Nonprofit Boards: Confused or M.I.A.

“When I look back on it,” says John D., the former executive director of a small but prominent nonprofit in Honolulu, “the board of directors just really didn’t understand what their role was.” He pauses for a moment, his face assuming a pained expression. “In some cases, they made their job more difficult by micromanaging the staff. But they also didn’t take care of their basic responsibilities, like raising funds or strategic planning. In the end, they made it impossible for me to do my job.”

His is a common sentiment among the leaders of Hawaii’s nonprofits, particularly those from small- and mid-sized organizations. Many executive directors, CEOs and even some maverick board members say privately that their boards are poorly prepared, misinformed and often burdened with damaging misconceptions about their roles. The result is a lack of clarity about the relationship between the board and the executive director, and about their respective responsibilities. Inevitably, this confusion leads to conflict and limits nonprofits’ effectiveness. And if you listen to Hawaii’s community of executive directors, it’s the boards of directors that are mostly to blame.

It’s true, some nonprofit experts are more circumspect. For example, Holly Henderson, who, as executive director of the Weinberg Fellows and Castle Colleagues, has helped train hundreds of executive directors and board members in Hawaii, believes these problems are an inevitable part of the evolution of a nonprofit. “What I see a lot of,” Henderson says, “are boards that aren’t working anymore. And although there are individuals who want to blame somebody, sometimes it’s just the same as blaming a kid of for growing out of a pair of shoes. Because, what works at one point in an organization’s life doesn’t work at another point. And it’s not necessarily anybody’s fault.”

She also notes that business people make up the bulk of nonprofit board members, and that they’re volunteers, often taking valuable time away from their companies and families. “You have people who want to help the community by volunteering their time,” she says, “and they’re not happy to be told they’re not doing a good job.”

Holly Henderson, who helps train nonprofit leaders, says conflicts arise when nonprofits evolve, but their boards do not change with them. | Photo: Rae Huo

Henderson’s perspective draws on the work of the nonprofit expert Karl Mathiasen, who divided nonprofits and their boards into three stages of development:

- Small, informal “organizational boards,” dominated by the nonprofit’s founders;

- Larger, more independent “governing boards” that begin the process of formalizing rules and procedures; and

- Large, sophisticated “institutional boards,” replete with standing committees and many of the attributes of a for-profit corporation.

According to Mathiasen, these transitions, particularly from an organizing board to a governing board, are often fraught with conflict. To make matters worse, as Henderson points out, executive directors and board members may evolve at different rates. This, she says, is why so many executive directors complain about their boards.

To some extent, it was always so. Several years ago, the Hawaii Community Foundation did a survey of executive directors to understand why turnover was so high among nonprofit leaders. “The No. 1 complaint that came out was the board,” says Christine van Bergeijk, the foundation’s vice president for programs. “There was really a great deal of sentiment that executive directors were all by themselves, and the board members were merely cheerleaders. The EDs said they needed the board to roll up their sleeves and do some of the hard work.” Board members, in other words, aren’t living up to their end of the bargain.

Of course, that’s only one side of the problem. Executive directors, for example, deserve a share of the blame. Many, particularly if they founded the organization, preserve their power by keeping their board members in the dark. And there’s a whole other story to be told about the level of professionalism among the leaders of the nonprofit community. So, the incompetence of board members isn’t the only problem facing nonprofits. “It’s true that our board is kind of passive,” says a board member from a small educational organization, “but I think the members would work with the executive director if she really needed help.”

It’s certainly telling, though, that although many executive directors were willing to share their complaints, none were willing to do so on the record, citing a fear of reprisals from their board or the inability to get nonprofit jobs in the future. Many also worried that public criticism would damage their ability to raise funds. For that reason, we’ve disguised the identities of most of the executive directors cited in this article as well as the organizations they run. Of course, this anonymity makes it difficult to gauge the validity of their complaints. But the striking uniformity of their criticism gives them credence.

For this story, we interviewed the executive directors, staff members, and members of the boards of more than a dozen nonprofits. We also spoke with some of Hawaii’s most respected nonprofit experts and consultants. Over and over, they brought up the same tales of board members who didn’t understand their roles or failed to embrace their responsibilities. Here are the three major areas where Hawaii’s nonprofit boards come up short:

Board Development

“All my board members are just friends of one another. For ‘board orientation’ all they get is a pat on the back and a copy of our last annual report.”

—Noelani K., executive director of a social services provider.

“Too often, board members treat meetings like a social club. They don’t seem to take the work or the mission seriously.”

—Tom K., executive director of a nonprofit intermediary organization.

“We’ve had the same chairman of the board for 10 years.”

—Mary N., CEO of a cultural organization.

“The board members absolutely refuse to attend any kind of board training. Even though none of them have any experience, they all say they already know everything there is to know about how to run a nonprofit.”

—Amy L., executive director of an environmental organization.

It starts by picking the right board members. All too often, executive directors complain, new members are selected because they’re friends of other members. Except on some large institutional boards, little strategic thinking goes into identifying candidates and courting them to see if they’re a good fit. The result is often undersized, homogeneous boards that lack the skills needed to govern an organization responsibly.

This also poses problems for potential board members. For business executives contemplating joining the board of a nonprofit, it’s not simply a matter of whether you want to serve, but whether you’re a good fit. Amy Hennessey, a former board member for Community Links, a Honolulu organization that served as a sort of incubator for nonprofits until it closed earlier this year, says that means asking questions. “You want to ask about their expectations: ‘What’s your fiscal structure? Are you in financial difficulty? What’s your plan for the future? What are your expectations for my involvement on this board? How much of my time do you really need? In other words, what do you need from me in terms of time, money, intellect – all that?”

Of course, those questions rarely arise from new board members. Even worse, board members, even after they’ve been selected, are rarely told what’s expected of them or given an adequate orientation to the board’s duties. And, as one executive director pointed out, “There’s never any discussion of the division of labor between the board and the ED.” Clearly, there needs to be a more thorough education of board members.

But, as Henderson points out, board members aren’t necessarily going to embrace this education. “These are often prominent people,” she says. “A lot of them don’t take well to the idea that they need training. In fact, I rarely use the word ‘training’; I usually say ‘briefing.’ ” Whatever you call it, though, board training should be an ongoing process, not just for new members. Henderson gives the example of board rotation, the use of term limits to systematically replace board members. “One of the wonderful things about board rotation is it gives you the opportunity to get the board together and to do some orientation. Ostensibly, it’s for new board members, but long-serving board members can hear it as well.”

In most cases, though, there’s little or no orientation, and both executive directors and board members can share in the blame. “What I’ve seen a lot of, over the years,” says Robbie Alm, “is a failure on the part of everybody – executive directors, board members, board chairs – to really work out and understand what their roles are. It’s almost as if we assume we know, so we never really talk it out.” In the nonprofit literature, this is sometimes referred to as “blurred roles.” A board member from one local nonprofit put it another way: “Nobody knows a damned thing.”

Not everyone believes that boards are the problem. Tim Johns, CEO of Bishop Museum, for example, says there’s been a trend toward more and better training, so board members today have a better understanding of their roles. (It’s worth noting, though, that most of Johns’ board experience has been on mature, institutional boards.) He does note, however, that the pool talent in a community of this size is limited. “We do have a lot of nonprofits, so we may not have as many potential board members as you have in a larger community.” As a result, he says, people might be sitting on boards earlier in their careers. “If you were in San Francisco or Chicago, you might not be sitting on that type of board at that point in your career.”

Robbie Alm, VP at HECO and a member of several nonprofit boards, says most boards offer only a basic orientation for new members. | Photo: Olivier Koning

Fundraising

“When I started our first capital campaign, my board chair said to me, ‘Why do I have to fundraise, isn’t that why we hired a development director?’ ”

—Mary N., CEO of a cultural organization.

“When I tell the board that funders often require 100 percent board participation, they say, ‘Isn’t our time enough? We’re all professionals; our time is worth something.’

—John D., executive director of a human services agency.

“Several of my board members actually told me they would never ask their friends to support our agency; it would be too embarrassing.”

—Amy L., executive director of an environmental organization.

“Our board chair said flatly he won’t donate, won’t raise funds, and won’t quit.”

—Mike T., CEO of an arts group.

Money is king. And for most nonprofits, fundraising is the single most important responsibility of the board of directors. That’s because it almost always takes cash for organization to accomplish its mission. It’s true that board members are often recruited for other reasons – financial or legal skills, for example, or cultural or technical knowledge – but these attributes are rarely sufficient. A board member’s time and talent are useful, of course, but they don’t pay the rent or insurance, they don’t cover the salaries and benefits of employees, and most importantly, they don’t pay for food for the hungry, educational programs for the environment, medical treatment for the sick, or any of the countless other programs that fall within the missions of Hawaii’s nonprofits. That takes cash, says van Bergeijk of the Hawaii Community Foundation. And it’s the board members’ role to donate or, better still, raise that cash from the community.

“I think the prevailing expectation today,” van Bergeijk says, “is that, if you’re on a board, you must make sure the organization has the resources they need to do the job. That equals fundraising. It shouldn’t be only fundraising, but that’s the prevailing expectation. If you’re on a board, you’ve got to help raise money. And not everybody’s cut out to do that.”

This judgment is nearly universal among nonprofit professionals. And yet the board members of many nonprofits often fail to participate in fundraising in any meaningful sense, leaving it to the executive director or to one or two more committed board members. Christine Valles, a member of numerous nonprofit boards herself, and owner of Silver Lining Consulting, a company that advises nonprofit organizations, believes this problem, like many of those facing nonprofit governance, is another outcome from how board members are recruited in the first place. No one tells them what’s expected of them.

“It has to be clear to the new board member that they’re responsible for fundraising,” Valles says. “That’s universally agreed upon in the nonprofit world. They have to provide some means for the financial stability of the organization. But that part is really underplayed when board members are recruited. No one takes the time to say, ‘You know, you’re going to have to take the lead at raising money. You’re going to have to make a personal donation, and you’re going to have to ask your friends for their support.’ Even though that’s simply saying what boards do. You’ve got to say, ‘As board members, we’re all responsible for fundraising. So if you’re not actively asking people to give money, you probably shouldn’t be on a board.’ ”

This reliance on the board for fundraising isn’t universally true. Many organizations that provide social services, for example, rely mostly on government contracts for their funding. Other nonprofits depend largely on grants, either from government sources or from private foundations. And because the agency staff usually writes and prepares grant proposals, that relieves the board of some of its responsibility to raise funds.

It’s worth noting, though, that many private foundations and wealthy individuals will not support an organization unless every board member has contributed money. And the vast majority of Hawaii’s 6,000 or so 501.c3 nonprofit organizations depend on financial support from the community for their survival. In some ways, that’s the theory of having a board in the first place: to provide a link to the community, a way to ask the public for its support.

At large nonprofits with institutional boards, this concept is generally (though not universally) understood. One of the reasons the boards of organizations like the Aloha United Way or the Easter Seals are so large (Easter Seals Hawaii, for example, has more than 30 board members) is to spread out the burden for raising funds. In fact, new board members are often selected as much for their ability to attract financial support as for any contacts or skills. This is why most institutional boards try to attract bank executives as members. Robbie Alm, vice president of Hawaiian Electric Company, and a board member for more than 20 nonprofits over the years, points out that senior business executives recruited this way usually understand their role.

“Certainly, many of the large nonprofits are very deliberate in their efforts to do that,” Alm says. “And it works. If I agree to go on the board of an organization, not only am I going to give, but most likely my company will have a table at that fundraiser dinner, that we’ll be at that luncheon or attend that ball.”

The problem is that the board members of smaller and mid-sized organizations often fail to make that assumption. These nonprofits are frequently stuck at the organizing board stage of their evolution, and their members are either unable or unwilling to actively raise funds.

The solution is clear. Executive directors say their nonprofit boards need to be much more engaged in the organization’s fundraising. Members should donate according to their means and actively solicit donations from their friends and contacts. Holly Henderson offers perhaps the best advice for potential board members: “Pick an organization doing something you’re passionate about. That way, you won’t feel uncomfortable asking people to support its mission.”

Oversight

“We’re not responsible for the financial filings, we’re just an advisory body.”

—James K., board chair of a cultural organization.

“The board has always refused to pay for an independent audit of our finances.”

—Donna T., board member of a community development organization.

“The ED of my former agency never filed a grant report on time, and used the agency’s accounts like a personal slush fund.”

—Tom G., staff member at a Honolulu social services organization.

Most nonprofit boards understand that they’re responsible for oversight of the organization. The problem is that, all too frequently, they believe this is limited to hiring and firing the executive director. In fact, their oversight responsibilities are more comprehensive. For example, it’s the board, rather than the executive director, that’s legally liable for much of the financial regulation of the organization.

Partly, this is the result of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, Congress’s response to scandals at Enron and WorldCom. “Even though it was primarily targeted at publicly traded companies,” says Anna Elento-Sneed, an attorney at Alston Hunt Floyd & Ing specializing in nonprofit law, “there’s a section that applies to nonprofits. Basically, it says, ‘Thou shalt have transparency. Thou shalt have no conflict of interest.’ ”

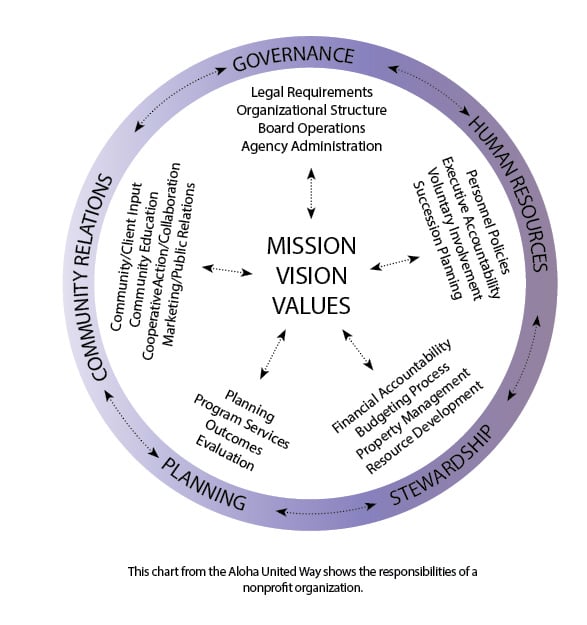

That gets to the heart of a board’s function. Few board responsibilities seem as obvious as those that generally fall under the heading, governance. Executive directors say (some of them reluctantly) that these includes basic functions: assuring that the organization complies with legal requirements, like making its IRS filings on time; making sure there are adequate policies to prevent issues like self-dealing and conflicts of interest; and recognizing that the board is the organization’s primary vehicle for public relations. These responsibilities aren’t all that different from those that for-profit boards assume.

When you talk to executive directors, especially those that have been successful, they almost uniformly say that nonprofits and their boards need to be more “businesslike.” For the board, that means making sure your executive director and staff perform their duties as professionally as possible given their resources. It also means being accountable for your own responsibilities, which ultimately are the health and welfare of the whole organization. Because the board of directors isn’t simply an advisory body added as an afterthought. The board is the legal embodiment of the organization.

It’s a concept that flies in the face of the egalitarian ethics of most nonprofits. “You want it to be all cordial relationships,” Holly Henderson says. “You want everyone to be equal. But in the end, you can’t get around the fact that the board is the boss.”

Now, if they’d just act like one.