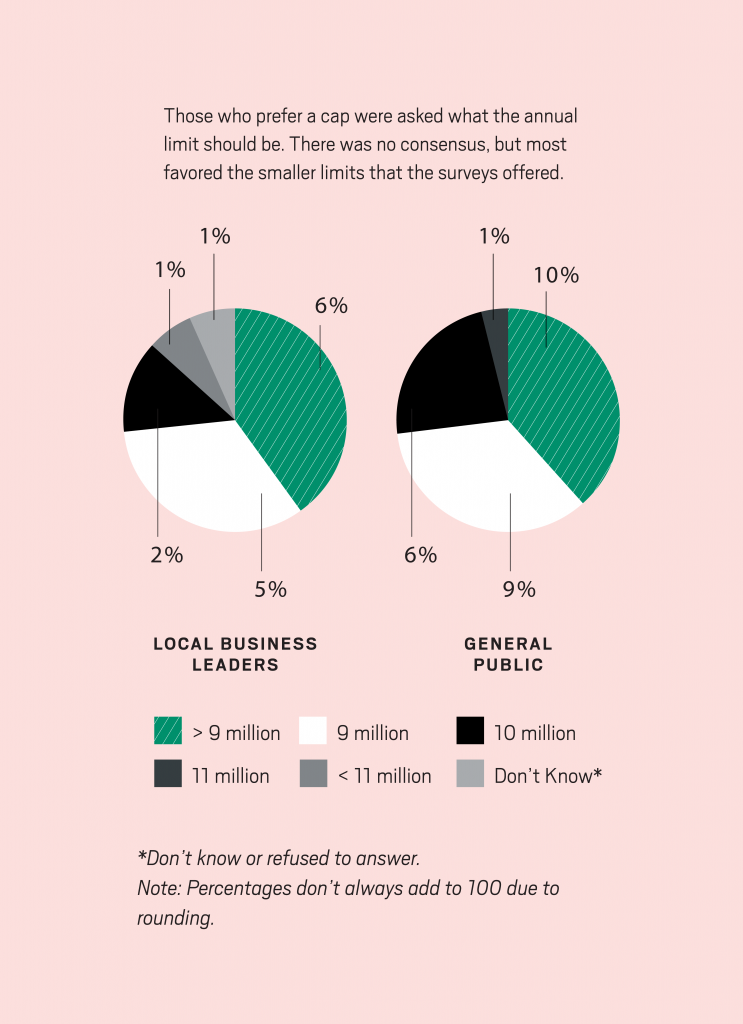

“It’s not that we don’t like 9 million people,” agrees Brewbaker. “It’s that when there were 7 (million), we made $18 billion off them, and now that there are 9 million of them, we make $16 billion off of them (after adjusting for inflation). Straight off the top, more pilikia for absolutely less money. How is that good math?”

Tourism has also been shrinking as a percentage of Hawaii’s economy. Brewbaker wrote in a white paper produced for Hawaiian Airlines that tourism “declined from approximately 25 percent of gross (Hawaii) product in the mid-1990s, to approximately 15 percent of gross product in 2010, rebounding to an estimated 17 percent of GDP in 2012.”

The stakes are twofold. First, if lines are longer, crowds are larger and foot and vehicle traffic are higher, all in an environment that wasn’t built to handle these numbers, quality of life for local residents is diminished. Pointing out the economic benefits of tourism isn’t enough to preserve aloha spirit, says Atladóttir: “I can throw statistics at (people) about the economic benefits and the unemployment rate until I’m blue in the face, but they’ll just go, ‘Yeah, but I couldn’t get a seat at my café this morning, and I’m pissed off. This is too much.’”

Also at risk is the visitor industry itself, because the welcome that visitors receive from locals has always been key to a destination’s reputation. “If you’re not getting the warm looks and welcome from the locals, what does that mean?” says Bolan. “At some point, this common asset does come back to haunt you. It’s not today and tomorrow,” he says, but it’s someday.

Mak points out that since 2005, more than half of Hawaii residents have agreed with the statement on recent HTA surveys, “This island is being run for tourists at the expense of local people,” and that other indicators of resident satisfaction with the tourism industry are also slipping. “If we don’t do anything about it, I think the surveys speak for themselves,” says Mak. “More people in Hawaii now think the state is run more for the benefit of tourists than for locals. That would be dangerous for us. It would result in erosion of the aloha spirit” – the same aloha spirit that Szigeti calls “the key ingredient that separates us from other sun-sand-surf destinations.”

But Mak and Brewbaker don’t think visitor numbers should stagnate or shrink. Brewbaker points out that “tourism is to Hawai‘i as petroleum is to Saudi Arabia and high technology is to Silicon Valley,” and describes it as “the reason for Hawaii’s modern economic success.” “It’s our economic engine,” says Szigeti, from his office in the Convention Center. “I ask everybody to look out that window and tell me who our No. 2 (industry) is.”

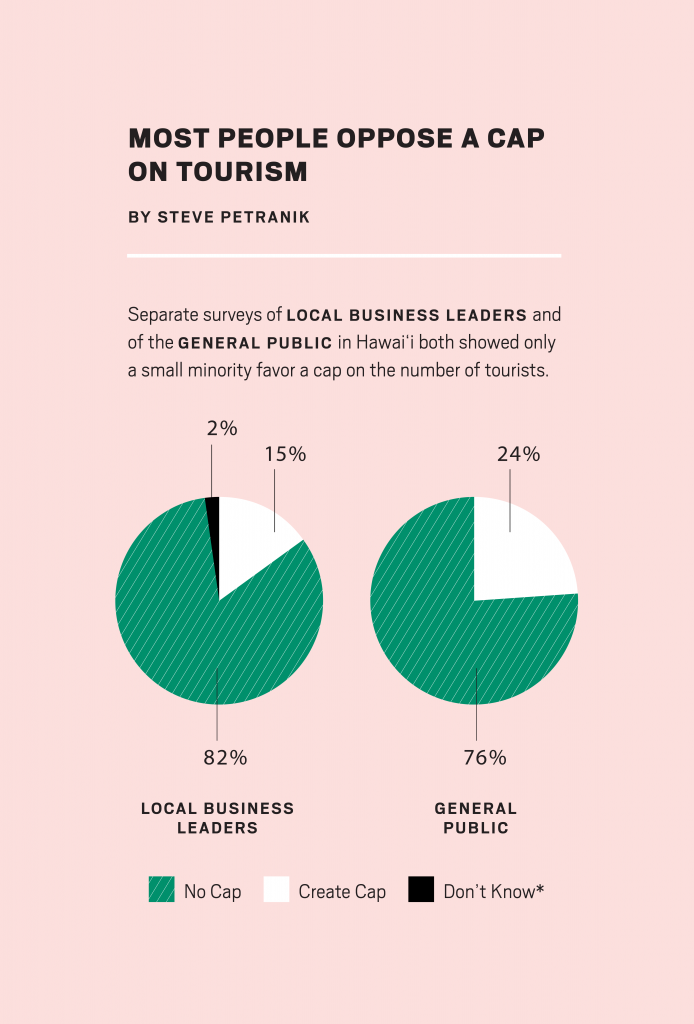

Methodology:These responses were part of two larger surveys conducted by Anthology Marketing Research for Hawaii Business in the fourth quarter of 2017. The BOSS survey reached 402 local business leaders by telephone statewide; the Island Issues survey reached 466 residents by telephone and internet.

The visitor industry provides not only jobs and GDP, but also facilitates the excellent domestic and international air access that Hawaii residents see as essential to life on the rock. And unlike many other industries, tourism depends upon and supports cultural uniqueness and natural beauty, two things that enhance resident quality of life, too. Brewbaker, like most of his colleagues, argues for smart management instead of constraints on growth, and urges leaders not to “equate sustainability with restrictions on tourism capacity.”

In fact, although everyone I spoke to acknowledged that at some point the visitor/resident ratio can become overwhelming no matter how well the visitor industry is managed (Venice, for example, has 55,000 residents and 30 million visitors annually), no one who has studied the issue said Hawaii was near that absolute limit. But there was a pervasive sense that our old model of designating tourist districts – which still works well for places like Las Vegas, whose 43 million tourists stay mostly on the Strip while its 600,000 residents largely live, work, and play elsewhere – had been rendered obsolete in the past two decades.

We need a new approach.

DLNR QR code on a hiking trail educational sign