Matson Sails Fast Boats to China

Matson Navigation Co. is a tiny blip on the radar compared to the 20 other major global transportation companies serving the China market. Still, as the first American shipper to enter the China trade, it’s secured an impressive client base by providing what it and others say is the fastest, most reliable, on-time service from China to Long Beach.

Matson Navigation Co. is a tiny blip on the radar compared to the 20 other major global transportation companies serving the China market. Still, as the first American shipper to enter the China trade, it’s secured an impressive client base by providing what it and others say is the fastest, most reliable, on-time service from China to Long Beach.

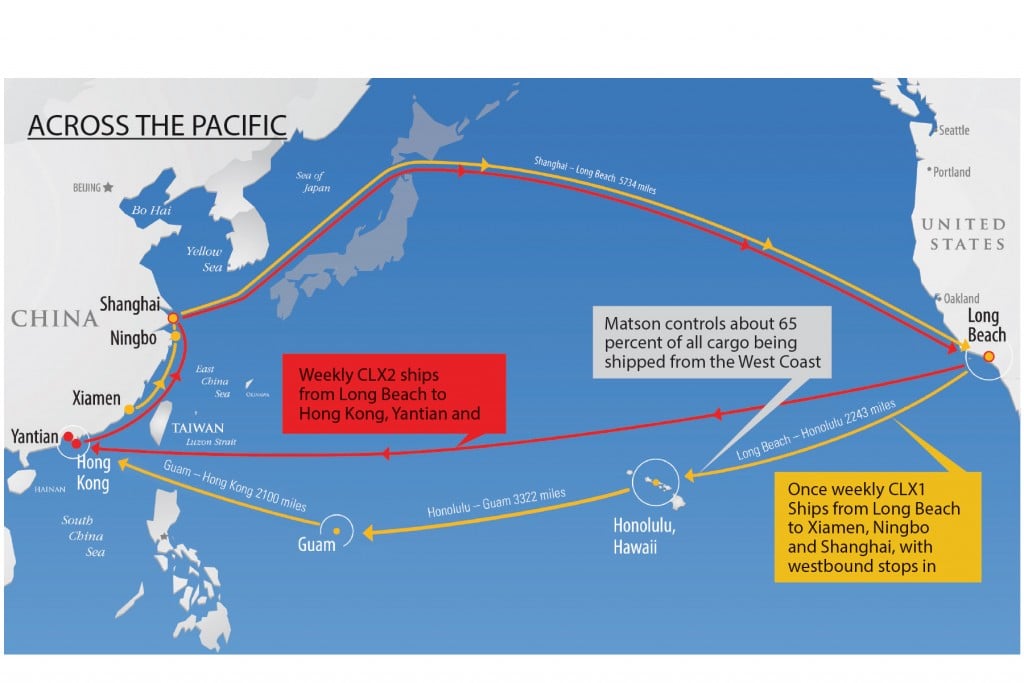

On the fifth anniversary of its China to Long Beach Express (CLX1), Matson president Matthew Cox says the company is profitable and anticipates its CLX2 route will double its Asia capacity. Matson’s parent, Alexander and Baldwin Inc., reported net income of $25.7 million for the third quarter of 2010, compared to $8.5 million for the same period in 2009, and much of that is due to its China route.

That success hasn’t gone unnoticed. Horizon Lines, Matson’s biggest competitor in the West-Coast-to-Hawaii market, recently launched its own China-to-Long-Beach service. Still, the most important story to be told isn’t about who will capture the most customers, it’s that A&B proved a Hawaii company can compete – and turn heads – in a global economy.

New kid on the block

Matson executives knew if they wanted to grow the company, they’d have to look outside Hawaii. But expansion came with tremendous risk: There were already many carriers serving China, each with more experience, loyal customers and bigger ships.

Even though Matson had been serving the Pacific since 1882 and moves about 65 percent of all cargo from the West Coast to Hawaii, it didn’t know how its five-vessel fleet would be received at foreign ports. The biggest unknown, says Stanley Kuriyama, president and CEO of A&B, was whether Matson would be able to break into a new market, secure customers and compete against the world’s mega-carriers.

Matson went for it anyway, investing $365 million on new vessels, containers and a dedicated terminal in Long Beach.

“When we placed the original order for the ships, we knew they were going to be delivered in about a year,” Cox says. “So we had one year to plan, present and hire the right people, and work on the hundreds of elements that were required to start this new service.”

Although Kuriyama was not head of A&B when CLX1 was launched (he led the company’s real estate division), he knows it was a huge undertaking with much pressure to succeed. But even if the China route hadn’t been a home run, A&B “still would have been OK,” he says. “We just would have been that much less profitable. With that said, the income from the China route has been crucial, especially considering how tough the economy has been over the past couple of years.”

Head of the class

Before launching the CLX1 route, Matson had partnered for 10 years with an international company, American President Lines, serving Guam. When that alliance ended, Matson wanted to continue the service but needed a way to make the route work financially. For years, Matson’s and Horizon’s ships had sailed full from the West Coast to Honolulu and Guam, but returned to the West Coast almost empty. The new route lets Matson make a continuous loop with a full load on almost every leg, which improves the company’s operating costs. Ships now fill up in China, unload and reload in Long Beach, and then sail to Hawaii and Guam, unload again, and return to China. The ships are only empty on the relatively short Guam-to-China run.

“We’re basically full in both directions,” Cox says. “To my knowledge, we are the only ones sailing back (westbound) full on our Jones Act service.”

When it launched its CLX1 service with five ships, Matson had one of the smallest fleets and handled about 2 percent of total shipments from China to the U.S.

“There was a theory on how we could compete,” Kuriyama explains. “We knew we couldn’t just go head-to-head with the big guys because they had their established customer base and mega-ships, so we had to figure out a new way of competing.”

That they did.

Smaller ships mean Matson can make Shanghai, a shallow-water port, its last port of call. Larger ships cannot top-up in Shanghai and, therefore, must make another stop at a deeper-water port. This allows Matson to offer the fastest transit time, 10 days, from Shanghai to Long Beach.

“The next closest competitor when we launched was 12 days, so we had a two-day service advantage,” Cox says. “It’s actually expanded from that now. What’s happened in the meantime is that many of the international steamship lines have actually slowed their ships down – they call it slow steaming – in order to try to save fuel.”

Another measure of Matson’s superior service is the quick availability of its cargo upon arrival in Long Beach. Smaller vessels allow 100 percent of cargo to be unloaded within 24 hours and then transferred to Matson’s exclusive off-dock facility, where customers can pick it up and avoid long lines at the congested port.

“As an example, Matson’s ship arrives Sunday morning in Long Beach at 6:30,” Cox explains. “We’re able to discharge the 1,000 loads that we have on the ship and move them all on Sunday night to an off-dock facility a few miles away from the port so that Monday morning at 5:00, all 1,000 containers are available for pickup. If you operate a very large ship, it might take you up to 2.5 days to discharge the last part of the cargo and then you face as much as a four-hour delay waiting to get into the gate at the very crowded international marine terminal. So, we have 10-day transit, 11-day availability. The availability of some of our other competitors is probably 14 days after slow-steaming, so we’re somewhere between three and seven days faster than most of the market.”

Matson’s efficiency has attracted a niche of clients who ship higher-ticket, time-sensitive items but want to avoid costly air freight.

Cox says the international on-time standard for arrivals is about 60 percent. In 2007, a survey by Drewry Shipping Consultants, an independent global maritime consulting and publishing company, ranked Matson the No. 1 on-time carrier in the world, and Matson says it continues to lead the industry with reliable service.

Ninety percent of the cargo shipped from China to Long Beach remains on the Mainland, where Matson serves more than 300 customers. Art Wong, assistant director of communications for the Port of Long Beach, says Matson has a reputation for good service. “They offer a big advantage for customers who want to get their products landed and delivered quickly,” he says.

Dennis Teranishi, president and CEO of Hawaiian Host, says Matson has shipped its products from the West Coast to Hawaii for decades. “If Matson’s service in China is anything like the service they provide for our shipments, I know their customers are happy,” he says. “We’ve found the agents to be very responsive and customer-service oriented.”

Five-year overnight success

Even though Matson had a ton of experience serving the Pacific market, success in China didn’t come without growing pains.

“If you’re a new carrier, you have to prove yourself,” Kuriyama says. “(Customers) want to know that you’re reliable and efficient in the way that you handle their goods. We definitely had to work to keep their business.”

Kuriyama says that, even though the CLX1 service was embraced from the beginning, Matson was under the microscope until it demonstrated that it could deliver on its promises.

In 2009, Matson was tested when the global recession depressed demand for containerized cargo as retailers and consumers reduced their spending. Like many other companies, Matson reacted by cutting costs and reducing staff.

During the strong economy in 2006 and 2007, Kuriyama says, many shipping companies ordered new vessels, thinking business would keep rising.

“So now there’s this huge influx of shipping capacity and lower demand and the cost of fuel was at an all-time high. It was just a bad time for the shipping industry,” he says.

But Matson has fared well compared to other shipping companies and it’s seen a nice recovery in freight rates in China in 2010 as the world economy slowly recovers, Cox says. “We’ve held our own in a pretty tough market.”

China is the world’s fastest growing major economy, so it’s a big opportunity for a Hawaii company. In 2009, Matson shipped about 47,000 containers from China to the West Coast – which represented about 25 percent of its container business.

“To do business in China, you have to understand their culture, their way of doing business, their laws,” Kuriyama says. “Whenever you venture outside of your own market, it’s all about who you know, what you know and having a true understanding, not a superficial one, of how the markets work there. And I think we’ve done pretty well.”

Full steam ahead

Since 2008, A&B’s three main business lines – agriculture, shipping and real estate – have felt the pain of high oil prices, lower demand for retail products and the real-estate slowdown. In 2009, A&B posted a record $30 million loss for its agricultural businesses as a result of a devastating drought on Maui; 2007 and 2008 were the driest back-to-back years in A&B’s history, Kuriyama says, which impacted 2009 revenue.

Net income for the first three quarters of 2009 was $24.1 million. That figure spiked to $71.9 million for the same period in 2010.

“There’s no question, Matson’s CLX1 has been instrumental in A&B’s recovery in 2010 over 2009,” Kuriyama says. “When you compare the two year’s (shipping) performances, you basically see flat, stable volumes in Hawaii and in Guam, but we saw a significant increase in rates and volume from China.”

In 2009, A&B’s operating profit for its ocean transportation division in the third quarter was $24.2 million. The same quarter the following year, it jumped to $40.4 million – a 67 percent increase – and Kuriyama has but one explanation: “China.” He says the company is in a strong financial position with a solid balance sheet and available lines of credit, which will allow for future growth.

“Our stock has been doing pretty well more recently but we did take a big plunge early in (2010),” Kuriyama says. “The market was in turmoil and there was a huge uncertainty in all lines of business, but as our performance improved over the year, so did our stock-price performance.”

Cris Borden, partner and chief investment officer for Kobo Wealth Conservancy, says he’s somewhat surprised that A&B’s stock wasn’t hit harder because of the nature of its business lines – sectors that all saw steep declines. In 2008, Borden says, the shipping industry was down 56 percent while A&B was down 49 percent, “so they did better than the overall shipping industry,” he says. “For A&B, their shipping is so critical to the security of Hawaii, which is probably why it did a little better than other shippers around the world.”

Borden says A&B’s China strategy and presence has probably helped its stock price. “They have a young shipping fleet, which apparently gives them better operating margins, so I think that’s helped them as well.

“A&B is representative of the overall Hawaii economy, so their stock price is probably a good indication of where Hawaii is heading, in terms of the economy.”

Globally, Borden says there are about 70 other publicly traded shipping companies. “It’s difficult to say how Matson measures up to the competition because A&B’s market capitalization includes all of its subsidiaries,” he explains. But, he says, investors are confident that A&B will continue to be profitable in 2011.

“According to industry experts, shipping rates should remain depressed over the near term, but A&B’s service out of China should mitigate their downside risk. … A&B is older, they’re well established, they have good cash flow and they’re a mature company, so you normally don’t see major volatility in stocks like that.”

Continued growth

Matson expects its CLX2 service to double its China capacity. The route is a direct loop between Long Beach and Southern China, without stops in Hawaii or Guam. The challenge now is to find more paid cargo to be shipped from the West Coast to China.

In December, Horizon Lines kicked off its own service from China to Long Beach, called Five Star Express, which offers an 11-day transit time. Both Horizon and Matson hope to accommodate an expanding military presence in Guam.

“We certainly feel in some way flattered that (Horizon Lines) is going to try to copy the trail that Matson’s blazed and we wish them well,” Cox says. “By the other token, they’re just one of 20 competitors in the China trade. We aren’t overly worried about them and we’re going to continue to focus on what we’ve built on in the last five years.”

The Port of Long Beach’s Art Wong says China is the manufacturing center of the world and the largest market for containerized shipments, so there’s plenty in China to keep all of the major international shippers busy.

“It could get interesting but it’ll all come down to who can provide the best service,” he says. “And, right now, there are definite advantages to shipping with Matson.”

Kuriyama says A&B is poised for recovery as Hawaii’s economy strengthens and the company will continue to look at new ways and places to grow within its core businesses.

“For us, this is a long-term story that we’re trying to tell. And even though we’re expanding to China and that route has been successful, it’s important to remember that we’re still a Hawaii company, so no matter where we do business, this will always be our focus. Hawaii will always be our home.”

MATSON’S SHIPS

CLX1 vessels (the Hawaii ships): Each can carry about 1,000, 40-foot containers.

CLX2 vessels: Each can carry about 1,500 containers.

Typical cargo: Higher-value goods, such as electronics, fashion garments for major retailers, and high-end furniture.

Volume in 2009:

Hawaii-bound containers: 136,100

Hawaii-bound automobiles: 83,400

Guam-bound containers: 14,100

China-to-West-Coast containers: 46,600

Volume in 2008:

Hawaii-bound containers: 152,700

Hawaii-bound automobiles: 86,300

Guam-bound containers: 13,900

China-to-West-Coast containers: 47,800

Matson’s CLX1/Hawaii fleet:

MV Maunalei

MV Manulani (at right)

MV Maunawili

MV Manukai

MV R.J. Pfeiffer