Kakaako: Remade for the 21st Century

An Economist Makes (Dollars and) Sense of It All

By Powell Berger

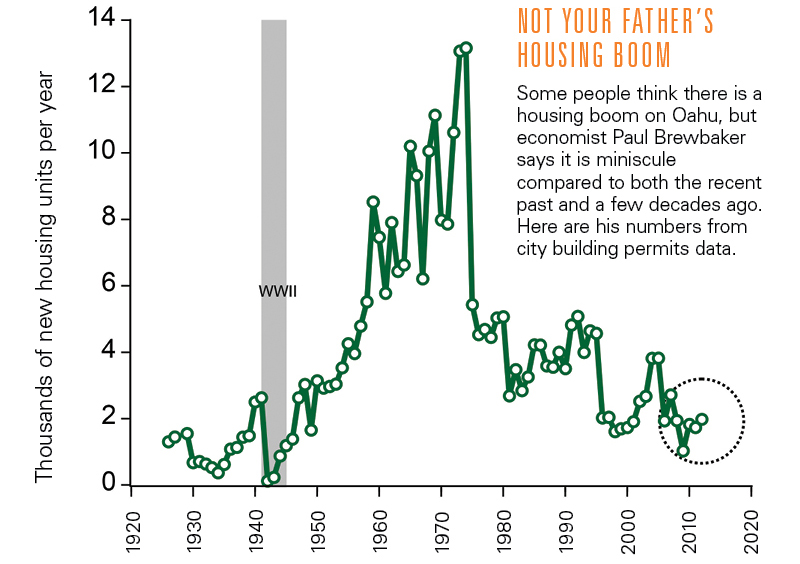

SOME may label the construction activity in Kakaako “condo-mania,” as the Honolulu Star-Advertiser did, but local economist Paul Brewbaker says the opposite is true.

“The only time we permitted fewer new housing units on Oahu was during World War II,” he points out. “There are barely a dozen cranes along the Honolulu skyline,” he says, and a third of those are at Ala Moana Center. “Twenty or 30 cranes, now that’s development!”

To understand him, look at the chart. Drawing on historical data, Brewbaker’s chart shows the housing units authorized annually by city building permits. Those numbers suggest that new housing on Oahu remains near historic lows – not even keeping up with the increase in population.

Brewbaker’s bullishness about the new Kakaako has a lot to do with his developer clients, but those who know him quickly point out that he always speaks his mind, regardless of clients and corporate interests. The economist says four distinct factors come together in a “perfect storm” that supports the transformation of Kakaako:

> The continued rise of the service-sector economy in the 21st century, across Hawaii, America and around the world;

> The power of agglomeration, with dense clusters of people living and working in the same area, thus creating more opportunity for synergy and collaborative creativity.

> An aging population that creates a distinctly different 21st century demographic; and

> A need for housing on Oahu, as evidenced by housing prices that are among the highest in the nation.

Brewbaker maintains that the urban core of Honolulu will drive much of the entire state’s economic growth in the first half of the 21st century, and that much of that growth will hinge on the continued expansion of the state’s service sector. While sometimes belittled as low-wage/low-impact jobs, today’s service sector bears little resemblance to its mid-20th-century counterpart. The service sector now includes plenty of middle-class and executive-level jobs in finance, information, healthcare, technology, real estate and personal services, and is one of the most robust elements of the 21st century U.S. economy.

“I drove a forklift at Dole Cannery,” he says. “That world is over. Today’s world is one in which we produce services and information and have fresh strawberries at Safeway every day of the year.”

Reports from the Urban Land Institute and other researchers underscore the idea that 21st-century living is more urban, with cities around the country creating vertical communities for housing needs and community vibe. “The living-in-the-suburbs-and-working-in-the-city model is gone or dying in every city on the planet,” Brewbaker says. Honolulu’s crushing traffic, high gas prices and parking woes all enhance the appeal of Kakaako’s live/work/play model.

The island’s changing demographics also play a role. In the mid-20th century, population pyramid was fat on the bottom with lots of children and pointed on top with a few elderly people. Today, the pyramid is more like a square, with age groups of relatively equal size. The number of people 65 and older in Hawaii is now almost equal the number of school-age children.

“These people weren’t here before. They didn’t live that long,” Brewbaker says. National and local research suggests this aging population finds urban living attractive, with culture, community and health care close to their front doors.

Last, and perhaps most critical, Oahu’s housing shortage is crippling. Smaller households and a growing population leaves Brewbaker forecasting the island needs to add 3,500 housing units a year just to keep up with demand.

“In the 25 years from the end of World War II to 1974, we built an average of 8,000 housing units per year on Oahu. We haven’t built 2,000 per year in the last five years,” he explains.

Brewbaker says the mobility of capital in the 21st century further complicates the equation. “Even if nothing happens, 50 guys from California come to Hawaii to buy condos,” he says. By diversifying the available housing, especially the ultra-luxury units being built in Kakaako, the rest of the inventory is left for local residents.

What if the developers can’t sell all the high-end units being built? Brewbaker says that’s their problem. They take the risk and reap the reward if it succeeds. “If they fail, local residents have a shot at multimillion-dollar units at a fraction of the price.”

As for the opposition to the Kakaako development, he doesn’t pull his punches. His caustic take on the NIMBY opposition is: “Keep the country country, but don’t make the city city.” His view: Modern urban planning is more conducive to green space than its 20th-century counterparts.

He’s also incredulous that much of the opposition to development in Kakaako comes from existing residents of Kakaako towers. He mocks that opposition as “Don’t build a high-rise next to my high-rise.”