Many Remain Unemployed Despite Lots of Job Openings

On a typical day, there are more than 2,000 Oahu job listings on Craigslist. So why are there tens of thousands of people in Hawaii who want to work but donʻt even have a part-time job? Hereʻs why and what we can do to help them get back to work.

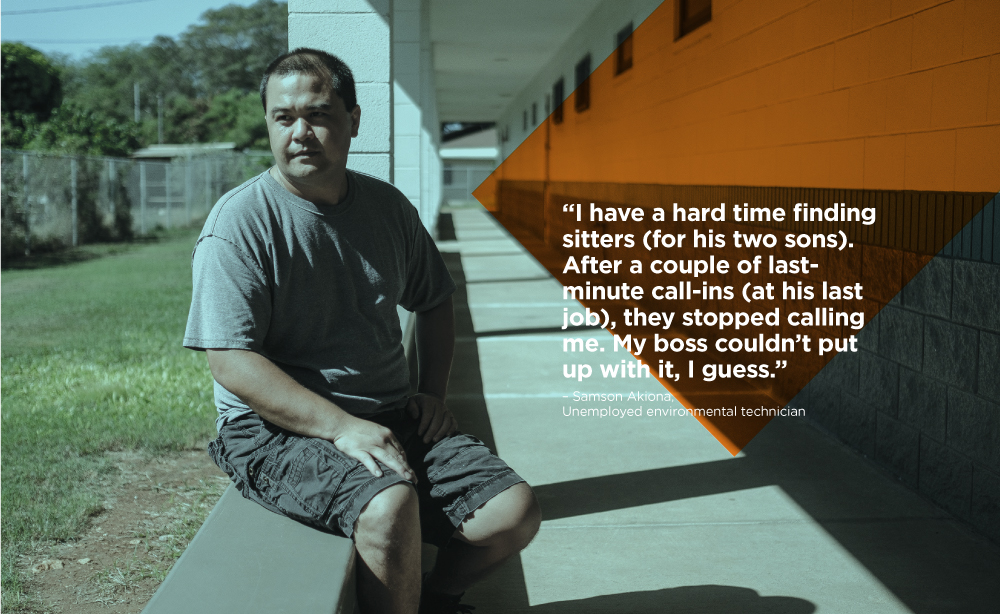

Samson Akiona is a 36-year-old single father living in Waianae, raising two young children, and doing it without a paying job. Instead, he and his family survive each month on a $400 welfare payment, $600 in food stamps, now called SNAP benefits, and a Social Security disability check of $600 for one of his sons.

Akiona has been out of work since January, though he does 30 hours a week of community service at the Honolulu Community Action Program’s office in Waianae, trying to work off thousands of dollars in driving fines and get his life back on track.

After high school, and with assistance from an Alu Like intern program, he trained as an environmental technician in conjunction with California’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories, then worked for several years on the Kahoolawe clean-up. Later he earned a certificate as a medical assistant from the Hawaii Technology Institute. But many jobs he’s taken in recent years don’t use those skills.

“This is the longest I’ve been out of work,” says Akiona. “It’s harder for me because I’m older, and they’re looking for the younger guys. I think I’ll have to work twice as hard to get the job. Even now it takes me months to find a job. When I was younger it was just a couple of weeks.”

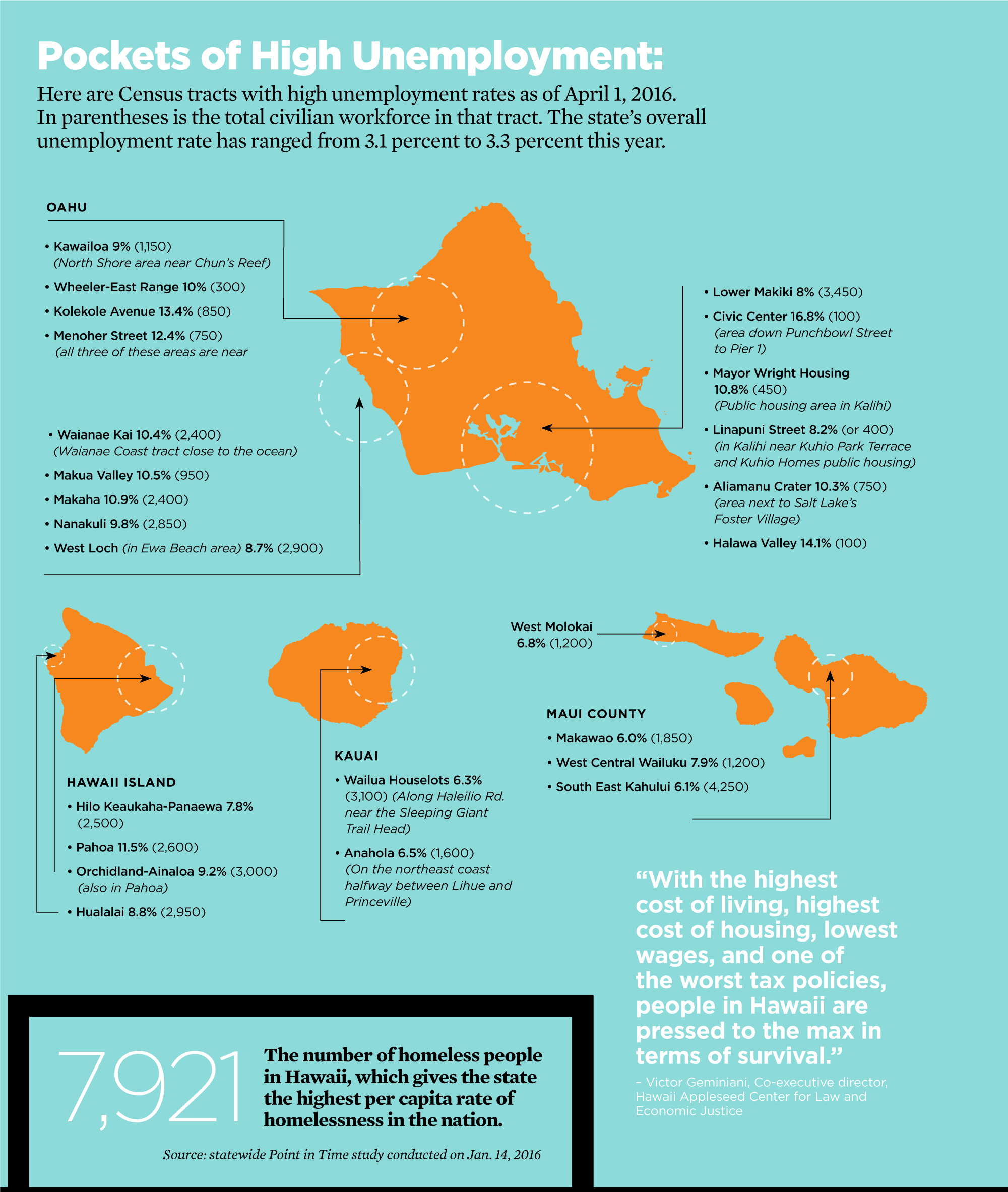

Hawaii’s overall unemployment rate has hovered around 3.2 percent all year, but the unemployment rate is 10.4 percent in the Waianae Kai neighborhood where Akiona and 2,400 other civilian workers live. It is one of the highest unemployment rates for census tracts in Hawaii, according to the state Department of Labor and Industrial Relations’ Research and Statistics Office.

In two dozen census tracts of high poverty scattered around the state, the unemployment rate is double or triple the state average, or worse. On Oahu, at Mayor Wright Housing, it is 10.8 percent; Makua Valley 10.5 percent; and among Halawa Valley’s 100-person workforce, the rate is 14.1 percent. The highest Neighbor Island rate is in Pahoa on Hawaii Island, 11.5 percent. And these rates do not include the tens of thousands of people in the prime working age, 25 to 54, who have given up looking for work.

Of course, a neighborhood with a 10 percent unemployment rate has a 90 percent employment rate. The vast majority of people who want work, have a job.

So why do the 10 percent fail to have jobs?

• They may lack the skills, education and experience demanded by employers, or the so-called soft skills such as reliability and punctuality, and the ability to work with other employees and customers.

• They may face additional challenges such as mental illness, substance abuse, criminal records or suspended driver’s licenses.

• Many families, but especially single parents not living within an extended family, have difficulty finding affordable and dependable child care.

• Available jobs may be far off, or job seekers can’t afford a car to get there or it can take hours by bus each way.

In some cases, families face none of these challenges, but are living so close to the edge financially because of low wages that losing a job can lead to eviction and homelessness, which makes it harder to find and keep another job.

The social breakdown feeds a cycle in these families and neighborhoods, of reduced opportunities for children and young people, and a dependence on public assistance from the state and counties.

Akiona’s personal situation is somewhat typical in that it’s based on many factors and defies an easy solution. He says child care is a recurring challenge plus he lost his driver’s license a decade ago and owes $13,000 in fines from driving illegally. His volunteer work is part of a commitment he made to the court to get his life together, including clearing his record so he’s eligible to regain a driver’s license.

“Most jobs ask for licenses,” he says. “Even for laborers they ask for licenses.”

Denise Konan, an economics professor and the dean of the College of Social Sciences at UH Manoa, says these problems create a downward spiral.

Denise Konan and Nori Tarui, an associate professor of economics, in her UH office. Photo: Aaron K. Yoshino

“A lack of employment tends to lead to declines in those communities and a lack of investment,” she says. “And there’s a greater need for social services – not just for those unemployed, but for their families. It’s a cost to society as a whole because we’re not tapping into the human capital of those people.”

“They’re not contributing in a productive way to the economy, and they’re also not consumers, and that creates lack of demand in an economy.”

The potential problems are myriad. “If there’s a loss of health insurance and health care, some basic health needs may not be met,” said Konan. “You could have treatable illnesses turn into chronic conditions.” That makes it even harder to find and keep a job.

“As well, there is a ‘discouraged worker’ impact that unemployment statistics don’t capture. If you’re seeking work (and don’t find it), there’s a point at which you become discouraged … We know from social research this can be associated with mental health and physical health problems. The stress it causes families, and elevated states of depression, have been well documented. And that can carry over into an impact on children that can be perpetual, and cross generations.”

Over the past three years, Akiona has held three jobs, one for two years, another for six months and a third for three months. Often, he had to call in sick due to lack of child care or because of a sick child. That’s why he lost his last job doing fire watch at Pearl Harbor.

“I have a hard time finding sitters,” he says. “After a couple of last minute call-ins, they stopped calling me. My boss couldn’t put up with it, I guess.”

So the key to getting most of Hawaii’s unemployed people back to work long term is breaking their downward spiral – where one problem leads to another and then two more and eventually you are in a hole that’s hard to climb out of. Of course, breaking that downward spiral is a huge challenge. Housing is an enormous factor.

Nathan Alfaro is a housing specialist with Catholic Charities who works with many people who have lost their jobs and, therefore, are in danger of being evicted from their homes. Often, he says, the downward spiral begins with a lost job, and then transportation and child care become major barriers to finding another. Often struggling families don’t have internet access and that also impedes job searches.

“There’s a chain of events,” says Alfaro. “What I see is short-term employment, with most clients on a job less than two years, or even less than that – maybe even just six months. There’s a lot of turnover. And, honestly, there are multiple facets to that, such as children coming into the house, and heavy debt. I see clients playing catchup to traffic infractions, bench warrants, suspended licenses; some who have been incarcerated find employment after that is difficult.”

One problem, like a suspended license, can create a circle of problems that’s hard to escape, says Alfaro. “If you can’t drive, you can’t go to work. And if you can’t work, you can’t pay the debt. There’s a bus system and agencies that assist with bus passes,” he says, “but it’s definitely a Band-aid on a bigger wound.”

The all too common consequence is homelessness. John “Jack” Barile, assistant professor of psychology at UH Manoa, says his research shows that losing a job is the No. 1 cause of homelessness. Many Hawaii residents are paying a huge part of their wages on housing – barely able to make their rent every month – and all it takes is missing a couple of paychecks and they are homeless.

“The cities with the highest rents traditionally have the highest homelessness,” Barile says. “And if you have a very small inventory of housing, there’s the biggest squeeze on the lowest cost rentals. Once you become homeless, it’s hard to look presentable at job interviews, or have a reliable mailing address. And, if you’re newly homeless, you don’t necessarily know where all the resources are.”

Barile says that, from his perspective, some of the best and most promising programs aim to break the cycle by keeping people in their homes, or putting them back into housing soon after they end up on the streets. These programs are “aimed at identifying and working with families and individuals who are at risk of becoming homeless or recently homeless. The major thing they need is financial support – either to get back into housing, or maintain the housing they’re at risk of losing.”

Another challenge is getting part-time workers into full-time, secure jobs and getting the long-term unemployed back to work. Many of the long-term unemployed don’t count toward the official jobless rate because they have given up actively looking for work, even though they want to work.

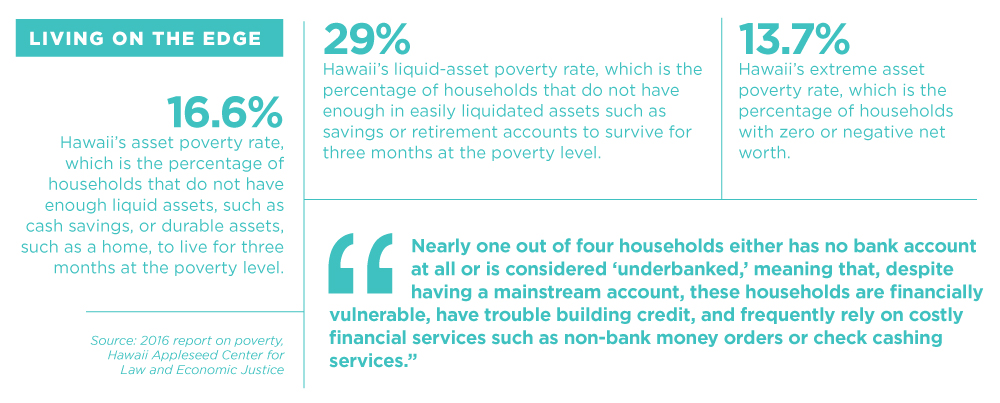

A 2016 report on poverty by the Hawaii Appleseed Center for Law and Economic Justice offers startling statistics on the phenomenon.

“The low official unemployment rate (of 3.1 percent) obscures the reality for many of Hawaii’s families; those who want a full-time job but can only find part-time work. Using the fuller metric of ‘real’ unemployment, close to one out of 10 people (9.7 %) who would like to work full time in Hawaii are either unemployed, underemployed or have not looked for a job during the past month,” says the report, written primarily by Nicole Woo, a senior policy analyst at Appleseed.

Professor Sang-Hyop Lee, a labor analyst in the Department of Economics at UH Manoa, says service jobs, like those in tourism, Hawaii’s largest industry, are often part time and susceptible to layoffs. When workers can’t find another job after four to six months, they can become discouraged, says Lee, and stop actively looking for work.

The Appleseed report provides a broader vision on how to break the downward cycle: get more money into the hands of poor people, because they usually live so close to the financial edge that the smallest problem can lead to a crisis.

More money also can break the generational cycle of children raised in poverty spending their whole lives in poverty.

“As poverty rates in a neighborhood increase above 20 percent, children’s opportunities for success are diminished,” the report notes. “Decades of research have shown that economically disadvantaged students perform less well in school, regardless of the quality of their education. More than 40 percent of the variation in average reading scores and nearly half in math scores is correlated with variations in child poverty rates. This achievement gap continues to widen as income inequality increases.”

The report concludes that helping families attain and maintain employment calls for policies that help workers care for their families. These include:

• Increasing opportunities for child-care subsidies.

• Early childhood education.

• Before-school and after-school programs.

• Paid family and medical leave.

• Long-term care.

• Programs to encourage asset building.

• Tax fairness measures including a low-income household renters credit.

• Eliminating income taxes on people in poverty.

• Creating a state-earned income tax credit to supplement the federal EITC, which is a refundable federal tax credit aimed at working families with especially low incomes. The report says this encourages work by allowing families to keep more of what they earn.

Waianae, where Akiona lives, has always faced employment challenges. The neighborhoods along Oahu’s west coast are far from the island’s job centers; the growing city of Kapolei has provided more options in recent decades, but most of its workers live there or a little to the east.

Other rural areas face similar challenges: for instance, Pahoa on the Big Island with 11.5 percent unemployment.

Akiona is involved in two government programs that aim to put people back to work by overcoming personal challenges or legal roadblocks: Welfare to Work and Na Lima Hana. WtW is operated by HUD, the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development, and Na Lima Hana is run by the Hawaii Community Action Program. Together, they aim to train people to become economically independent, and provide assistance with child care, housing and other social services.

Hawaii Community Action Program also helps place people in community service positions that will help them regain employment.

“To get my license back I’ve got to do all this community service,” says Akiona, who has also joined a church and says his new spiritual beliefs are helping him remain focused. “I’m almost finished up at this section (of community service) and then I’ll go back to court and see what else the judge has.”

Throughout the summer he’ll continue to rise at 4 a.m. to make food for his sons, and get them ready for Summer Fun, before a bus takes the two boys to the playground and Akiona to the HCAP office where he volunteers for 30 hours a week.

Computer access at HCAP means he can look for potential jobs while he’s volunteering, although he’s hoping to become a teachers’ aide at his children’s school.

“If I finish this section, Waianae Elementary might give me employment,” he says. “The kind of job that would make me happiest is one closer to my sons’ school. … I just have to go through the steps to get to where I want to go.”

Going through steps imposed by a court is often one piece of the complex picture of unemployment. Housing is another piece, and when a housing issue ends up in court, the tenants almost always lose and get evicted, because they rarely have a lawyer, says Victor Geminiani, co-executive director of the Hawaii Appleseed Center.“We did a study in 2010 of 205 eviction cases in District Court on Oahu, and here are the startling figures: We saw that 70 percent of the landlords were represented by attorneys, while only 4 percent of tenants were. In 97 percent of the cases, the possession went to the landlord. In 50 percent of the cases, the tenants didn’t even show up in court.”

Geminiani said the trials lasted an average of 75 seconds, with an overwhelming 90 percent of the people being evicted, “which meant they could be evicted after two or three days, with no grace period.”

There are numerous possible defenses for tenants, said Geminiani, but without legal assistance, they are at a disadvantage. “Unless you know the law, and can defend yourself, it’s very hard to do that.”

A study funded by the University of Zurich, and published in The Lancet in 2015, found that 20 percent of suicides in 63 countries were linked to unemployment. Using data from the World Health Organization, analysts looked at a total of 233,000 suicides annually between 2000 and 2011. They discovered that around 45,000 suicides – about one in every five – were linked to unemployment. However, other researchers have also looked at this issue and found there may be no simple relationship between unemployment and suicide; rather, losing one’s job may be one of many stressors, including mental illness, that lead to suicide.

The Appleseed report says that even a reliable full-time job is not always the answer, if the job pays low wages. The minimum wage in Hawaii rose to $8.50 on Jan. 1, 2016, will rise to $9 on Jan. 1, 2017, and to $10.10 on the same date in 2018.

Hawaii’s residents earn the lowest wages in the country when adjusted for the cost of living, says the Appleseed report. A parent with a single child who works 40 hours a week at minimum wage would still live below the poverty level.

“People living at or near poverty are spending more than 50 percent of their incomes for housing, which leaves virtually nothing left for food, clothing, insurance, car repairs and everything else,” Geminiani says. “People in Hawaii are pressed to the max in terms of survival.”