More Efficient Power

In the hospitality world, it’s not just hotel guests who win points and rewards.

The Westin Princeville Ocean Resort Villas on Kauai’s North Shore earned a bonus when it installed a system that delivers electricity more efficiently and comes with a free byproduct, heat.

That byproduct, which would normally be wasted, is harvested to run the Westin Princeville’s absorption chiller for its air conditioning, to warm the hotel pool and spas, provide hot water, and light tiki torches after dark.

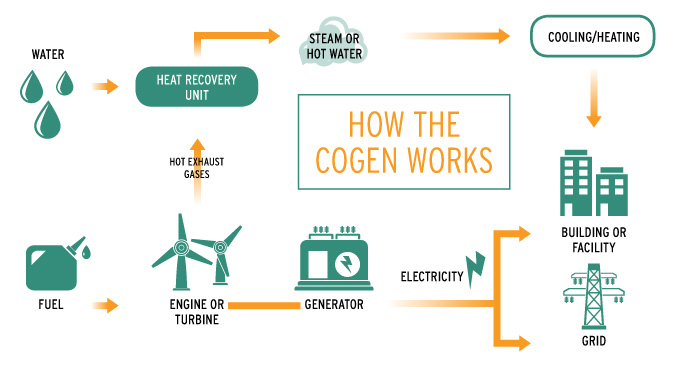

Known as “cogen,” for cogeneration, the resort’s recently completed Combined Cooling, Heat and Power (CHP) plant runs on propane, often referred to as liquefied petroleum gas. Propane is produced from both natural-gas processing and crude-oil refining.

“From an economic standpoint, it was the most feasible option to reduce energy costs, consumption and carbon outputs versus other commercially available distributed power- generation systems,” says Brian Harrier, the resort’s director of engineering.

“LPG is a very clean-burning fuel source, so our exhaust output is much more environmentally friendly than a typical diesel or gasoline-fueled system,” he says. With a peak output of 1 megawatt, the CHP system provides nearly enough electricity for the resort’s peak load, though the load is usually lower.

“(Because) we are able to utilize the heat energy that would otherwise be discharged out of a conventional system, our overall system efficiency is approximately 70 percent versus a typical utility maximum efficiency of 35 percent,” Harrier says. Part of what makes CHP so efficient is the onsite distribution, which eliminates electricity losses from transmission, but might prove a drawback aesthetically.

THE WESTIN’S EFFICIENCY IS 70% VS. A TYPICAL UTILITY EFFICIENCY OF 35%.

“The noise levels of our system are low,” Harrier says. “We were able to obscure our system visually so as not to detract from the Westin Princeville’s beautiful grounds. And, our infrastructure has improved vastly, as we now have redundancy built into all of our major electrical and mechanical systems,” he says.

The hotel remains connected to the Kauai grid, Harrier says. “In the event of an equipment outage, we are able to seamlessly transition between power sources. The system does allow us an additional barrier against loss of grid power, and does contain the capability of running in standalone mode.”

Hawaii hotels that have turned to CHP for their energy include the Kauai Marriott Resort & Beach Club in Lihue, which also uses propane, and the Four Seasons Resort Hawaii, Lanai at Manele Bay, which runs on diesel.

“CHP works best when there is a steady thermal (A/C or heat) load,” says Joe Boivin, senior VP for business development and corporate affairs at HawaiiGas. “Particularly hotels and hospitals that need steady air conditioning and hot water. It also works when these loads vary, but the economic returns may not be as high, so each application must be assessed on the specific economic benefits.”

Boivin says several CHP projects are currently in the planning stage.

Back to the future

Though the Westin Princeville’s plant is at the cutting edge of engineering and design, CHP is a well-established technology.

Favored mostly on college campuses, in hospitals and for industry, CHP has been around in the U.S. since Thomas Edison used it to power the world’s first commercial power plant in Manhattan. As technology advanced to large, centralized generators, CHP declined in favor of easier-to purchase electricity.

But, in 2013, rising energy needs and renewed interest led the U.S. Energy Department to announce $11 million in funding for centers that help local businesses develop CHP projects. The Energy Department estimates the nation has an installed capacity of more than 82 gigawatts of CHP – equal to 8 percent of total generating capacity.

Clean, but not renewable

How does CHP fit into the state’s energy future? One disadvantage is that it makes no use of renewable sources such as wind and solar power, says Richard Wallsgrove, program director at the Blue Planet Foundation. He was not familiar with the Weston Princeville CHP system, but says, “While more distributed generation can be a good step forward in Hawaii’s transition to 100 percent renewable energy, CHP that burns propane is not a great idea. It is not renewable. It is not local.”

He says the foundation would be especially disappointed if a CHP project took a business off the grid and made it completely dependent on fossil fuels, at the same time that energy on the grid is increasingly coming from renewable sources. “That type of CHP would actively slow down the state’s transition to 100 percent clean, local energy,” he says.

Law professor Shalanda Baker, who teaches renewable energy, policy and climate change at UH’s Richardson Law School, advocates a balance.

“Hawaii has the capacity to enter a 100 percent renewable-energy future. But any time you are able to generate electricity in a way that is more distributed, whether by clean or more traditional fossil-fuel mechanisms, the argument is you are bringing more resilience to the grid,” she says.

“Propane is clean, but as we investigate ways to bring about creative distributed energy, let’s make sure we use the resources readily available on the table – wind, solar, wave power,” Baker says.

Photo: Thinkstock