Is Hawaiian Telcom’s IPTV Rollout a Game Changer?

PHOTOS BY RAE HUO

It’s hard to avoid baseball metaphors when talking about Hawaiian Telcom.

Five years ago, faced with three straight quarters of losses, crippling debt and imminent bankruptcy, the century-old local telephone monopoly appeared to be down a couple of runs, with two outs in the bottom of the ninth. Worse still, the company seemed outmanned by the competition. Oceanic Time Warner Cable, the big-league team from the mainland, simply had too deep a bench. Inning after inning, while Hawaiian Telcom hemorrhaged its traditional residential landline customers, Oceanic steadily pounded out a larger and larger market share with its virtual monopoly on cable TV, at the same time collecting plenty of landline and broadband customers, too.

Hawaiian Telcom appeared doomed. Then, improbably, the phone company started hitting singles.

First, bankruptcy put Hawaiian Telcom on a sounder financial footing. With its debt reduced, the company has enjoyed 11 successive quarters of profitability. More important, the old-fashioned phone company has been investing lavishly on modernizing its infrastructure, which means it can offer new services. The most important of these is Internet-protocol TV (IPTV), a technology that leapfrogs traditional cable-TV technology and gives Hawaiian Telcom a chance in its battle with Oceanic.

The game is by no means over. Oceanic is busily investing in its own network and we wish we could tell you more about that, but Oceanic elected not to be interviewed for this story. And there are more than just two teams in this league: Netflix, Amazon, Hulu and others are persuading many people to give up on traditional ways of watching TV, though they are all still dependent on broadband Internet to reach customers at home.

Who will win the struggle between Oceanic and Hawaiian Telcom? That may depend on – to use one last baseball metaphor – who can pull off the industry’s double or triple play most often: convincing customers to sign up for not just one service, but for landline phone, high-speed Internet and TV. According to executives at Hawaiian Telcom, IPTV is the key to its triple play.

What IPTV Means

Technologically, what makes IPTV different is the IP part. Instead of using radio-frequency-based signals, IPTV relies exclusively on the zeros and ones of the digital age. In this sense, TV is just one more component of broadband – no different from voice or high-speed Internet. Among other advantages for IPTV, it is device agnostic. For example, it allows you to watch television content as easily on a tablet or a smartphone as on a television set.

“This IP-based TV platform really fully enables our capabilities,” says Eric Yeaman, CEO of Hawaiian Telcom. “We have the ability to provide mobility, so there are TV-everywhere applications. We also have Twitter on TV, and we can take popular apps that are out there and embed them into our platform and really expand its capability compared to the platform of our competitor.”

A good example of IPTV’s versatility is its multiroom DVR capability. Customers can start watching a program in one room, then transfer the program to another device or another room when they want to change locations. That’s a feature that cable providers like Oceanic have resisted because it doesn’t fit their revenue model.

Multiroom DVR is just one way that IPTV creates a better television experience, says Hawaiian Telcom COO Scott Barber. “With IPTV, you also get instant channel-change time,” he says, rather than the lag time of changing channels with a cable remote. “Instead of trying to send 300 channels to the home all at once and have a tuner and a set-top box try to find the channel you’re tuning to, which is what a traditional cable system would do, we just send the channel that you’re requesting with your remote to your TV set.” Also, being a native Internet speaker means IPTV is ideal for high-definition television.

But the main advantage of IPTV is how it changes the business model. It allows telcos like Hawaiian Telcom to finally offer the same kind of bundling options as their cable competitors. “Prior to launching TV,” says Yeaman, “it was very difficult for us to compete with Oceanic, because they had the triple-play: TV, plus Internet, plus home-phone services. Now, IPTV has allowed us to increase our capture rate on the Internet side. Nine times out of 10, when a customer buys our TV, they take our Internet service, if they don’t already have it. It also improves our retention rate on home-phone services. As a result of all this, our residential business is now growing month over month, quarter over quarter, year over year. Whereas, before IPTV, it was a declining revenue business.”

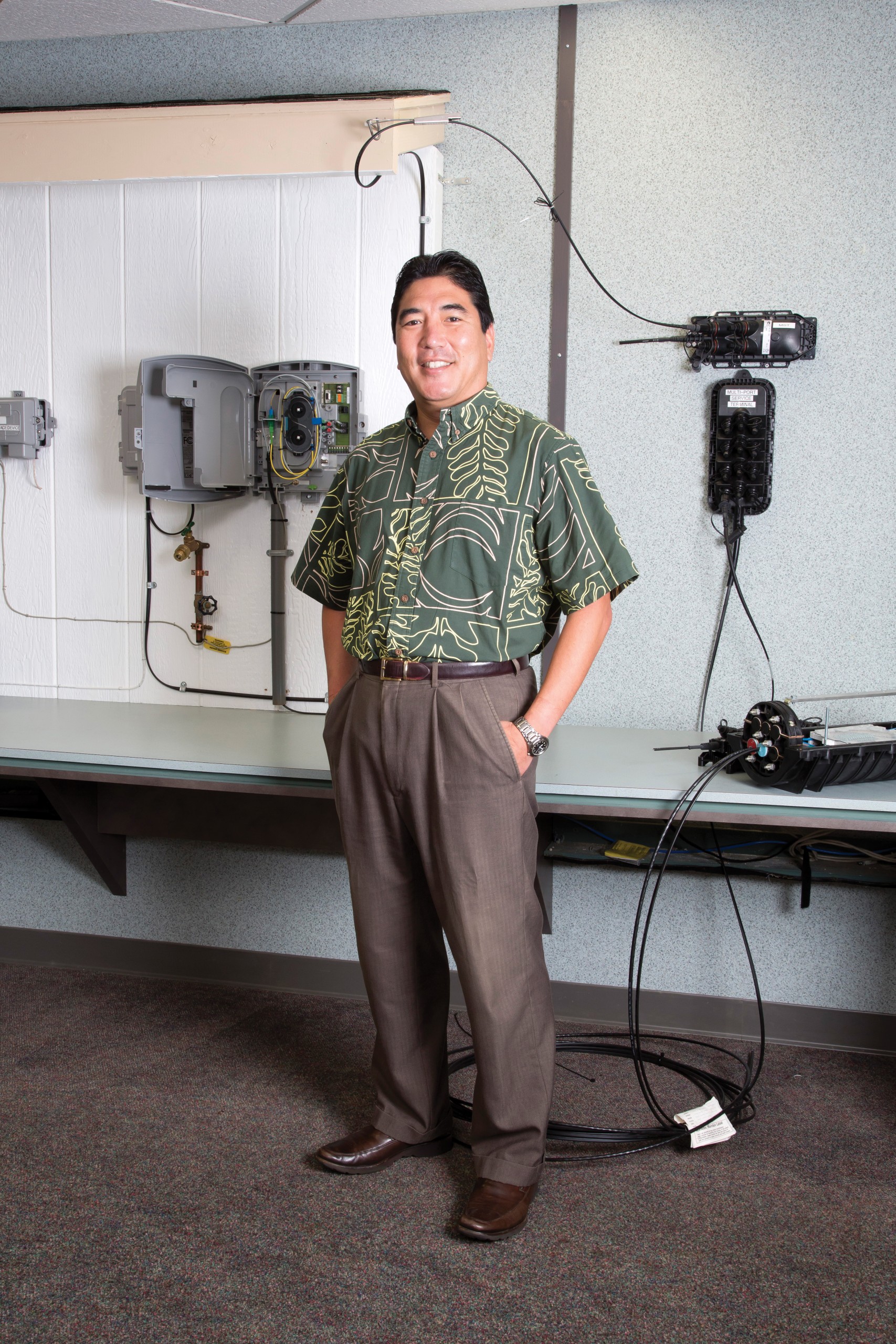

CEO Eric Yeaman, right, and COO Scott Barber stand in the demonstration room at Hawaiian Telcom’s Bishop Street headquarters, where consumers can test drive IPTV.

Mainland examples

Hawaiian Telcom’s experience parallels that of major telcos such as AT&T and Verizon, who have had their own battles with cable giants such as Time Warner, Comcast and Cox. According to Ford Cavallari, a telecom consultant with Portmeiron Ltd., in the 1990s, average revenue per user for the telcos had declined from about $150 per month to about $40 or $50. By the early 2000s, though, companies that were able to add mobile phone service for their customers could increase average revenue per user to around $100 a month, Cavallari says. “And, if you’re also selling a television product with some premium subscriptions, like HBO or Showtime, you can push ARPU back to the $150 to $160 level of the last decade.”

More important, by including IPTV in their bundles, the telcos have been able to take market share from the cable providers. Cavallari uses the example of U-Verse, AT&T’s IPTV offering (and the model for Hawaiian Telcom’s system). “They were able to get a 30 percent to 40 percent share in the space of just three years,” he says. “And, over those three years, their average net add of subscribers – people who signed up for U-Verse – has been 210,000 a month. With Comcast, on the other hand, those numbers have basically been flat.”

Indeed, over the past 11 quarters, the nation’s cable providers have been steadily losing market share to IPTV providers like U-Verse and Verizon’s FIOS system. (On the mainland, satellite providers have also been stealing market share from the cable companies, but local geography makes them less competitive in Hawaii. Also, satellite doesn’t provide the broadband and landline add-ons.) According to an August report by IHS, a leading market analyst firm, cable companies lost 598,000 customers nationwide in the second quarter of 2013 alone, while U-Verse and FIOS added 398,000 customers.

So it’s not surprising that IPTV has improved revenue for the major telcos, as Gordon Brown, AT&T’s executive director for market development, explains in an email: “We’re thrilled with U-Verse’s growth. As of the second quarter of 2013, U-Verse is a nearly $12 billion annualized revenue stream and represents more than 50 percent of AT&T consumer revenues. That’s impressive, especially when you consider that, two years ago, U-Verse accounted for less than one-third of consumer revenues.” He adds that AT&T plans to expand U-Verse by about 8.5 million customer locations over the next two years, bringing IPTV to more than 33 million locations. AT&T has clearly decided IPTV is good for revenue.

In addition, IPTV has helped to slow the telcos’ systemic churn of customers, which, according to Cavallari, can hit 10 percent per quarter for younger demographics. “Older demographics are less likely to churn,” he says, “but they’ll still be around 6 percent to 7 percent, even on what are traditionally the most solid customers. But that’s if customers only take one product. The interesting thing is, if you add a second or a third product, you can get churn levels far below that. Certainly, you can get them to 1 percent per month or maybe 3 percent per quarter. With the triple play, customers don’t churn.” This is why bundling is so important to telcos such as AT&T.

It’s important for Hawaiian Telcom, too. “When I joined this company in 2008,” says Eric Yeaman, “I think we were losing 11 percent of our residential land lines a year. We’re now below 5 percent a year, and are probably one of the best in the country as it relates to line losses. We’re still declining, though. I think last quarter it was just under 5 percent. On the business side, it’s flat; on the consumer side, it’s probably 8 percent.”

Slowing this decline is important, because landline service is still profitable and a major component of the company’s revenue. “We have what we call ‘local and long-distance revenue,’ ” Yeaman says. “That’s about 43 percent of our revenue. Then, we have what we call ‘network-access revenue,’ which comes from wholesale and business customers. That’s about 33 percent of our revenue. Consumer high-speed Internet is about 10 percent; video is still only about 2 percent; and the remaining is ‘other.’ ”

Clearly, if you just look at revenue, Hawaiian Telcom is still very much a phone company, but you get a different picture when you look at capital expenditures.

Fiber Optic

Although IPTV may be critical to Hawaiian Telcom’s short-term success, the real key to the company’s future is building the fiber-optic network that enables this technology. For a century, phone companies like Hawaiian Telcom have relied on a system that uses electrical signals transmitted over copper wire. That’s how most phones work even today, and it’s still how many of us reach the Internet – however intermittently.

Even the co-axial cable used by the cable companies is just another version of copper. Whatever its failings, copper has been a surprisingly resilient technology, and it continues to get better. By finessing the old technology with innovations like time-division multiplex networks, it’s possible to achieve speeds of more than 100 Mbps using the old copper infrastructure. That’s a lot of bandwidth. Nevertheless, the end is in sight.

According to most experts, the future is fiber-optic cable, which replaces electrical signals over copper wire with pulses of light transmitted over glass fibers. As Daniel Masutomi, Hawaian Telcom’s director of emerging technologies and integration, points out, fiber has many advantages over copper.

Daniel Masutomi, director of emerging technologies, is leading Hawaiian Telcom’s transition to fiber optic.

“You’re not bandwidth constrained,” he says, “and you never will be. There’s also a lower operating cost to manage a fiber network compared to a copper network, because there’s a lot of grooming involved to get high bandwidth over copper. Interference can occur on a copper network that won’t occur on a fiber network, so there’s a lot less maintenance involved on a fiber network.” Most important, because light can be transmitted on an infinite number of wavelengths, the bandwidth for fiber optic is theoretically limitless.

But, as Hawaiian Telcom has discovered, building a fiber-optic network isn’t cheap. “We’ve invested $80 million a year over the five years that I’ve been here,” says Yeaman. “That’s $400 million that’s gone into our network and the systems to support the growth of the business; $80 million is about 20 percent of our annual revenue. Most of the companies in our space – the companies that we compare ourselves to – have only been spending 13 percent to 14 percent of their revenue. Of course, we won’t be spending 20 percent forever, but we believe we need to invest today to grow the business for tomorrow, and our investors have been supportive of that.”

But the build-out is far from done. To begin with, Hawaiian Telcom’s 15-year franchise for IPTV service only covers Oahu. Even on Oahu, which has about 300,000 homes, building the fiber network is going to take time. “Our goal,” says Yeaman, “was to build out about 80 percent of those homes over a five-year period, starting in July 2011.”

As a practical matter, “build-out” means providing customers with the bandwidth to accommodate IPTV. Ideally, that would entail ‘fiber-to-the-premises’ or ‘fiber-to-the-home’ (FTTH), the industry holy grail. With FTTH, content will flow from content providers, through Hawaiian Telcom’s network, directly into your home, all on a fiber-optic cable. We’re still a ways off from that ideal, though. For now, most customers have to settle for fiber-to-the-node technology (FTTN), which brings the fiber-optic cable into your neighborhood, but uses copper for the so-called “last mile” to the home. That will gradually change.

“But right now,” Yeaman says, “most of that new infrastructure is fiber to the home. We’ve enabled 50,000 homes per year in our first two years, and we continue to stay on track with that goal. Our plan was, as we built out, to get to at least 30 to 35 percent penetration into that footprint of homes. As of our last reported numbers, which was June 30, 2013, exactly two years from when we launched, we had a little over 100,000 homes enabled, and we had just under 14,000 TV customers, so about a 14 percent penetration.”

These numbers are actually even better than they appear. Oahu may have 300,000 households, but many of them are on military property and may have contracts with other providers. Similarly, many condos and apartment buildings have exclusive contracts with Oceanic, and so are inaccessible to Hawaiian Telcom for the next three or four years. Along the same lines, Sandwich Isles has the exclusive license for Hawaiian Homelands, which precludes Hawaiian Telcom from building there. Nevertheless, the company expects to have built out 240,000 to 250,000 households by the middle of 2016.

More than IPTV

Fourteen percent penetration might seem low, but, as Yeaman points out, all that TV revenue is incremental income. “You know, in this business, if you can grow your top line by 1 percent, you’re a hero, because most companies in our space are shrinking. So, TV alone is a $1 million a month business for us and growing. It does and has provided us growth on the consumer side of our business. Every month, there’s growth. Therefore, every quarter, there’s growth. And now, year over year, there’s growth.”

Yeaman also notes that while TV may be a lower-margin business, it’s the key to increasing Internet service and phone service, which have higher margins. “TV, right now, is about break-even as a stand-alone business, but because is allows you to pull through Internet and home phone, it ultimately is hopefully letting you not only grow your revenue, but improve profitability.”

It’s also worth remembering that IPTV is just one component of Hawaiian Telcom’s growth, representing just 2 percent of revenue for now. In fact, residential services as a whole only represent about a third of the company’s revenues. Business services account for a whopping 43 percent, and wholesale – Hawaiian Telcom selling network access to wireless providers and other long-distance providers – accounts for another 20 percent. “In fact,” Yeaman says, “wholesale is our most profitable segment.”

As Hawaiian Telcom becomes more of a technology company and less of a plain phone company, the services it offers are expanding. Over the last two years, for example, the company has increased its footprint in the data-center and cloud-computing segments by acquiring two companies, Wavecom Solutions and SystemMetrics. Before that, Hawaiian Telcom served this market by partnering with D.R. Fortress, but a recent market study persuaded the company to jump into cloud computing with both feet.

“In that study,” Yeaman says, “our consultant, who’s also done this in other markets, estimated that, on the conservative side, cloud computing and co-locating is going to be about a $100 million (a year) revenue business in Hawaii, and that it could potentially be as big as $150 million. He also estimated that it was only about 6 percent to 7 percent penetrated. We think that’s a land-grab opportunity, and the faster we can get to market, the faster we could start to take advantage of that opportunity.” So, rather than build its own networks, Hawaiian Telcom acquired them, something unimaginable two years ago when it was in bankruptcy.

There are still challenges ahead. For one thing, it’s possible to grow too fast. “We have to balance building out our new infrastructure and dealing with our legacy network,” says Daniel Masutomi. After all, copper is going to be around for quite a while; it’s going to need ongoing maintenance and even upgrading. The company also has to manage expectations. For customers in some old buildings that can’t be retrofitted for fiber, or rural customers (like this writer living in Kaaawa) who have inconsistent or substandard Internet service, fiber build-out elsewhere is no consolation. Hawaiian Telcom will have to be careful not to over-market IPTV so they don’t disappoint these customers.

Finally, there’s a real change in the mindset required when you go from being a monopoly providing phone service to a captive audience, to trying to sell technical services in competitive segments like cloud computing or pay TV. In fact, that was part of the calculus in buying Wavecom and SystemMetrics. “One of the reasons we’re keeping SystemMetrics separate,” Yeaman says, “is because we want them to continue to be an entrepreneurial, nimble company. And we want our company here to learn from them how to be more nimble and assertive.”

That’s definitely a different approach for an old phone company like Hawaiian Telcom. And with Oceanic making many of the same investments, maybe we can get away with saying, “It’s a whole new ball game.”