Kakaako’s Affordable Housing Rarely Is

After all the hullabaloo, the hearings, legislation, planning, permits and protests, the concept of an urban, gentrified Kakaako is now an urban reality in progress. Cranes fill the skyline from one end of Kakaako to the other, with at least five projects underway now, and possibly another couple by the time you read this.

With all this Kakaako development comes a whole new vocabulary: “living up,” for example, generally means the higher the floor, the higher the price; “rec deck” is something akin to a cruise ship’s Lido Deck and, perhaps most controversial and misunderstood, “reserved housing.”

Whether you love reserved housing (like the HCDA, the state agency responsible for its implementation), hate it (like many affordable-housing advocates and free-market developers) or don’t understand it (like most of the rest of us), two things seem certain: reserved housing is a cornerstone of Kakaako and developers are determined to find solutions to meet the reserved-housing requirements they face if they want to build market-priced and luxury condos.

Where that leaves local Hawaii buyers depends on what you want, how much money you have and how savvy you are about the intricacies, terminology and opportunity in this new community.

While it remains true that Kakaako’s shiniest bling might be the front-row luxury condos now under construction along Ala Moana boulevard – the Kakaako now rising up above the stores, cinemas, auto repair shops, furniture importers, et al, will bring housing opportunities of various prices, luxury and design to the market.

“The Hawaii Community Development Authority’s mission is to build community. And communities include everyone,” says Lindsey Doi, HCDA’s compliance assurance and community outreach officer.

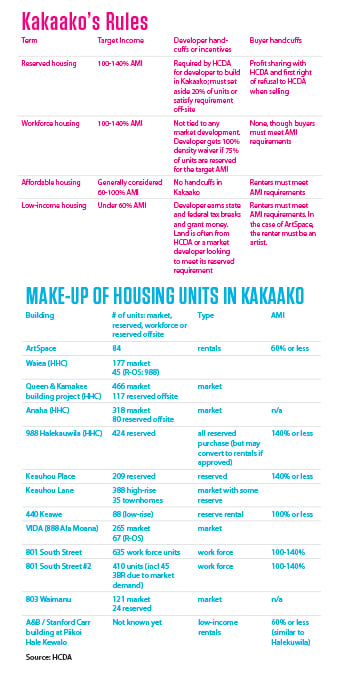

That commitment drives HCDA’s sometimes complicated and often misunderstood reserved-housing requirement. Here’s the deal: The developer of market-priced condominiums in Kakaako must reserve roughly 20 percent of its units for local buyers who earn no more than 140 percent of Honolulu’s adjusted median income (AMI) and intend to make the residence their primary home. This requirement is unique to Kakaako, under the permitting authority of the HCDA, and is not a requirement for other developments in Honolulu. While these reserved units are sometimes labeled “affordable housing,” the reality is different.

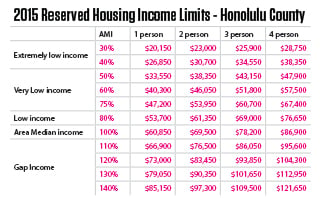

In a community where the price of paradise is steep, who’s likely to be interested in these units? Almost certainly, people you know, work with, volunteer with, see on Sundays at church or on the golf course. Or maybe they are your children or grandchildren, looking to come back to home after college on the mainland. According to the 2015 AMI calculations, a family of four – maybe two professionals with two children – earning no more than $121,650, can qualify for these reserved units. For a single person, the maximum income is $85,150. Not exactly the salary ranges you think of when you hear “affordable housing,” right? (See chart for more examples.)

The first-time buyers of reserved units accept certain handcuffs with their reduced-price homes:

• If the buyer chooses to re-sell the unit within five to 10 years of the original purchase, first right of purchase must be given to HCDA at market rate. The variance of five to 10 years is dependent on the development, so may differ from one building to the next.

• The buyer accepts an equity-sharing agreement whereby the difference between the purchase price (which was likely below market) and the market price when resold is shared equally with HCDA. So if the buyer paid $350,000 for a condo in 2011 when the market value of that unit was $400,000, the $50,000 difference is split equally between the owner and HCDA when the property is sold. Any gain over the original $400,000 market value stays with the owner.

Hard to follow, right? Wait, there’s more. The handcuffs giving the first right of purchase to HCDA end after that five-to-10-year window, while the equity sharing stays with the unit as long as the original buyer owns it. For the second buyer, however, it’s a whole new ballgame. What was once a “reserved unit” is now a market unit – no handcuffs, no restrictions and anybody can buy it.

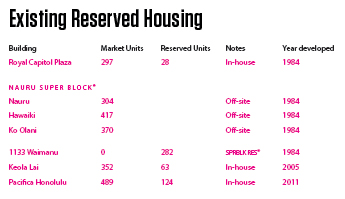

It’s not clear whether this system will work as planned because much of Kakaako’s gentrification is yet to come, but the early players offer some clues. Only a handful of reserved-housing projects have been completed in the quarter century since the requirement was established. Three of those developments included the reserved housing units within the market-priced buildings while the other three (all under one development plan) opted for a separate, purpose-built project on nearby land to satisfy their requirements (see chart below).

In those projects where the reserved units are contained within the building, the units have become an almost indistinguishable part of the market-priced building. In the four years since the completion of Pacifica Honolulu, only 10 percent of its reserved-housing units have resold, all at a solid market gain, even after the equity-sharing split with HCDA. According to Leland Nye, resident manager at the Pacifica, “There’s no in-house distinction between the market and reserved units.”

Oliver McMillan, the development company responsible for Pacifica and now building the Symphony Honolulu project across from the Blaisdell Center, says the reserved units in those projects are a great deal. “The program offers an exceptional opportunity for first-time homebuyers, young professionals and others who qualify and who desire to live in an ideally located, sustainably designed urban icon such as Symphony Honolulu,” Dan Nishikawa of Oliver McMillan says .

Others disagree. The monthly management fee for these market buildings can be steep. Even if a family can pull together the down payment and financing for a unit, do they want to take on the monthly maintenance fee, too? Projects now under construction cite fees in the ballpark of $1.14 per square foot; for a 1,000-square-foot condo that’s an additional $1,114 a month for the benefit of a pool, fitness center, movie theatre and other common elements.

“Some buyers just can’t pay those additional fees,” says Doi, suggesting that the separate, purpose-built projects offer those buyers more modest options – fewer amenities and lower fees.

That’s the theory behind the 988 Halekauwila project, Howard Hughes’ proposed solution to meet its reserved-housing requirements for its front-row luxury buildings. A purpose-built reserved-housing project proposed for the corner of Halekauwila and Ward, 988 Halekauwila is touted as a modern, modest building designed for local, working families. The project is currently permitted as units for purchase, meaning they will be available to those earning no more than 140 percent of AMI. However, Howard Hughes is petitioning HCDA to amend its permit to turn the building’s units into affordable rentals, which would be rented to those earning no more than 100 percent AMI. Similar projects are on the drawing board at the other end of Kakaako, on Kamehameha Schools land, where Castle & Cook is building 440 Keawe, a reserved-housing project of rental units targeting local families earning no more than 100 percent of AMI.

Kakaako’s reserved-housing requirements do not hinge on any government subsidies or tax breaks, but are strictly a permitting requirement to get HCDA approval. Opponents of the requirements argue that they are cumbersome and counterproductive.

“We need more housing, not less,” says Paul Brewbaker, local economist and housing advocate. “The literature in housing economics clearly shows that quotas are not just ineffective. They are counterproductive.”

“Building a neighborhood is complicated,” says Makani Maeva, a long-time affordable-housing advocate and developer in Hawaii, “and it isn’t a neighborhood unless you have people really living there.”

While many Kakaako insiders believe that reserved housing is doing little to create truly “affordable housing” – generally thought of as housing serving people falling under 60 percent AMI – Maeva sees small glimmers of hope.

“Halekauwila Place works,” she says of Stanford Carr Development’s recently opened low-income rental project, offering modern studios to three-bedroom units, for those falling under 60 percent AMI. Likewise, she is hopeful about Stanford Carr’s new venture on Alexander & Baldwin land. A&B decided to outsource its reserved housing requirements for the recently opened luxury project Waihonua: A&B is providing the land and Stanford Carr will build and develop the project, tentatively called Hale Kewalo, following the Halekauwila Place template.

“I’ve also heard really good things about Artspace Lofts,” Maeva says about the recently approved project on Waimanu Street targeting low-income artists, scheduled to be completed by early 2017. “Those hardest to serve,” she says, “are those falling between 60 and 100 percent AMI. There’s no financing and no inventory.” With Halekuwila Place already filled, and no other projects completed yet, the few on the drawing board – such as Stanford Carr’s A&B project and Artspace – are desperately needed and anticipated.

Jack Tyrell, a local real estate broker who’s long been bullish on urban development in Kakaako, thinks HCDA’s reserved-housing concept misses the mark.

Jack Tyrell, a local real estate broker who’s long been bullish on urban development in Kakaako, thinks HCDA’s reserved-housing concept misses the mark.

“You’ve got 100 people or so making $50,000 to $150,000 in profits when they resell reserved units and that’s all you’ve done,” he said. “That doesn’t help the community over the long haul.”

Like most market observers, Tyrell believes the answer lies, in part, in more affordable rentals, and not just in Kakaako. “Affordable rentals serve the community. Build rentals next to rail,” he suggests, “and build modest buildings that working families can afford.”

As for HCDA, Tyrell sums it up this way. “Without HCDA, we wouldn’t have this community, so as someone who lives here, I’m glad they’re there, doing their job.”

Want to Live in Kakaako?

Here’s what you need to know if you want to buy a condo or find a rental:

• Reserved housing units in market-priced buildings go quickly. If you want the amenities of a market building (pool, fitness center, movie theatre and other luxuries), and can afford the monthly maintenance fees, do your homework and show up when the units go on sale. Reserve units are sold through either lottery or on a first-come, first-served basis. Like all new condo purchases, your up-front cash is reasonably modest, with the big payment due when the building is complete. Make sure to understand the fine print and the legal restrictions.

• Reserved units up for resale in market buildings can offer great value. Those units are often priced competitively, particularly for the first resale, and their quality is on par with all the market units in the building. There aren’t a lot of them, however, so it pays to know the buildings and the offerings, and when one hits the market, move fast. Currently, the only buildings with reserved units that might go up for re-sale are Keola Lai, Pacifica and Royal Capitol Place. In a few years, look out for Symphony units to hit the resale market.

• Want to buy a place, but don’t want the big fees and all the amenities? Consider the purpose-built reserved-housing buildings like 1133 Waimanu, which has been a contender in Kakaako since 1985. If you’re looking for something newer, watch the Howard Hughes and Kamehameha developments. Their purpose-built projects are still on the drawing board, but be first in line when they open for sales.

A similar project, but developed under different rules, the 801 South Street project is another one worth following. Called “workforce housing,” this project is a stand-alone development not tied to any market or luxury building, and is designed for working families falling in the 100 to 140 percent AMI range. While both towers are now sold out, look for resale units to hit the market.

The flip side to these purpose-built buildings, say some market experts, is that they will always carry a stigma of “workforce” or “affordable,” thus perhaps dampening appreciation. Others argue that they serve a growing niche and will appreciate accordingly.

• Hoping to score a rental? Good luck.

Hawaii needs affordable rentals, but few get built. Here’s where you’ll want to do your hunting:

• Halekauwila Place is open and 100 percent occupied, but taking applications for its waiting list.

• Six Eighty, part of Kamehameha School’s OurKakaako project, has one studio unit available at press time (350 square feet, at $1,150 a month), but they also have a lengthy waiting list.

• Rycroft Terrace, formerly part of the Pagoda Hotel, is being converted to rentals as part of Alexander & Baldwin’s reserved-housing conditions for The Collection project.

• Hale Kewalo is scheduled to be completed in the next couple of years, targeting households under 60 percent AMI.

• Howard Hughes is seeking HCDA approval to make its 988 Halekauwila Place a rental project, which would then be completed within the next couple of years.

• Don’t forget to check the market buildings for rentals as well. Waihonua, Pacifica, Moana Pacific and 909 Kapiolani often have units offered as rentals, but, like all the others, they go quickly.

Kakaako’s Housing

Total housing units already in Kakaako: 7,143

Total reserved units already built: 497

Workforce units already built: 635

Market price units: 4,610

Dedicated Rentals: 1,401

Source: HCDA

Note: The number of reserved units does not equal 20 percent of the market units because several projects were exempted from the reserve requirements over the years, especially during weak real estate markets.