One Family at a Time

Three nonprofits on Oahu are partnering with needy families to build affordable homes for ownership using the beneficiaries’ sweat equity, plus volunteer labor, government help, private donations, and a whole lot of advice and support for the families. All that effort only goes so far: In 2016, the three nonprofits completed building two houses in total and currently have four more in the process of construction or rehabilitation. But they believe they have momentum and partnerships that will yield more homes in the near future. With each success, comes more than four walls and a place to sleep.

The Santos family partnered with a nonprofit called Mustard Seed Miracle to build their home in Waimanalo. From left are Rusty Santos, Noa, 9, Isaiah, 2, and Kinohi “Ola” Santos. Photo by Josiah Patterson.

“In building a house, we are rebuilding relationships. Community home building reknits social fabric,” says Peter Kang, VP of Mustard Seed Miracle, one of the three nonprofits that creates “community-built housing.”

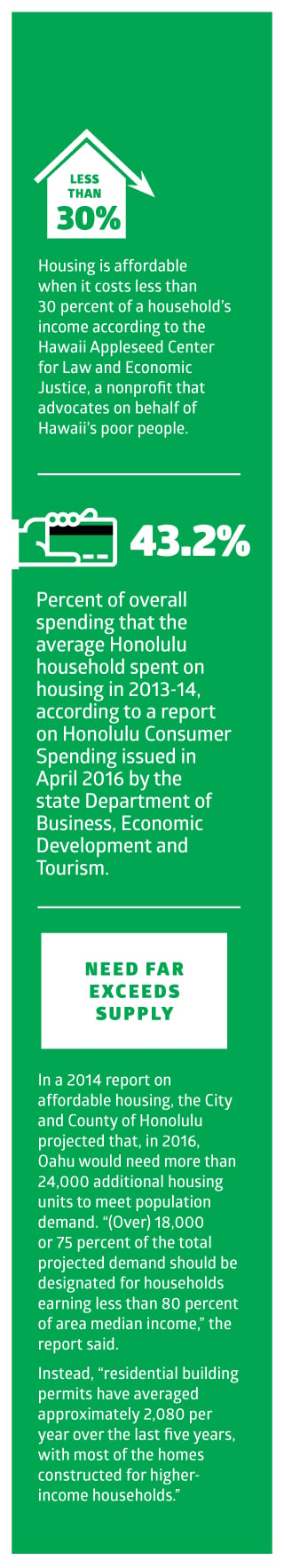

The first and biggest hurdle to building an affordable home for ownership on Oahu is the high cost of land, says Jim Murphy, executive director of Habitat for Humanity Honolulu. “I am one of the few Habitats in the nation that doesn’t have enough money to lend to clients to buy land,” he says. Most Habitat branches in America offer clients interest-free loans they can use to buy land. The prohibitive cost of real estate makes this impossible for Habitat Honolulu. Consequently, Murphy explains, “The families on Oahu we help largely already have property. They may be living on it and need their existing homes to be demolished.”

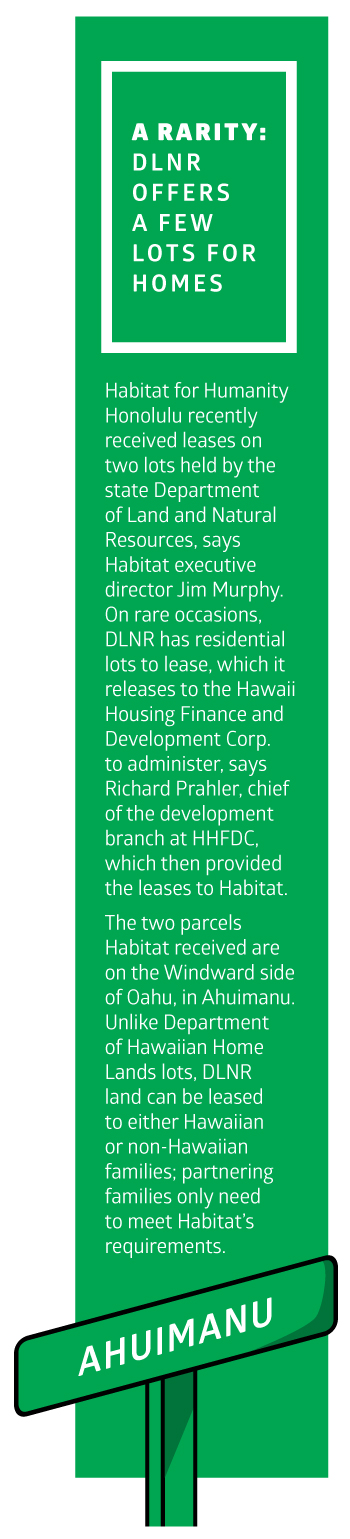

The three nonprofits – Habitat Honolulu, Mustard Seed Miracle and Habitat for Humanity Leeward Oahu – rely on the state Department of Hawaiian Home Lands to provide free lots. On Oahu, in Kapolei and Waimanalo, DHHL has vacant lots committed to beneficiaries with Native Hawaiian blood quantum of at least 50 percent and whose annual income is 80 percent or less of the area median income.

The three nonprofits – Habitat Honolulu, Mustard Seed Miracle and Habitat for Humanity Leeward Oahu – rely on the state Department of Hawaiian Home Lands to provide free lots. On Oahu, in Kapolei and Waimanalo, DHHL has vacant lots committed to beneficiaries with Native Hawaiian blood quantum of at least 50 percent and whose annual income is 80 percent or less of the area median income.

To make affordable homeownership possible, each of these nonprofits relies upon a complicated constellation of affordable housing programs. The process usually begins with DHHL granting lots to the nonprofits. Once land is available, the nonprofits’ next step is to find a family willing to be a partner. Local foundations and nonprofits help find qualified and willing families, and then assist them with financial education and home maintenance.

To help families pay for building materials for DHHL lots in Waianae and Waimanalo, the U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural Development (USDA) offers collateral-free mortgage loans to families with 80 percent or less of the area median income (AMI); the loans can be used to build, rehabilitate, improve or relocate a home in eligible rural areas. USDA Rural Development will back up 90 percent of these loans in case of default. The process of preparing the family to apply and qualify for a loan takes time.

“I don’t want them to start the process and then realize that a $300 mortgage is going to leave them strapped for cash, having to sacrifice medicine or education. If that’s the case, they’re better off renting,” Murphy says. Kang concurs: “Getting the right families to work with is the key. They need to be ready before, during and after the house is built.” To help educate new homeowners, Kang and Mustard Seed Miracle work with Partners in Development Foundation, a nonprofit that uses Hawaiian values and traditions to mentor families and teach them personal finance. The foundation also requires that families put in 500 hours of sweat equity into building their own home.

Art Hansen founded Mustard zSeed Miracle, a nonprofit that helps low-income families build homes of their own. The name comes from a passage in the Bible, which likens the Kingdom of Heaven to a tiny mustard seed that grows into a giant tree. Photo by Josiah Patterson.

Terry George, president and CEO of Castle Foundation, believes that successful affordable housing for ownership requires placing families within a community where they can thrive. In the late 1990s, George served as the chief program officer for the Consuelo Foundation. At the time, the foundation worked with families in Waianae to build their own homes. Over nine years, George explains, these families constructed 75 homes on a vacant 14-acre lot.

The foundation hired people born and raised in the community to prepare applicants for home ownership. “We had to know how they were doing on child support. If we were taking on a guy who had payments, we needed to make a plan for paying any existing child-support arrears,” George explains. One of the counselors they hired was a woman from Waianae, who was actually rejected by USDA Rural Development because she had too much debt, to teach families how to live a debt-free life. She would explain that, when clients bought a new truck with no money down, they were actually getting $30,000 more in debt.

The foundation provided basic financial education. “This is very important so they could qualify for a low-cost mortgage,” says George. “Trust and mentorship takes time, you’re working with families one by one; it’s individual blocking and tackling. Counseling is just as important as a building inspector or a loan officer. Banks don’t have time to do this. Some people, not all, get a little behind. And, if this happens, you’ve got to get to it right away. People cannot be in denial or embarrassed. You can save the mortgage if you have that relationship of trust. That is the special sauce of success.” Consuelo Foundation focused on further strengthening an existing community, and Habitat for Humanity Leeward Oahu shares this approach.

“You have to stay in your own area,” explains Jo Bautista, executive director of Habitat Leeward. Her organization’s mission is to eliminate substandard housing and homelessness from Ewa to Waianae. Bautista notes that, because there are few big businesses in her area, she has learned to be resourceful with “the little bits and pieces that (we) receive. We’re tiny, but we do good stuff.”

“You have to stay in your own area,” explains Jo Bautista, executive director of Habitat Leeward. Her organization’s mission is to eliminate substandard housing and homelessness from Ewa to Waianae. Bautista notes that, because there are few big businesses in her area, she has learned to be resourceful with “the little bits and pieces that (we) receive. We’re tiny, but we do good stuff.”

Since 2005, Habitat Leeward has built 10 homes and rehabilitated one. Currently, the nonprofit is building one new home and expects to soon have permitting to start a rehabilitation project. On average, Leeward Habitat spends $125 to $130 per square foot to build homes and relies on 15 to 20 volunteers to help with the builds.

Bautista’s greatest need and hurdle in building a home is securing loans. “If I had money to spare, then we’d make the 0 percent interest loans ourselves.” Bautista continues, “If I didn’t have to rely on USDA for a loan and I’m not waiting for anyone, the longest (hold up) would be the permitting. And we now have third-party review people (to expedite permitting).

“USDA is the only game in town. Because of USDA loan requirements, we can only help qualified families who are at 80 percent AMI. If we could have more access to capital, we could build. There are empty lots just sitting there. USDA, they’re doing their part, they’re getting to people on the list, but if the family doesn’t have the funds, we can’t build.”

The entire process, from gathering documents, to completing loan applications, to receiving approval takes a year. “It’s no one’s fault,” Bautista adds. She wishes that Hawaii had its own nonprofit that provided zero-interest loans like the USDA does. If that were the case, explains Bautista, Habitat Leeward could build more houses for qualified families far faster.

Despite the challenges, she remains undaunted: “We get by. God carries us everywhere. We make a difference, but only because we have a lot of heart. You do the best that you can. You’ve just got to be patient.”

Kang believes that, with community-built affordable housing, “social architecture is more important than physical architecture.” Social architecture includes families reaching out to extended family members to ask for help putting up drywall or helping someone start the application process for DHHL land. Kang, along with architect Art Hansen and Tim Shaw, a pastor at First Presbyterian Church of Honolulu at Koolau, started Mustard Seed Miracle in September 2015.

It does not independently raise funds to build a house, explains Shaw. Instead, the nonprofit helps “indigenous organizations come together from within the Hawaiian community to address the need for affordable housing for the working poor.” Shaw continues, “Each organization brings in a specific area of expertise. Each one has a love for the Island. No one organization is trying to do everything.”

Volunteers prepare a home site in Kapolei. Among the workers on the construction project are members of the Kaliko family, shown at right, who have partnered with Habitat for Humanity Leeward Oahu. The family will own the Kapolei home when it is done. Photo by Josiah Patterson.

This past September, Mustard Seed completed its first project, a 1,600-square-foot, five-bedroom, two-bath home with a carport and lanai in Waimanalo. The total cost of construction was $115,000 or about $72 per square foot. Kang attributes Hansen’s design as a huge factor in keeping construction costs down. It took the family nine months to qualify for a loan and eight months to get permits from the city.

This past September, Mustard Seed completed its first project, a 1,600-square-foot, five-bedroom, two-bath home with a carport and lanai in Waimanalo. The total cost of construction was $115,000 or about $72 per square foot. Kang attributes Hansen’s design as a huge factor in keeping construction costs down. It took the family nine months to qualify for a loan and eight months to get permits from the city.

“We worked two days a week with some extra days here and there,” explains Kang. “Saturdays are our main workdays, which would last eight hours. We’d spend six hours every Wednesday prepping for the weekend.”

Kang estimates that the build took about 7,000 hours total with approximately 20 revolving volunteers. In moving forward with the next project, Kang acknowledges it is a slow process. “There are so many choke points: from getting a family ready, to loans, to permitting, to bad weather, to working with volunteers who have full-time jobs.”

Habitat for Humanity Honolulu knows the importance of establishing a social foundation and the cost of having to rebuild its network. When Murphy was hired in August 2013, he was the organization’s fifth executive director in eight years. The high turnover, as Murphy describes it, “had taken its toll on housing, efficiency, relationships. You name it, we were doing it wrong.”

Murphy credits the Habitat Honolulu’s board of directors for giving him the time and authority to clean things up. “When I came on, they were in the process of building five houses. Four months after I started we finished them. It took us everything (to complete the homes).

Volunteers from across Oahu rest while installing siding on a new home in Waimanalo. Jim Murphy of Honolulu Habitat says the home is scheduled to be completed in April for a Native Hawaiian woman, who is the single mother of three children.

The guys that were building it – when they were done – we shook hands, said goodbye, and completely restructured the building program.”

Habitat Honolulu says it didn’t have the contractors it needed. “People here deserve quality homes,” says Murphy. “I knew we could do this better and more efficiently.” To manage projects, Murphy hired Mel Ressler, who had eight years of experience working for Habitat in North Carolina, to organize and direct unskilled volunteers. Murphy says, “It was easier to hire from the Mainland. Here in Hawaii, if you’re good at what you do, you’re already doing it and getting paid a lot of money to do it. She came in, put her arms around the organization and ran with it.”

In 2016, Habitat Honolulu completed one home and had two under construction. “We are currently building a two bedroom for $218,000 and a four bedroom for $236,000. I usually use the (cost) range $175 to $225 per square foot when I talk in introductions,” Murphy says.

Over 500 volunteers donate a total of 4,000 hours of work to help build each new home. “Our goal is to get somewhere between six to 10 houses a year,” Murphy says. “We can do this, but, to do so, I need to raise money and awareness.” Among the limiting factors to ramping up, is that “a lot of people don’t know about us. Getting that local brand has been my biggest focus. If no one knows about us, then I can’t get people to believe in what we’re doing and why we’re doing it.”