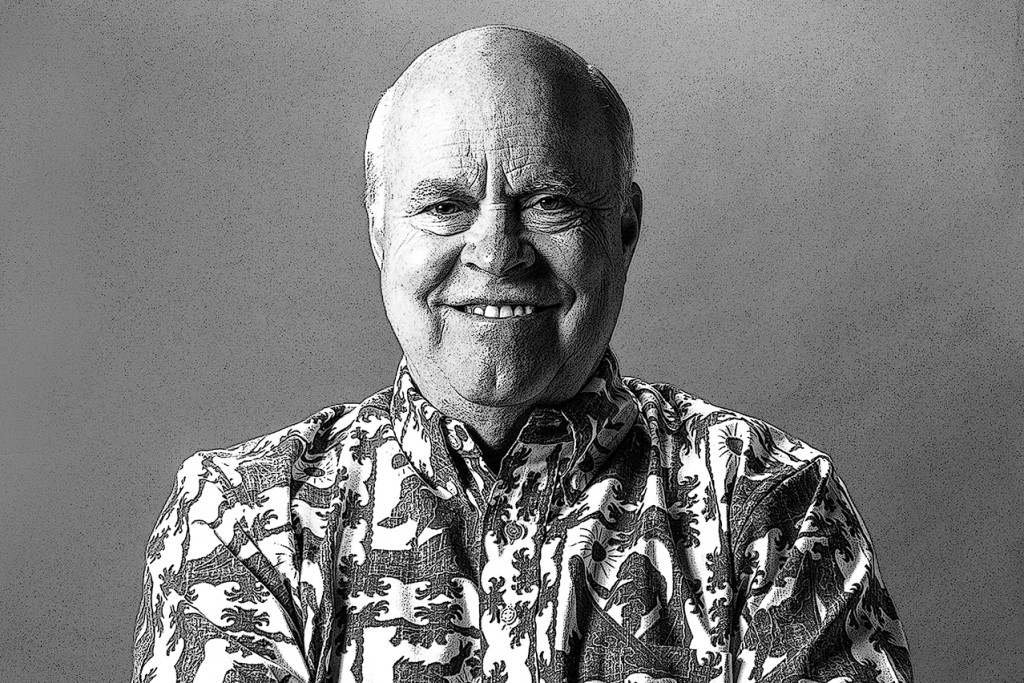

Man at the Center

YES! A Memoir of Modern Hawaii

By Walter Dods Jr., with Gerry Keir and Jerry Burris

Walter Dods Jr. was born in Honolulu just before Pearl Harbor, the first of seven children in a close-knit family that struggled to pay its bills. From those modest beginnings, Dods grew to play a major role in the modern history of Hawaii. He helped to sustain a political dynasty through his work for the campaigns of Gov. George Ariyoshi and Sen. Dan Inouye. At one time, he was under pressure to run for governor himself. He built the state’s oldest bank into its biggest bank, First Hawaiian Bank/BancWest Corp. His focus on community service and charitable fundraising has helped to support a society too often fractured by the divide between an immigrant, plantation past and the modern forces of contemporary America. His memoir describes many of the steps – and occasional missteps – along the way and concludes with his observations on the nature of power and ways in which the Islands’ young people can find success while staying true to “local values.”

Watermark Publishing / sales@bookshawaii.net

© 2015 Walter A. Dods Jr. (All of Dods’ proceeds from the book are being donated to the Aloha United Way.)

The Letter

An inside story of Sen. Dan Inouye’s famous letter delivered to Gov. Neil Abercrombie about his preferred successor

By Walter Dods Jr.

Several months before Sen. Dan Inouye died of respiratory complications, I happened to be one of the first to know that his deteriorating health was more serious than most people suspected. He was in town and called to ask me to have lunch with him at the Bankers Club upstairs from my office at the First Hawaiian Bank tower. He said, “I have an appointment with the doctors at Tripler and may be a little late, but I’ll come right afterwards.”

When he arrived, he said, “I just came from Tripler and I now realize that these doctors at Walter Reed pretty much have been blowing smoke up my ass.” (Walter Reed is the national military hospital near Washington, D.C.)

“They tell me, ‘You’re great, you’re feeling good, your heart beat is so great and all the rest of it.’ This is the first time I ran across a doctor at Tripler, and he told me that I have serious problems with my breathing.”

He said he was going to have to start going around with oxygen more. Then Dan told me: “It’s clear now that I’m not going to be around forever and I want to do everything I can to position Colleen (Hanabusa) because …” (This is the part people don’t understand, people are going to say it’s the old guys trying to keep in power, but what Dan said to me was: “I’ve had the chance to look at all the people involved, and Colleen clearly is the one who should be there.”) Meaning there in the Senate to succeed him. He said, “Please let me know anything that I can do, anything that would be helpful to Colleen.”

“When Inouye arrived, he said, ‘I just came from Tripler and I now realize that these doctors at Walter Reed pretty much have been blowing smoke up my ass.’ ”

He was almost 88 years old and until that day had always talked about the next election. The last time he ran, in 2010, after it was over we were all tired, but the next day at breakfast, it was, “I’m going to run again in six years.” That day at lunch was the first time I knew he wasn’t thinking that way. This was the first time he indicated, “I’m not going to be there, and we need to make sure Colleen is ready.”

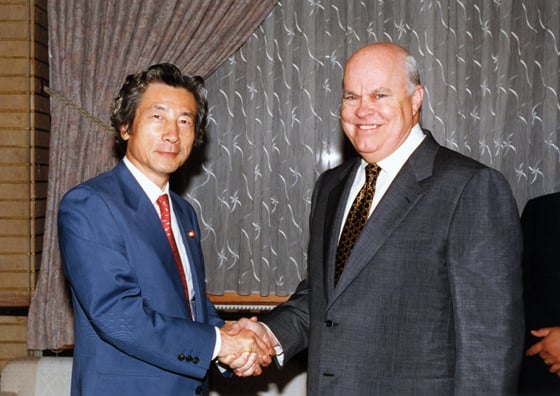

An early meeting of the Japan-Hawaii Economic Council, which played a major role promoting business between Hawaii and Japan starting in the 1970s. Gov. George Ariyoshi sits between John Bellinger (arms crossed) and Walter Dods, who served successively as CEOs of First Hawaiian Bank. Below, Dods with Sen. Daniel Inouye. Photo: Courtesy of Walter Dods Jr,

After that, I was told by his staff and his second wife, Irene Hirano Inouye, that he was starting to get on oxygen pretty heavily. He wouldn’t use it when he walked out to the Senate floor or at public hearings. Even in Honolulu, the Secret Service bodyguards who were always with him (as Senate president pro tem, he was third in line to the presidency after the vice president and the speaker of the House) found ways to drive him almost to the door of wherever he had to be. For instance, at the Hilton Hawaiian Village, you can take that ramp all the way up, almost to the entrance of the Coral Ballroom. Then he would be without oxygen for a short period of time in public, but he was on it much more than people thought: In the car, at home, even in the office, quietly.

When he went into Walter Reed nine days before he died, it became more widely known that he was using oxygen and, sometimes, a wheelchair. His staff attributed the need for oxygen to being misdiagnosed with lung cancer in the late 1960s and having part of a lung removed.

Just hours before hearing of his death, my friend Jeff Watanabe and I had delivered a letter to Gov. Neil Abercrombie on the senator’s behalf. It contained, to no one’s surprise, Inouye’s wish that Abercrombie appoint then-U.S. Rep. Colleen Hanabusa as his replacement. There have been stories that the letter was fabricated by Inouye’s staff after he was no longer able to function, but I don’t buy that. After all, it was already well known that Inouye wanted Hanabusa to succeed him.

I remember that meeting vividly. Jeff and I were kept waiting in the governor’s outer office for quite some time; we were told that the governor was stuck in traffic coming back from an outside appointment. Ironically, given the way things turned out, while we were waiting there, Lt. Gov. Brian Schatz came rushing in. He said, “Oh, what are you guys doing here?” Surprise!

When we were finally called into Abercrombie’s office, he was not alone. With him were attorney general David Louie, his top political adviser, Marvin Wong, and his chief of staff, Bruce Coppa.

There’s no question the governor knew what we were there for and what the letter would say. Abercrombie’s hands were trembling as he took and read it. The letter put him in a terrible box: If he followed Inouye’s wish, he would be seen as not his own man and would have little by way of gratitude from the new senator. If he disregarded the letter, he would be seen as ignoring the last wish of Hawaii’s most popular and revered politician.

“There’s no question the governor knew what we were there for and what the letter would say. Abercrombie’s hands were trembling as he took and read it.”

Abercrombie said he intended to keep the letter confidential and asked if we would do the same. We immediately agreed, but it didn’t matter: The contents quickly became public through channels in Washington. Jeff and I had nothing to do with its release. This was not the way I anticipated my long friendship with the senator would end.

Once word of the letter got out, there were whispers that Inouye was already dead by the time the letter was produced. That’s not so. In the end, I believe the community turned against Abercrombie over the whole sequence of events. I think that’s why he got killed by David Ige in the 2014 Democratic primary election. The entire Japanese community turned on Neil, it’s very clear. To counter that, in the last part of the campaign, Japanese faces started to appear in all of his ads. Then the haole community deserted him. The environmentalists deserted him. The teachers, too. In the end, there was no hope for Neil.

Yakuza-Infested Waters

First Hawaiian needed to dump a Japanese subsidiary or it would drag down the entire bank

By Walter Dods Jr.

I’ve always been involved with Japan, which is terribly important to the Hawaii economy. However, an earlier First Hawaiian Bank adventure in Japan that happened under my predecessor as CEO, Johnny Bellinger, could have been a disaster for First Hawaiian Bank. It involved the yakuza (Japanese organized crime) as well as two of the richest men in Japan, Kenji Osano and Yasuo Takei. The final chapter of this complex story involved a dinner at a fancy Tokyo restaurant with Bellinger and Osano, a legendary Tokyo investor and developer whose Kyo-ya company still owns many of the major hotels in Waikiki.

In 1978, Bellinger created a banking subsidiary in Tokyo named Japan-Hawaii Finance Kabushiki Kaisha. These consumer finance operations in Japan are called sarakin or “salaryman” companies. (“Salaryman” roughly translates as a white-collar businessman.) In Johnny’s mind, he saw Japanese borrowers – he was thinking of local Japanese people – as thrifty, hardworking folks who paid their bills.

Walter Dods flew to Japan to promote Japanese tourism in Hawaii when it flagged after 9/11. As part of the trip, he met with Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi. Photo: Courtesy of Walter Dods Jr.

These Japanese consumer finance companies were routinely charging 30 to 40 percent on unsecured loans, sometimes even up to 100 percent annual interest. You go there and get a short-term loan – the equivalent of a few hundred dollars at a time. Borrowers would have to pay a really high interest rate but wouldn’t have the loan out for long and then pay it off when they got their bonuses.

Back in the 1970s, many of these companies were connected to the yakuza. Today, they are cleaned up and are respected financial institutions. Many of the survivors are now listed on the Tokyo stock exchange, very well regarded. They are still referred to as sarakin companies, but it’s not the old pejorative term. They’re not yakuza-connected today, but that wasn’t true back when First Hawaiian tried to enter the sarakin business.

Then, Japanese banks were so strong they wouldn’t share customer credit information with us. The heart and soul of being able to make a loan in America is the credit bureaus. Before we lend you money, we can check your credit record. We can find out whether you are a very bad creditor who never pays a bill or maybe you’ve already stuck five other banks. In Japan, they wouldn’t share this information with us.

“At one point, we had exposure in Japan of bad debt equal to the total capital of First Hawaiian Bank.”

We quickly opened a lot of branches, basically storefront operations. Then, the loans started going bad in large numbers. We started taking massive loan losses because less-than-creditworthy customers were coming in, and we couldn’t check their financial information before loaning them money. Back in Honolulu, we were seeing these delinquent credits come in to our weekly management meetings. At one point, we had exposure in Japan of bad debt equal to the total capital of First Hawaiian Bank. It could have done serious damage to the financial ability of First Hawaiian Bank to survive. That’s how serious it had become.

Finally, in the early 1980s, Bellinger decided we needed to get out of the sarakin business. We found a prospective buyer, a company already in the sarakin business called Aichi Corp., run by Yasumichi “Mamushi” Morishita. (In Japan there is a very small, very quick, very venomous snake called mamushi.) Philip Ching at the time was special assistant to Johnny, who asked him to put the deal together. Phil hired Alan Goda, a private attorney in Honolulu with terrific ties in Japan, to represent the bank in negotiating the sale.

Johnny was anxious to complete the deal and get out of Japan. The problem, as it turned out, was that Morishita had a reputation of being connected with the yakuza. Alan Goda was told by his national police connections in Tokyo that this was a very dangerous man. That, plus the way the deal was structured, gave some people pause. (Years later, in 1992, “Mamushi” Morishita’s name came up in a U.S. Senate hearing on Asian organized crime. The chief investigator for the Senate committee testified that Morishita used members of a yakuza group to handle debt collection for Aichi. He added that Morishita owned golf courses in California and Arizona and part of Christie’s Auction House in New York. He had bought $80 million worth of art for his Tokyo gallery, including works by Van Gogh and Picasso. The Senate testimony claimed that at least 50 properties in Hawaii had been bought as fronts for yakuza money laundering, mostly in the mid-1980s.)

“Osano told Bellinger, ‘You have got to get out of this because these are sharks over here and this is not a business for a nice Hawaiian banker to be in.’ ”

One of the biggest potential problems with our potential deal was that Aichi wanted a line of credit from First Hawaiian Bank that was bigger than the bank’s entire net worth at the time, $135 million. It was absolutely clear that, as soon as we signed that guarantee, Morishita would draw down that line of credit. There was no way First Hawaiian could take a loss of that magnitude.

Phil Ching recommended against completing the Aichi deal. But Johnny wouldn’t budge. At one meeting in Johnny’s office, Phil got down on one knee and pleaded with him, “Don’t do the deal with Aichi.” He felt, rightly, that it could have sunk the bank.

At the time, I was president of the bank and Hugh Pingree, the previous president, was vice chairman. The two of us went to Alan Goda’s office and said to him, “You know we can’t allow this deal with Aichi to happen.” Alan decided, on his own, to write a confidential letter to Johnny outlining all the reasons the deal should be called off, including the huge line of credit. Johnny was livid when he got the letter, but, faced with all that opposition, he agreed to pull out of the Aichi deal.

But he still had the problem of how to get rid of our Tokyo subsidiary and all those bad loans. Johnny must have lived under a lucky star. He made friends who really loved him, and one of those friends was Kenji Osano, one of the earliest Japanese investors in Hawaii. In about 1961, his company bought the now-closed Kyo-ya restaurant on the edge of Waikiki. Osano, a bald, rather secretive guy, then picked up the Moana Hotel, the Princess Kaiulani, the Sheraton Waikiki, the Sheraton Maui and the Royal Hawaiian.

Osano took a real liking to Johnny, so they had dinner one night at a Tokyo restaurant. By now, Bellinger realized his Japan subsidiary could have a bad impact on the First Hawaiian franchise in Hawaii.

Osano told Bellinger, “You have got to get out of this because these are sharks over here and this is not a business for a nice Hawaiian banker to be in.” Bellinger was a proud guy, but said, “I could use your help. I’m open to any suggestions.” Osano had a follow-up dinner with Yasuo Takei, head of Takefuji Corp., the largest finance company in Japan. Osano told him, “I’ve been your friend for many years and we’ve done many things together. This guy (Bellinger) is a friend of mine from Hawaii. Take his finance company over, buy it out and merge it in with your operations” – in effect, for a dollar. He took it over, took all the liabilities as a personal favor to Osano. And we got out of that entire episode in 1984 with our skin and our pride intact. If it hadn’t been for that, there could have been massive repercussions on First Hawaiian Bank.

Ironically, years later Takei – who had become Japan’s second-richest man, worth over $5 billion – retired under a cloud himself. He was convicted of ordering the wiretapping of a journalist who had written articles criticizing his company. He apologized and retired before he died.

That was a valuable lesson for me: Know the markets you’re in; don’t do business where you don’t speak the language; make sure you know what you are getting into. I have followed that dictate ever since. That doesn’t mean I don’t go outside of my home market, but, if I do, I need to understand the markets I’m going into and the cultures, the laws, the unofficial customs and rules.

Poaching From “The Enemy”

The tale of two Jacks that shocked Bishop Street

By Walter Dods Jr.

First Hawaiian Bank and Bank of Hawaii face one another across Bishop Street in downtown Honolulu. Because the two of us are such intense competitors, rarely does a top executive of one bank jump across Bishop to the other. On the one occasion it happened during my career, it started with a secret late-night meeting in my garage in Makiki – a clandestine contact that later produced front-page news.

For the most part, we filled top slots in-house. For example, I replaced Johnny Bellinger when he died in 1989 and, when I became CEO, the first thing I did was promote Jack Hoag to be my No. 2 as president. We had a really great partnership and never had a cross word the whole time.

Jack had come to Hawaii as a hell-raising Marine helicopter pilot and a real party guy. There’s a story he tells of himself about showing off his piloting skills for a buddy, a major, one day. He was sliding through the tall grass taking off, and his helicopter hit the stump of a tree and flipped upside down, spinning on its blades. They had a really close call.

When First Hawaiian Bank lured Jack Tsui from Bank of Hawaii to succeed Jack Hoag, this “Jacks” card was part of an invitation to

a changing-of-the-guard event. Photo: Courtesy of Walter Dods Jr.

Jack met his wife in the Islands and stayed here as a bank trainee when he got out of the military. One night when they were quite young, he and Jeanette were driving home on Likelike Highway, and a driver crossed the median strip and hit them head-on, almost killing both of them. They were in the hospital for a long time, and Jeannette to this day has never 100 percent recovered from her injuries.

Jack made a pledge to her that, if they survived, he would convert to her Mormon faith, which he did. During all the time I’ve known him, he was an active Mormon, a good leader and very principled.

Jack is nine years older than I am, so I always figured he would retire first. Even though he was older, he was my succession plan. I was confident that, if I were hit by a bus, he could take over First Hawaiian without missing a beat. My plan was that, before he retired, the two of us would select his successor within the bank and groom him or her. But, in early 1994, he came to see me to tell me his church wanted him to retire early and run the Mormons’ landowning arm in the Islands, Hawaii Reserves Inc. I completely supported him.

So, now what do I do about a successor-in-waiting? I had already identified Don Horner as somebody who could ultimately move up to the top rung. He was still pretty young – 43 at the time – and I had thought I had several years to give Don a lot of other experiences.

“We agreed to meet at my home in Makiki late at night. I put my car out on the street and left the garage door open. He drove into the garage, and I closed the door behind him.”

When Jack suddenly changed that timeline, there was a gap, and I didn’t feel it would be right to move Don up to president right away. First, I wanted to give him the opportunity to handle every increasing responsibility that I knew a mature, seasoned executive should have.

As it turned out, an unorthodox opportunity to solve my successor problem opened up across Bishop Street. Just before Jack sprang his news on me, a four-year internal leadership competition had finally played itself out at Bank of Hawaii. In 1989, the year Johnny died and I took over on our side of Bishop Street, Bank of Hawaii’s CEO, Howard Stephenson, had picked my old friend Larry Johnson to become Bankoh’s president.

That same year, Bankoh also named three new vice chairmen, with the implicit message that one of them would eventually become Johnson’s successor after Larry moved up to the top spot. The three contenders were Jack Tsui, who was in charge of corporate lending; Tom Kappock, head of Bankoh’s retail banking; and Richard Dahl, chief financial officer and youngest of the three contenders.

The trio stayed in place until 1993, when Bank of Hawaii announced that Stephenson would retire and, as expected, be succeeded by Larry Johnson. At the same time, Johnson selected the 42-year-old Dahl to succeed him as president. That left Tsui and Kappock as odd men out at the same time I was looking for a successor to Jack Hoag.

J.W.A. (Doc) Buyers, head of C. Brewer & Co. and a director of First Hawaiian, told me I ought to approach Jack Tsui, whom I had known as a superb banker. He knows more about corporate lending – dealing with major national and international companies – than anyone I’ve known, and I’ve known a lot of prominent bankers.

There had been a tradition for years that Bank of Hawaii didn’t poach executives from First Hawaiian and vice versa. At lower levels, branch managers might have gone back and forth; at senior levels, it was unheard of. Yet I realized that Jack would probably not stay long at Bank of Hawaii after being passed over. I also knew that, with his East Coast background, he was culturally quite different from the typical banker at First Hawaiian. Before I approached him, I weighed whether he could fit in with our culture and came to the conclusion that our culture needed improvement. We were good at certain things with a very good, caring culture, but not as sophisticated as I thought the bank should be in national corporate lending and other major loans. Jack Tsui was very, very strong in these areas.

Doc gave me Jack’s private phone number (I could hardly call his Bank of Hawaii office). I called Jack and said, “This town is really small, and this one is explosive in the community. We can’t talk at a hotel or restaurant or anywhere public.” We agreed to meet at my home in Makiki late at night.

I put my car out on the street and left the garage door open. He drove into the garage, and I closed the door behind him. We went into my study and talked until the wee hours of the next morning – probably five hours or so. We discussed the opportunity to be president of our bank, the culture difference and the internal problems that might ensue from an outsider coming in as president. And, of course, whether we could work with each other.

For me, it was important that Jack Tsui was three years older than I was. I was bringing in an extremely competent banker in an area where we needed some help on wholesale corporate lending, national lending. I’ve never been afraid of bringing in somebody smarter than I am, and that’s how much respect I have for Jack’s banking abilities. Yet, I didn’t feel his hire would be a threat to the future leadership of the bank because, clearly, if my health maintained and I continued to do my job, he wouldn’t be replacing me because of our age differences. The decision would buy time for Tsui and me to groom the next president coming along.

Hiring Jack Tsui was a shock to the business community and it was front-page news in The Honolulu Advertiser. However, I knew the big challenge for me was going to be to manage the internal shock within First Hawaiian. When I told my senior managers, there was absolute shock in the room. We had not gone outside for a major hire since I took over. Also, we and Bank of Hawaii were tough competitors.

The one who surprised me the most was Tony Guerrero, an executive vice president who ran branch operations. I expected him to take it pretty easy, but he was such a competitive guy. He said, “You tell me to go through a wall for you and I will, but now you’re asking me to embrace the enemy.” It was like a sacrilege to him, but he and Jack became good friends.

“(Tony Guerrero) said, ‘You tell me to go through a wall for you and I will, but now you’re asking me to embrace the enemy.’ ”

The move was equally stunning across Bishop Street. The day it was to be announced, Jack Tsui called about 30 people who worked for him directly or indirectly into a conference room at Bank of Hawaii to tell them he had resigned and was becoming president of First Hawaiian Bank. One of those in the room was Bob Fujioka, a senior VP at Bankoh. Bob told me when Jack made his announcement he burst out laughing. He thought Jack was joking.

A year or so after Jack left, Bob (now a First Hawaiian vice chairman) was one of four key bankers who were concerned with Bank of Hawaii’s strategic direction who spoke with Don Horner and eventually moved across the street as well. The others were Bob Harrison (now CEO of First Hawaiian), Lance Mizumoto (president of Central Pacific Bank) and Gabe Lee (executive vice president and top commercial banker at American Savings). The two Bobs – Harrison and Fujioka – were great additions to our First Hawaiian team. I doubt they would have moved if I hadn’t hired Jack. He had mentored them earlier in his career and they wanted to join him. We didn’t actively recruit; they approached us .

Book Signing

Walter Dods Jr. will sign copies of his book Dec. 12 at 11:30 a.m. at the Barnes & Noble store in Ala Moana Center. B&N will donate a portion of sales proceeds during the signing to Aloha United Way; Dods is donating his proceeds from all sales of the book to Aloha United Way.